Europe’s systemic challenge or why underestimating Russia and the axis of autocracies is a mistake

Europe’s assumptions about Russia’s weakness and the limits of autocracies have been upended by Moscow’s resilience in war and economic mobilization. Meeting this challenge requires a bolder strategy, with higher defence spending, modern technologies, and deeper European cooperation.

Abstract: Europe is facing the most profound systemic challenge since the end of the Cold War, as misconceptions about Russia’s economic weakness and the resilience of autocracies have obscured the scale of the threat. Measured in purchasing power parity, Russia’s economy is the largest in Europe, and its military spending—at nearly 7% of GDP and over a third of its federal budget—places it on par with Europe collectively. This concentration of resources, combined with hybrid warfare and sabotage operations, has enabled Russia to sustain its war in Ukraine despite sanctions. At the same time, China’s state-led growth model and technological advances add to the challenge, highlighting the ability of autocracies to mobilize resources for strategic aims. For Europe, incremental responses will not suffice. A bold strategy is needed, encompassing increased defence spending, investment in modern military technologies, and deeper cooperation through joint procurement and shared assets. The ultimate test for European democracies is to demonstrate their capacity to prioritize security and growth while maintaining cohesion in the face of an assertive axis of autocracies.

Introduction: Illusions on democracies and autocracies

Public debates about the contest between democracies and autocracies are often clouded by illusions and misconceptions. On one side, there is the comforting notion that liberal democracies, by virtue of their economic weight and moral appeal, are destined to prevail. On the other, there is a growing chorus claiming that autocracies are more effective, more resilient, and better suited for the geopolitical rivalries of the 21st century. Both views are misleading, and both can prevent Europe from facing its systemic challenge with clarity.

How can a country with an economy smaller than Italy’s destabilize an entire continent? Indeed, by conventional measures, Russia’s GDP is smaller than that of Italy. This fuels the widespread misconception –famously echoed by Barack Obama, who called Russia a “regional power” [1] – that Europe can easily prevail over Moscow. Yet this view conceals more than it reveals. At least since 2005, [2] Vladimir Putin has consistently framed the collapse of the Soviet Union as a “geopolitical tragedy”, and his policies show a persistent determination to restore Russian power that belies the country’s apparent economic size. Putin’s geopolitical ambition is encapsulated in his so-called five seas strategy—a vision of asserting Russian influence across the Black, Caspian, Azov, Baltic, and White seas as interconnected theatres of power. [3] The puzzle is clear: how can a state that looks minor on paper sustain such a major geopolitical challenge?

A second misconception further adds to confusion: the belief that autocracies enjoy systemic advantages over democracies. Commentators frequently point to China’s rise as evidence. And while China’s rise is truly impressive, this should not be understood as a general pattern for autocracies. Empirical research by Funke et al. (2023) documents how countries with populist leaders fare worse. China’s GDP per capita still remains below that of advanced western countries and consumption levels are even lower. Few citizens would willingly accept giving up their freedom for autocratic rule. And yet, the fact that living in a democracy is more comfortable, both in terms of personal liberties as well as economic performance of the country does not automatically mean that democracies prevail in a systemic challenge. Both within Western countries as well as from outside, the democratic model is contested, even if autocracies face numerous disadvantages.

When misconceptions lead us to underestimate adversaries like Russia, the strategic consequences for Europe can be severe. In the next section, we therefore aim to understand the sources of misconception and clarify the data. We then develop a policy agenda for Europe focusing on security and re-armament.

Sources of geopolitical misconceptions

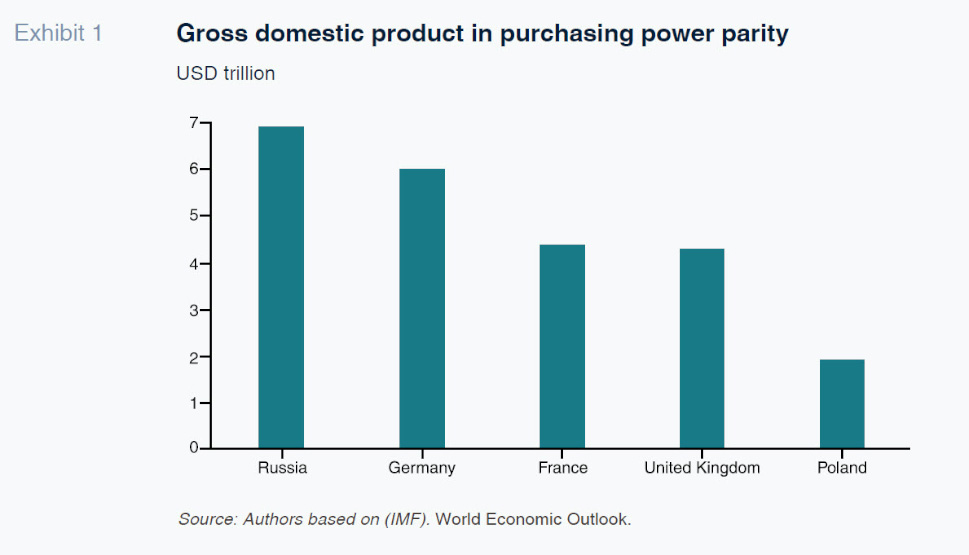

There are four major sources of misconception leading to underestimating the systemic challenge Europe faces. First, Russia remains the largest economy of Europe in purchasing power parity (see Exhibit 1) despite its relatively small size in conventional GDP measures. Typically, the size of economies is compared in terms of GDP measured in U.S. dollars. Yet, that comparison is only useful if one wants to compare the capacity to buy internationally traded goods. In terms of the capacity to produce goods and hire soldiers, what matters is purchasing power parity (PPP) – i.e. a GDP measure adjusted for the major differences in price levels. By that measure, Russia has a larger economy than even Germany.

Obviously, Russia is a smaller economy than that of the EU or Western Europe combined. We therefore will come back to the importance of effectively pooling European countries’ resources to prevail in this systemic conflict.

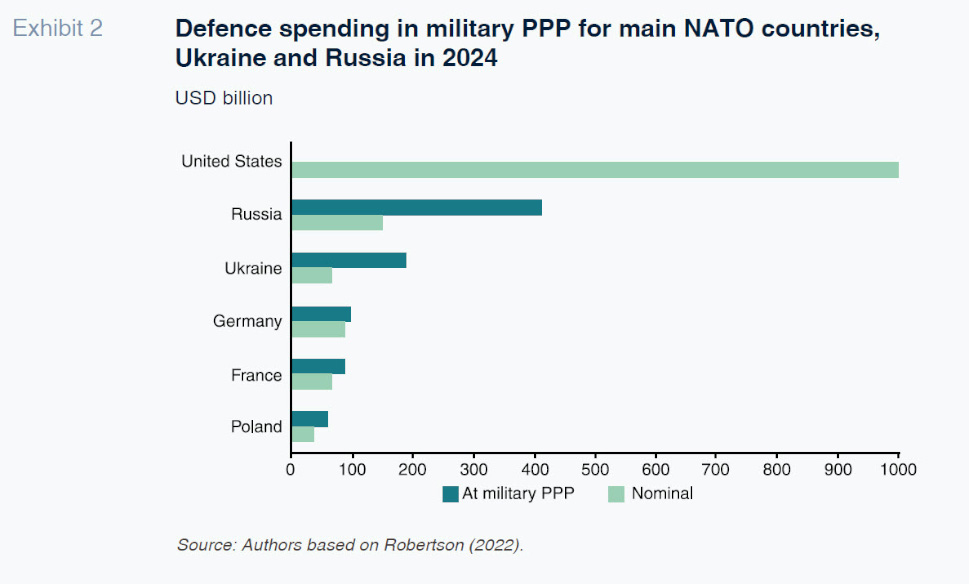

Second, it is useful to compare defence spending across major powers and document the importance of price differences for both military equipment as well as for soldiers. The so-called military PPP developed by Robertson (2022) is applied to defence spending and shown in Exhibit 2. As the exhibit reveals, Russia’s war economy is large compared to Europe and growing. Russia’s war economy has further increased the production of military goods and has been able to access Western advanced technology despite sanctions (Hilgenstock et al., 2025, Bilousova et al., 2024). The comparison of military spending in PPP shows that Russia is on par with European countries collectively. According to IISS, Europe spent even less than Russia measured in PPP in 2024. [4]

Third, the war in Ukraine consumes large amounts of military equipment on both sides and both sides suffer heavy casualties. In a systemic challenge, the political capacity to concentrate resources on specific purposes will thus be decisive. Russia has devoted substantial resources to its military production. It spends almost 7% of its GDP on its military and more than 35% of its federal budget – numbers far larger than those of Western Europe. It also forces large numbers of its citizens to fight in Ukraine, with many casualties.

The importance of resource concentration for systemic rivalry goes beyond military spending. Belton (2022)’s book “Putin’s people” documents how the KGB took back Russia and then took on the West. It is a masterpiece showing how Putin acquired financial and political control of a vast and resource-rich economy. The capacity to use these resources is a highly valuable strategic asset, for example when it comes to influence operations and acts of hybrid war. Edwards and Seidenstein (2025) document the huge scale of Russia’s sabotage operations against Europe’s critical infrastructure, affecting now countries in all of Europe. Also influence operations and cyber attacks are on the rise (Demertzis and Wolff, 2020).

Finally, while populist leaders may not have well performing economies, China’s autocracy is focused and determined to achieve high growth and challenge Europe. In fact, China found a special model of combining heavy handed state intervention based on control of massive resources with fierce private sector competition. This state-led growth model has driven rapid innovation and growth, with China now at the technological frontier in several products, including for example electric cars. This is a direct challenge to the European economic model– even if suppression of consumption and high levels of inequality mean that many in China do not even benefit much from the economic miracle.

In sum, autocracies are not doing better and certainly conditions for citizens can be quite harsh, be that economically or in terms of personal liberties. But autocracies have the capacity to concentrate resources to pursue strategic aims. The combination of a geopolitically determined Russia with large military capabilities and the economic rise of China represent a fundamental challenge to Europe, even more so at a moment when the U.S. cannot be trusted as a reliable partner.

What needs to be done

In short, the shaping of a new world order is ongoing. China and Russia are leading the changes, and their new confidence was perhaps best expressed in the recent military parade in Beijing that also involved the North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un. Meanwhile, the U.S. is withdrawing from the world. These are fundamental challenges to the European Union and all the countries of Western Europe. Gradual and incremental change will likely be insufficient. Instead, a bold strategy is needed for both the capability to defend and the ability to grow. The ultimate political challenge is to ensure that our democracies prioritize security and growth, thereby accepting and navigating unavoidable trade-offs. The challenge is thus not only one of means, but also a direct challenge to the system. Ultimately, democracies need to show they can manage to prioritise what is needed for self-preservation.

Boosting European military capacities

Europe needs to step up to face its systemic challenge. This is even more important as it is fair to expect that some of the roughly 80,000 U.S. troops in Europe will leave the continent over the next several years.

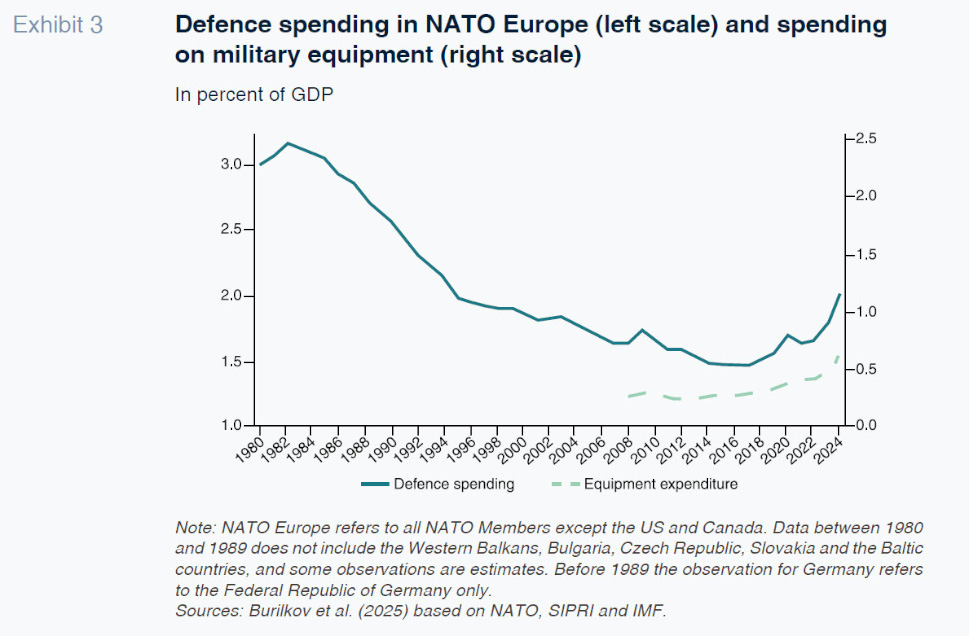

Of course, European democracies have not been sitting idle in the last few years. Since Russia’s invasion of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 and since the full-scale invasion and the war ongoing in Ukraine since 2022, defence spending has gone up (Exhibit 3). As an important part of the rise in defence spending, spending for military equipment has more than doubled.

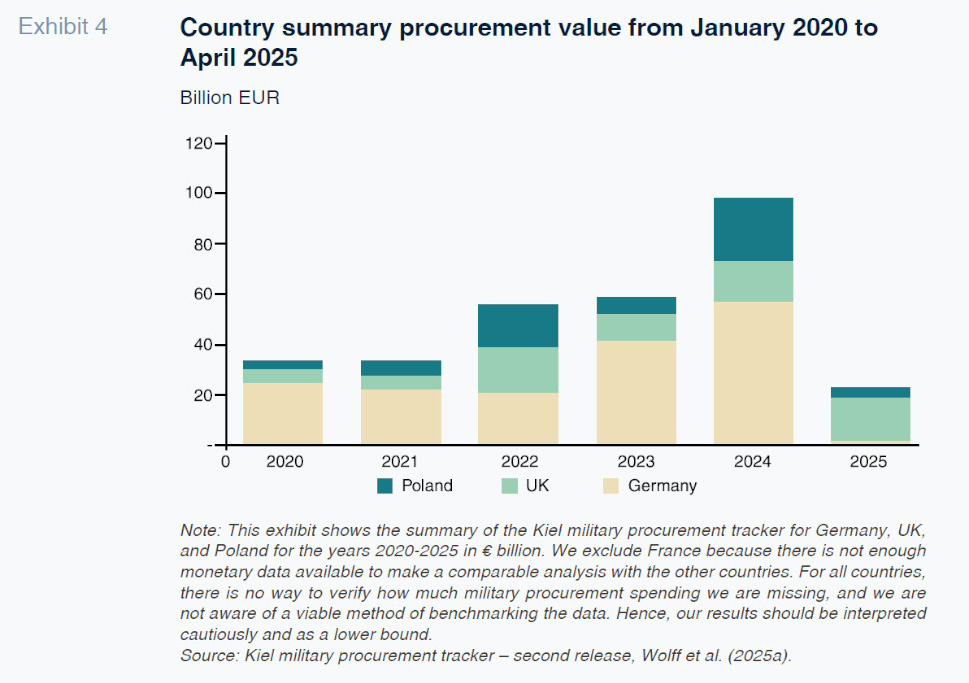

Defence spending is set to increase further with the new NATO commitments to reach 3.5% of GDP. This represents a substantial fiscal burden to European societies. As defence spending is increasing, however, it will be important to ensure an effective European rearmament strategy. In original new research, we studied in detail the military procurement in Germany, the UK and Poland as well as with more limited granularity in France (Burilkov et al., 2025). Exhibit 4 provides a summary of the rising procurement amounts – and documents that within Europe Germany has become a leading country in procuring military equipment. Our detailed study shows significant gaps in a modernisation agenda of Europe’s armed forces, despite these rising procurement numbers.

More military spending does not automatically and immediately translate into military capabilities, especially if the defence industrial base is strained. Price increases for military equipment might absorb large parts of budget increases, which will be particularly the case if supply is constrained, i.e., the supply elasticity of equipment is low, an issue also highlighted by the former top U.S. commander in Europe (Cavoli, 2025). Burilkov et al. (2024) document that the U.S. military defence industrial base is currently facing substantial strains as visible in delayed deliveries. Spending and delivery do not automatically correspond as many complex products are delivered only years after payments start. More importantly, the equipment spending might be focused on the wrong type of equipment. Modernisation needs challenge traditional procurement processes – certainly a significant problem in Europe. For example, purchasing 3D printers for mass drone production might be more effective than developing advanced new weapon systems but will require breaking with traditions. Finally, equipment spending might only just compensate for the depreciation of existing equipment stocks and fill gaps in Europe’s depleted stocks after decades of peace dividend.

On the upside, however, it is worthwhile to highlight that Ukraine is increasingly producing with its own defence industrial base. Mass production of drones – including very long-range models – cruise missiles, tanks, and artillery has compensated for fluctuations in Western arms deliveries. This “porcupine strategy” has done much to enable continued organised Ukrainian resistance. It also bodes well for post-war Ukraine’s capability to resist any potential further Russian aggression, as well as the potential of Ukraine to become a major contributor to the broader European defence ecosystem (Kirkegaard, 2025).

Meanwhile, the dependency on foreign production and technology is a growing concern in Europe. It is a formidable technological challenge as domestic procurement and production remain dominated by established technology – despite increasing evidence that in peer warfare established technology plays a smaller role than drones and missiles. Europe needs to urgently focus on a modernisation strategy with greater emphasis on missiles, drones and automatic systems. It also needs to reduce its geopolitical dependency on the U.S. that is perhaps most visible in the import of high-tech military equipment.

Finally, as European nations rearm, they cannot ignore the European dimension of rearmament. One dimension concerns the market structures for defence products: Europe’s governance for arming needs to change to ensure costs are brought down and funding made available (e.g. Wolff et al., 2025). Joint purchases are central to ensure scale while competition is needed to ensure technological leadership – both are critical for bringing down prices at a moment of rising demand.

The other dimension goes well beyond increasing joint purchases for equipment and jointly developing new technology. Ultimately, European countries need to consider deeper European military cooperation to pool their resources more effectively. Conceptually, there are two extreme models conceivable. In one, only the U.S. has the capacity to lead in the context of NATO. Currently, the U.S. serves as the anchor ensuring cooperation among European countries and stepping in with its own capacities wherever deterrence by European countries alone is not credible. The other extreme would be a fully integrated European army with a single European political and military command.

The former has become an untenable dependency on an ally that European countries do not trust anymore. The latter remains an unrealistic goal given the limited political ambitions of our current leadership. Policy makers should thus work on the grey zone in between these two extremes. A logical next step would be more jointly owned strategic assets such as intelligence satellites to reduce the fiscal burden for every European country rearming. Deeper integrated command structures across European armies following the NATO model would represent a more ambitious deepening of cooperation.

Conclusions

Europe is experiencing the biggest systemic challenge certainly since the end of the cold war. While US$-based GDP measures suggest that Russia is relatively small, we have shown that its defence spending is much higher and measured in PPP, its economy remains the largest on the continent. The common misconception that autocracies will eventually fail to deliver ignores their capacity to concentrate wealth and power to pursue domestic and foreign geopolitical goals.

Europe should thus be under no illusions. European democracies need to prove their capacity to mobilise resources for the key challenges of enhancing security and boosting growth while protecting climate. The double challenge of a war in Europe and a direct challenge by China to the EU’s economic model requires bold action. Here we have sketched the military dimension and argued for: (1) focused investments in new technologies that are more effective in modern warfare, (2) a bold strategy to boost domestic technologies and reduce excessive dependencies on U.S. military technology, (3) a European re-armement strategy focussing on scale through joint procurement and a European governance approach to reduce the fiscal costs at a moment of rising defence budgets; and, last but not least, (4) a serious debate on how military cooperation across European countries can be effectively and quickly enhanced.

In the economic sphere, the challenges are equally large and have been outlined by Letta (2024) and Draghi (2024). The bottom line is that at a time of substantial changes, European societies need to re-learn the importance of adaptation, creative destruction and innovation. This resource mobilisation is a major cost to societies – and the question of burden sharing becomes central.

Notes

References

BELTON, C. (2022).

Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took On the West. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

BILOUSOVA, O., HILGENSTOCK, b., RIBAKOVA, E., SHAPOVAL, N., VLAYSUK, A., & VLASIUK, V. (2024).

Challenges of export controls enforcement: how Russia continues to import components for its military production. Kyiv, Ukraine: KSE Institute.

https://kse.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Challenges-of-Export-Controls-Enforcement.pdf BURILKOV, A., BUSHNELL, K., MEJINO-LOPEZ, J., MORGAN, T., and WOLFF, G. (2025). Fit for War by 2030? European Rearmament Efforts vis-à-vis Russia. Kiel Report 3.

https://www.ifw-kiel.de/de/publikationen/fit-for-war-by-2030-european-rearmament-efforts-vis-a-vis-russia-34350/ BURILKOV, A., MEJINO-LOPEZ, J., and WOLFF, G. B. (2024). The US defence industrial base can no longer reliably supply Europe.

Bruegel Analysis.

https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2024-12/the-us-defence-industrial-base-can-no-longer-reliably-supply-europe-10561.pdf CAVOLI, CH. G. (2025). Statement Of General Christopher G. Cavoli, United States Army United States European Command 3 April 2025. United States Senate.

https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/general_cavoli_opening_statements.pdf DEMERTZIS, M., and WOLFF, G. (2020). Hybrid and cybersecurity threats and the European Union’s financial system.

Journal of Financial Regulation, 6(2), 306-316. Oxford University Press.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jfr/fjaa006 DRAGHI, M. (2024).

The Future of European Competitiveness.

https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en EDWARDS, CH., and SEIDENSTEIN, N. (2025). The Scale of Russian sabotage operations against Europe’s critical infrastructure.

IISS Papers.

https://www.iiss.org/research-paper/2025/08/the-scale-of-russian--sabotage-operations--against-europes-critical--infrastructure/ FUNKE, M., SCHULARICK, M., and TREBESCH, C. (2023). Populist Leaders and the Economy.

American Economic Review, 113(12), 3249–3288.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20202045 HILGENSTOCK, B., RIBAKOVA, E., VLASYUK, A., & WOLFFf, G. (2025). Enforcing export controls learning from and using the financial system.

Global Policy, 16, 190–199.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13463 KIRKEGAARD, J. F. (2025). Ukraine: European democracy’s affordable arsenal.

Policy Brief, 10/2025. Bruegel.

https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/ukraine-european-democracys-affordable-arsenal LETTA, E. (2024). Much more than a market.

https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/ny3j24sm/much-more-than-a-market-report-by-enrico-letta.pdf OBAMA, B. (March 25, 2014). Russia is a regional power, acting out of weakness and not strength. Speech.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PBJKbaqMEzI ROBERTSON, P. (2022). ‘The real military balance: International comparisons of defense spending’.

Review of Income and Wealth, 68(3), 797-818.

https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12536 WOLFF, G., BURILKOV, A., BUSHNELL, K., KHARITONOV, I., MEJINO-LOPEZ, J., and MORGAN, T. (2025).

Kiel military procurement tracker – release 2.0. Kiel Institute.

https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/kielmilitary-procurement-tracker-33232/ WOLFF, G., STEINBACH, A., and ZETTELMEYER, J. (2025).The governance and funding of European rearmament.

Policy Brief, 15/2025. Bruegel.

https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/governance-and-funding-european-rearmament

Guntram Wolff. Solvay Brussels School at Université libre de Bruxelles and Bruegel