Revolving credit in Spain: Between financial inclusion and consumer risk

Revolving credit plays a growing but still limited role in Spain’s household borrowing landscape, offering flexible financing to consumers with limited access to conventional credit. However, its complex structure and high associated costs raise concerns around transparency, education, and regulatory oversight.

Abstract: Revolving credit has emerged as both a tool for financial inclusion and a source of concern in Spain, especially as its usage grows amid legal scrutiny and regulatory debate. Recent Supreme Court rulings demonstrate a need for clearer consumer information and greater transparency in contract terms, while European examples offer potential regulatory models. Although revolving credit remains a small share of household borrowing, close to 2%, its flexible features make it appealing to vulnerable borrowers. However, without robust consumer protection and financial education, the risk of long-term debt accumulation and exclusion from formal financial systems remains high. The implementation of Directive (EU) 2023/2225 provides an opportunity for Spain to enhance legal certainty, implement international best practices, and strike a better balance between access and safeguards.

Revolving credit, a reality in Spain and Europe

In recent months, revolving credit has been the subject of growing litigation, highlighting the need to ensure the provision of transparent information. Two recent Supreme Court rulings are a case in point. [1] In both rulings, the Supreme Court found that the interest rate clause in the revolving credit card agreements fails to surpass the transparency threshold when the consumer is not provided with clear, understandable and sufficient information prior to arrangement about how the credit works, its risks and the financial consequences of the repayment system.

Neither sentence in any way questions the validity of this financial product and both confirm that their rates of interest should be compared with the rates on this class of product, which are different from other consumer finance products.

Note, elsewhere, that the characteristics of the revolving credit products marketed in Spain are similar to the products in the same category on offer in other European countries.

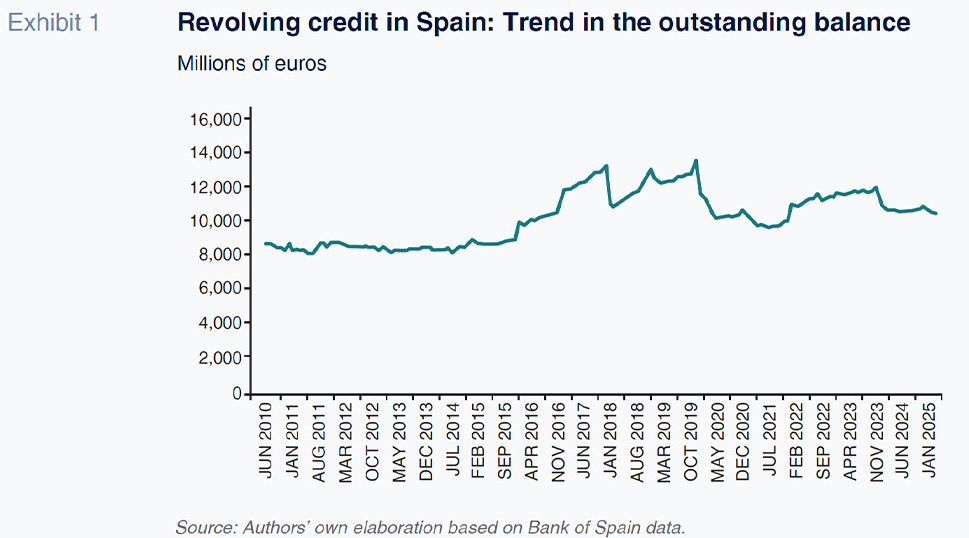

The balance of outstanding revolving credit currently stands at around €10 billion in Spain, implying very moderate growth from the €8 billion recorded in 2010, which is as far back as the information goes.

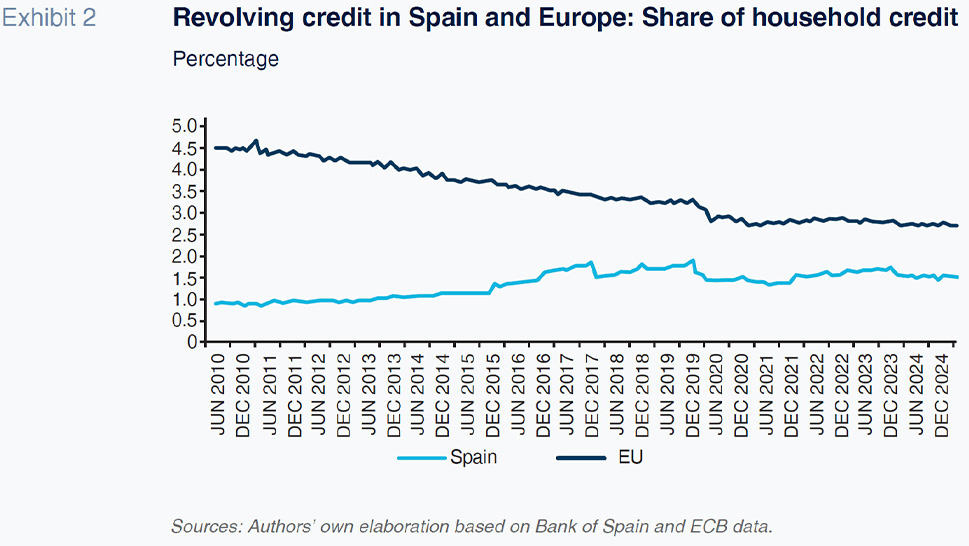

Despite the modest growth in the outstanding balance of revolving credit, this product’s share of total household credit has almost doubled, from 1% in 2010 to close to 2% today. That is attributable to the sizeable contraction in the outstanding balance of household credit since the Great Financial Crisis, which unleashed a long process of deleveraging.

At the overall European level, the outstanding balance of revolving credit stands at around €180 billion, which is 3% of total household credit, compared to a little over 4% in 2010.

We can conclude, therefore, that, shaped by diverging trends (downward in the EU and upward in Spain), the share of revolving credit in Spain is converging towards European levels, of around 2% of total household credit.

This is a relatively small share – small enough to stave off the risk of financial instability, but it is significant in certain segments for whom it may be the only available alternative, facilitating their financial inclusion.

In this context, the idea is not to cast a negative light on the product in general, but rather to inject rigour and transparency into its analysis and, if possible, embrace best regulatory practices from other European countries. Those are the aims of the next two sections of this paper.

Revolving versus conventional credit: Financial inclusion and risks

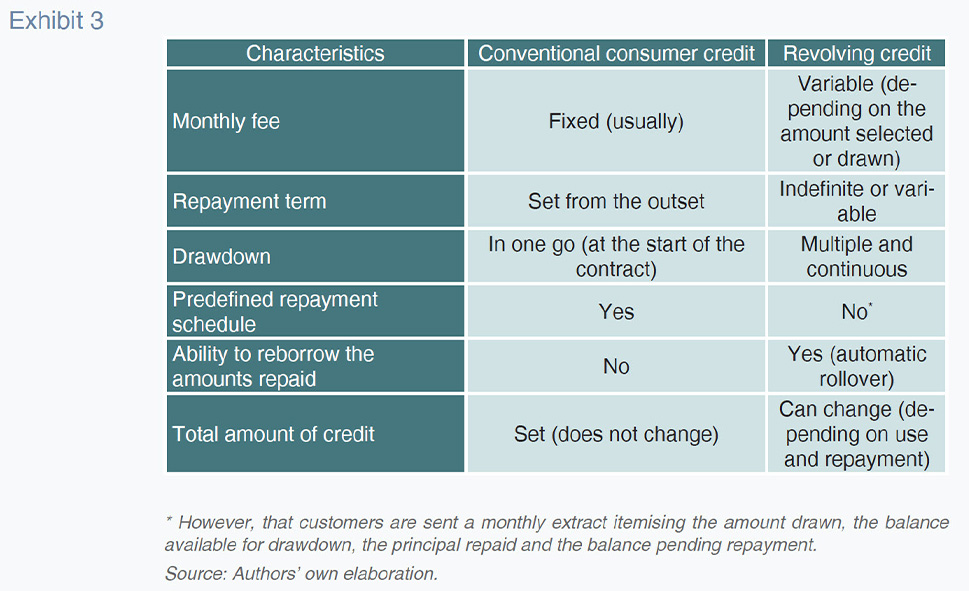

Revolving credit is defined as “interest-bearing credit with no set duration or of a defined duration that can be rolled over automatically that is granted to individuals who are not required to repay the credit drawn in full at the end of the agreed settlement period” in Article 33 bis of Ministerial Order EHA/2899/2011 on banking service transparency and customer protection.

The next table compares and contrasts conventional and revolving credit:

As gleaned from the table above, the key traits of the revolving credit product include: i) flexibility, as it allows users to borrow up to a set limit and repay it over time in amounts that can be adjusted within certain bands; ii) automatic rollover, as any capital that is repaid can be re-borrowed, working like a permanent credit line; and, iii) interest charges only on the balance effectively drawn down.

Thanks to these characteristics, revolving credit can offer a financing solution for people with irregular income streams, temporary work or without ready access to traditional products on account of their risk profiles or the inability to put up collateral. For these consumers, access to a flexible credit line may well be preferable to finding themselves completely excluded from the formal financial system or having to resort to other opaque or inadequately regulated sources of financing.

The elimination or excessive restriction of these products could have undesired consequences, such as exclusion of certain segments of the population or deviation of demand to informal circuits. As a result, the challenge posed by these instruments is guaranteeing their adequate use by means of accessible information, proportionate terms and conditions and responsible conduct by all stakeholders.

This is a prerequisite as this product is by no means risk-free. If customers decide to make small repayments or directly default, interest builds on the balance outstanding. By opting for low instalments, customers end up paying high amounts of interest, potentially drawing the loan out for years and generating a high total cost. It is therefore vital to use these types of products responsibly by making the most of the periodical information provided by the banks as part of their disclosure and transparency requirements.

The typical revolving credit customer tends to be someone who needs a quick and flexible solution for tackling liquidity issues who generally has limited access to other sources of financing.

As a result, financial education is key, as the consumer needs to understand the consequences of deferring payments or paying small instalments. Hence the importance of the information provided, diligently and proactively, by the banks.

Consumer protection: Spain versus Europe

In Spain, the main piece of consumer protection legislation in this respect is Law 16/2011 on consumer credit agreements. Ministerial Order EHA/2899/2011 on banking service transparency and customer protection and Ministerial Order ETD/699/2020 regulating consumer credit are also relevant. These orders provide guidelines about the information that must be provided to consumers, including templates designed to display the main elements of the product arranged in a simple and user-friendly way.

In addition, the Bank of Spain, duly empowered to issue rules of conduct and transparency around the provision of financial services, has formulated its own Guidelines on the governance and transparency of revolving credit, applicable since 31 December 2024. That document contains supervisory guidelines intended to help the entities comply with and implement the revolving credit governance and transparency rules, while helping create best practices and procedures in this product class.

Revolving credit borrowers tend to share a common risk profile. The standard applicant for this type of financing is someone facing liquidity tensions, with a limited or previously impaired credit history or with a history of high leverage. They are often customers without easy access to other traditional sources of financing such as conventional personal loans. As a result, the cost of risk associated with these customers is, typically, relatively high. To assess that risk, the financial institutions analyse, as they are required to do, the borrowers’ creditworthiness to ensure they are capable of repaying the debt they take on. This relatively high exposure to default risk justifies, from the perspective of the financial institutions, the application of higher rates than they charge on conventional consumer credit products.

By way of additional transparency and consumer protection tools, some European jurisdictions have set regulatory limits on the interest rates that can be applied.

Directive (EU) 2023/2225 was published at the end of 2023 (and is currently in the transposition period), reopening the debate about member states’ scope [2] to introduce measures to limit borrower rates, the equivalent annual rates (APRs) or the total costs of credit for consumers.

France, Italy, Portugal and Belgium have already opted to define limits to tighten legal certainty and predictability. These regulations vary considerably from one country to the next, particularly in terms of the maximum permitted interest rates and the consumer protection mechanisms.

France, for example, stipulates that a loan is usurious if the APR is more than one-third higher than the average APR of comparable products during the previous quarter. That average, along with the percentage above which an interest rate is considered abusive, is calculated and published by the Bank of France quarterly.

Italy defines the usury rate (tassi soglia) as the so-called average overall effective rate (TEGM) published quarterly by the Bank of Italy multiplied by 1.25 plus an additional spread of 4 percentage points, subject to a ceiling of 8 percentage points above the average rate.

Portugal has a double threshold as any loan agreement whose APR is more than 1.25 times the average for the previous quarter for the same product category or that exceeds the average APR of all consumer credit agreements by 1.5 times is deemed usury. The Bank of Portugal is responsible for publishing the maximum APRs each quarter.

Lastly, the Belgian approach is different insofar as its usury thresholds benchmark money market indices such as 3-month Euribor or 2- or 3-year bond yields, depending on the category and amount of credit. Each index is grossed up by a fixed spread and the limits are adjusted automatically when the underlying index moves by at least 75 basis points. In this case, the Federal Public Service Economy is tasked with publishing these statistics.

In these four countries the system is based on classifying loans into like categories by size and/or nature, some with more nuances than others, allowing for accurate and distortion-free comparisons.

In Spain, however, there are no usury thresholds.

The analysis of the countries to have introduced thresholds reveals certain common elements that could serve as a framework for potential future reforms in Spain:

- The existence of categories for regulatory purposes designed to facilitate the comparison of like products;

- The use of an objective and public benchmark rate;

- The establishment of predictable maximum thresholds that are revised regularly; and,

- Official publication of these thresholds to disseminate them and facilitate compliance.

Given the lack of recent Spanish regulations in this regard, it has fallen to the courts to rule on a range of matters, notably including ratification [3] of the threshold of 6 percentage points above the average APR for the category in question for the purpose of assessing profiteering in revolving credit.

The main conclusion of this analysis is it is possible to balance consumer protection, access to credit and legal certainty through comprehensible and structured regulations.

Conclusions

Revolving credit is a financial instrument which, well used and framed by sufficient transparency, can facilitate access to credit for persons with irregular income or without sufficient collateral, acting as a financial inclusion tool and preventing borrowers from being pushed into the black market for credit. Its flexibility, by providing access to funds on an ongoing basis and allowing their repayment in adjustable instalments, makes it an attractive alternative to conventional consumer finance for these segments of the population.

However, the product’s very structure implies a risk of morphing into long-term debt if the customer fails to make responsible use of the product or information provided in keeping with prevailing legislation.

The key challenge as a society is to ensure that the consumer receives enough financial education to be able to understand the terms and conditions they are agreeing to, how the credit facility works and its financial consequences so that they can take informed and reasonable decisions.

The transposition of Directive (EU) 2023/2225 into Spanish law creates the opportunity to modernise national regulations and emulate the best practices already established in other jurisdictions, such as the classification of products into like categories, the use of public benchmarks and the regular disclosure of the legal thresholds. These reforms could be accompanied by reinforced financial education for consumers and continued high disclosure standards for the lending institutions.

In a nutshell, well-regulated revolving credit has a legitimate place in a balanced financial system. The objective should be to craft a regulatory framework that combines access to credit, effective consumer protection and legal certainty for all parties.

Notes

Supreme Court Ruling of 30 January 2025, No. 154/2025 (ROJ: STS 242/2025 - ECLI: ES:TS:2025:242) and Supreme Court Ruling of 30 January 2025, No. 155/2025 (ROJ: STS 241/2025 - ECLI: ES:TS:2025:241).

Directive 2008/48/EC already contemplated this possibility, although in several member states, the interest rate limitation regulations go back further in time.

Supreme Court Sentence of 15 February 2023, No. 258/2023 (ROJ: STS 442/2023 - ECLI:ES:TS:2023:442).

References

Directive 2008/48/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2008 on credit agreements for consumers and repealing Council Directive 87/102/EEC, and its transposition into Spanish law via Law 16/2011 of 24 June 2011 on credit agreements for consumers.

Directive 2023/2225/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 on credit agreements for consumers and repealing Directive 2008/48/EC.

Spanish Law of 23 July 1908 on the annulment of usurious loan agreements.

Ministerial Order EHA/2899/2011 of 28 October 2011 on banking service transparency and customer protection.

Ministerial Order ETD/699/2020 of 24 July 2020 regulating revolving credit and amending Ministerial Order ECO/697/2004 of 11 March 2004 on the Central Credit Register, Ministerial Order EHA/1718/2010 of 11 June 2010 on banking service advertising regulation and control and Ministerial Order EHA/2899/2011 of 28 October 2011 on banking service transparency and customer protection.

Guidelines on the governance and transparency of revolving credit for financial institutions subject to Bank of Spain supervision.

European regulations: Code de la consommation (2016) (FR), Code monétaire et financier (2016) (FR), Decreto-Lei No. 133/2009, of 2 de junho (PT), Legge 7 marzo 1996, No. 108 (IT), Legge 12 luglio 2011, No. 106 (IT), Arrêté royal relatif aux coûts, aux taux, à la durée et aux modalités de remboursement des contrats de crédit soumis à l’application du livre VII du Code

de droit économique et à la fixation des indices de référence pour les taux d’intérêt variables en matière de crédits hypothécaires et de crédits à la consommation y assimilés (2016) (BE) and Code de droit économique (BE)

Aitana Bryant, Ángel Berges and Juana María Periago. Afi