Changes in European financial and monetary conditions: Summer 2018

Despite the ECB’s recent decision to prioritize the end of QE, while delaying rate hikes, EU banks may still see an improvement in net interest margins from the normalisation of yield curves. Nonetheless, although the European financial sector is better off today than before the crisis, it remains vulnerable to potential shocks from US protectionism and instability in Italy.

Abstract: As the conditions that unleased the 2012 sovereign debt crisis normalise, European financial markets too have stabilised. As a result, the eurozone is facing a shift in monetary policy conditions as the ECB recently signalled that it would end its historic bond-buying program next year and that interest rates would likely rise in late summer 2019. Despite the ECB’s decision to prioritise the end of QE, while delaying rate hikes, banks could still benefit through the normalisation of yield curves. However, the financial sector continues to face risks including hostile US trade policies and solvency concerns in Italy. These factors could delay the implementation of the ECB’s policy decisions, even though the eurozone banking sector is now less vulnerable to negative shocks. Specifically, recent data show that the link between sovereign and bank risk has eased significantly in recent years and that eurozone banks have reduced their cross-border exposures, particularly to Italy.

Financial stability in Europe: Situation and outlook

Summer has brought change as well as sporadic episodes of stress to the European banking sector. Although Europe’s financial system remains stable, events that signal a divergence from the European Central Bank’s (ECB) prevailing monetary policy warrant close attention. The most significant of these is the end of the ECB’s quantitative easing (QE) programme. To the surprise of financial markets, the ECB announced on June 14th a shift in its monetary policy by moving up the anticipated end date for its asset purchase programme to December 2018. The ECB also provided financial markets with forward guidance regarding future interest rate hikes. While no specific date was given for the next interest rate adjustment, the ECB did say that it expected to raise rates next summer. Analysts now believe the first rate increase will be announced in September 2019.

In this article, we analyse the ECB’s recent policy announcements and their potential impact on the financial sector. We will also examine indicators relating to the profitability, efficiency and solvency of the European banking sector ahead of these policy changes.

It should be noted that the latter part of the spring has been dominated by political developments, such as the formation of new governments in Spain and Italy. The latter has caused particular concern given the protracted negotiations over the configuration of Italy’s new cabinet and the widespread belief that the governing coalition lacks the necessary commitment to fiscal discipline and the preservation of the euro. In this paper, we analyse the impact that Italy’s political situation will have on European financial stability. Italy is the eurozone’s third largest economy and its high levels of public and private debt could have a destabilizing impact on European financial markets.

From a macroeconomic standpoint, it is impossible to ignore the consequences associated with the US government’s decision to impose substantial tariffs on aluminium and steel products. Ostensibly, these tariffs were meant to target China, but their reach has expanded to include allies, such as Canada, Mexico and the EU. This policy has been identified by the ECB as the main international risk to the eurozone’s economy, with the political situation in Italy viewed as the greatest source of regional vulnerability.

Regardless of how these events play out, the key supervisory authorities do not believe that financial stability is at stake. The ECB published a new edition of its Financial Stability Review in May, in which it highlights the absence of excessive credit growth and the robustness of Europe’s banks. Nevertheless, the ECB did flag an acceleration of risk-taking behaviour in several markets with “pockets of stretched valuations in certain segments”. As well, the ECB drew attention to the risk of spill-overs from the possible re-pricing of certain assets (mainly in the bond markets) and concerns about public and private debt sustainability levels in certain eurozone member states.

Notably, the ECB presented two new indicators for gauging near and medium-term risks to eurozone’s financial stability. The first is a composite financial stability risk index (FSRI) aimed at predicting large adverse shocks to the real economy in the near term. The second is a composite cyclical systemic risk indicator (CSRI) designed to identify the risk of a financial crisis over the medium term

[1]. In the

Financial Stability Review, the ECB mentions that both indicators have “fluctuated at low levels in recent quarters, implying a low likelihood of systemic risks to the euro area materialising in the near-to-medium term”, while still noting that recent readings have increased somewhat.

Monetary decisions and rate guidance: Spill-overs for the banks’ balance sheets

The ECB’s Governing Council met in Riga on June 14th and undertook, as outlined in its press release, “a careful review of the progress towards a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation, also taking into account the latest Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, measures of price and wage pressures, and uncertainties surrounding the inflation outlook.” The Governing Council announced the following decisions:

- It will continue to make net purchases under the asset purchase programme (APP) at the current monthly rate of 30 billion euros until the end of September 2018. After September 2018, “subject to incoming data confirming the Governing Council’s medium-term inflation outlook”, the monthly amount of the net asset purchases will be reduced to 15 billion euros until the end of December 2018. After that, net purchases will end.

- It intends to maintain its policy of re-investing the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP for an extended period of time after the APP ends, and “in any case for as long as necessary to maintain favourable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation”.

- The interest rate on the main re-financing operations, as well as the interest rates on the marginal lending facility and the deposit facility, will remain unchanged at 0.00%, 0.25% and -0.40% respectively.

- An important take-away from this meeting relates to timing of the ECB’s next interest rate hike. In its press release, it announced that it expects: “the key ECB interest rates to remain at their present levels at least through the summer of 2019.” The phrase, “through the summer of 2019” points to a likely rate increase towards the end of the summer rather than at the beginning, an interpretation reinforced by Mario Draghi when he alluded to “September 2019” during the press conference.

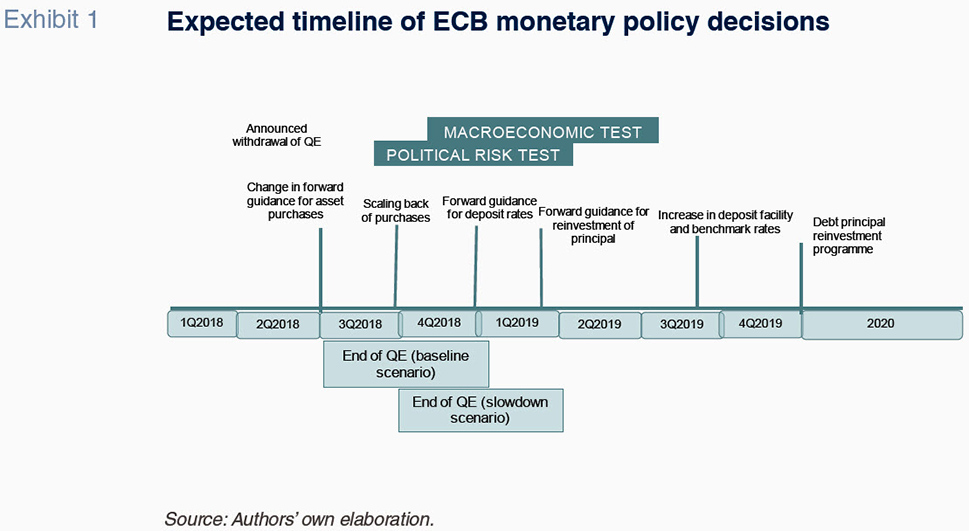

Exhibit 1 shows the expected timeline of ECB monetary policy decisions and those factors that might influence these decisions over the course of 2018 to 2020. It should be noted that these decisions are dependent upon inflation trends and economic stability. Consequently, between now and the end of the year, the ECB will be assessing how the markets respond to the announced reduction and subsequent termination of the bond-buying programme. Above all, the ECB will be monitoring how the supply of, and demand for, these bonds changes in the early months of 2019 once the ECB withdraws its support.

This essentially constitutes a dual test. Firstly, it is a political test for the eurozone given the fiscal uncertainty that could take hold in the absence of budgetary discipline and the necessary alignment by certain member states with the eurozone’s interests. On this point, Italy is the main source of concern for reasons explained earlier. Secondly, it will require tracking macroeconomic conditions. No major developments are expected on the inflation front, but given the current state of the energy markets, it is conceivable that inflation will remain close to the target rate of 2%, making it difficult to envision the ECB prolonging its QE programme. It is also worth considering the forecasted slowdown of the eurozone’s GDP growth and the downside risks posed by creeping protectionist policies. On the other hand, US growth and employment rates continue to exceed forecasts, suggesting that the Fed will carry on with its plan to raise interest rates. This puts pressure on the ECB to avoid deviating too far from investment and financing conditions in the US, especially while there is significant pressure on both the dollar and the euro.

In a scenario that could be described as “baseline”, the ECB is expected to stick with the announced timeline. It will end its bond-buying programme in December of this year and begin to increase key rates near the end of summer 2019. It is also anticipated that the ECB will fine-tune its forward guidance over the next two quarters. Finally, there is a good chance that the ECB will raise its marginal deposit facility rate first from its present rate of -0.40% to 0% in one hike.

However, if the economic slowdown quickens, it is possible that the ECB will prolong some of its stimulus measures and push back its rate hikes. That said, this is not expected to be significantly delayed beyond the initial deadline of summer 2019.

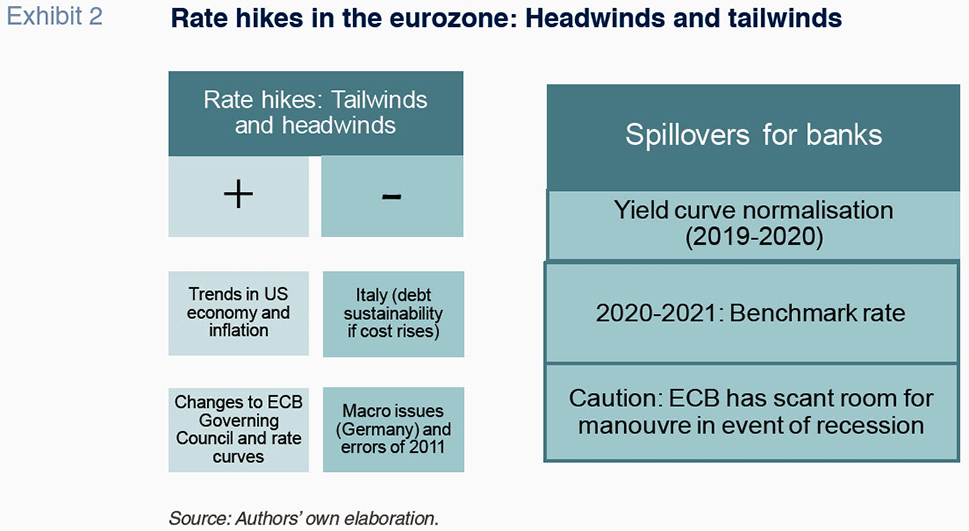

Exhibit 2 highlights some of the potential factors that might speed up or delay the ECB’s rate hikes. Firstly, the economic outlook for the US and the eurozone (despite the downward revision of forecasts) as well as expected inflation suggest rate increases are highly probable. Upcoming changes to the ECB’s Governing Council also support expectations of a rate hike. If, as many observers believe, the next ECB president comes from Northern Europe, this would further support the expectation of a rise in interest rates.

Nonetheless, specific country conditions could undermine plans for a rate hike. Working against an increase in the price of money is the situation in Italy. The concern is that if the average cost of borrowing rises above 4%, the country’s debt would become unsustainable under the government’s current fiscal plans. As well, slower growth in Germany and US protectionist measures could negatively impact the eurozone. The policy mistakes made in 2011 relating to both interest rates and the sovereign debt crisis could also have a latent negative impact on the region’s economy.

Ramifications for the banking sector

On the right-hand side of Exhibit 2, we summarise how an increase in benchmark rates could spill over to the eurozone banks’ balance sheets. It is worth noting the widely accepted notion – which may prove precipitous – that the accelerated withdrawal of QE and the pushback of rate increases could be bad news for the banks. This interpretation is based on the fact that the prevailing expectation prior to the ECB’s press conference on June 14th was that rates would begin to rise in June 2019. Subsequent forward guidance has now pushed back this deadline by a few months. However, it is possible that this delay will benefit the banks if it occurs under a more ‘normal’ monetary environment. Specifically, the withdrawal of QE may inject a degree of relative ‘normality’ into the sovereign bond yield curves. This ‘normalisation’ could then spill over into the corporate bond markets, steepening the yield curve and enabling the banks to carry out their liquidity transformation functions (borrowing over the short term and lending over the long term). As a result, banks would see their net interest margins rise.

In a recent article (see, Carbó and Rodríguez, 2018), we analysed the drivers of the return on equity (RoE) for a sample of 30 Spanish banks between 2008 and 2016. This estimation used panel data and fixed effects, with dummy annual variables in order to capture changes in demand over time. The explanatory variables included benchmark interest rates. Extending those estimates to 2017, we identified an interesting correlation between ECB interest rates and the banks’ RoE: A quarter-point increase in benchmark rates translated into an increase in the banks’ RoE between 0.8 and 1 percentage points. However, these estimates represent a general approximation. Each financial institution has its own level of sensitivity to ECB interest rate movements based on its assets and liabilities. Banks therefore make their own leverage and margin-generation adjustments as a result of this specific relationship.

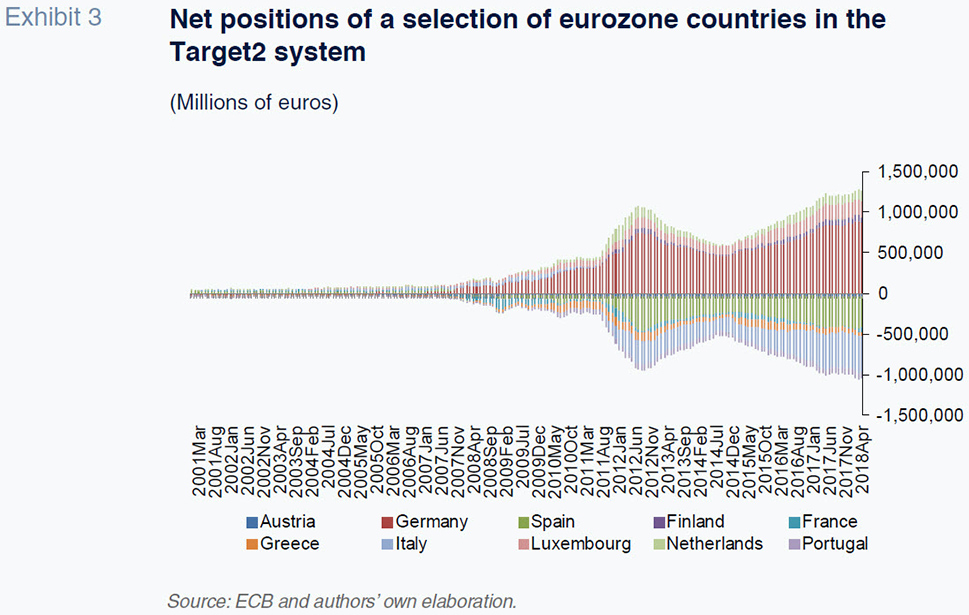

Looking at the eurozone as a whole, an important determinant of the banks’ ability to increase their leverage relates to their exposure to sovereign debt and the sovereign debt yield curve in each country. In this respect, it is worth highlighting the fact that we have been observing a significant change, particularly since the sovereign debt crisis of 2012, in the accounting records of the claims and liabilities of each eurozone member state, as reflected in the Target2 system. It is likely that the ECB is concerned that an interest rate hike could exacerbate Target2 imbalances. As shown in Exhibit 3, Germany’s position in Target2 is clearly positive with net claims of 900 billion euros. However, other countries, such as Spain and Italy, have a negative net position. Worryingly, Italy’s negative net position has exhibited a sharp rise. Certain preliminary estimates suggest that in May – after the timeline covered by the exhibit – Italy’s negative balance may have increased by 465 billion euros. More significantly, it is possible that Italians may have withdrawn 41 billion euros from their deposit and securities accounts and moved that money to other eurozone banks outside of Italy. Cross-border flows such as these would weaken the Italian banking sector, which is already suffering from poor asset quality and solvency concerns.

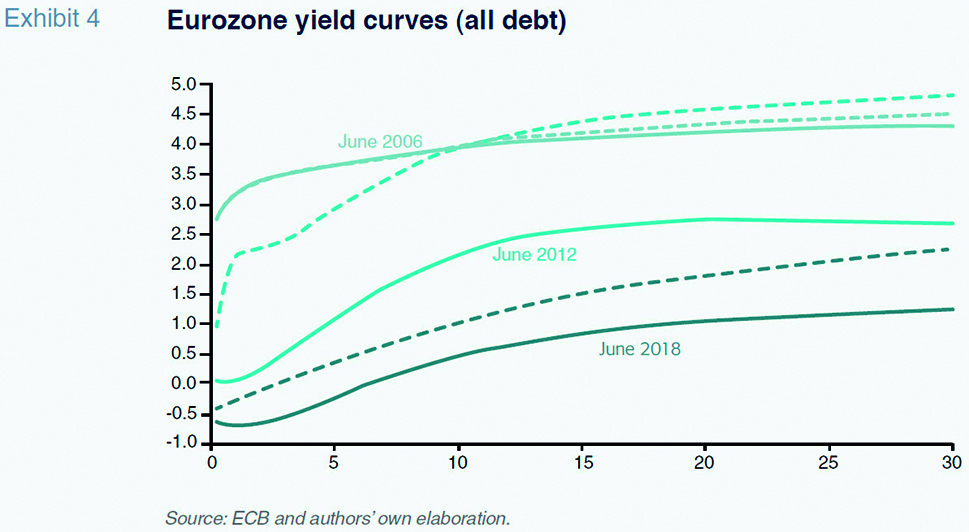

These developments also affect the risk implicit in the public debt yield curve in each of the eurozone’s member states. This constitutes the first and probably most important constraint for the specific yield curve faced by financial institutions in each country. At any rate, all European banks face monetary conditions that are impeding their ability to generate interest rate spreads due to the persistence of flat yield curves (very narrow range of returns over different time horizons). Exhibit 4 shows the average interest rate curve for the debt issued in the eurozone as a whole according to ECB estimates. It reveals how rates have been falling since 2006, with the curves steepening a little (albeit almost exclusively at the short and medium ends of the curve) during the crisis of 2012.

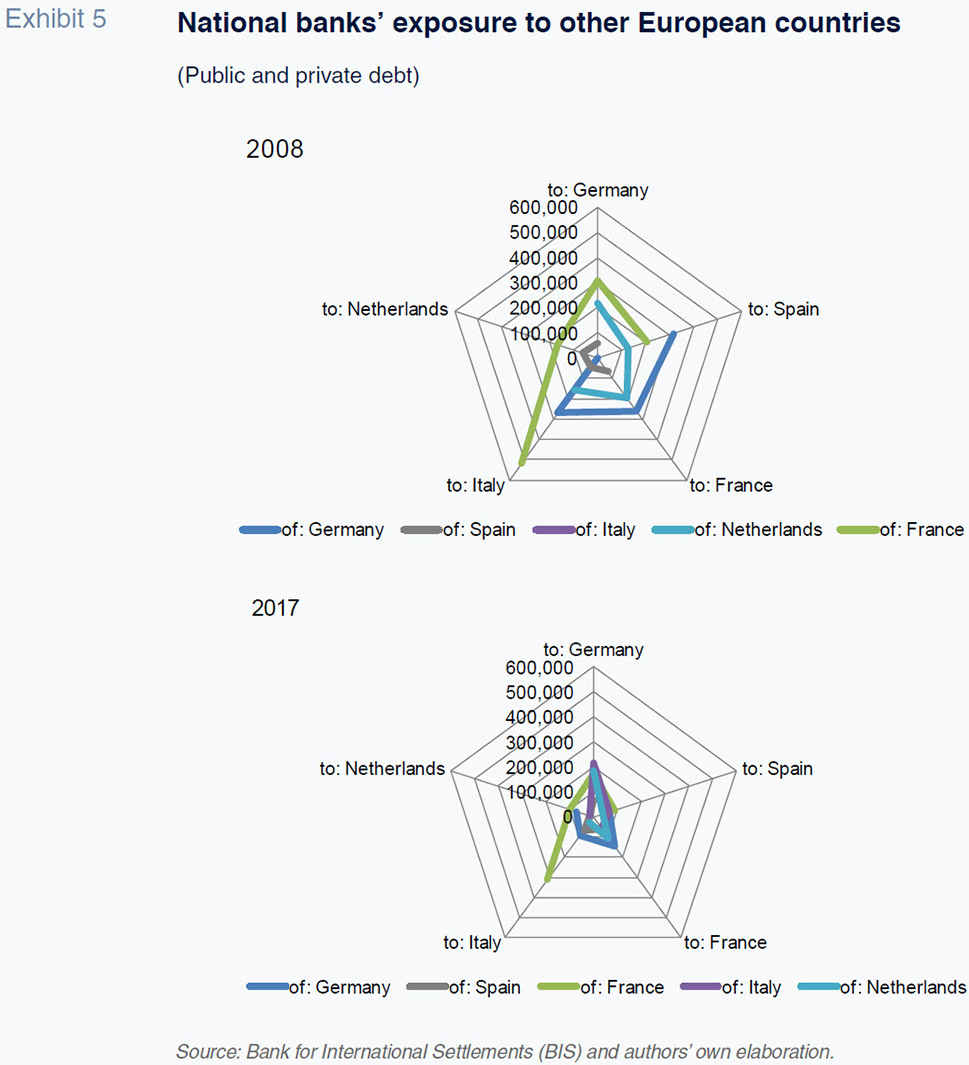

However, the risk of cross-border contagion has been reduced by the fact that the banks in each country have scaled back their exposure to the public and private debt issued by other countries. This is illustrated in Exhibit 5 by comparing figures presented by the Bank of International Settlements in Basel (BIS) from 2008 to 2017. The biggest reductions are observed in the exposures of the French and German banks to Italian debt.

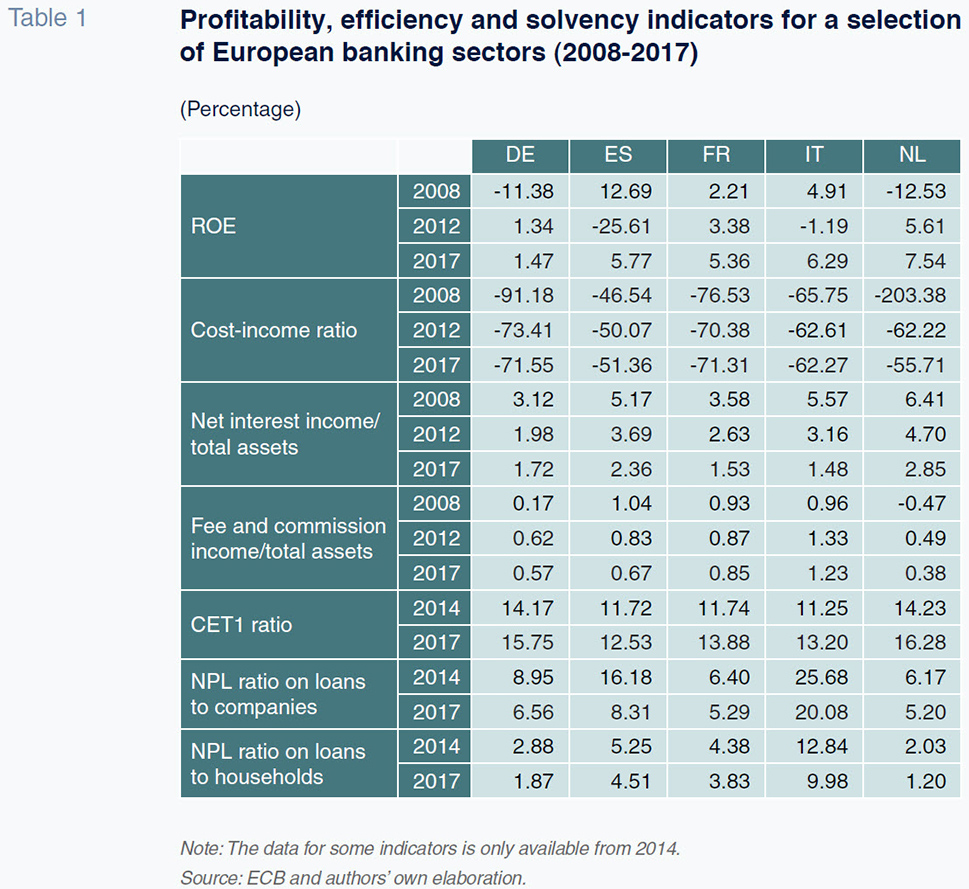

European bank performance and the outlook post-QEIt should be noted that the situation in summer 2018 in terms of the banks’ profitability, efficiency and solvency is not comparable with that of six years ago. The exception among the countries analysed (as shown in Table 1) is Italy, where certain indicators, particularly those related to asset non-performance, have deteriorated considerably.

Table 1 shows Germany with a relatively low RoE, a high level of solvency and with room for improvement in terms of cost efficiency. The financial crisis reached Spain later than other countries, with the profitability of its banking sector taking a particularly hard hit. However, by 2017 the banks had undergone a significant recovery. Particularly impressive is the fact that Spain now has the most cost-efficient banking sector. While still below the eurozone’s capital adequacy rate, the Spanish banking sector has been improving its capital ratios. France looks relatively stable with solvency on the rise. However, a key challenge remains in terms of generating margin expansion. The Netherlands stands out for the improvements to its banking system’s cost-income ratio –the result of a considerable digitalisation effort– and the growth in its RoE. Concern is concentrated in Italy, where margins and returns have yet to reflect the potential medium-term impact of the country’s non-performing loans. Specifically, NPL ratios for loans made to firms are over 20% while NPLs for household debt stand at close to 10%.

In conclusion, financial stability in the eurozone appears to be headed in the right direction, moving away from the fears and circumstances that unleashed the sovereign debt crisis in 2012. Nevertheless, the looming shift in monetary policy conditions represents a challenge to a financial sector that has been propped up by a series extraordinary liquidity measures over the past 6 years. In terms of bank solvency, Italy remains the primary focus of concern. This autumn’s stress tests performed by the EBA and ECB will provide the next important measurement for assessing these concerns.

Notes

References

CARBÓ S., and F. RODRÍGUEZ (2018), El futuro de la rentabilidad bancaria: ¿tecnología o una nueva demanda? [The future for bank profitability: Technology or new demand?] Papeles de Economía Española, 155: 62-73.

Santiago Carbó. CUNEF and the Funcas Observatory of Financial Digitalisation

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. Granada University and the Funcas Observatory of Financial Digitalisation