The ECB’s next challenge: Monetary policymaking in an age of uncertainty

With inflation falling and rates now below peak, the ECB has entered a new phase of policymaking focused less on neutrality and more on agility. In an increasingly volatile global environment, credibility and adaptability, rather than pre-set trajectories, will define the path forward.

Abstract: On 5 June 2025, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank lowered its main policy rates by 25 basis points, bringing the deposit facility rate down to 2%. While this move does not yet return rates to their estimated long-term neutral level—and may not be the final adjustment—it marks an important shift. Specifically, it brings to a close the ECB’s three-phase response to the inflation shock triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Looking ahead, the Governing Council will place less emphasis on whether interest rates are exactly at the “right level” for long-term price stability. Instead, the focus will shift toward how and when to respond to new external developments. In this new phase, the ECB aims to remain flexible and responsive while continuing to uphold its credibility with markets and the public. This forward-looking approach was outlined in a strategy assessment published by the ECB on 30 June, drawing on lessons from recent years. Concern for the neutrality of monetary policy will have to wait for a more predictable economic and political climate.

Introduction

European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde announced that the Governing Council would reduce the ECB’s key policy rates by 25 basis points (or 0.25 percent) on 5 June 2025, bringing the rate at which commercial deposits held at the ECB are remunerated –the “deposit facility rate”– down to 2 percent. Given that headline inflation in the euro area was just under 2 percent according to flash estimates for May, this move brings inflation-adjusted (or ‘real’) remuneration of commercial deposits with the ECB close to zero, which most Governing Council members agree is neither restrictive nor accommodating.

When asked by reporters whether this move would place the ECB’s policy rates close to the level at which they would be neutral with respect to longer-term inflation and growth prospects, Lagarde insisted that such concerns were no longer the focus for attention. Although the Governing Council recently had intense debates about the long-term neutral rate –called r-star (or r*)– Lagarde insisted that the possibility had not even come up in the Governing Council’s deliberations. “The neutral rate is predicated on the absence of shock: great equilibrium, no shock,” Lagarde explained. ‘For the moment, we are facing significant uncertainty.’

Lagarde even rejected the possibility that the ECB’s monetary policy has a specific ‘direction of travel’. Instead, she underscored that this latest policy move puts the Governing Council ‘in a good position’ to respond to global events. Further monetary policy changes are possible – and Lagarde concluded her opening remarks by asserting that “we stand ready to adjust all our instruments within our mandate to ensure that inflation stabilises sustainably at our medium-term target” – but the implicit qualification is that such adjustments would be reactive and no longer formed part of the Governing Council’s strategy for disinflation. [1]

Lagarde’s comments suggest that the Governing Council’s three-phase response to the inflation shock that followed the COVID-19 pandemic and that was exacerbated by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has come to an end. ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane agrees, arguing in a speech on 24 June that: “there has been sufficient progress in returning inflation to target to consider that this monetary challenge is largely completed.”

[2] If so, it is worth asking whether such optimism on the part of the Governing Council is warranted. It is also worth considering whether and how the ECB’s monetary policy will change now that ‘uncertainty’ has come to dominate the Governing Council’s deliberations. The Governing Council has worked hard over the past three years to shore up the credibility of its commitment to price stability in the eyes of market participants; within the framework of the strategy assessment published on 30 June, demonstrating its ‘agility’ to respond to current events is equally if not more important.

[3]

The three phases of disinflation

The Governing Council’s response to the acceleration of price inflation in the euro area began in July 2022, with a decision to increase the deposit facility rate by 50 basis points (or one half of 1 percent) to 0 percent. This move marked an end to the practice of taxing commercial deposits held above the regulatory requirements that had been introduced during the long period of very low inflation and slow economic performance that followed the European sovereign debt crisis and that intensified during the pandemic. Governing Council members noted the acceleration of inflation after the pandemic, but they believed they could ‘look through’ the sudden increase in prices as a response to the confusion the pandemic created in global supply chains and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine created in energy markets (Jones, 2022).

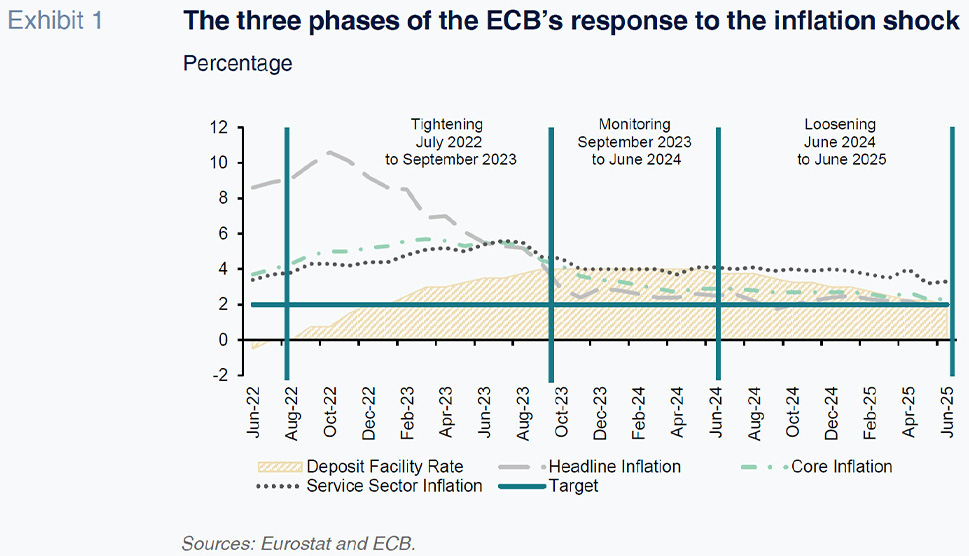

Once it became clear that these price increases were feeding into ‘core inflation’ – meaning inflation that excludes the influence of price movements for energy, food, alcohol, and tobacco – and “service sector inflation”, however, Governing Council members acknowledged this could result in the emergence of a self-reinforcing price-wage spiral if left unaddressed. Therefore, they began to pull up policy rates in a series of large movements of between 50 and 75 basis points until the deposit facility rate peaked at 4 percent in September 2023. This series of sharp movements coincided with a rapid deceleration of headline price inflation from a peak of 10.6 percent in October 2022 to 4.3 percent the following September, but core and service sector price increases remained more persistent. (See Exhibit 1).

The challenge for the Governing Council was to assess whether the deceleration in headline inflation would continue or whether the underlying momentum in core and service sector inflation would prevent the Governing Council from bringing the headline rate down to its target of a medium-term inflation of close to 2 percent. The economic forecasts provided by the ECB’s staff showed headline inflation converging on target in 2025, but the persistence of core and service sector inflation gave cause for concern, as did the acceleration in wage growth as workers pushed to recover real purchasing power in the face of persistently higher prices. Therefore, the Governing Council shifted from tightening its policy instruments to monitoring the impact of higher policy rates on both price inflation and underlying economic performance. That monitoring phase continued for nine months until the Governing Council began to lower its policy rates on 6 June 2024. [4]

The reduction in policy rates was both more gradual and less extensive than the tightening that took place during the first phase. The Governing Council moved in increments of 25 basis points, often on a quarterly basis rather than in consecutive monetary policy meetings. The concern was for overshooting in a way that would require the Governing Council to raise policy rates again in response to an acceleration in inflation rates. As this process of gradual loosening progressed, however, Governing Council members became more confident that core inflation would move down to target alongside headline numbers and they became more cautious about the impact of prolonged high interest rates on underlying economic performance. Service sector inflation remained a cause for concern, as did underlying wage bargaining trends, but Governing Council members felt confident enough to increase the pace of rate reductions even as they engaged in ever more intense debates about where the process should stop given the difficulty of estimating the long-run neutral policy rate.

Subsequent movements in service sector inflation rates and wage bargains validated that faster approach. Although both indicators remain above the ECB’s target for overall price inflation, both also show decreasing momentum which suggests that the adjustment to higher prices is coming to an end without igniting a wage-price spiral. The ECB’s March and June 2025 forecasts confirmed this assessment to show headline inflation stabilizing at or slightly below target through 2027 – with much of the undershooting explained by the fall in energy prices; moreover, the same projections show consistent performance in terms of economic growth. [5]

The reason for underscoring this point about economic performance is that – all things being equal – the growth estimates from the March and June projections are the same even as the headline inflation estimates have come down. By implication, the improvement in inflation over the medium term is not projected to be caused by a weakening of economic performance. This explains in part why most Governing Council members believe their policy response to the post-pandemic inflation shock is coming to an end. What that assessment leaves open is whether there are other shocks on the horizon that could upset the forecasts in terms of growth, inflation, or both.

From inflation to uncertainty

The list of potential shocks to European economic performance is long and includes a wide range of different mechanisms that can exert a powerful influence on European markets. The challenge is not simply to estimate what impact a given trade deal between the European Union (EU) and the United States (U.S.) might have on supply chains, prices, profitability, or employment, but also how the EU might be affected by trade negotiations between the United States and China or other major economic actors, and whether close European economic partners will fall inside or outside safeguard provisions for European markets. Trade negotiations will also have an influence on energy markets, capital flows, and exchange rates (ECB, 2025a). The ECB has tried to develop scenario analysis to fold these possibilities into its decision making, but the possible variations are too numerous to bring into something resembling a modelling forecast.

The Governing Council’s response to this changing environment can be found in the 2025 assessment of its monetary policy strategy as published on 30 June.

[6] That assessment reaffirms the importance of having a symmetrical inflation target with a medium-term perspective (ECB, 2025b). These elements allow the Governing Council to “look through” temporary deviations in actual inflation performance on either side of the target while at the same time encouraging the Governing Council to act forcefully whenever inflation expectations in the market threaten to become unanchored from the 2 percent target. The assessment also underscores the role that the ECB can and should play in supporting the broader economic objectives of the European Union as set out in the European treaties. As part of that role, the assessment reaffirms the need to do a comprehensive proportionality assessment when setting monetary policy instruments to achieve price stability and to reinforce the functioning of the monetary transmission mechanism (ECB, 2025b).

These elements in the review are not new. In many ways they reiterate commitments made during the 2021 strategy revision. Nevertheless, this reiteration in the 2025 assessment is important given the change in context. The 2021 strategy revision came at the end of a long period of below-target inflation performance as the ECB set its instruments close to the effective lower bound (ECB, 2025a). The post-pandemic inflation shock started just after the new strategy came into effect. The Governing Council’s response to that shock was a test of the new strategy and so the reiteration of core principles is a testament to the strategy’s success.

The 2025 assessment also strikes an important note of caution: the success of the Governing Council’s response to the shock could not be taken for granted (ECB, 2025a). Although the three-phase description given above shows continuous progress, the possibility that second-order effects of inflation on wage growth, service sector and manufacturing prices could de-anchor inflation expectations in the market was real, both because supply-shocks like those associated with the pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine are becoming more common and because the mechanisms through which such shocks can propagate through the economy are increasingly less well understood. As the review makes clear, much of the uncertainty stems from the consequences of deep structural changes underway in the relationships between great powers at the international level, but also demographics, productive technology, energy, climate, and resource use (ECB, 2025a). These changes create shocks of their own; they also put downward pressure on the long-run neutral interest rate (r*).

This uncertainty creates two problems for monetary policymakers. One problem relates to the danger of overreacting in ways that could have powerful unintended consequences (Chadha, 2022). This problem could be seen in the distortions created by negative interest rates and large-scale asset purchase programmes. But they operate through other instruments as well. This problem of unintended consequences explains why the Governing Council chose to underscore the importance of conducting proportionality assessments. The other threat is that the Governing Council will do too little, too late, and so lose credibility among market participants. The 2025 strategy assessment argues that credibility was essential to its success in bringing inflation back down to target over the past three years (ECB, 2025a). Hence, in language that echoes back to the start of the ECB, ensuring the Governing Council’s commitment to its price stability mandate remains credible is the ECB’s most important contribution to its secondary mandate as well.

The 2025 strategy assessment offers two ways to shore up the Governing Council’s credibility. One is to increase the supply of relevant information to policymakers through the active use of scenario analysis alongside macro-economic forecasting (ECB, 2025b). Such scenario planning does not have to be accurate in the details to make a significant contribution to decision-making. The goal for such analysis is to point to new or different areas where policymakers might look for evidence of adverse influences, consequences, or feedback loops.

The second way to shore up credibility is to ensure that the Governing Council is prepared to act forcefully when required both should inflation appear to accelerate or, more particularly, should price inflation and policy instruments move close to the effective lower bound (ECB, 2025b). The need to be able to act forcefully at least partly explains why the Governing Council appears reluctant to continue cutting policy rates now that its three-phase response to the post-pandemic inflation shock is ending. Although further rate reductions may support macroeconomic performance, they will also move the Governing Council closer to the effective lower bound for interest rates, thus forcing Governing Council members to rely more on the use of other policy instruments when faced with the need for decisive action.

Those instruments remain in the toolkit. Some, like the targeted long term refinancing operations or outright asset purchases, are part of the new operational framework. The Governing Council will eventually need to deploy those instruments to maintain the balance sheet of the Eurosystem at a level sufficient to provide adequate liquidity to conduct monetary policy through changes in the deposit facility rate (Jones, 2024). That operational function is an additional incentive to retain some buffer in policy rates to use in case of need for decisive action. Although more unconventional monetary policy instruments have proved useful close to the effective lower bound, the unintended consequences of using those instruments to push up the inflation rate have been high and the effectiveness of relying on policy rates to achieve the same goal is greater. A similar logic holds for setting the inflation target at two percent with a symmetrical focus rather than having an asymmetrical target below but close to two percent as outlined by the first strategy review done in 2003 or below two percent with no lower bound as it was in the initial strategy drawn up when the ECB was founded in 1998.

Conclusion

The 2025 strategy assessment marks an important shift in the thinking of the Governing Council insofar as it strikes a new balance between the need for caution and the requirements for credibility in an age of heightened uncertainty. Looking beyond the ECB’s recent efforts to respond to the post-pandemic inflation shock, the assessment suggests that the Governing Council will need to develop new sources of information and new modelling techniques for the analysis underpinning its monetary policy decisions. Governing Council members will also need to strike a new balance in their communication efforts between the need to provide transparency for financial market participants and the wider public, and the need to avoid making rhetorical commitments that constrain them from reacting to developments in an agile fashion. The struggle to tame the post-pandemic inflation shock may be ending, but the challenge of making monetary policy in an age of uncertainty is only beginning. [7]

Notes

This notion of ‘agility’ appears in the 2025 strategy assessment, but it plays a central role in a recent speech delivered by the Governor of the Banque de France, François Villeroy de Galhau within the “EMU Lab” organized by Marco Buti and Giancarlo Corsetti at the Robert Schuman Centre on 19 June 2025.

The text of that speech can be found here:

https://www.bis.org/review/r250623e.htm

References

CHADHA, J. S. (2022). The Money Minders: The Parables, Trade-Offs and Lags of Central Banking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ECB. (2025a). ECB Monetary Policy Strategy Assessment – Workstream 1: A Strategic View on the Economic and Inflation Environment in the Euro Area. Occasional Paper Series, 372. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

ECB. (2025b). ECB Monetary Policy Strategy Assessment – Workstream 2: Report on Monetary Policy Tools, Strategy, and Communication. Occasional Paper Series, 372. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

JONES, E. (2022). The War in Ukraine and the European Central Bank. Survival, 64(4), 111-119.

JONES, E. (2024). Rewiring the European Central Bank. SEFO – Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 13(5), 31-38.

Erik Jones. Director of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute and Non-resident Fellow at Carnegie Europe