State guarantees and latent non-performance

Spain´s public guarantee scheme has served to ease the effects of the pandemic and now of the war on the country´s business segment, thus containing the materialisation of non-performing loans. Going forward, while a potential increase in the incidence of business non-performance is expected in the near-term, the increase in NPL coverage should be mitigated by the strong provisioning efforts of the banks, together with their limited exposure thanks to the state guarantee scheme.

Abstract: One of the most noteworthy measures taken by the government to mitigate the effects of the war in Ukraine is the approval of a new state guarantee programme and extension of the maturities of the loans awarded under the pandemic guarantee scheme in an attempt to prevent geopolitical tensions from having compounding adverse effects on top of the toll taken by the pandemic. Extension of outstanding state guaranteed loans will come as a lifeline for the sectors and businesses most affected by the two crises. In the case of the banks, it will contain the materialisation of associated non-performance. Nonetheless, the increase in riskier stages of public guarantee scheme (PGS) exposures could translate into growth in non-performance in the business loan segment, with the potential impact substantially higher in Spain than in Europe due to the higher weight of PGS exposures in total outstanding business loans. The possible increase in non-performance is highly sensitive to both the level of impairment of stage-2 exposures, which determines the spillover to stage-3 classification, and the multiplier effect derived from pre-existing customer-level exposure. Depending on the combination of our estimates for these two factors, our analysis shows that the increase in the non-performance ratio could be upwards of one percentage point. However, given the high degree of uncertainty characterizing the current economic climate, including over the path of interest rate increases, the impact on non-performance is difficult to quantify. In any event, non-performance should not translate into a significant increase in NPL coverage for two main reasons: (i) cautious front-loading of impairment provisioning by the banks in 2020 and 2021; and, (ii) the impact of the guarantees on the amount of losses incurred, as the banks’ exposure is ultimately limited to the percentage not covered by those public guarantees.

Introduction

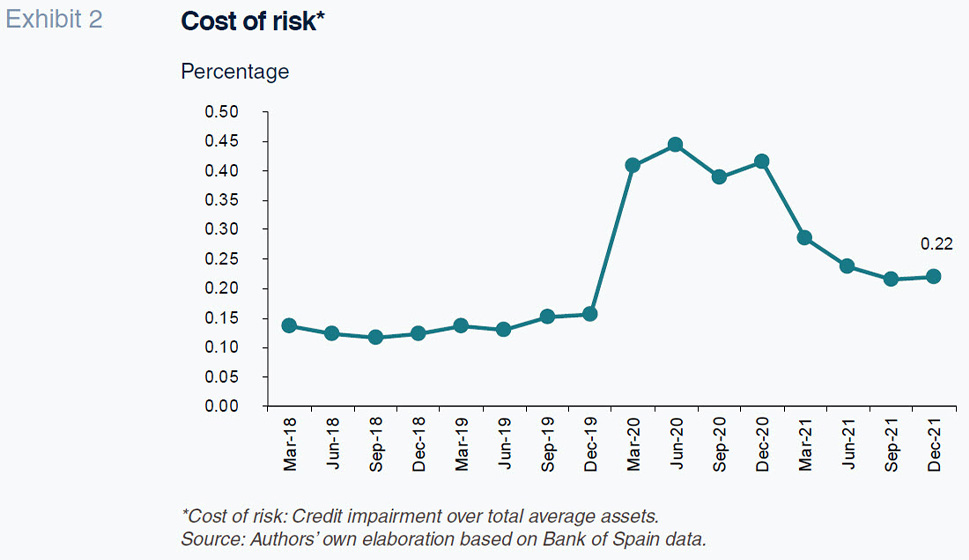

The downward trend in non-performing asset in the two years since the pandemic (flat or even slightly decreasing in a context of unprecedented economic contraction) is one of the headline paradoxes of the financial statements published by the Spanish and European banks. That has not, however, stopped the banks from setting aside significant provisions in anticipation of future impairment losses.

The fact that non-performance has been so contained is attributable to the easing of regulatory and accounting rules and business and sector support measures, most particularly the guarantee schemes rolled out by the government in the early months of the pandemic.

Those guarantees constitute an important lifeline for a significant number of businesses and self-employed professionals (nearly one million) thanks to the effort rolled out by the banks, in terms of both the speed with which they channelled credit to the various companies and their detailed analysis of the risks, a task in which the banks clearly had a vested interest given the fact that they have to assume a considerable percentage (20% to 30%) of the credit risk on the loans guaranteed.

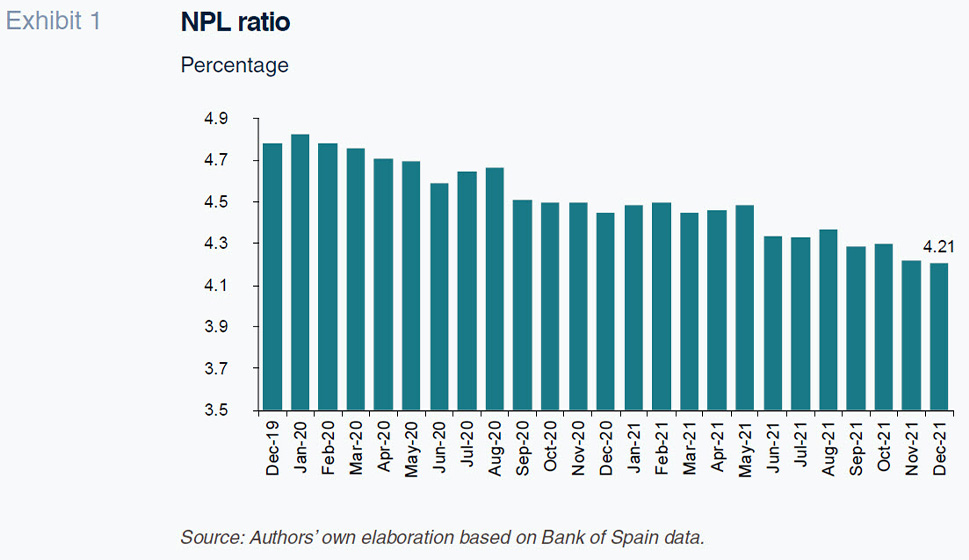

That exposure has barely materialised in non-performance to date, as a significant percentage of the loans are still covered by grace periods, initially granted for one year and later extended for another year. Just when those grace periods had nearly concluded, the government has announced a new extension agreement, for another six months, for the sectors and businesses most affected by the war in Ukraine, which will once again push back crystallisation of the unrealised impairment losses on the loans awarded under the state guarantee program. As a result, it is likely that we will continue to observe the dichotomy, depicted in Exhibits 1 and 2, between non-performance for accounting purposes and impairment allowances that has largely shaped the banks’ earnings performance, as already analysed on several occasions.

Guaranteed exposures: Leading indicator of impairment

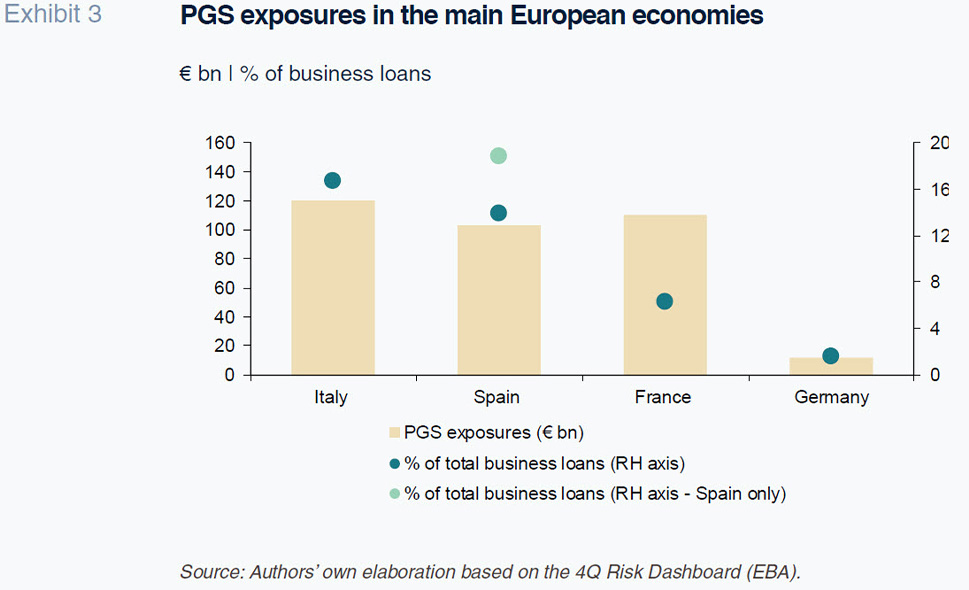

Within the wide range of measures taken to contain the effects of the pandemic on businesses and self-employed professionals, the state guarantee scheme played a significant role in Spain. It was the third-largest such programme in Europe in absolute terms (behind France and Italy) and the largest in relative terms. It is worth highlighting the fact that the volume of guaranteed loans outstanding in Spain represents nearly one-third of the total outstanding in Europe, and is nearly double the Spanish banking system’s weight in the overall eurozone system.

Given the quantitative materiality of the Spanish banks’ exposure to state guaranteed loans, we attempt to analyse that exposure in terms of risk categorisation in order to infer the scope for potential migration to non-performance, after more than two years at very controlled levels.

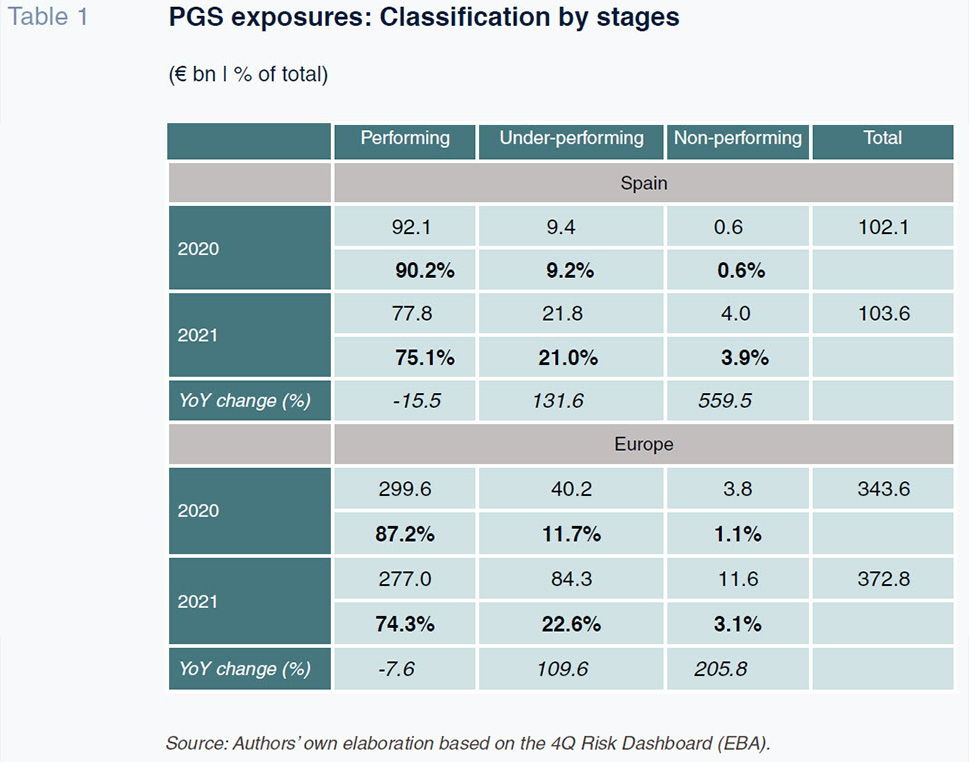

To do so, we use the information published in the latest Risk Dashboard released by the European Bank Authority (EBA), which classifies outstanding transactions secured by public guarantees by their riskiness in keeping with IFRS 9 rules: Stage 1 (performing); stage 2 (under-performing) and stage 3 (non-performing). The accompanying table provides that breakdown for the Spanish banks’ public guarantee scheme (PGS) exposure and for the European banks’ PGS exposure on aggregate.

The table reveals a very similar risk breakdown of PGS exposures at the Spanish and eurozone levels, suggesting very similar approaches in both instances on the part of the banks and/or their supervisors with respect to the classification of transactions as stage 2 (under-performing) exposures, the category where there is more room for discretion.

The table also provides the breakdown by stages at year-end 2020 and the trend over the course of 2021. Those figures reveal a significant increase in stage 3 exposures (which have tripled in Europe and more than quadrupled in Spain) and stage 2 exposures, which have increased by around 11 percentage points as a percentage of the total, (doubling) in Spain and Europe The increase in both stage 3 and, above all, stage 2 exposures probably reflects more stringent assessment by the banks of latent risk on those PGS exposures or, possibly, greater ‘pressure’ from the supervisory authorities to that end.

Simulation of the potential impact of the PGS on non-performance

Regardless of where the impetus is coming from, the transition to riskier stages has the potential to translate into growth in non-performance in the business loan segment in the future. And although the riskiness of PGS exposures in Spain and Europe is very similar, the potential impact on the banks’ non-performance is substantially higher in Spain on account of the higher weight of PGS exposures in total outstanding business loans.

Specifically, the Spanish banks’ 104 billion euros of PGS exposures at year-end 2021 represent around 15% of their aggregate exposure to the business lending segment on a consolidated basis, i.e., including loans extended by their foreign subsidiaries. The weight of PGS exposures over the total would be much higher (around 20%) if measured over the balance of credit extended by domestic entities of Spanish banking groups. By way of contrast, in the eurozone on aggregate, the 373 billion euros of PGS exposures at year-end 2021 represent just 7% of total outstanding loans to the business segment.

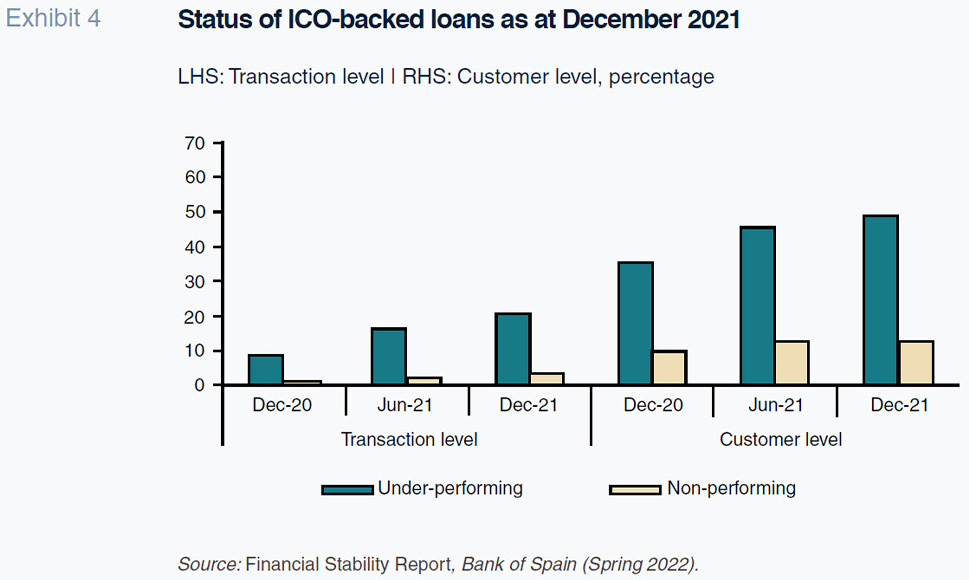

Focusing the analysis on the Spanish situation, an additional factor stands to multiply the potential impact of the impairment of PGS exposures on non-performance. The knock-on effect on other exposures to the same borrowers. That knock-on effect could be really major, perhaps twice as large in size, extrapolating the information published by the Bank of Spain in its April 2022 Financial Stability Report, as shown in Exhibit 4, gleaned from that report, which dates to year-end 2021.

That exhibit depicts the increase in the percentage of stage-2 exposures from 20% when analysed at the transaction level to nearly 50% when looked at from the customer perspective, i.e., factoring in all loans extended to customers that have received credit under the ICO scheme. Those figures suggest that the knock-on multiplier effect (customer level to transaction level) could be more than 2 times – that multiplier would be higher in the case of business loans relative to the self-employed segment, according to the data published by the Bank of Spain in its previous Financial Stability Report, using June 2021 figures.

Using the above data, and factoring in the significant weight of PGS exposures over total outstanding credit in Spain (around 20%), we can perform a sensitivity analysis with respect to the potential future impact on non-performance in the Spanish business lending segment, most of which is likely to materialise next year, or at the end of this year, insofar as borrowers from the sectors most affected, initially by the pandemic and now by the war, decide to make use of the option of extending the grace periods on their secured loans.

Based on a starting volume of around 22 billion euros of PGS exposures classified as stage 2, the impairment sensitivity analysis is shaped by two key inputs:

- The ratio of transition from stage 2 (under-performing) to stage 3 (non-performing), which we model at between 20% and 40%.

- The knock-on multiplier effect at the customer level, which we model at between 2x and 2.5x.

Taking these factors into account, we analyze the potential increase in non-performance in the business lending segment, from the current level of 5%.

According to our estimates, the increase in non-performance is highly sensitive to: (i) the percentage of operations in stage-2 that finally will be classified as stage-3, and (ii) the multiplier effect derived from customer-level exposure. Depending on the combination of the two drivers modelled, the increase in the non-performance ratio could be upwards of one percentage point. However, given the high degree of uncertainty characterizing the current economic climate, including over the path of interest rate increases, the impact on non-performance is difficult to quantify.

That said, a potential increase in non-performance should not translate into a significant increase in NPL coverage for two main reasons: (i) cautious front-loading of impairment provisioning by the banks in 2020 and 2021; and (ii) the impact of the guarantees on the amount of losses incurred, as the banks’ exposure is ultimately limited to the percentage not covered by those public guarantees.

References

BANK OF SPAIN (2021). Financial Stability Report, Autumn 2021.

BANK OF SPAIN (2021). Financial Stability Report, Spring 2022.

EBA (2022). Risk Dashboard, Q4 2021.

Marta Alberni, Ángel Berges and María Rodríguez. A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.