Challenges for Spanish banks: 50 years after deregulation

Since its deregulation 50 years ago, the Spanish banking sector has been shaped by significant structural transformation as a result of the need to adapt to an ever-changing environment, to which it has demonstrated resilience and flexibility. On top of profitability pressures, the management of risks under the growing regulatory push to increase solvency, on the one hand, and technological challenges, on the other, remain the most important issues facing the Spanish banks in the years to come.

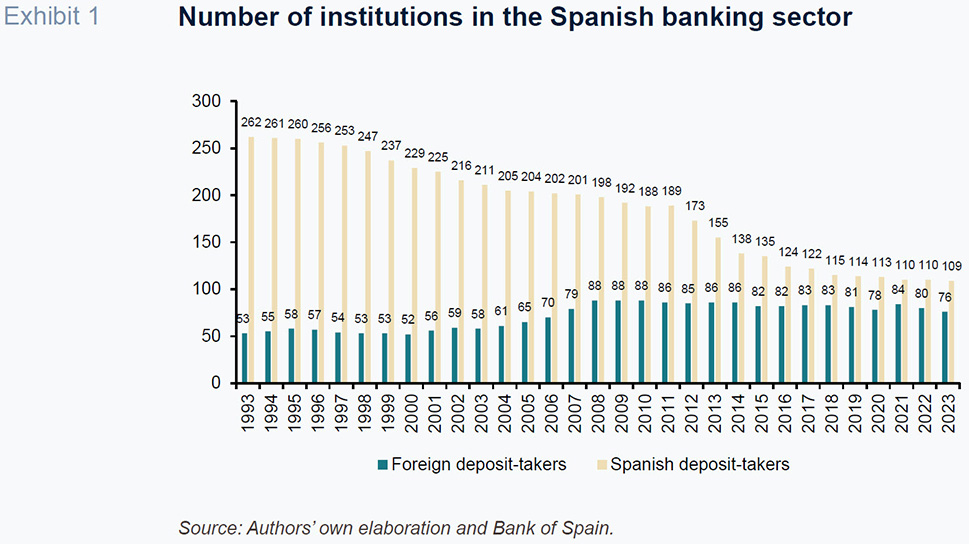

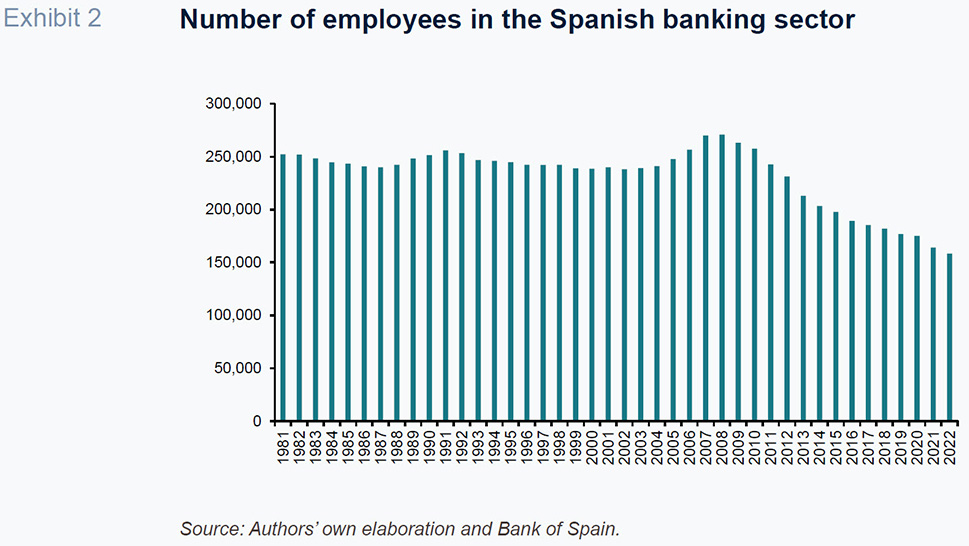

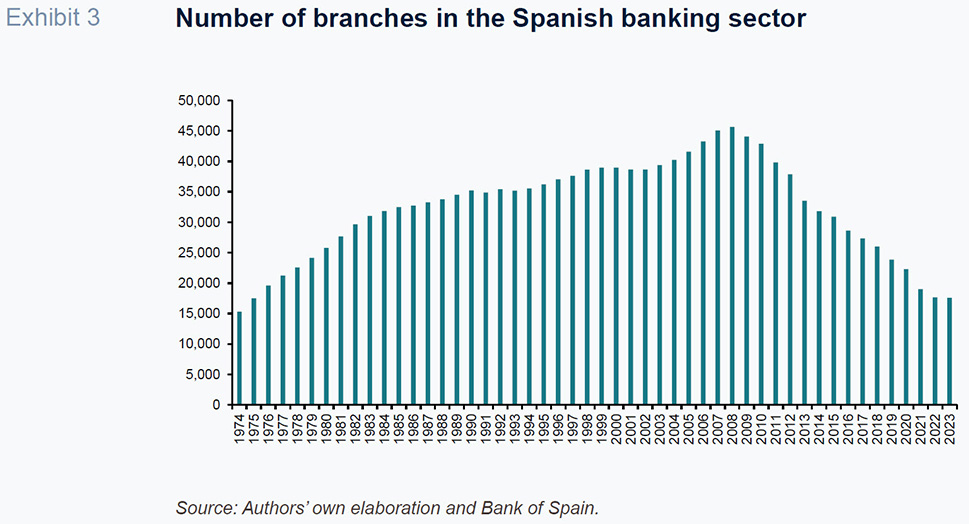

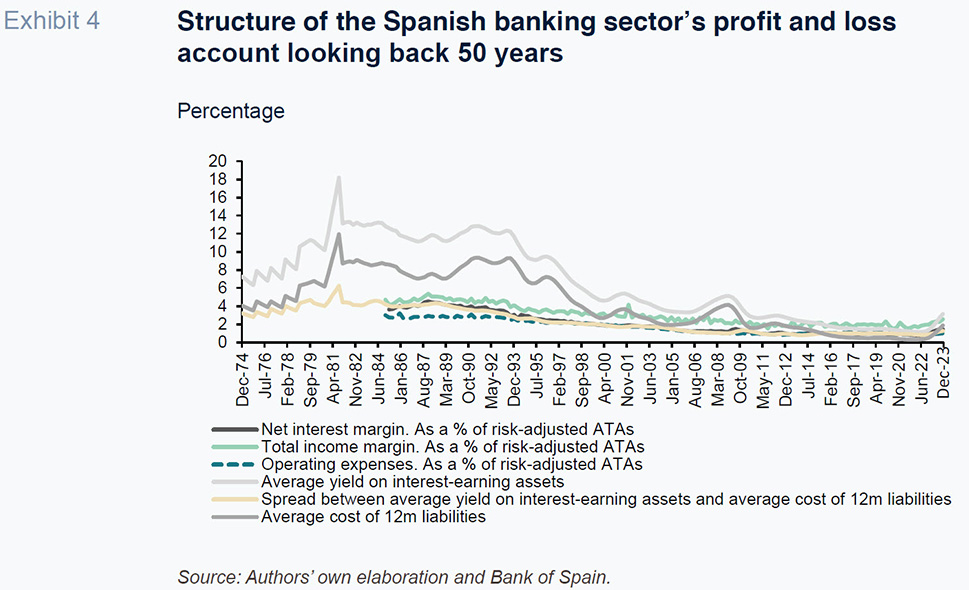

Abstract: The Spanish banking sector, since its deregulation 50 years ago until today, has been shaped by significant structural transformation as a result of the need to adapt to a changing environment and respond to challenges. Indeed, Spanish banks have demonstrated resilience and the ability to adapt to changes in market conditions, financial regulation, disruptive technology and global economic crises. Firstly, it is essential to acknowledge that the sector deregulation embarked on in the 1970s unleashed a series of changes that have profoundly redefined the Spanish banking landscape. The number of deposit-takers in Spain has decreased significantly, from 262 in 1993 to 109 in 2023, illustrating the scale of sector consolidation in response to economic challenges and opportunities to increase efficiency. There has also been a contraction in sector employment, from 270,085 jobs in 2008 to 158,217 in 2022, and in the number of bank branches, from 45,662 in 2008 to 17,603 in 2023. These figures underscore the banks’ shift to a more technology-heavy model less dependent on physical infrastructure, evidencing a transition towards digitalisation and operational efficiency in response to new market demands and competitive pressures in a globalised financial environment. In tandem with these structural changes, the composition of the banks’ income and expenses has evolved significantly, encompassing efforts to navigate the ultra-low rate environment in the wake of the financial crisis as well as remarkable efforts to boost cost-to-income efficiency. On top of profitability pressures, the management of risks under the growing regulatory push to increase solvency, on the one hand, and technological challenges, on the other, remain the most important issues facing the Spanish banks in the years to come. On this last point, the banks will need to balance the search for scale against the agility required to adapt to new technology and shifting customer expectations.

A sector forged by new market demands

Fifty years ago, the Spanish financial sector embarked on a path towards deregulation with the Banking Sector Act of 1974, which ushered in a period of intense changes that began in 1977 and accelerated when Spain entered the single European market. In the following decades, the financial sector has experienced major changes and challenges, punctuated by international financial crises, steady reinforcement of solvency requirements (and of international coordination to bring them about) and increasingly abundant regulations, particularly from 2008. Along the way, the Spanish banking sector has emerged with a strong international footprint and a high level of resilience, although the number of players and the strategic role of technology have changed significantly over the years.

This paper looks back at the major changes in the structure and profitability of the Spanish banks. Due to space constraints, it only provide a cursory approximation of a journey that has been tremendously complex and intense. We also attempt to provide a snapshot of the state of play in the Spanish banking sector today and its medium- and long-term prospects.

Indeed, certain recent developments highlight the complexity of the current financial environment. The markets expect the main central banks to start to lower their official rates soon, having increased them sharply in recent years in order to tame inflation. Contrary to initial expectations, it now looks as if the European Central Bank (ECB) could move ahead of the Federal Reserve in announcing the first rate cut, although its messaging remains cautious and its approach, highly contingent.

In parallel, the Spanish market has recently been shaken up by BBVA’s attempt to acquire Banco Sabadell. Irrespective of the final outcome, this takeover attempt is driven by the need to reinforce aspects which the financial environment sees as essential for any financial institution. Those aspects include gaining critical mass so as to be able to access the liquidity markets from a position of strength and the need to consolidate large and geographically diversified customer bases to create a service strategy that is increasingly articulated around supply through large digital business platforms.

Elsewhere, over the past few weeks, the banks reported their results for the first quarter of 2024, with the top six Spanish banks reporting aggregate profits of 6.57 billion, year-on-year growth of 15.3%. Recall that since the financial crisis of 2008, the Spanish and European banks had been finding it very hard to eke out returns due to a mix of regulatory pressure, the need to evolve their business models and ultra-low or even negative official interest rates. Now that rates are higher, a cornerstone of the public debate has turned to considering what level of profitability reflects sufficient competition, while new and equally important factors and risks are emerging, albeit more silently. The latter include: i) the need for the deposit-takers to move with caution, as they continue to face difficulties in generating credit; ii) the macroeconomic climate, which remains subject to geostrategic swings; and, iii) technology, which is dictating significant changes in the business environment.

50 years of transformation

Five decades on from the start of banking deregulation in Spain, the sector has undergone a similar transformation to that observed in other large international economies, albeit preserving certain unique traits. For example, some of the Spanish banks have pursued major international expansion, which, over time, has consistently proven a successful diversification and organic growth strategy. Spain has also remained a country whose banking sector commands a relatively greater presence in the economy’s financing flows, as well as one with a denser branch network, although technological change and a wave of concentration have prompted a shift in the customer service model that has triggered certain adjustments. Spain has also been one of the countries where bank crises have brought about more intense concentration processes, albeit not necessarily to the detriment of competitive intensity. It is also worth recalling that for many years the Spanish banking industry was institutionally diversified and although it has since undergone a degree of standardisation in order to access the market and reduce scrutiny following successive financial crises, it retains its wealth of diverse business cultures and regional heritage. Lastly, the Spanish banking sector has consistently proven a pioneer in adopting new technology and, as with other international sectors, now faces what is possibly its biggest challenge in many years in this respect.

From a structural perspective, a good approximation is the trend in the number of financial institutions. The data, obtained from the Bank of Spain, reveal a particularly intense contraction in the 1990s. In the previous two decades, the sector had already been concentrating but after a major credit crisis, that process began to accelerate. Following the financial crisis of 2008, the number of deposit-takers decreased intensely. As shown in Exhibit 1, between 1993 and 2023, the number of Spanish banks went from 262 to 109, a reduction of 58.4%. Over that same 30-year period, the number of foreign banks with branches in Spain increased, from 53 to 76.

Elsewhere, as shown in Exhibit 2, sector employment has also decreased considerably. After 30 years with a workforce steady at around a quarter of a million, the 2008 financial crisis triggered a reduction from 270,085 employees that year to 158,217 in 2022, the last figure available.

As for the branch network, deregulation emerged as an element of regional competition, so that branch numbers actually increased very considerably. The number of branches went from 15,311 in 1974 to 45,662 by 2008. Since then, however, the post-crisis rationalisation and digitalisation processes have reduced their number to 17,603 branches by 2023.

Using these figures, the ratio of employees per bank has barely changed, going from 9.1 in 1981 (the first year with comparable data) to 9 in 2022, despite the fact that the branch structure and customer service model have undergone significant transformation, marked by the automation or online processing of many banking transactions (direct debits, cash withdrawals, transfers, etc.) to focus more on business-generating leads and credit/investment portfolio management. This means that much of the sector’s productivity gains has been brought about by technological change (fewer branches, more automation and digital services).

In tandem with these structural changes, the composition of the banks’ income and expenses has evolved significantly, as shown in Exhibit 4, which depicts the trend in some of the main headings of their profit and loss accounts. The effects of sector deregulation, European convergence and competition are clear in the trend in margins. The sector’s net interest margin (as a percentage of average total assets), for which there are quarterly figures going back to 1985, decreased from 3.63% that year to 1.44% in 2023. In the years following the financial crisis, that margin fell even further, to around one percentage point, against the backdrop of ultra-low interest rates. The banks were able to mitigate some of the pressure on their net interest margins following the financial crisis with fee and commission income, so that their total income margin (a measure which includes net fee income) has held steady at around 2% since then. The effort to boost cost-to-income efficiency is also remarkable, with operating expenses decreasing from 3% of average assets to 1% between 1985 and 2023. The trend in profitability is possibly the most eye-catching takeaway from the exhibit. The yield on interest-earning assets went from double-digit figures for much of the 1980s and 1990s, then embarking on a steady downtrend to a low of 1.15% in June 2022, as a result of a protracted period of ultra-low or negative interest rates. In 2023, after rates went up, allowing market conditions to normalise somewhat, that yield recovered to 3.15%.

Prevailing risks and challenges

Capturing the full spectrum of complexities and strategic challenges that have accumulated for the banks in recent years is hard to sum up in a few lines. [1] On top of the pressure on profitability, the management of risks under growing regulatory pressure to increase solvency, on the one hand, and technological challenges, on the other, remain the most important issues facing the Spanish banks in the years to come.

With respect to their solvency and risk management challenges, the analysis recently published by the Bank of Spain in its April 2024 Financial Stability Report is particularly detailed and useful. That report highlights how the banks’ common equity tier 1 capital (CET1) ratio increased a slight 17 basis points from year-end 2022 to 13.2% at the end of 2023. In 2023, the CET1 ratio gap between the Spanish banking system and other important European banking systems widened, despite widespread improvement in the Spanish banks’ return on equity. At year-end, the Spanish CET1 ratio remained below the levels reported by Germany, France, Italy and the Netherlands. As suggested by the Bank of Spain, although Spain’s lower capital level may be partly attributable to structural factors, such as lower use of internal models and greater asset density, it should be noted that, despite the increase last year, the increase in the Spanish system’s CET1 ratio was the lowest among the comparable benchmark economies.

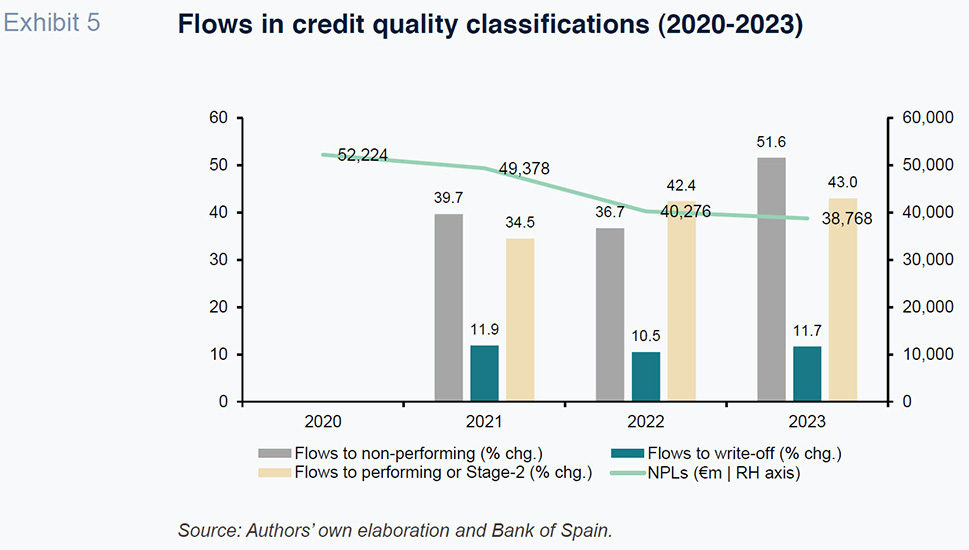

Importantly on the risk management front, the Spanish financial institutions have been managing their non-performance proactively, so that despite the panorama painted by the pandemic (foreshadowing a significant uptick in non-performance), the system’s NPL ratio has been steady at around 3.5% since 2022. Exhibit 5, based on information from the Bank of Spain’s

Financial Stability Report, shows, in fact, that non-performing exposures have actually decreased from 52.22 billion euros in 2020 to 38.77 billion euros in 2023. The main contributing factor has been the fact that the flow of non-performing loans to write-offs (average annual rate of between 10% and 12% during that same timeframe) and newly non-performing loans has been largely offset by the flow of non-performing loans to performing (recoveries) or Stage-2 exposures.

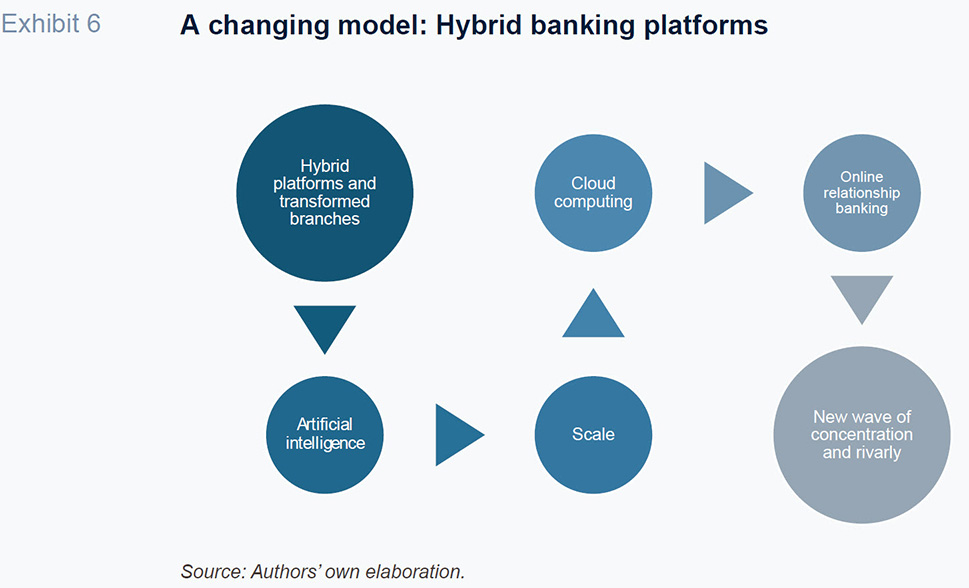

In sum, the banking sector remains caught in the plight of having to balance the need to generate sufficient returns to keep shareholders happy and convince the markets with regulatory pressure to maintain and even shore up their solvency levels. The other major challenge it faces is the need to adapt the business model to a technology-heavy model articulated around a banking-as-a-service platform. As depicted by Exhibit 6, this change is necessarily hybrid in two ways. Firstly, these platforms can be configured in multiple ways, so as to offer proprietary services only or to provide them together with other technology or financial service providers. Secondly, the banks’ branches continue to provide value, even though their configuration has changed and their role is diminishing. In parallel, the banks are having to upgrade their skills, often with outside help, in fields where they have started from somewhat of a disadvantage with respect to other non-financial companies, such as artificial intelligence and cloud computing. Ultimately, the aim is to build sufficient scale to make money from the platform and retain a competitive edge. All of which without losing their value as a relationship business in which the customer comes to identify with his or her bank, something that used to materialise at the bank branch but now, increasingly, has to happen over the platform. Lastly, as shown in the exhibit, the competitive landscape is being marked by growing concentration (to achieve that scale), which should not necessarily impede competition, as the platform model knocks down the distance barrier in bank services, opening up the market to new players.

Looking back and looking forward

The Spanish banking sector, since its deregulation 50 years ago until today, has been shaped by significant structural transformation as a result of the need to adapt to a changing environment and respond to challenges old and new. This journey, in spite of its challenges, has demonstrated the sector’s resilience and ability to adapt to changes in market conditions, financial regulation, disruptive technology and global economic crises.

Firstly, it is essential to acknowledge that the sector deregulation embarked on in the 1970s unleashed a series of changes that have profoundly redefined the Spanish banking landscape. Deregulation ushered in more intense competition and triggered significant expansion, in Spain and abroad. The Spanish banks not only increased their global presence but also proved adept at embracing new technology and business models to enhance their efficiency and customer service.

Secondly, the banking sector has proven its ability to manage risk and increase its solvency. Although it has been increasing its common equity tier 1 (CET1) ratio steadily, that ratio remains lower than that of other European economies, making this an ongoing quest.

The challenges along the way have not been minor. Digitalisation has been one of the most significant and constant challenges. Digital transformation has not only changed how the banks operate internally but also how they relate with their customers. The transition from a service model based on physical branches to one articulated around digital platforms (with a certain amount of co-existence between the two models) has required significant investments in technology, as well as a cultural shift inside the organisations.

Lastly, the leap in scale has allowed the Spanish banks to build the capability to handle larger transaction volumes and offer a broader suite of financial services, from retail banking to corporate and investment solutions. This is particularly relevant in a context in which digitalisation and demand for personalised and online-friendly banking services continues to grow. Effectively achieving the required critical mass is not without its challenges, however, especially in an environment in which market dynamics are changing rapidly and competitive pressure from fintechs and other newcomers is proving intense. The banks need to balance the need for scale against the agility required to adapt to new technology and shifting customer expectations.

Notes

Santiago Carbó Valverde. University of Valencia and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas