Strong recovery in 2021 tax revenue: Contrasting with the previous crisis

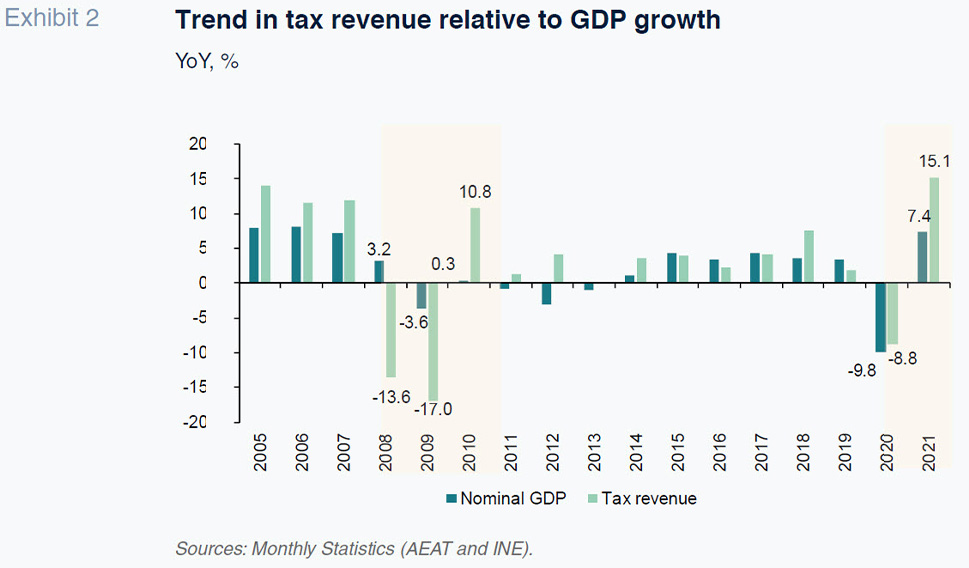

The contraction in 2020 tax receipts as a result of the pandemic and the associated mobility and business restrictions was mitigated by the government´s crisis response measures. In contrast to the wake of the previous crisis of 2008, in the space of just one year, 2021 tax revenue increased 15.1%, topping pre-pandemic levels- a trend that, under current assumptions, is expected to continue into 2022, albeit at a slower pace.

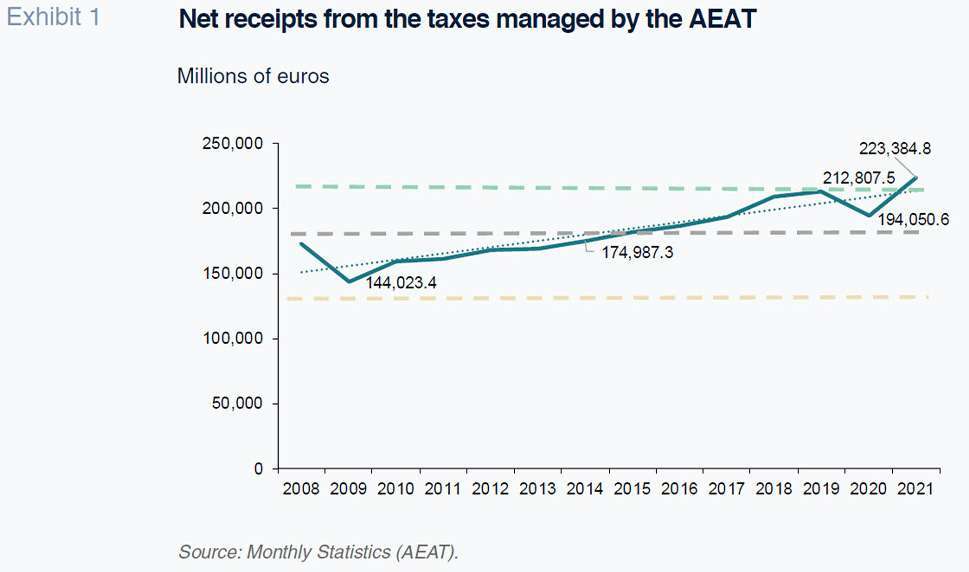

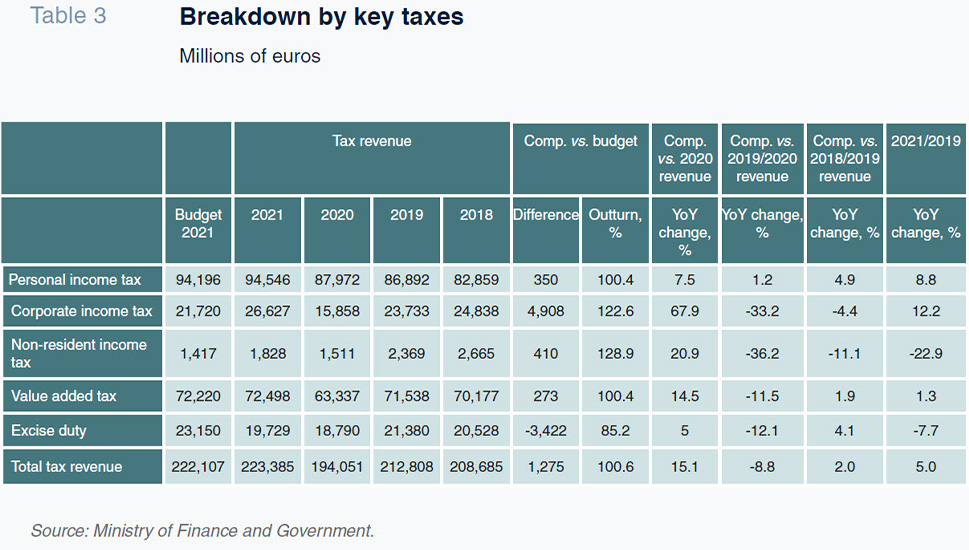

Abstract: The revenue managed by Spain’s tax authority, the AEAT, over the past decade has registered average annual growth of 2%. Tax revenue peaked in 2021 at 223.39 billion euros, rebounding by 15.1% from 2020, when receipts contracted. This contrasts with the slower and more gradual recovery etched out from 2010 onwards in the wake of the 2008 crisis. The two most noteworthy aspects of the trend in tax revenue in 2021 include the fact that: (i) the correction lasted for just one year; and (ii) it was followed by a strong recovery to above pre-pandemic levels in the span of just one year. The differential performance of the recovery in tax revenues during the two crises can be largely attributed to the different institutional measures implemented to mitigate their consequences and the healthy pace of recovery in the tax bases of each of the main taxes, both those related with income and, especially, those associated with consumption. That last factor bodes well for continued healthy tax collection dynamics in 2022, shaped by economic growth, albeit with more moderate growth than initially anticipated on account of the war in Europe and, above all, ongoing high inflation. These favourable tax dynamics, however, rest on the assumption that the measures passed to tackle the crisis unleashed by the war thus far, including the associated tax breaks, do not remain in place for an extended period.

Positive tax collection trend over the past decade

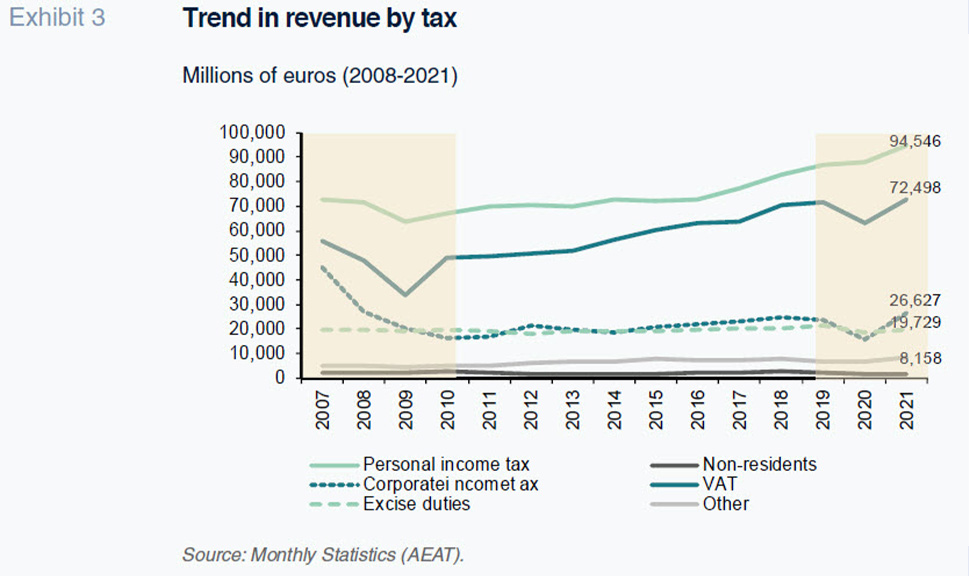

Revenue from the taxes managed by the Spanish tax authority, the AEAT, has been trending higher since the financial crisis, registering average annual growth of 2% since 2009. Although the snapshot for the public coffers during that time is positive, it is important to recall that Spain has had to navigate two crises during the last 13 years. However, the reasons underpinning each were radically different, as were the government’s responses and measures to tackle their economic and social ramifications. As a result, the impact on tax revenue has also been different in terms of intensity and the specific impact on the different taxes.

The crisis unleashed in 2008 was characterised by a slower recovery in tax revenue, as it took five years for revenue to revisit pre-crisis levels, with receipts plummeting in 2009 (-17% YoY), by far more than the contraction in GDP (-3.6% YoY). In contrast, in response to the more recent crisis of 2020, the government passed a specific package of measures designed to mitigate the fallout from the coronavirus, sized at nearly 80 billion euros between 2020 and 2021. That response: i) contained the drop in revenue in 2020 to 8.8% year-on-year, which is one percentage point less than the contraction in GDP; ii) limited the duration of the crisis to just one year – the economy rebounded in 2021, fuelling significant growth in revenue (+15.1%, above the growth in nominal GDP of 7.4%); and iii) unlocked tax receipts in 2021 that topped pre-pandemic levels by over 10 billion euros, to reach a record level of 223.39 billion euros, which was 1.3 billion euros above the figure budgeted for 2021.

Impact on tax revenue of the health and economic crisis of 2020 by comparison with the financial crisis of 2008

As already noted, the most remarkable thing about the impact on tax revenue of the crisis of 2020 is the speed of the recovery to pre-pandemic levels, most notably towards the end of 2021, thanks to the recovery in employment and jump in inflation.

The pace of recovery of pre-crises tax revenue levels was radically different in both crises. Tax revenue increased by 15.1% in 2021, well above the recovery observed in the wake of the previous crisis – five points above the growth registered in 2010 and even more so compared to the rates of growth sustained in subsequent years (2011-2019).

However, in contrast to what happened in 2021, the healthy pace of recovery in revenue observed in 2010 was not enough to push receipts back above the previous highs of 2005. It took until 2018, a year of significant growth in tax revenue (+7.6%), for Spain to revisit 2005 levels, with growth over most of the previous years limited to less than 5% year-on-year.

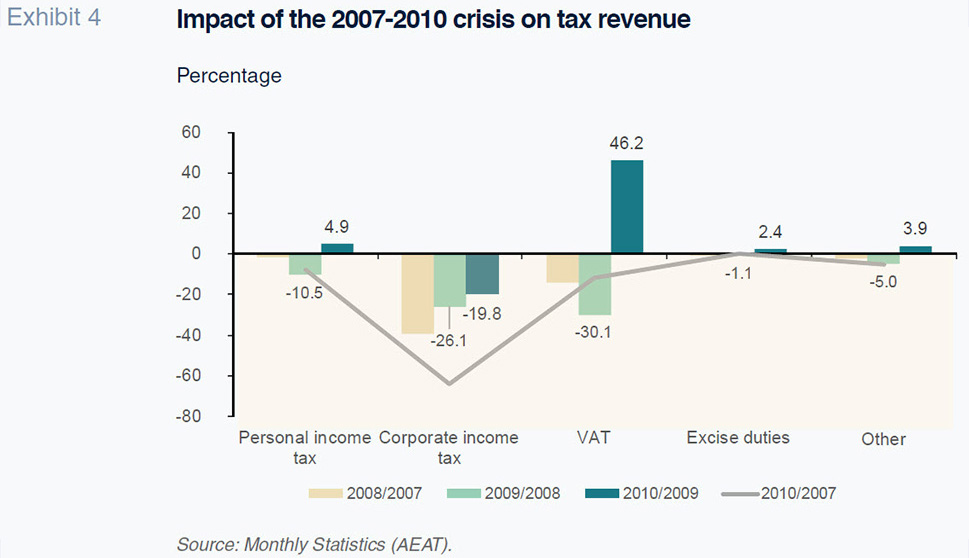

The factors driving the recovery in tax revenue also differed starkly between the two crises. The growth in revenue in 2010 was mainly attributable to the reduction of the refunds in personal income tax (PIT), corporate income tax (CIT) and VAT that were applied for in respect of 2009 (reimbursed in 2010), with a cash impact in 2010 of 11.35 billion euros.

[2] There was also an increase in revenue from payments deferred in prior years and the results of inspections, which increased by 25.2% from 2009 (2.45 billion euros).

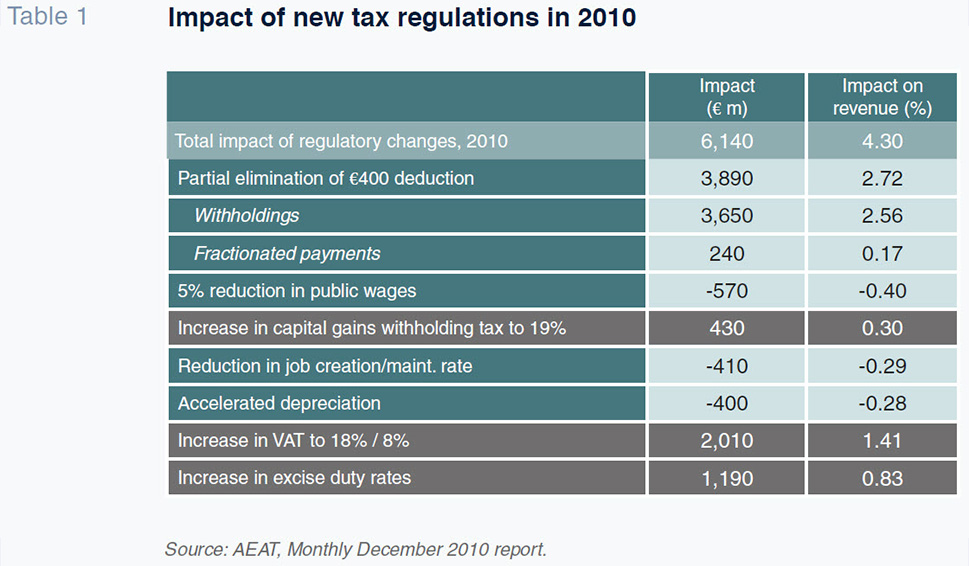

However, the trend in tax revenue in 2010 was shaped above all by the boost provided by the fiscal austerity measures passed. Those measures had an estimated impact of 6.14 billion euros, which was responsible for revenue growth of 4.3 points. Stripping out that impact, the adjusted rate of growth in tax revenue would have fallen to 6.5%. The main tax regulation changes included partial elimination of the 400-euro tax deduction in withholdings and fractionated payments, with an impact of almost 3.9 billion euros; the increase in indirect tax rates, including VAT (impact of +2 billion euros) and excise duty (+1.19 billion euros).

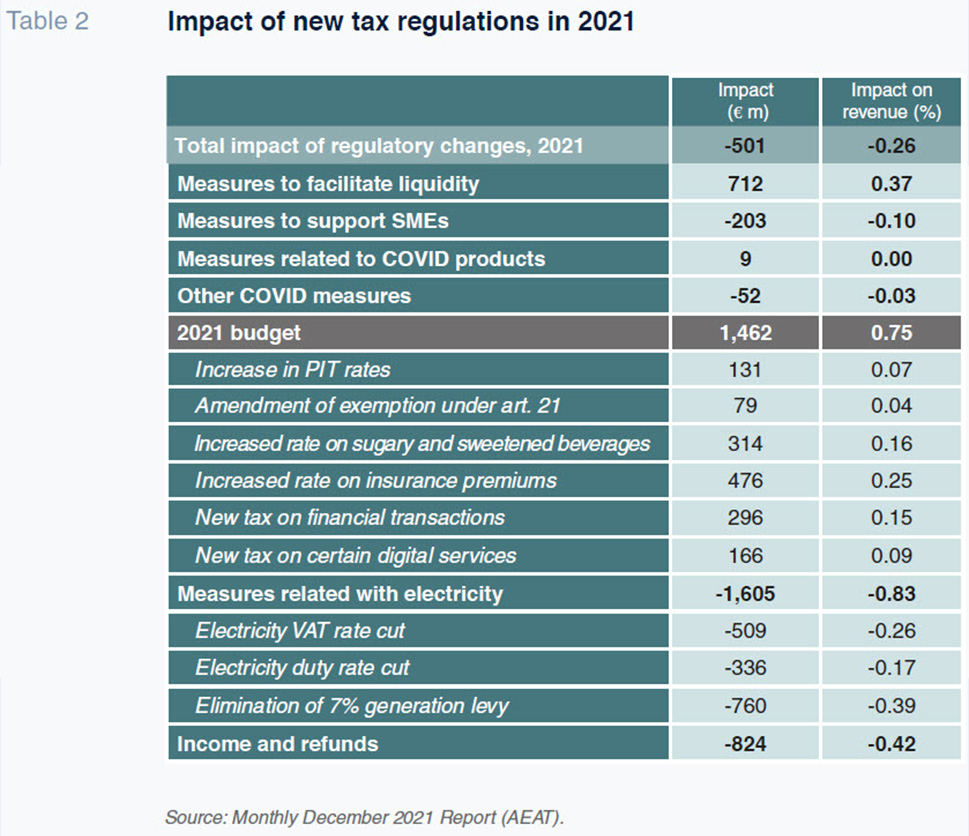

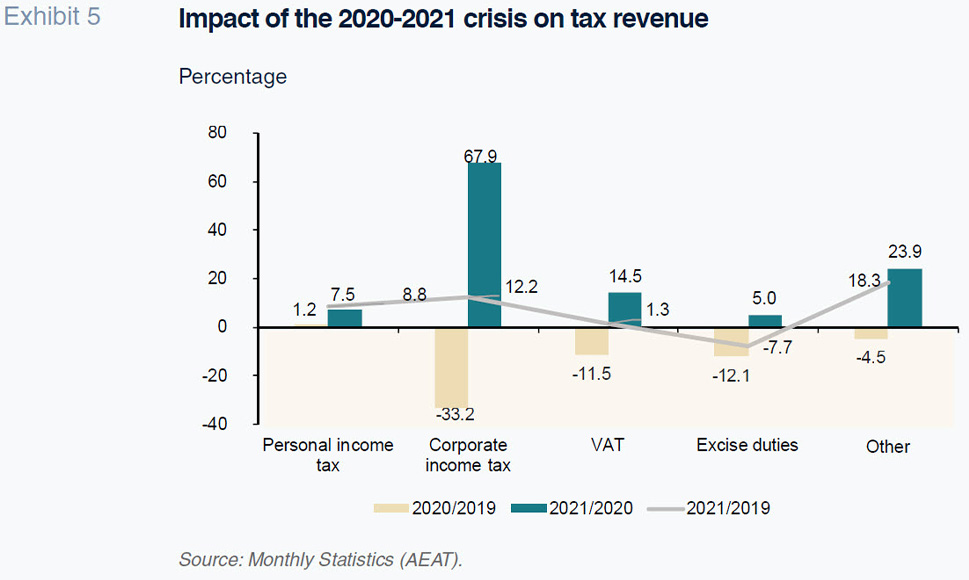

In contrast, returning to 2021, the main reason for the growth in revenue was the recovery in the various tax bases, which increased by 12.7%, topping 2019 levels by 4%. On the other hand, unlike in 2020, the numerous and varied regulatory measures and changes rolled out in 2021 had a limited impact on tax revenue in net terms. Isolating the effect of the measures approved in conjunction with the 2021 state budget, a year of higher taxation wherewithal, the net impact is estimated at just 0.75% of the effective growth.

The differences are even more pronounced when we dig down into the trend in each of the main taxes in the most critical years, particularly in the case of PIT. During the previous crisis, the drop in PIT revenue in 2009 coincided with a drop in gross household income of around 2.5%, compared with growth of 4% in 2008. All components of pre-tax income deteriorated, but earned income contracted the hardest (-0.4% vs. +7.1% in 2008) affected by the loss of paid employment (-6.2%) and slower growth in average wages. In contrast, public wage, pension and jobless claim dynamics remained positive (+8.5%), confirming their role as automatic stabilisers in times of crisis. Other components that corrected sharply were capital income (-8.6%) and income from business activities (-11.8%). In contrast, in 2020, PIT was the only tax to register slight revenue growth (+1.2%). The reason for that growth in such an adverse climate as that of the pandemic was the offsetting role played by public wages and pensions –as was the case in 2009– which registered growth all year long, in tandem with the income support measures, such as the furlough scheme, curtailing the immediate impact on tax revenue. Note additionally with respect to the comparison with 2019, the bulk of the refunds associated with maternity benefits took place that year. [3] The 2020 result was also positively affected by a good performance in other items, including annual taxpayer returns and, less significantly, withholdings against investment funds. In the other items of income (employee withholdings in the private sector, fractionated payments by businesses, withholdings against securities capital gains and leases), the decline was the result of the general economic situation.

Corporate income tax patterns were also different, not in terms of the contraction (sharper in 2020) but rather, the recovery. After the financial crisis, it took until 2012 for corporate income tax to take off meaningfully, albeit remaining well below the peak recorded in 2007 (44.8 billion euros). Indeed, that record has not been matched again, the second highest benchmark being 2018, when CIT revenue was 55% of that peak. However, following the sharp correction of 2020 attributable to the drop in fractionated payments, to 66% of 2019 levels, the recovery in 2021 was explosive, to over 26.6 billion euros, the highest level since 2008 (and nearly 60% of the 2007 record). It is worth highlighting the fact that that performance was impressive not only by comparison with such an adverse year as 2020, but also compared to 2019, improving 12% on that reading. That performance was driven by two circumstantial factors, which could foreshadow more moderate growth in the years to come: (i) non-recurring transactions in 2021 (stripping them out, the growth in revenue compared to 2019 narrows to 3.1%; and (ii) the relevance of the refunds applied for in 2018, with an impact in 2020, a pattern not repeated in 2019, such that the volume of refunds in 2021 decreased significantly year-on-year.

The differences in the correction and recovery patterns in VAT and excise duties are less pronounced. However, the contraction in VAT revenue in 2009 was far more aggressive than in 2020 (30.1% vs. 11.5%), shaped by the prior-year levels and the different causes of the crisis, with a particular impact on indirect taxation (bursting of the retail bubble). As already noted, in both instances, the recovery got off to a swift start and was complete within one year from the initial contraction, but the underlying drivers were different – rate hikes in 2010 vs. recovery in tax bases in 2021. The recovery in 2021 would have been even stronger were it not for the cut in the rate on electricity consumption applied at the end of June, which meant foregoing 500 million euros of revenue.

Note, lastly, that the buoyancy in “Other taxes” in the recent crisis is associated with new taxes introduced and the increase in the rate of tax levied on insurance premiums, with an impact of over 476 million euros. The new taxes (financial transactions and certain digital services), despite not reaching the initially forecast levels, brought in around 462 million euros in 2021.

Momentum in revenue during the second half of 2021, solidity of the revenue recovery and outlook for 2022

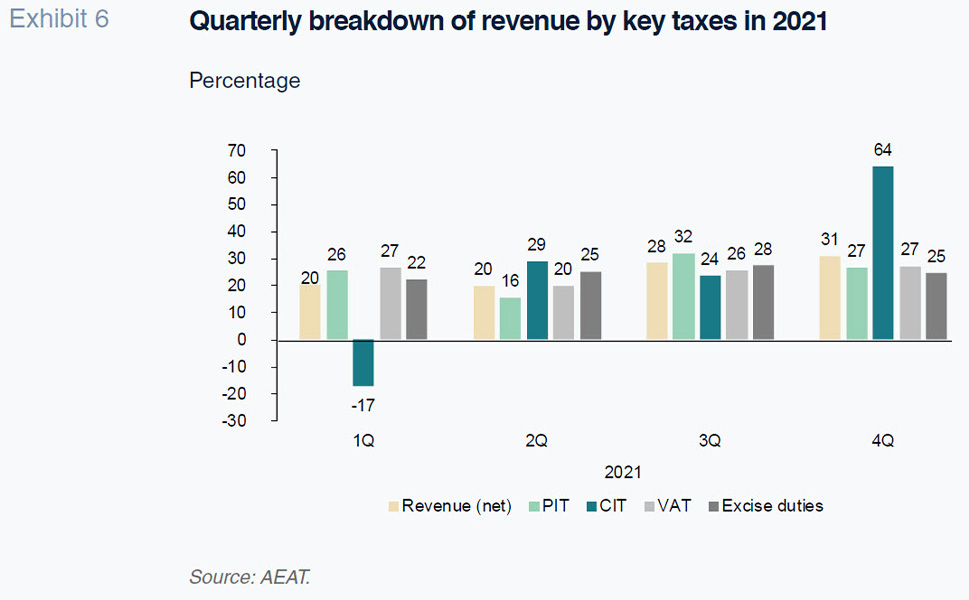

The unique circumstances unfolding in 2021 drove tax revenue in Spain to record levels. Analysing the dynamics by quarter shows how momentum really increased during the second half of the year. The impact of the measures rolled out to contain the collateral effects of the pandemic in the form of income support measures, coupled with the arrival of the vaccine at the start of the year and its rapid rollout, unlocked a recovery in economic activity and clearcut improvement in the job market. Social security contributor numbers began to register growth from 2019 levels from June and reached 2% by December, albeit still shaped by prolongation of the furlough scheme. In parallel with that recovery in economic activity, global supply chains became disrupted, [4] triggering a spike in prices, a phenomenon that accelerated sharply towards the end of the year when inflation averaged close to 6%.

That economic context impacted the recovery in revenue throughout the year, paving the way for the boom in the fourth quarter, when revenue amounted to 69.47 billion euros, one-third of the annual total and three percentage points above pre-pandemic averages. [5]

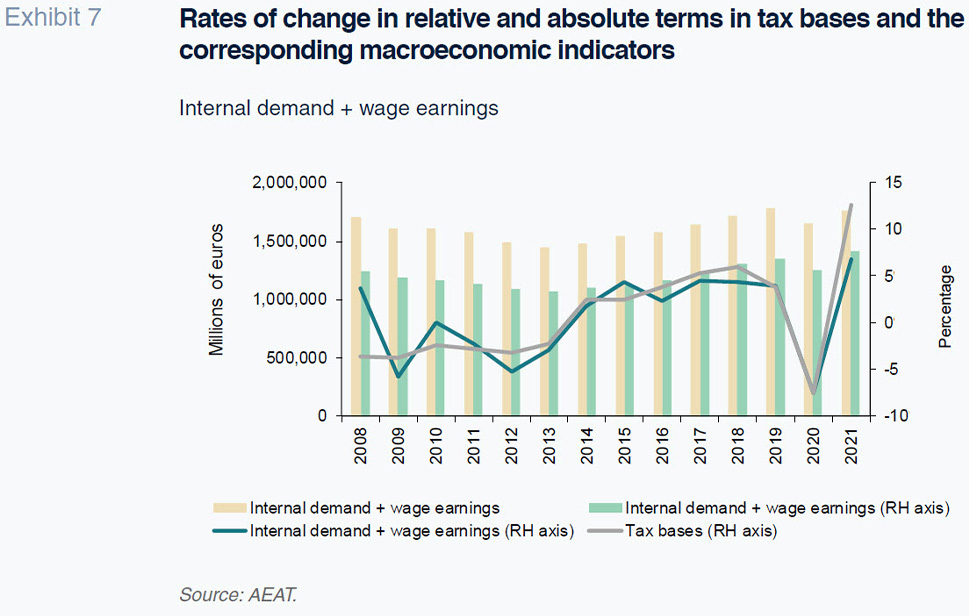

As noted at the start of this paper, one sign of the solidity of the recovery in tax revenue in 2021 is the positive trend in the tax bases for the main taxes, which increased 12.7%, outpacing the contraction observed in 2020 (-7.5%), leaving them 4.2% above 2019 levels. The growth in tax bases topped the growth in internal demand and employee compensation (-2.5%), the macroeconomic indicator typically used as the benchmark for the former. The explanation for that disparity lies with that fact that some bases, including corporate earnings and the value of energy product consumption, which take time to trickle down to the macroeconomic indicator, drove growth in the tax bases. [6]

The trend in tax bases throughout 2021 was also marked by the comparison with 2020 and the various events taking place that year, namely the lockdown and business and mobility restrictions. The start of the year was marked by moderate growth due to the spike in the caseload at the end of 2020 and start of 2021, as well as the one-off effect of the winter storm, taking off from the second quarter, due to the contrast with the sharp contraction sustained during the harshest months of lockdown. Throughout that second half, that growth continued however, remaining above 13%.

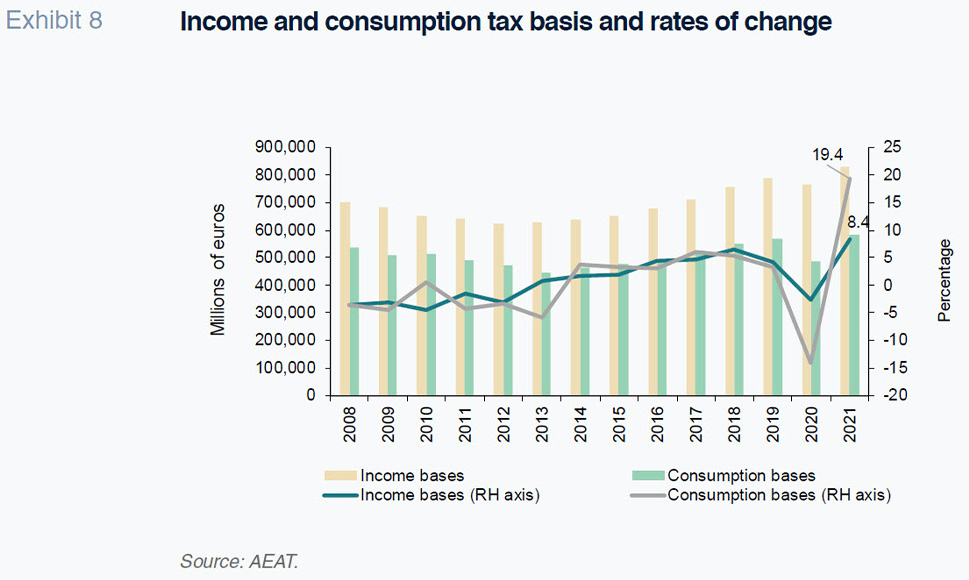

Distinguishing between income and consumption bases, we note that the latter registered more intense growth (19.4% YoY) than the former (8.4%) due to the relatively greater deterioration of consumption in 2020, whereas income was less affected thanks to public income sources (public sector wages, pensions, furlough scheme, income support for the self-employed). Consumption really took off in the second half (spending remained below 2019 levels during the first half), boosted by inflation towards the end of the year.

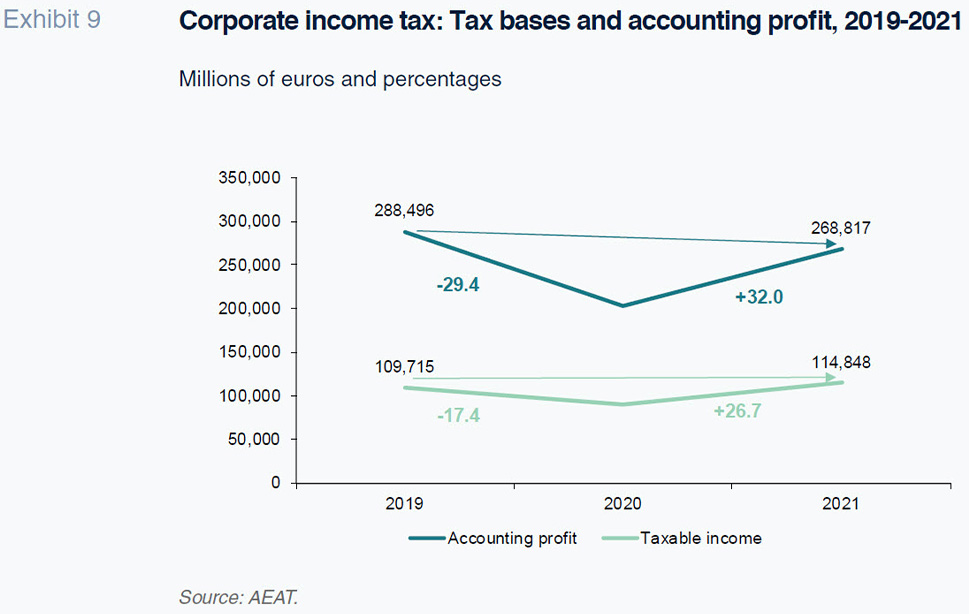

It is worth taking a closer look at the trend in the corporate income tax base, which registered such strong growth in 2021, in order to assess the feasibility of that level being repeated and the prospects for growth. In 2021 the CIT tax base registered growth of 26.7% from 2020 and of 4.7% from 2019. Corporate earnings, meanwhile, registered growth of 32%, due to the contraction sustained in 2020 but also, as already noted, the impact of one-off transactions (a bank merger and major asset sale by a corporate). By comparison, earnings remained 6.8% below 2019 levels. The fractionated payment statistics indicate that the growth in profits and tax base was higher at groups –even stripping out the one-off transactions– relative to the large companies and SMEs that file their taxes on the basis of their earnings for the year.

The contrast between the growth in revenue –of over 64%– in 2021 relative to that in taxable income (+26.7%) suggests that 2022 is likely to mark an inflection point with respect to 2021, which was largely attributable to circumstantial factors.

Looking at the health of the year-end 2021 dynamics, in 2022 it is likely, assuming that the tax system will not be reformed in line with the recommendations made by the committee of experts set up to that end, that tax revenue will register further growth, of around 4.3%, which is lower than expected when the budget was drawn up, due to the armed conflict in Europe and the likely protraction of supply chain bottlenecks. In 2022, the measures rolled out by the government in response to the war in Ukraine will reduce tax revenue –for at least one quarter– as a result of the electricity tax cuts passed.

[7] The main risk lies with the potential need to leave those measures in place for longer than initially expected, considering that the ministry estimates an overall impact over a 12-month period of 10 to 12 billion euros.

It is foreseeable that the impact of lower growth will be offset by the protraction of inflation at high levels, such that we are forecasting growth in nominal GDP of 8.5% in 2022. Framed by those expectations, and in the absence of fresh shocks, tax revenue momentum should gather, underpinned by a recovery in aggregate tax bases above pre-pandemic levels.

Notes

Whereas in 2008 the economic and financial crisis was triggered by the bursting of the real estate bubble, the crisis of 2020 was attributable to the health emergency induced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

AEAT, monthly December 2010 report.

Following a sentence ruling that maternity benefits were tax exempt.

Triggered by the recovery in activity and the difficulties some countries faced in responding to demand due to an explosion in COVID cases.

In 2018 and 2019, fourth-quarter revenue amounted to 30% of the annual total, compared to 33.2% in 4Q21. In year-on-year terms, growth accelerated in the fourth quarter to 17.5%, compared to 11% in the third quarter.

Those disparities, as noted by the AEAT itself, are also evident in the bases that are more closely correlated to indicators, such as wages: the stock of wages gleaned from 2021 tax returns was 3.1% above 2019 levels, while the pool of wages and salaries estimated in the national accounts was 0.8% below that threshold.

VAT cut to 10%, electricity excise duty cut to 0.5% and temporary suspension of the 7% levy on the value of electricity generated.

Susana Borraz Perales and Montaña González Broncano. Afi – Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.