Bridging the financial literacy gap: Structural, cognitive, and situational disadvantage in adolescence

In recent years, adolescent financial literacy has gained prominence as a critical skill, yet large gaps persist across academic and socioeconomic cohorts, as well as across varying degrees of exposure to financial education. These disparities reflect deeper structural and educational inequalities, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions that equip all students for real-world financial decision-making.

Abstract: Despite widespread recognition of the importance of financial literacy, proficiency among adolescents remains uneven across varying socioeconomic and educational contexts. A typological framework helps clarify these disparities by distinguishing between cognitive disadvantages, structural disadvantages, and situational disadvantages that shape financial literacy outcomes among 15-year-olds. Drawing on international PISA data and a novel classification of risk factors, allows for the quantification of the independent and cumulative impact of each type of disadvantage on student performance. Cognitive deficits in math and reading are the strongest predictors of poor financial outcomes, followed by socioeconomic background and lack of exposure to financial concepts in school or at home. Importantly, research highlights the high modifiability of situational disadvantage through targeted educational interventions, while also drawing attention to the necessity of strong foundational skills in math and reading to combat cognitive disadvantages. Schools can play a pivotal role in leveling the playing field by integrating financial education into the core curriculum and improving instruction in the basic academic skills necessary for financial literacy, combining educational reform with broader social equity goals to prepare all adolescents for the financial demands of adult life.

Adolescent financial education: Importance and existing gaps

The transition to adulthood exposes young people to complex financial decisions – from managing savings and student debt to choosing banking products – so lack of financial literacy can have adverse consequences. Previous research has found that adults with low financial literacy are more likely to make costly mistakes (e.g., taking on too much debt or failing to plan for retirement) and accumulate less wealth over their lifetime. Recognizing this problem, many countries have implemented financial education courses in secondary schools to better prepare adolescents for the real economic world.

Despite these efforts, significant gaps persist in the level of financial literacy among young people. PISA assessments show that while some students demonstrate strength in concepts such as budgeting, interest or inflation, a considerable proportion do not reach even the basic level of financial competence. These differences in performance are often closely linked to the student’s circumstances: their overall academic performance, their family and socioeconomic background, and the specific educational experiences to which they have been exposed. Historically, each of these factors has been studied separately. For example, the OECD has consistently highlighted the influence of socioeconomic status and parental education on students’ financial competencies, as well as the importance of math skills as a direct determinant of financial literacy. However, understanding the problem holistically requires considering how these different axes of disadvantage intertwine and reinforce each other.

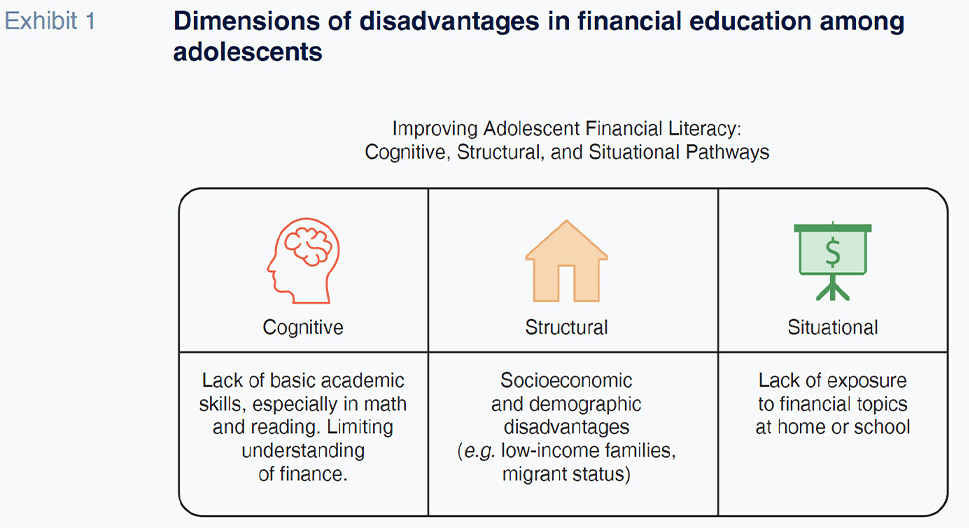

The study Mapping Disadvantage in Adolescent Financial Literacy (extended version of this summary) addresses this need by mapping disadvantage factors typologically. Rather than simply including control variables in isolation, it constructs a unified conceptual framework that groups sources of inequality into three main categories. Below, we describe each type of disadvantage and how it contributes to the observed gaps in financial literacy among adolescents.

Typology of disadvantages affecting financial education

Cognitive disadvantage: This refers to deficits in fundamental academic skills, particularly in mathematics and reading comprehension. In practice, this encompasses students with general underachievement in core subjects, which often translates into difficulties in performing arithmetic calculations, understanding percentages or interpreting texts – all essential skills for understanding financial concepts. The logic is straightforward: if a teenager has trouble with fractions or reading comprehension, he or she is also likely to struggle to understand compound interest on a loan, read a bank statement or compare investment options. Cognitive disadvantage thus encapsulates a lack of the basic intellectual tools needed to process financial information.

Structural disadvantage: This category encompasses adverse socioeconomic and demographic conditions that may limit financial learning. Typically, it encompasses students from low-income households, with limited parental educational attainment, or from a migrant/minority background. These structural factors often involve fewer material resources (e.g., no computer or Internet access at home), less educational support or encouragement from the environment (parents with long working hours or less familiarity with the financial system), and even lower academic expectations in the community. All this creates less fertile ground for the development of financial education. In other words, structural disadvantage reflects disparities of origin: these are obstacles linked to the student´s socio-familial environment, beyond his or her personal aptitudes.

Situational disadvantage: This refers to the lack of opportunities or formative experiences in financial topics in the young person’s daily environment. This is neither cognitive ability nor socioeconomic context, but rather exposure (or lack thereof) to financial education in daily life. For example, this category includes students whose parents do not usually talk about money or finances at home, who do not manage a personal budget (even if it is managing a weekly allowance) or who attend schools where no subject or workshop on finances is taught. A situationally disadvantaged teenager may have solid academic skills and come from an affluent family, but if they have never had the opportunity to become familiar with concepts such as savings, credit or the value of money, they will face a significant gap in their financial literacy. The key to this disadvantage is that it involves a lack of practical or contextual learning: the student has not “lived” situations that teach him or her, even in a basic way, how to manage money. The good news is that, unlike the other categories, this gap is more easily remedied through specific educational interventions (such as courses, financial games, home education programs, etc.), since it does not stem from intrinsic limitations of the student or from long-term socioeconomic disadvantages. Simply put, it is an experience gap, not an ability gap, and can therefore be closed by providing that missing experience.

These three dimensions –cognitive, structural and situational–, which are summarized in Exhibit 1, are not exclusive, but offer a way of organizing and understanding the different causes of low financial literacy. The same student may face one, two or all three disadvantages simultaneously. For example, let us imagine a 15-year-old migrant student attending a school in a vulnerable area: if she is also behind in mathematics and has never received financial education, she would be going through all three forms of disadvantage at the same time. On the other hand, another student could have a high academic performance and come from a well-to-do family (without cognitive or structural disadvantage), but if his school does not offer financial content and his home does not talk about the subject, then he would only present situational disadvantage. The value of this typology is that it allows us to diagnose more precisely who is disadvantaged and what is they type of disadvantage, which is very useful for designing solutions tailored to each need.

How much do these disadvantages influence financial education performance?

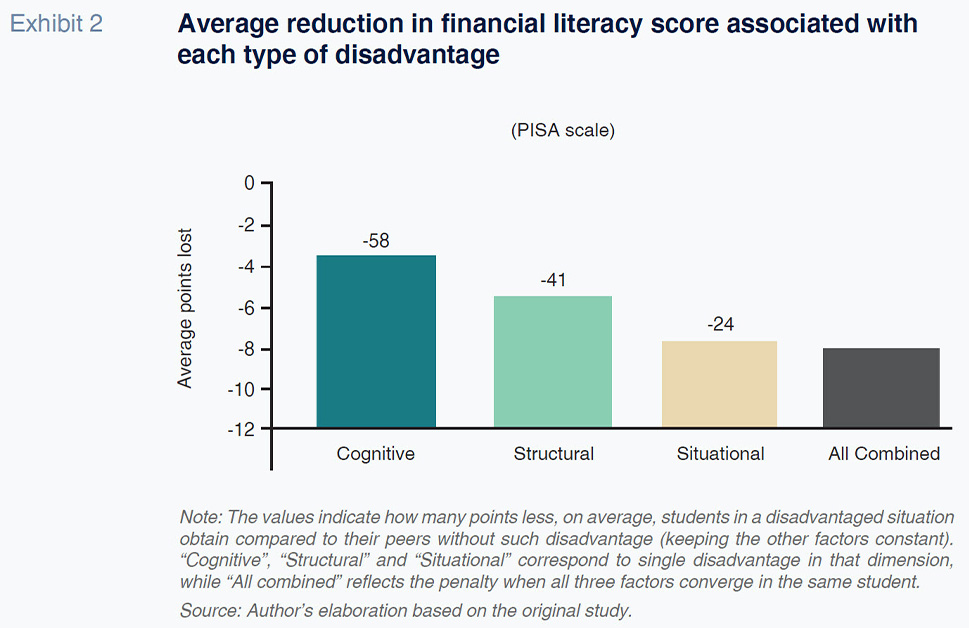

A key question is to determine the extent to which each type of disadvantage affects financial literacy outcomes. The study quantifies these impacts using PISA data: by isolating each factor, it is possible to estimate how many financial literacy score points are “lost” on average when a student is disadvantaged compared to his or her peers without such disadvantage. The findings indicate that all disadvantage pathways lead to significant penalties in financial performance, albeit with different magnitudes.

- Impact of cognitive disadvantage: This is the single most influential factor. A student with well below-average math and reading skills tends to score markedly lower on the financial test. On average, the penalty associated with cognitive disadvantage is around -58 PISA points (i.e., 58 points lower) on the financial literacy scale compared to an average student. This drop is equivalent to more than half a PISA proficiency level, reflecting the weight of not having the basic skills to process numerical and textual information in financial contexts.

- Impact of structural disadvantage: This is also considerable, although somewhat less than cognitive disadvantage. Belonging to a disadvantaged socioeconomic background is associated, on average, with about 41 points lower in the financial literacy score, compared to students from a more advantaged position. This effect suggests that accumulated shortcomings (fewer educational resources at home, less parental support, possible lower quality school environments, etc.) take their toll on the financial knowledge that young people manage to acquire. It is worth noting that much of the structural disadvantage may manifest itself indirectly through cognitive disadvantage (for example, a student of low socioeconomic status may perform worse in mathematics because of these shortcomings). Yet, even at equal levels of academic ability, socioeconomic background still makes an appreciable difference in financial literacy outcomes. This indicates that there are environmental factors (such as attitudes towards money, financial stress at home, less access to banking services, etc.) that hinder the financial learning of low-income youth beyond their school performance.

- Impact of situational disadvantage: Although this form of disadvantage might seem less “severe” than the previous ones, its effect is not negligible. Lack of exposure to financial education, either in school or in the home environment, is linked to approximately 24 points lower on average in financial performance on PISA than those who did have some training or practical experience. Put another way, a teenager who has never learned about basic economic concepts tends to fall behind those who did have the opportunity to become familiar with them in classes or everyday conversations. While ~24 points seems like a smaller gap compared to the cognitive and structural disadvantages, it still represents a significant difference equivalent to several months of learning. In addition, it is important to remember that situational disadvantage often co-exists with the others: for example, students from low-income families (structural disadvantage) are often the ones who do not receive financial education at their school (exacerbating situational disadvantage), which together amplifies the negative impact.

As Exhibit 2 illustrates, each type of disadvantage acts as a drag on financial performance. The gap linked to a single dimension can range from 20 to 60 PISA points, but when a student suffers several disadvantages at once, the cumulative drop in his or her score can approach 100 points. On the PISA scale (where the average is usually around 500 points), a difference of 100 points is roughly equivalent to almost two standard deviations of performance, or in other words, the distance between an outstanding student and one who is lagging far behind. This data show the extreme vulnerability of those who face multiple disadvantages: they are young people who, without intervention, are at serious risk of being excluded from the basic financial literacy necessary for adult life.

A particularly encouraging finding of the study is the evidence that school-based financial education can counteract some of these gaps. Those students who have taken at least one finance subject or workshop in school perform significantly better than similar students who did not study such a subject. In estimated terms, the advantage associated with receiving formal financial instruction is of the order of +30 PISA points in financial education. This positive effect more than offsets the average situational disadvantage of -24 points mentioned above. In other words, offering financial education in the classroom can level the playing field for those who would otherwise have no exposure to the financial world. It is worth noting that this Exhibit comes from statistical comparisons controlled for other factors (it is not a randomized experiment); still, it strongly suggests that school does make a real difference in students’ financial literacy.

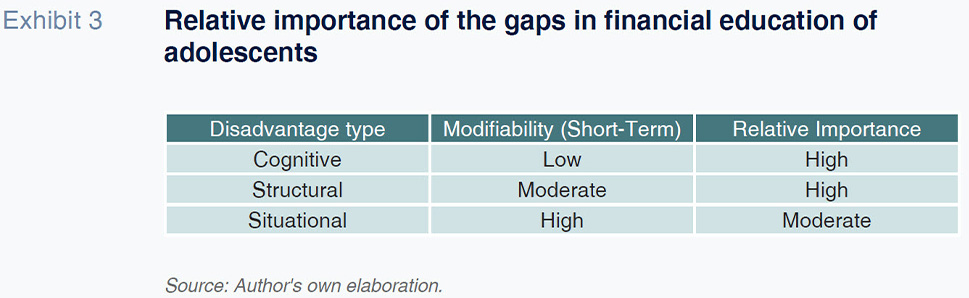

It is important to note that not all gaps are equally easy to close (see Exhibit 3). Cognitive disadvantage, for example, is linked to skills gaps that develop over many years (starting in primary education) and therefore has no immediate solution beyond continuing to improve the overall quality of education. Similarly, structural disadvantage reflects deep-rooted social inequalities, the reduction of which requires broad and long-term policies. Situational disadvantage, on the other hand, can be addressed more directly and quickly through targeted educational policies-primarily by incorporating financial education in schools on an equitable basis. This difference in “modifiability” was explicitly recognized in the study, which categorized cognitive disadvantage as low modifiability in the short term, structural disadvantage as moderate modifiability and situational disadvantage as high modifiability, given the possibility of introducing specific educational interventions.

In short, financial education gaps are due to multiple interrelated causes. The typological approach allows us to understand that there is no single way to reduce them: it is necessary to act on the set of factors that place certain students at a disadvantage compared to others. The main recommendations derived from these findings, aimed at informing public policies in the educational and social spheres, are presented below.

Implications for education and economic policy

The results of the study have relevance both for educational policy (what and how is taught in schools) and for broader socioeconomic policy (how to reduce the gaps of origin that influence learning). From the mapping of disadvantages, key lessons emerge:

- Financial education in schools is fundamental and should be expanded. Given the clear beneficial effect of formal financial instruction, a central recommendation is to integrate financial education into the compulsory secondary school curriculum (and even from basic levels, adapted to each age group). This would ensure that all young people acquire at least basic notions regardless of their family background. Evidence suggests that when the school offers this knowledge, the educational gap of those who do not obtain it at home is mitigated, significantly reducing the situational disadvantage. To maximize impact, these educational programs should be practical and attractive, connecting financial theory with real-life situations that adolescents can understand (managing a monthly budget, responsible use of credit cards, evaluation of telephone offers, etc.). It is also valuable to involve the community and families: for example, through assignments or projects that invite students to discuss finances with their parents, thus encouraging learning at home as well.

- Don’t neglect basic skills. Investing in cognitive skills is investing in financial education. Educational leaders must recognize that improving math and reading instruction is not only an academic end in itself, but has a positive spillover effect on students’ financial readiness. A strong numeracy and reading base empower young people to understand increasingly complex financial information. Therefore, policies such as strengthening the level of teaching in mathematics (e.g., teacher training, updating teaching methods, support classes for students with difficulties) and promoting reading comprehension (e.g., through readings applied to everyday contexts, including simple economic texts) should be an integral part of the strategy. This point also suggests that financial education should not be seen as an isolated content, but can be integrated transversally, taking advantage of mathematics classes (exercises with interest rates, expenditure statistics) and language classes (comprehension of basic economic items, financial vocabulary) to reinforce both types of literacy at the same time.

- Comprehensive approach and intersectoral coordination. The above lines of action should not be seen in isolation, but as complementary pieces of the same strategy. The study emphasizes that addressing the youth financial education gap requires a multisectoral approach. Schools alone can achieve a lot – indeed, they are key players in matching experiences – but they also need the support of broader economic and social policies. Ideally, ministries of education, central banks, consumer protection agencies and others should collaborate on national financial education programs that incorporate curricular improvements, teacher training, quality teaching materials, awareness campaigns for parents and youth, and ongoing evaluation of results. At the same time, financial inclusion initiatives (such as savings accounts for children, conditional scholarship programs, etc.) can be complemented with education to ensure that young people know how to take advantage of them. In short, the idea is to create an educational and social ecosystem in which every adolescent, regardless of his or her context, can acquire the financial knowledge and habits needed to succeed.

Conclusions

Financial literacy in adolescence is much more than a test score; it is a pillar for future economic autonomy and, many experts argue, a form of citizenship in the 21st century. Analysis of the cognitive, structural and situational pathways of disadvantage teaches us that disparities in such literacy do not have a single cause, and therefore there is no simple solution. On the contrary, it requires a sustained commitment from multiple fronts: the educational system, social policies and family involvement.

A central lesson of the study is that schools can and should be agents of change to reduce gaps. Not just by imparting financial literacy, but by supplying the experiences that some students do not get at home-for example, through hands-on projects or simulations that bring young people into the real world of money in a guided and safe way. In this way, the school becomes an institution capable of “bridging” contextual differences and providing all students with a more equitable starting point.

At the same time, we must recognize that the financial performance of adolescents reflects to a large extent the broader inequities in our society. Improving financial literacy is therefore also a matter of educational justice and long-term social investment. Financially competent young people will make better economic decisions, avoid over-indebtedness traps, take advantage of investment or entrepreneurship opportunities, and contribute to a healthier economy. But for these benefits to reach everyone, we must start by closing the learning gap that separates different groups of students early on.

In conclusion, the study’s mapping of disadvantage provides a valuable roadmap for action: it helps us diagnose the roots of inequality in financial literacy and guides the design of interventions according to need. By following this roadmap, policymakers and educators can implement targeted and effective strategies – from strengthening basic skills in elementary school to ensuring that financial education reaches far and wide, to providing more support to those facing difficult contexts. Only by addressing the cognitive, structural and situational pathways together will we ensure that the next generation of citizens is better prepared for the financial challenges of tomorrow, narrowing today’s gaps and moving toward greater economic and social equity.

Financial and Digitalization Research, Funcas