Household perceptions of the Spanish economy: Growth trends and social frictions

Spain has recorded some of the eurozone’s strongest post-pandemic growth, with gains driven by tourism, immigration, and EU recovery funds. Yet, household perceptions remain mixed, shaped by inflation, tax pressures, and persistent inequality that undercut the broader economic narrative.

Abstract: Despite leading GDP growth in the eurozone since 2021, Spain’s strong economic performance has not translated into equally strong public sentiment. A new national survey reveals that while some households report financial improvement driven by wage gains and job stability, more believe their situation has worsened, citing inflation and taxes as the main causes. The disconnect between macroeconomic indicators and household sentiment is further demonstrated by continued concern over low wages, housing affordability, and inequality. Perceptions vary significantly by age, income, household composition, and political orientation, with younger, right-wing, and lower-income groups expressing greater dissatisfaction. The widespread sense of lost purchasing power, combined with sharp increases in VAT and income tax burdens since 2019, reinforces a sense of financial strain for many.

Economic performance: The heart of the matter

The Spanish economy has been one of the most dynamic since the pandemic, recording growth of 6.7%, 6.2%, 2.7% and 2.9% between 2021 and 2024. Those rates are clearly above the levels recorded in France and Germany, of 1.6% and -0.2%, respectively. Three key factors explain the momentum in growth in Spain. Firstly, the tourist sector has revisited pre-pandemic levels and emerged as a key economic growth engine for the country. Secondly, the labour force growth triggered by immigration has been a key pillar. The Bank of Spain (2025) estimates the impact of immigration at between 0.4 and 0.7 percentage points per annum between 2022 and 2024, which is equivalent to a quarter of the growth recorded during the period. Thirdly, the European recovery funds are transforming strategic sectors and are set to make a contribution to GDP growth estimated at between 0.4 and 0.5 points in 2025 and 2026, respectively (CaixaBank Research, 2025). This sharp growth has lifted employment. At the end of 2019, unemployment stood at around 14%. During the pandemic it edged towards 16%. Since 2021, it has been coming down gradually, ending the first quarter of 2025 at 11.4%. The reduction in the unemployment rate has come in tandem with sharp growth in employed immigrants. Nevertheless, Spain continues to rank poorly on unemployment, evidencing labour market weaknesses.

Despite the good GDP growth figures, the indicators that directly affect household wellbeing have fared less well. First of all, wages are particularly low in certain sectors. Employees earned an average of €28,049 in 2023 (most recent figure available), whereas in hospitality, the sector with the lowest wages, that average was just €19,985 (INE, 2025). Moreover, the jobs created in recent years have been concentrated in sectors that pay less and require less skilled workers (García and Pinto, 2025). Secondly, inflation during the post-pandemic era has hit low-income households more intensely, accentuating inequalities in real income (Romero-Jordán, 2023). Indeed, inequality remains a structural challenge, as revealed by the synthetic Gini coefficient, which, despite a small reduction relative to the crisis of 2008, remains high by comparison with other European countries (Eurostat, 2025). The situation facing the youngest households, which are facing growing housing affordability problems, is of particular concern (CaixaBank Research, 2024). Lastly, the household tax burden, via personal income tax and value-added tax, has increased sharply in recent years on account of the effects of inflation.

There is a growing gap between the picture painted by the national accounting statistics and households’ subjective perceptions of what is happening to their personal finances, despite the fact that they tend to move in tandem (Miyar, 2023). To understand these differences it is necessary to better understand citizens’ perceptions and experiences. One way of doing this is via opinion surveys. With that goal in mind, in May 2025, Funcas carried out the Economy and Household Finances Survey, using a representative sample of 1,200 people, the results of which are outlined in the next section of this paper.

Respondents’ perception of the national economy and their household finances

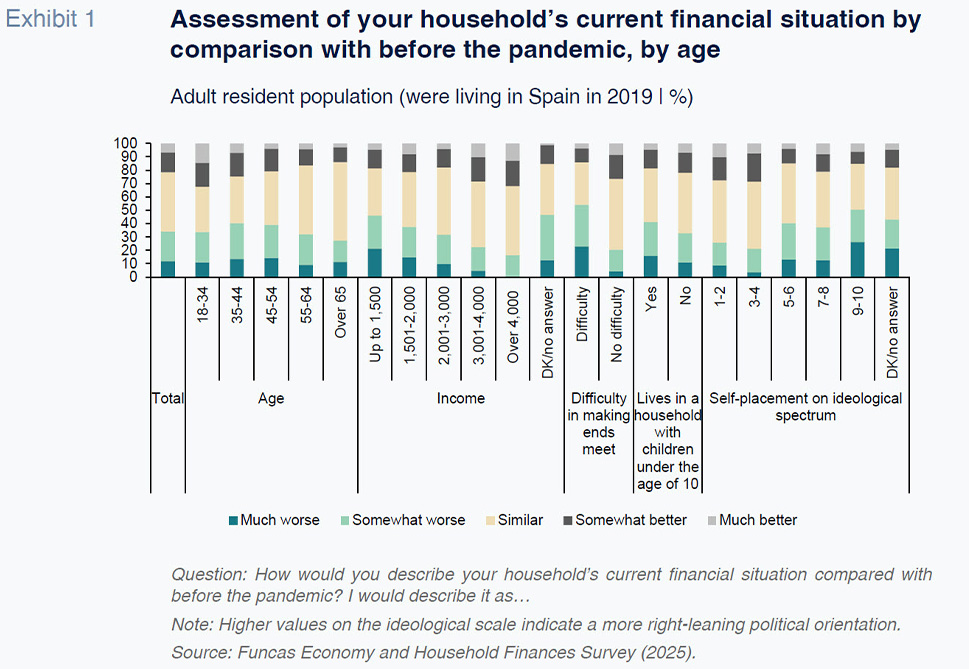

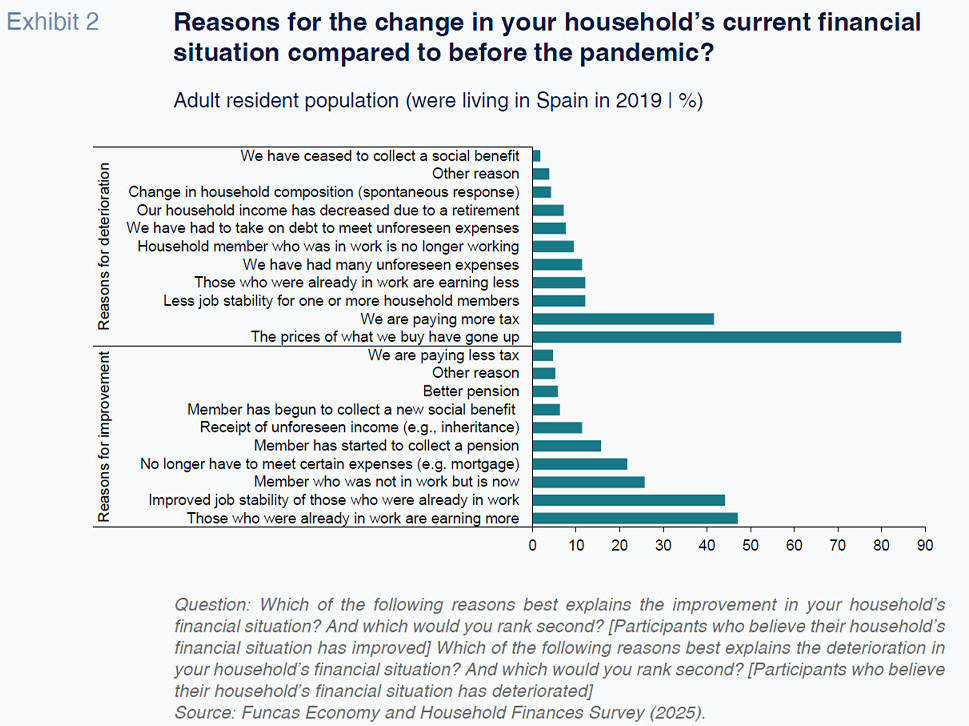

The survey asks the participants (who had to be already living in Spain in 2019) to compare their households’ financial situation today with that of before the pandemic. Nearly half of the people surveyed answered that their household financial situation was similar today to before the health crisis (44%). However, 34% believe it has deteriorated, which is considerably more than the 22% who believe it has improved (Exhibit 1). As for the two main causes of the perceived trend, among those reporting an improved financial situation, the explanations are predominantly personal or family-related. Nearly half of them mentioned higher wages for household members who were already in work before the pandemic (47%), while the second most common reason was improved job stability (44%) (Exhibit 2). They also frequently mentioned the employment of household members who were not previously working (26%) and a reduction in certain household expenses (22%). Other reasons cited include the collection of a pension (16%), unforeseen income (11%), the receipt of a social benefit for the first time (6%) and pension increases (6%). In general, we are talking about factors related with changes in household finances rather than structural dynamics. In contrast, those reporting a worse financial situation tended to signal external and general factors (Exhibit 2). The reason cited the most, by a wide margin, was inflation (85%), followed by higher taxes (42%). At a distance lie other more specific reasons such as reduced job stability (12%), lower wages (12%), unforeseen expenses (11%), the loss of a job (9%) and retirement (7%).

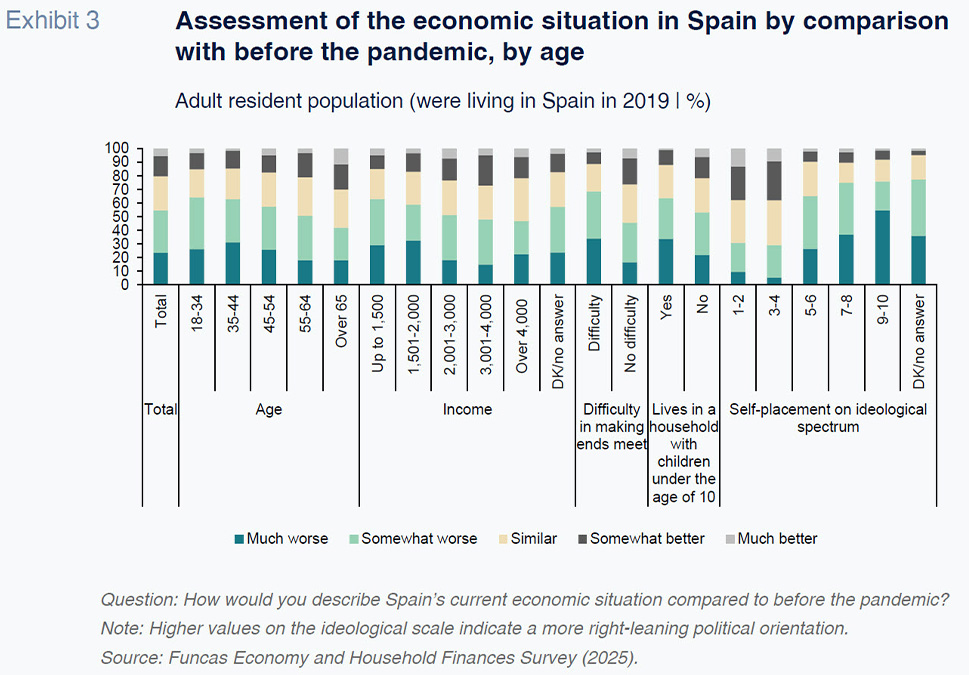

As for their assessment of the Spanish economy as a whole, the overall perception is remarkably negative, more so even than their assessment of their household finances. Specifically, over half of those surveyed (55%) consider that the Spanish economy has deteriorated since 2019: 24% said it was “much worse” and 31% described it as “somewhat worse”. Just 25% believe the economic situation is similar and 20% believe it has improved (Exhibit 3). This contrast,

i.e., a relatively more benign assessment of personal situations relative to the general economic situation is common in public opinion polls, including the CIS barometers in Spain and other surveys conducted by Funcas in the past. It can be interpreted as the result of a cognitive process in which, when assessing the state of the country, individuals consider, in addition their immediate experiences, broader and more diverse aspects of the social and economic reality. It suggests that citizens are sensitive to collective problems beyond those that affect them directly.

It is important to ascertain to what extent the perceptions expressed by the respondents are shaped by differences in wellbeing and material living conditions as opposed to subjective factors, such as ideological positioning, for example. In light of the data collected, both dynamics play a relevant role. One the one hand, certain socio-demographic characteristics related with the cycle of life and material living conditions are systematically linked (and positively correlated) with the assessment of various economic dimensions. Differences in age, in household composition, in income levels and in the ability to make ends meet are significant factors. For example, people aged between 35 and 54, followed by the youngest cohort (18 to 34 years of age) tend to express the highest levels of dissatisfaction. Nearly four out of every 10 people aged between 35 and 54 said their financial situation had worsened, which is a little more than the percentage of young people making the same claim (34%) and considerably more than the shares of people close to retirement (32%) or already retired (27%) reporting a deterioration (Exhibit 1).

A majority of those under the age of 45 also expressed a negative assessment of the overall economic performance, almost two-thirds in fact. This percentage trends lower as age increases (Exhibit 3). A negative assessment is also more common among those reporting lower household income and difficulties in making ends meet. Note, lastly, that households with young children are systematically the most negative about their household situation and the economy in general, reflecting the additional difficulties encountered by families during their child-rearing years.

Elsewhere, the role played by ideological positioning also comes into play in these assessments. Among people who identify more along the left of the ideological spectrum, the percentages reporting an improvement or deterioration in their financial situation are more or less balanced. In fact, in the centre-left segment, positive perceptions slightly outweigh negative perceptions; this is the only segment where this is the case (Exhibit 1). In contrast, from the centre to the right, negative perceptions clearly dominate, with a much higher percentage of respondents reporting a perceived deterioration in their financial situation than those who perceived an improvement. The difference is at its highest the furthest to the right, where 50% report a perceived deterioration and just 15% cite an improvement.

These differences are even more pronounced in relation to the perceived trend in the country’s economic performance compared to before the pandemic. Further to the left, positive assessments outweigh negative perceptions: 38% believe the economy has improved, compared to 30% who feel it has worsened (Exhibit 3). However, from the centre to the right, this situation clearly reverses: in ideological positions 5-6, 65% report that the economic situation has deteriorated, while in positions 9-10, the percentage increases to 76%.

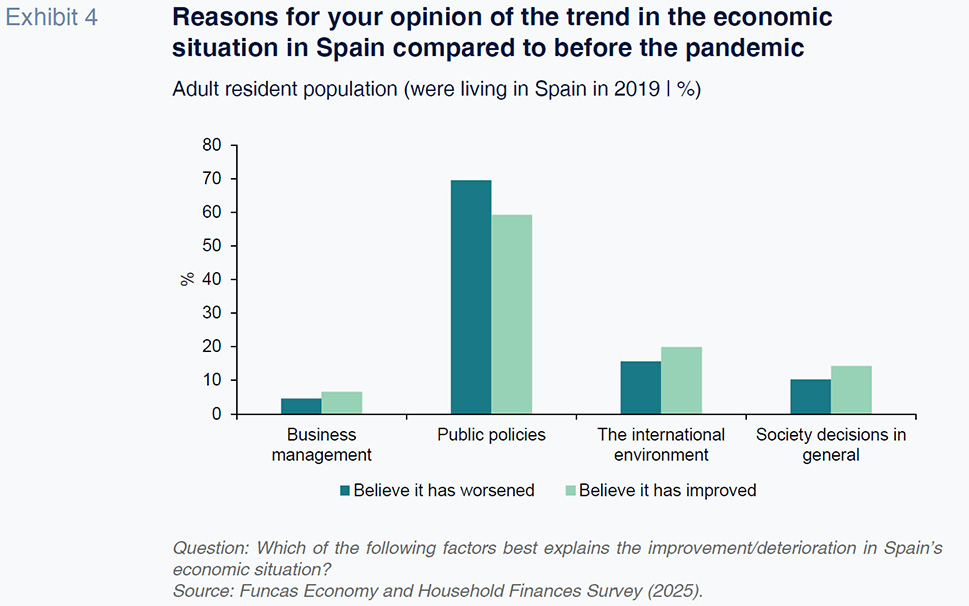

The role played by political polarisation in assessing the economy becomes clear when the participants were asked about the reasons for their perception of the trend in Spain’s economic situation. Among both those who believe the situation has worsened and those who perceive an improvement, the majority attributes the economic performance primarily to public policies (Exhibit 4). More specifically, among those signalling a perceived deterioration, 70% cited political decisions as the main cause, very significantly above other factors such as the international context (16%), society decisions (10%) or business management (5%). Meanwhile, a majority of those reporting an improvement also cite public policies (59%), albeit giving a little more weight to the international environment (20%), society decisions (14%) and business management (7%).

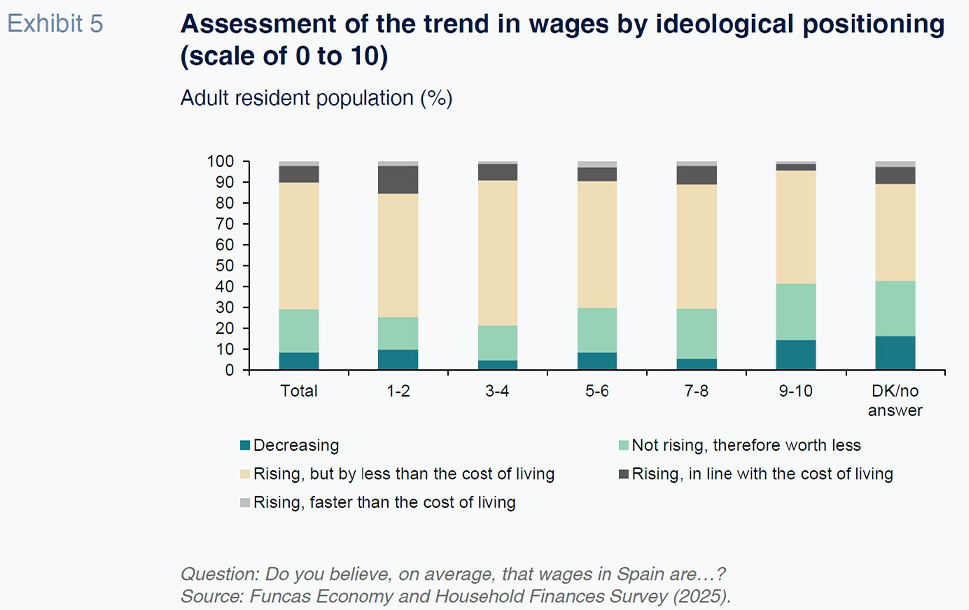

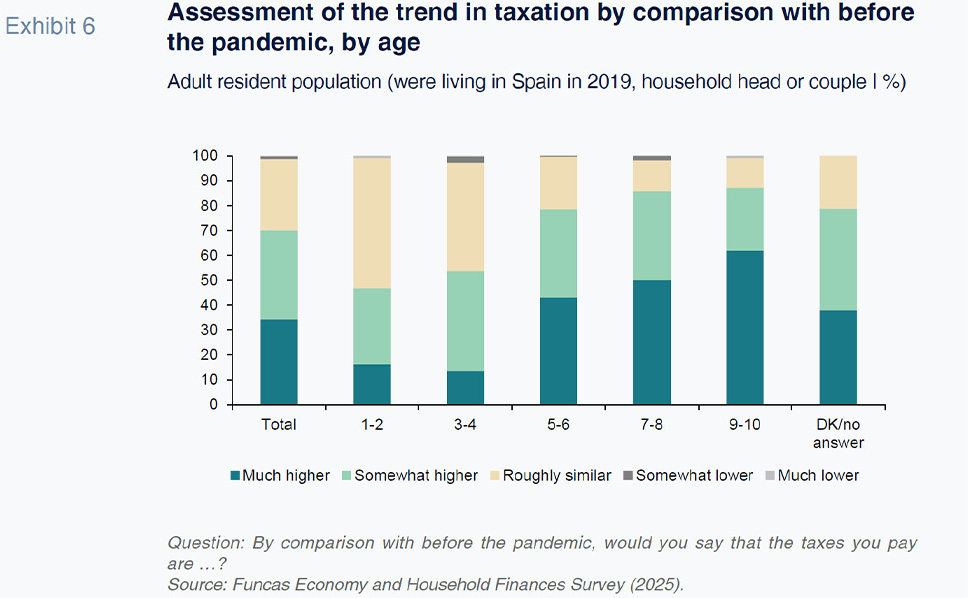

However, one dimension sparked consensus among the survey participants, namely the widespread perception of impaired purchasing power. This consensus is apparent in another two indicators yielded by the survey. Ninety per cent of those polled said their wages had lost purchasing power, either because they had not increased or had increased by less than prices (Exhibit 5). Unlike other perceptions expressed, here there is barely any variation by ideological positioning, reinforcing the idea that the loss of purchasing power constitutes a widely shared experience. In addition, as analysed in the next section, 70% reported that taxes had increased since the pandemic. Here, however, we do see considerable differences by political positioning: this perception is less common among people who identify more with the left and clearly increases as we move to the centre and right of the ideological spectrum (Exhibit 6).

Receipts from the main taxes borne by households – personal income tax, VAT and excise duty – increased by €62.3 billion between 2019 and 2024 (AEAT, 2024). Over half of that increase (56%) was driven by personal income tax and another third (28%) by VAT, these being the two taxes households are most familiar with. For this reason, households perceive that the increase in the burden implied by these two taxes are key factors in their financial situation.

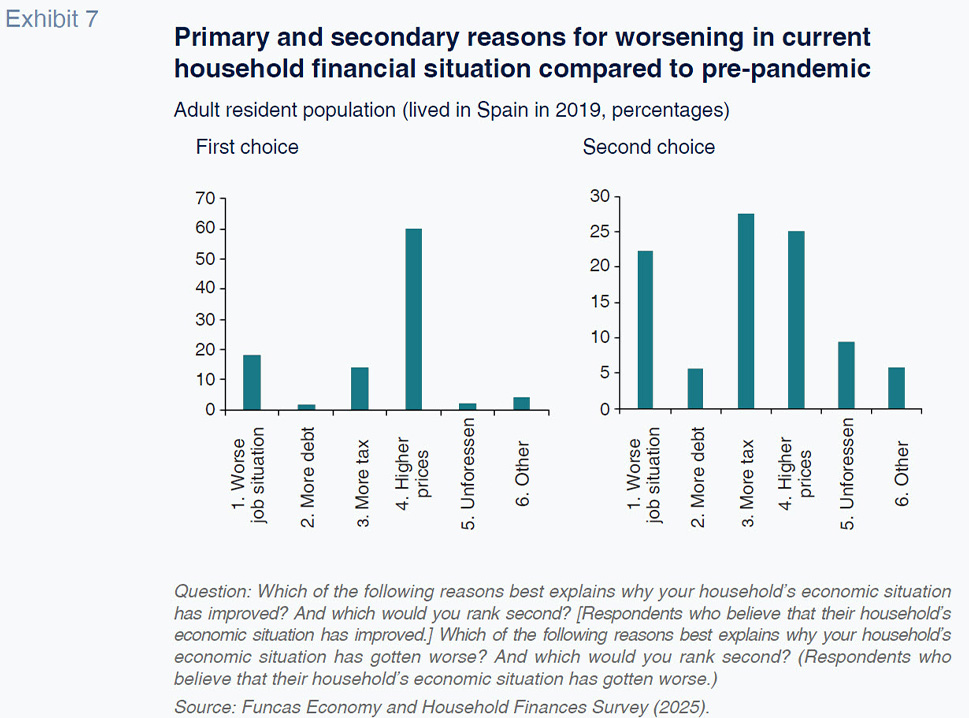

Roughly 70% of the people surveyed said that the main reason for their improved financial position was higher income associated with their job situation. The perceived impact of taxation for this cohort is very low: just 2% cited a lower tax burden as the reason for the improvement. To the contrary, the role of taxation for those reporting a deteriorated financial situation was far more significant. Exhibits 7 illustrate the causes of the deterioration, differentiating between the primary and secondary causes given. Sixty per cent selected consumer price inflation as the primary cause of the deterioration, followed at a considerable distance by a worse job situation associated with lower income (18%) or higher taxes (14%). As their second cause, more chose the increased tax burden (28%) than any other cause, albeit closely followed by inflation (25%) and a worse job situation (22%). In other words, the linkage between higher prices, lower real wages and a higher tax burden largely explains citizens’ negative perception of the economy.

In fact, one out of every three survey participants said their personal financial situation had worsened by comparison with 2019. This personal sensation matches the objective data tracking the trend in real average household income and the household tax burden (higher personal income tax and VAT burden). Funcas has recently published several studies corroborating this perception. Specifically, net real household income was 4.3% lower in 2024 than in 2008. In parallel, the average real personal income tax burden was 14.4% higher in 2024 than it was in 2008 (Romero-Jordán, 2025a, 2025b). Meanwhile, the VAT tax burden increased by an average €450 per household between 2021 and 2024 due to the effect of inflation (Romero-Jordán, 2025b). In sum, the subjective perception gleaned from the surveys is closely correlated with the objective underlying information.

The perception of a higher tax burden by age bracket has the shape of an upside down “U”. Specifically, 9% of those expressing this perception are under the age of 30, 30% are aged between 45 and 55 and around 20% are over the age of 65. This outcome makes sense in light of the differences in income levels and tax burdens by age cohort as household income tends to trend upward until the age of 55 to 60. However, it is the individuals with secondary school studies only who ascribe the highest weight to taxes in their negative perception of their financial situation: around 5 out of 10, compared to less than 3 out of 10 for individuals with university studies. This outcome is consistent with the idea put forward earlier that a negative perception of the economy is more common among those reporting lower household income and difficulties in making ends meet. This negative assessment is held by more than half of the participants in work (between 60% and 68%), which is significantly above the share of pensioners expressing a similar sentiment (around 18% to 20%). Lastly, the percentage of respondents who attribute their negative perception of the trend in their household finances to taxes is roughly three times higher among people who identify themselves as right-wing (positions 6 to 10 on the scale) compared to those to the left (positions 1 to 4).

References

AEAT. (2025).

Historical series tracking tax bases, rates and taxes accrued. https://sede.agenciatributaria.gob.es/Sede/datosabiertos/catalogo/hacienda/Informe_mensual_

de_Recaudacion_Tributaria.shtmlBANK OF SPAIN. (2025). An estimation of the contribution of the foreign population in Spain to GDP per capita growth in the period 2022-2024. Q2

Economic Bulletin.

EUROSTAT. (2025).

Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tessi190/default/table?dil=enCAIXABANK RESEARCH. (2024). The challenge of increasing the supply of affordable housing in Spain.

https://www.caixabankresearch.com/en/sectoral-analysis/real-estate/challenge-increasing-supply-affordable-housing-spainCAIXABANK RESEARCH. (2025). The transformative capacity of NGEU and other fiscal stimulus plans. Monthly Report | March 2025 | No. 498.

GARCÍA DÍAZ, M. Á., and PINTO HERNÁNDEZ, F. (2024).

Evolución de la ocupación y población activa en España 2019-2024. Detalle por comunidades autónomas [Trend in employment and active population in Spain, 2019-2024. Breakdown by region]. FEDEA.

INE. (2024).

Hotel occupancy survey, 2023.

INE. (2025).

Annual Salary Structure Survey. Year 2023. Final Data. Madrid: INE.

MIYAR-BUSTO, M. M. (2023). Juntos en los malos tiempos: la percepción social de la economía en España (2000-2023) [United in bad times: social perception of the Spanish economy (2000-2003).

Panorama Social, No. 37, 111-127.

ROMERO-JORDÁN, D. (2023). Impact of inflation in Spain in 2021 and 2022: Which households have been the hardest hit?

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 12, No. 3, 9-18.

ROMERO-JORDÁN, D. (2025a).

Impacto de la inflación sobre la factura de IVA de los hogares españoles en el período 2021-2024 [Impact of inflation on Spanish households’ VAT bills 2021 - 2024]. Investigaciones de Funcas.

https://www.funcas.es/documentos_trabajo/impacto-de-la-inflacion-sobre-la-factura-de-iva-de-los-hogares-espanoles-en-el-periodo-2021-2024/ROMERO-JORDÁN, D. (2025b). Estimating the impact of inflation on Spain’s tax burden: The hidden effects of fiscal drag.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 14, No. 2, 47-52.

https://www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Desiderio_14-2_1.pdf/

María Miyar. UNED and FUNCAS

Desiderio Romero-Jordán. Rey Juan Carlos University and Funcas