Spain’s long-term care system at a crossroads: Demographic pressures and workforce challenges

Spain’s long-term care system faces a dual transformation – rapid population ageing and a shift toward personalized, deinstitutionalized care. Meeting these challenges will require doubling the workforce by 2030 and addressing precarious labor conditions.

Abstract: Spain’s long-term care system, one of the cornerstones of its welfare state, is under mounting strain from demographic and institutional pressures. Official projections point to the population over 65 increasing by 1.4 million by 2030, raising demand for care benefits by 27%, with more than 2 million people officially recognised as dependent. Home-based care is projected to represent one-third of benefits by 2030, but this requires a doubling of the workforce to 572,200 full-time equivalents. Yet, the sector continues to struggle with low wages (about €10,000 below the national average), high turnover, and unstable temporary contracts which affect one in four workers. Women make up the vast majority of the workforce, and more than half of employees are over 45, compounding the difficulties of recruitment and retention. Without improvements in working conditions and greater investment, Spain risks a shortfall in the care-related workforce needed to ensure dignity and equity for its ageing population. Ultimately, transforming the system will demand stronger political commitment and significant new funding to keep pace with social needs.

Introduction

The System for Autonomy and Care for Dependency (SAAD, for its acronym in Spanish) is one of cornerstones of the country’s welfare state as it enshrines the right to receive long-term care (LTC) in the event of dependency. Since it was established in 2006, it has been evolving into a more inclusive social protection model, although important challenges, including coverage gaps, regional equity and economic sustainability still require action.

Today, the system faces at least two far-reaching structural challenges: the first is demographic in nature, related with population ageing; the second is institutional, derived from the deep transformation of the model towards deinstitutionalised and personalised dependent care.

Demographic pressures on long-term care demand

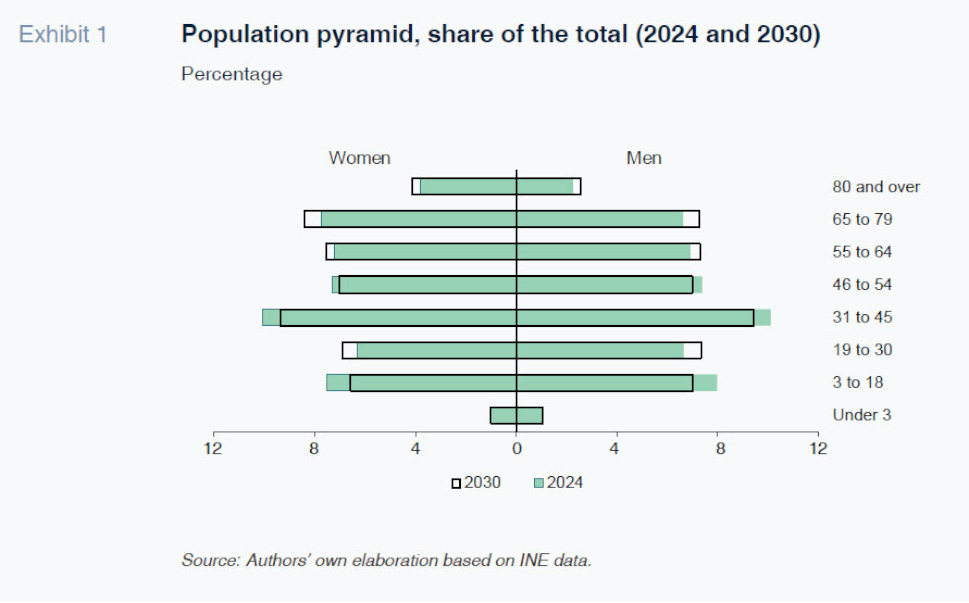

Firstly, the sustained increase in life expectancy and ageing of a particularly populous generation is driving up the number of older people demanding long-term care both in terms of scale and intensity. According to the latest projections from the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE, for its acronym in Spanish), in just five years (2025-2030), the Spanish population over the age of 65 will increase by 1.4 million people, surpassing 11.6 million. As a result, the percentage of people over the age of 65 will reach 22.4% of the total, almost 2 percentage points more from where it is today.

In the medium and long term, the growing share of elderly people will be even more pronounced in the over-80 cohort, which is precisely the group that needs more intense care and support. By 2050, in fact, 10.8% of the Spanish population is expected to fall within this category (5.9 million people), which is nearly double the share observed in 2024 (almost 3 million people more).

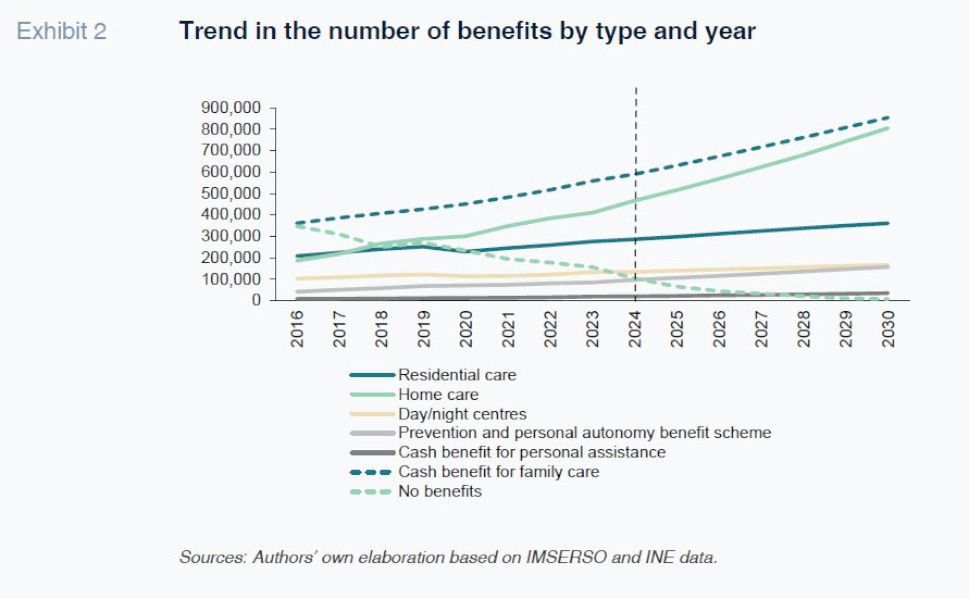

The direct consequence of the country’s growing elderly population is a substantial increase in demand for personal care and support. Our estimates, based on microdata from the Institute for the Elderly and Social Services (IMSERSO, for its acronym in Spanish) and INE’s population projections, [1] suggest that, if the current trend in dependent care system coverage continues, the number of people officially recognised as dependent, and therefore entitled to benefits, will exceed 2 million by 2030, a 27% increase from year-end 2024. That would mean that 13.2% of the population over the age of 65 would be receiving some form of benefits under the dependent care system, which would be equivalent to 4% of the total Spanish population, compared to 10.6% and 2.9% in 2023, respectively.

This scenario, in which it is assumed that the current trends continue, including the trend observed in the benefits mix since 2016, also indicates that the share of institutional care will fall as a percentage of the total, to be increasingly replaced by home-based care, which would account for nearly 34% of the total in 2030. In total, more than 2 million dependent individuals would receive 2.3 million benefits by the end of the decade (excluding teleassistance, due to its complementary nature), considering both financial benefits and social services.

Workforce requirements and labour costs

Considering these projections, which only factor in demographic dynamics and prevailing trends in dependent care benefits, the system would need to employ around 572,200 full-time equivalents, focusing exclusively on first- and second-level care in day and night centres, residential facilities, and home care, doubling the figure observed in 2023 using the same estimation methodology. [2] An important caveat to be taken into consideration when interpreting our estimates is that they depend largely on the ratio of workers per dependent individual considered for residential and at-home care, [3] which varies considerably by region in Spain.

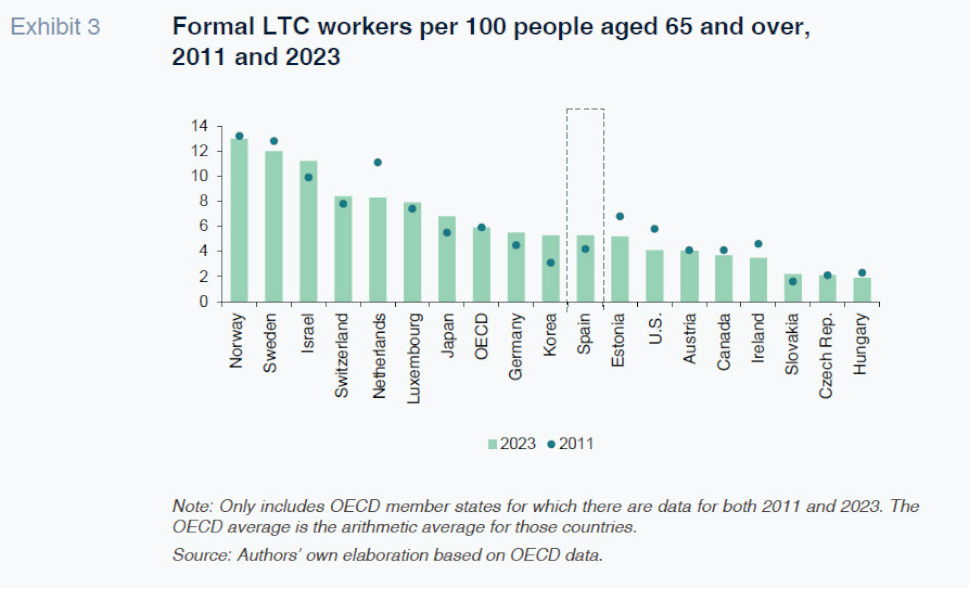

Assuming this scenario, the total labour cost associated with the projected number of workers would increase from 0.4% of GDP in 2023 to 0.7% in 2030, [4] so that the sectoral wage bill would clearly grow more than nominal GDP. Although these figures would exert further pressure on the system, it is worth noting that in 2021, Spain allocated 1% of its GDP to long-term care services, which is well below the OECD average (1.8%) and significantly below levels observed in the Netherlands (4.4%), Norway (2.5%) or Sweden (2.4%) (OECD, 2023).

As for the institutional transformation, the State Strategy for a New Community Care Model (2024-2030) contemplates a structural change in the dependent care system towards a deinstitutionalised and personalised care system by the end of the decade. However, Spain is far from the care coverage standards needed to implement a change of this magnitude: the ratio of long-term care workers per 100 inhabitants over the age of 65 is below the OECD average and significantly lower than the coverage provided in countries like Norway and Sweden, which pioneered this personalised model. The shortfall is not only the result of a smaller volume of human resources and workforce associated to the sector, but also to wage differentials and working conditions that show significant room for improvement and thus retention.

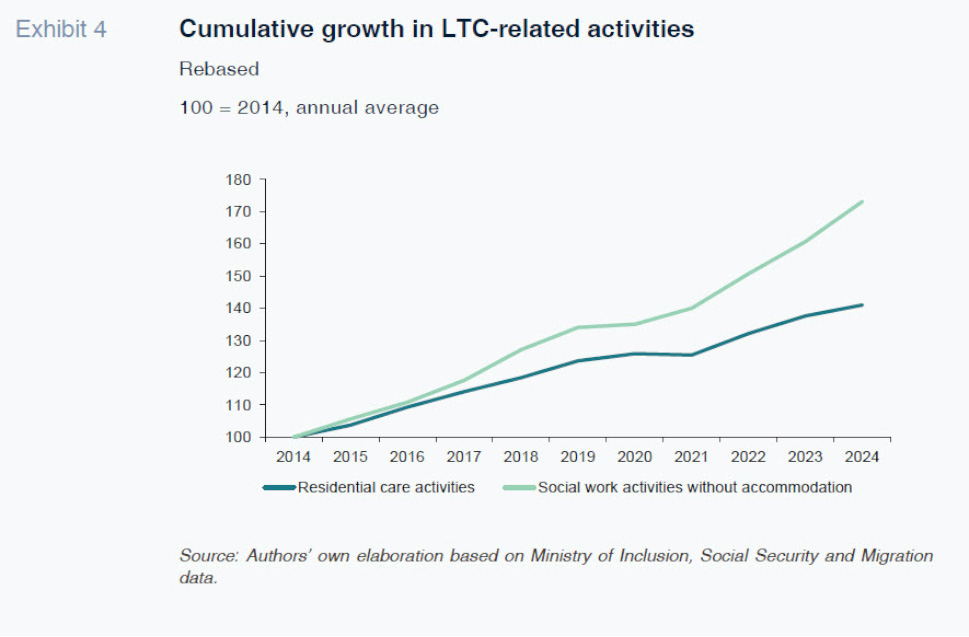

Accordingly, both population ageing and institutional changes require bringing a significant volume of stable and professional human capital into the Spanish care system over the coming decades. A process that is already underway, as employment in the sector has grown substantially in recent years, especially in the direct care segments.

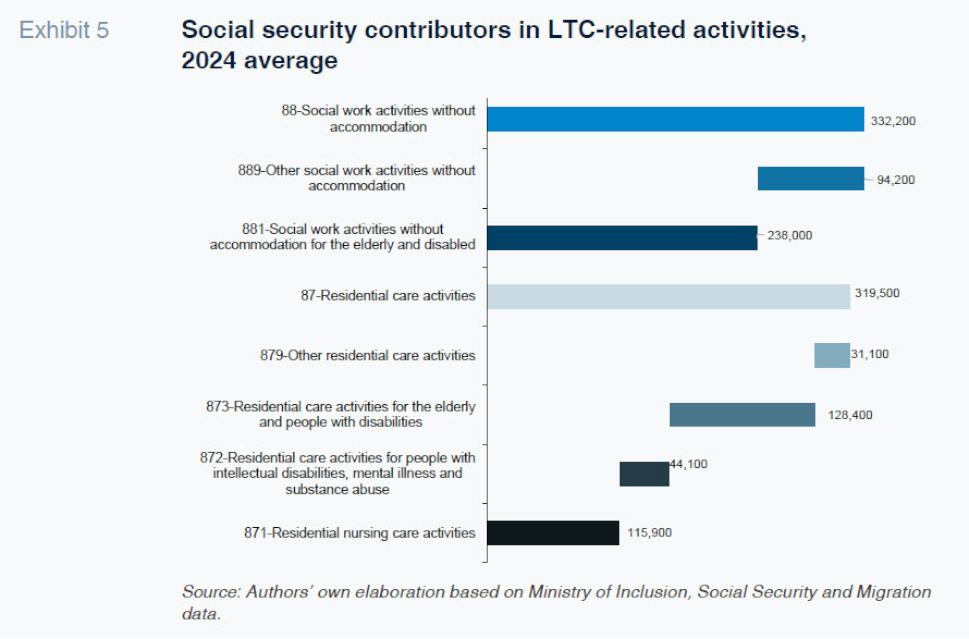

In residential care establishments, the number of social security affiliates has increased by over 40%, from approximately 226,000 workers in 2014 to nearly 320,000 in 2024. This growth has been even more pronounced in social service activities without accommodation, including home care for dependent individuals. This segment has expanded by 73% in the same period, reaching more than 330,000 workers. In sum, the long-term care workforce in Spain stands at over 650,000 people.

Population ageing has also influenced the breakdown of tasks associated with the provision of social services, where a very significant share of workers provides eldercare services. This trend is particularly pronounced in social service activities without accommodation (NACE code: 88), where 238,000 of 332,000 workers (over 70% of the total), are directly involved in caring for older people and people with disabilities.

In residential care establishments, which provide more complex and comprehensive care services, the task breakdown is more balanced. Approximately 40% of these workers are involved in care for the elderly, one-third work in the provision of healthcare, and the approximately remaining 25% are divided between caring for people with disabilities and other care activities. This greater dispersion of functions reflects the range of services provided in residential care, which include ongoing assistance, rehabilitation, medical supervision and accommodation.

Narrowing down the analysis to focus on workers devoted exclusively to LTC [5] occupations , two structural traits stand out: the majority share of female professionals and the gradual ageing of the sector’s labour force. Around 85% of formally employed care workers are women, compared to an average of 46% in the overall economy. In addition, more than half of the people employed in the provision of LTC are over the age of 45: 53% of the people employed in residential establishments and 58% of those employed in social service activities without accommodation (INE, 2024), pointing to growing pressures on the attraction of professionalized workers as they start to retire.

Hence, this reality raises two interconnected issues. Firstly, the advanced age of some of these workers and the physical demands inherent in care work translate into a higher incidence of musculoskeletal disorders that often result in higher levels of absenteeism based on health grounds. Secondly, the relatively advanced average age of this workforce makes it vital to plan for orderly generational replacement against the backdrop of sharp growth in demand for dependent care.

Precarious working conditions and staff retention

These structural issues are compounded by adverse labour conditions which are seriously impeding the sector’s ability to attract and retain professionals. Employment in the care sector is marked by high levels of temporary employment, even after the recent labour market reform: nearly one in every four workers recorded in residential establishments relies on a temporary contract, which is well above the country average (13%). Moreover, in social work activities without accommodation, the percentage of permanent contracts (60%) is 13 percentage points below the economy average (73%), likewise indicating reduced labour stability in this segment (Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration).

Turning to pay, the sector also presents a significant gap with respect to the country’s average worker. The average gross annual wage of workers in residential establishments stood at around 17,200 euros in 2023, while the average in social work activities without accommodation was 16,400 euros. These figures represent approximately 60% of the national average annual wage (26,600 euros), a gap of nearly 10,000 euros (INE, 2023).

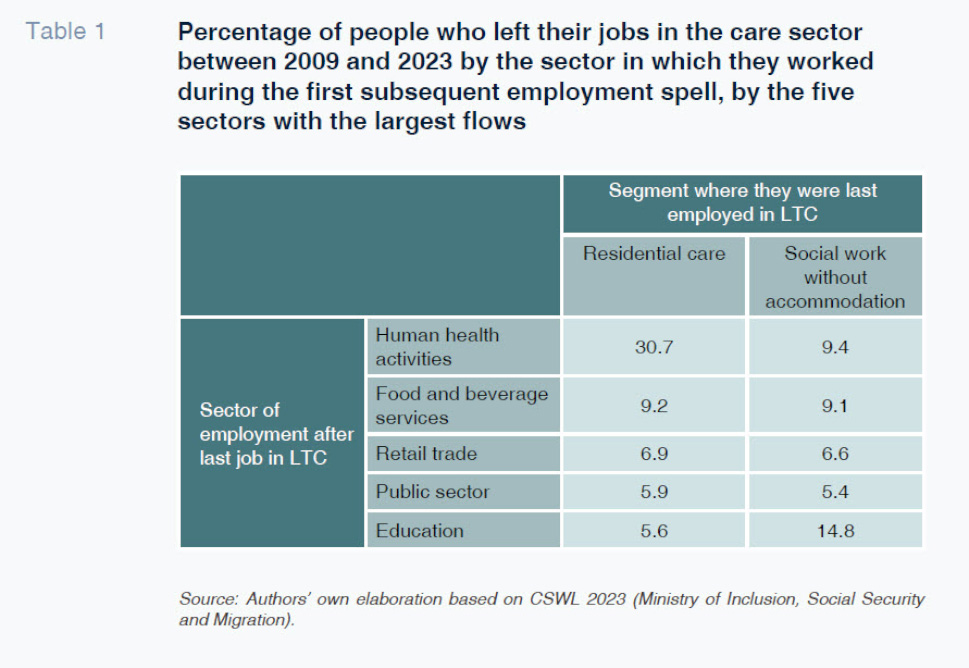

Given this backdrop of precarious working conditions, physicality and relative contractual instability, a considerable share of workers is abandoning the sector for areas offering better working conditions. The authors’ own estimates, based on the Continuous Sample of Working Lives (CSWL, Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration, 2023), indicate that 30.7% of the people who used to work in residential care establishments have since transitioned to the health sector, and that 9.4% of those formerly employed in social work without accommodation have followed the same path.

Although the analysis does not allow us to establish a direct cause-and-effect relationship between sectoral transitions and improved labour conditions, the data clearly reveal a consistent pattern: those abandoning the care sector between 2021 and 2023 experienced, on average, an increase of 2,200 euros in their annual social security contribution bases, which represents a raise of over 10% compared to their previous jobs. The improvement observed suggests that transitioning to the healthcare and education sectors appear to be driven not only by a desire for job stability or professional development, but also by wage incentives that are clearly more attractive than those offered by the LTC sector and that might play an important role on retaining these professionals.

Conclusions

The long-term care system in Spain is at a turning point. Population ageing, the consolidation of the right to formal care and autonomy and the structural transformation of provision of care towards a deinstitutionalised model are exerting a pressure on the dependent care system that is set to intensify in the coming years.

From a quantitative perspective, growth in sectoral employment is managing to cover at least some of the recent surge in demand. However, working conditions —low pay and recognition, contractual instability, physical strain and an ageing workforce—are eroding that base and pose considerable challenges in the medium and long term. The loss of human capital to sectors offering better conditions and pay is just one example of the fragility of a model that aspires to expand and improve its quality in the years ahead.

The transformation of the long-term care system, however, will not be possible without an increased budgetary allocation to accompany the regulatory and legislative changes, part of which have been supported by the Spanish Recovery and Resilience Plan. This funding is needed both to address the demands arising from demographic ageing and to improve the working conditions of LTC staff. It is a prerequisite for ensuring dignified care as well as the sustainability and professionalisation of the sector over the medium term. Yet such an increase in resources also entails a significant fiscal challenge, in an economic and geopolitical context in which other strategic areas—including defence, pensions, and ecological transition— are also demanding substantial increases in public expenditure.

To achieve their objectives, the transformations underway must be underpinned by sustained political commitment and sufficient resources to guarantee equitable access to quality care—an essential social right of the twenty-first century.

Notes

The methodological detail of these estimates, prepared by the authors of this paper, is provided in the Ministry of Social Rights, Consumption and 2030 Agenda document (2025).

This figure does not encompass total employment in the care sector, which should include other types of occupations outside of primary and secondary care provision, such as indirect care jobs.

This scenario assumes a gradual increase in the minimum FTE staff ratios per dependent individual by type of service (day and night centres; residential care; and at-home care). We assume in our estimates that the ratios stipulated in the Agreement on Common Certification and Quality Criteria for SAAD centres and services, dated 28 July 2022, are met for residential establishments and day centres by 2030, along with the intensities per person and degree of dependency laid down in Royal Decree 675/2023. These ratios are broken down in Tables 3, 4 and 5 of the Ministry of Social Rights, Consumption and 2030 Agenda report (2025).

The labour cost estimates consider the social security contributions (Annual Labour Cost Survey, INE) for 2016-2023, which are around 28% of total labour costs, and feature wage increases based on the collective bargaining agreement in place until 2026 (annual growth of 2.5%) and in line with the outlook for CPI in subsequent years (2.2%). To express these figures relative to GDP, we relied on the nominal GDP series from the April 2025 World Economic Outlook published by the International Monetary Fund. The total labour cost reflects the wage bill of all sector workers irrespective of the level of government responsible for their payment.

Thanks to the granularity of the Labour Force Survey microdata, we were able to exclude occupations not related to caring for dependent individuals (such as child carers or gardening personnel), which resulted in excluding 9% of employment in residential care and 12% in social services without accommodation.

References

Marina Asensio Vázquez, Cristina García Ciria and Gonzalo López Molina. Afi