Spain’s household and corporate accounts: Two years after the pandemic

Although the recovery in Spanish GDP was somewhat less intense than initially expected in 2021, the recovery in employment was noteworthy and stronger than anticipated. Against that backdrop, two years after the onset of the pandemic, the financial health of Spain’s households remains solid, whereas that of the corporate sector has somewhat deteriorated.

Abstract: Although the recovery in Spanish GDP was somewhat less intense than initially expected in 2021, the recovery in employment was noteworthy and stronger than anticipated. Against that backdrop, the recovery in household income was more intense than that of the corporate segment that year. Household GDI ended 2021 2.8% below that of 2019, whereas corporate income remained 9.7% lower. The more pronounced recovery in the former was driven largely by public sector wages, as well as social benefits, which both rose above 2019 levels. Spain’s households once again registered excess savings in 2021, albeit below 2020 levels, earmarking nearly the entire volume of surplus savings towards housing investment. Despite that, household debt levels increased for the first time since 2008, albeit by a far lesser degree than the increase in Spanish corporate debt. That said, Spain’s companies too increased their leverage, despite generating, on aggregate, a sizeable net lending position, with companies most affected by the pandemic taking on additional borrowings largely to fund current expenses and ultimately, to some extent, eroding their overall financial health.

The surplus savings generated in 2021 were earmarked for home buying

Having contracted a resounding 10.8% in 2020 as a result of COVID-19, Spanish GDP recovered somewhat less intensely than initially expected in 2021, registering growth of 5.1%. The recovery in employment, however, was noteworthy and stronger than anticipated. Job destruction in 2020 was contained by the furlough scheme. Nevertheless, by the end of the third quarter of 2021, according to the Labour Force Survey, the number of job holders in Spain had surpassed that of the same quarter of 2019, despite the ongoing lag in the recovery in GDP. By the same token, the total number of Social Security contributors revisited pre-pandemic levels by around September, with the private sector contributor figure reaching the same milestone a couple of months later. However, the number of hours worked has yet to fully recover.

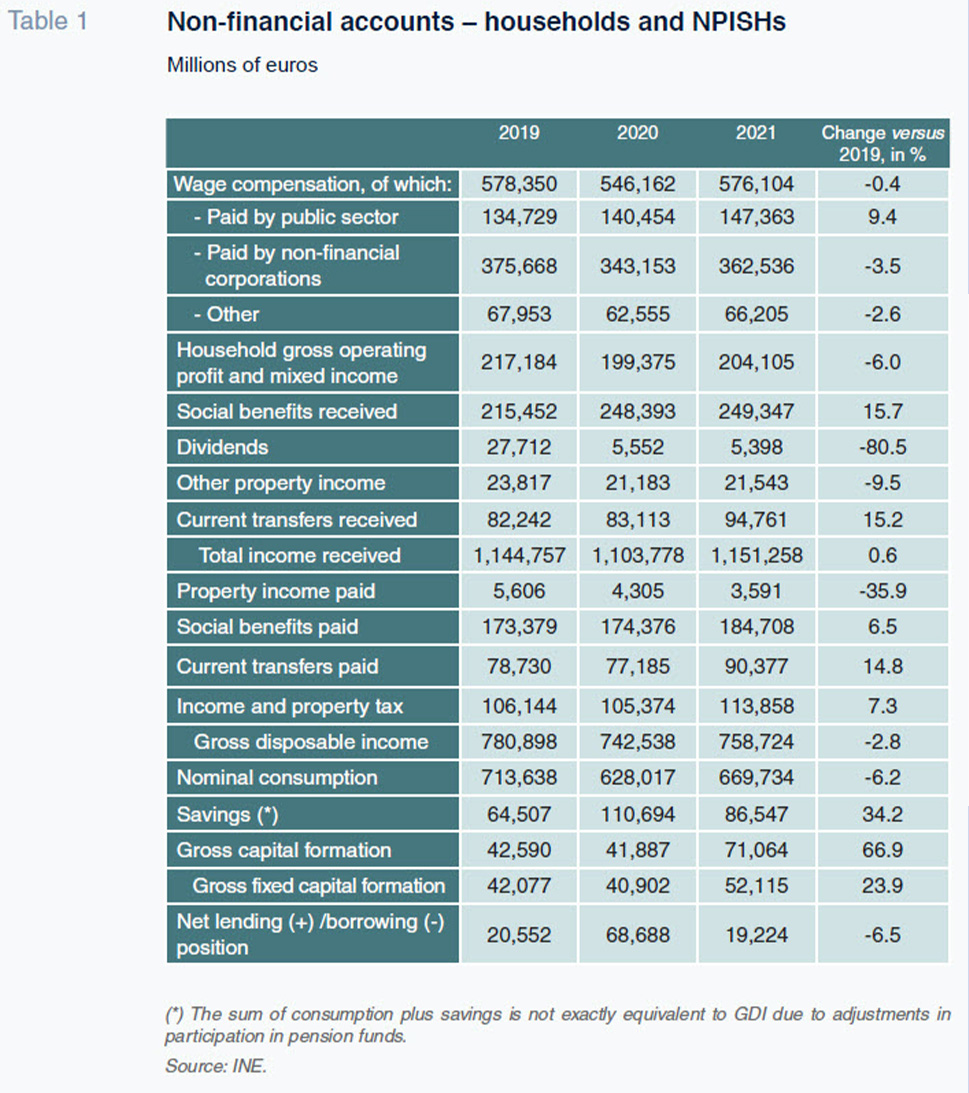

Against that backdrop, Spanish households’ gross disposable income (GDI) (and that of non-profit institutions serving households) increased by 2.2% in 2021, recovering 42% of the ground lost during year one of the pandemic, albeit with significant differences by source of income. Wage compensation increased by 5.5% – just 0.4% (or 2.25 billion euros) shy of 2019 levels. That recovery is largely due to the increase in wages paid by the public sector, which in 2021 were 9.4% higher than in 2019, shaped by growth in public employment, while the remuneration paid by corporations continued to lag that threshold by 3.5%. In contrast, recipients of capital income, specifically dividends, who saw that income contract by 80% in 2020, suffered an additional contraction of 2.8% in 2021, to 5.4 billion euros, compared to the 27.71 billion euros received in 2019 (Table 1).

The other sources of capital income sustained a decrease of 9.5% on aggregate over the two years in question. Social benefits, meanwhile, registered a slight increase in 2021, on the heels of sharp growth in 2020, so that in 2021 they were 15% above pre-pandemic levels, which is 33.9 billion euros more. Lastly, Spanish households’ interest payments declined further in 2021, to a record low since the series began in 1995.

Although household income had not revisited pre-crisis levels by 2021, the amounts paid by them in the form of social security contributions and income and property taxes were considerably above 2019 levels. Indeed, social security contributions were 11.33 billion euros higher and income tax was 7.71 billion euros higher. That meant a considerable increase in effective tax rates relative to taxable income for which it is hard to find a complete explanation, as there were no regulatory changes or tax rate increases to substantiate that phenomenon.

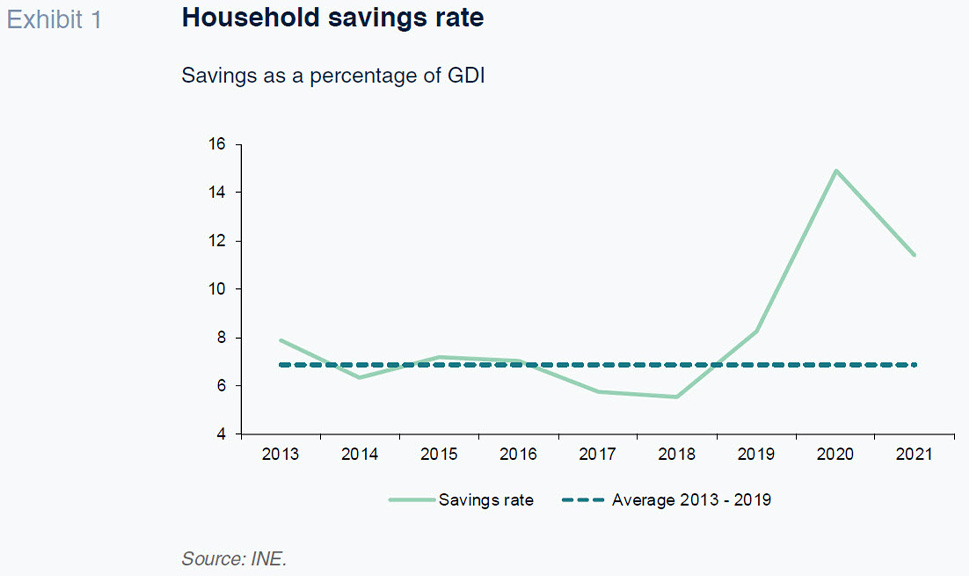

Nominal consumption rebounded by 6.6%, outpacing the growth in disposable income, driving a drop in household savings to 86.55 billion euros, down from the all-time high of 110.69 billion euros generated in 2020. Nevertheless, that figure continues to mark a very hight level by historical standards and the second highest reading since 2020. Savings as a percentage of GDI dipped from 14.9% in 2020 to 11.4%, which is well above the average of recent years, which means that households continued to generate surplus savings (Exhibit 1). In 2021, the population’s spending patterns had still not returned to normal. Recall that the interregional mobility restrictions remained in place until May and a number of other restrictions remained in place all year long. It wasn’t until late in the year that enough of the population was vaccinated to enable the more hesitant citizens to resume their social lives and pre-pandemic customs. Which is why the pool of forced savings stored away in 2020 increased even further in 2021 (Fernández, 2021).

If we assume that the desired savings rate is in line with the average recorded from the end of the last crisis until 2019, which is 6.9%, surplus savings set aside in 2021 amounted to around 34 billion euros, on top of the approximately 60 billion euros generated in 2020. Note, however, that not all of that surplus is undesirable as a portion may be justified by the prevailing uncertainty.

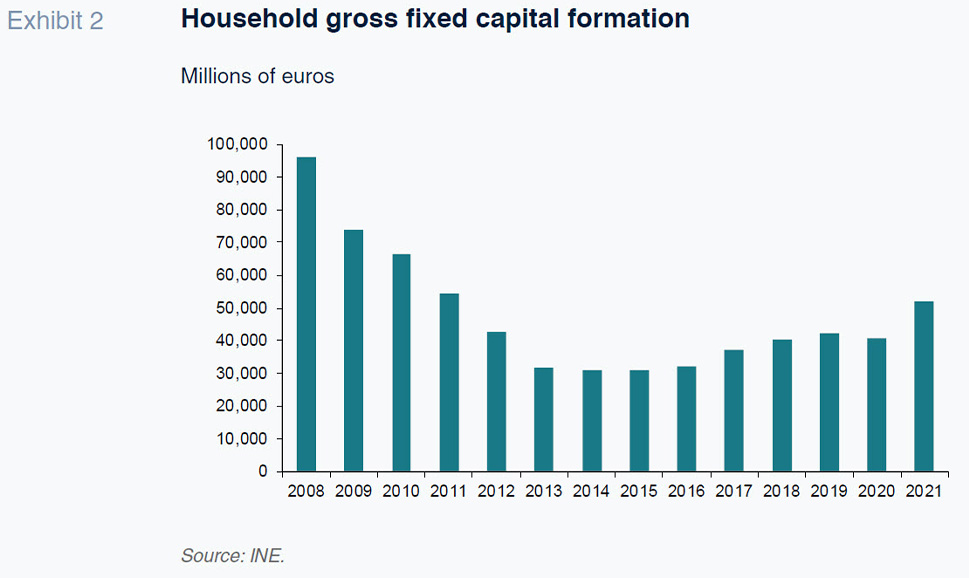

What was very different in 2021 compared to year one of the pandemic was what Spanish households did with their savings. In 2020, 40.90 billion euros was channelled into gross fixed capital formation, primarily real estate – in line with the level observed in prior years. However, in 2021, this figure rose to 52.12 billion, the highest since 2011 (Exhibit 2). Added to this are almost 19.0 billion in changes in inventories and acquisitions less transfers of valuable objects, an amount that is surprisingly higher than usual (given that in the entire historical series, households have never allocated more than 1.7 billion for this purpose). The remainder, 19.22 billion euros, or 1.6% of GDP, constitutes the net lending position generated by Spain’s households in 2021, which was earmarked to financial assets, mainly deposits and investments in shares and mutual funds. It is fair to say, in short, that the surplus savings generated in 2021 over the desired savings were earmarked entirely to increasing investment in housing, in addition to the aforementioned increase in changes in stocks and acquisitions, less transfers of valuable objects.

Elsewhere, unlike what we saw in 2020, in 2021, the household segment did not use their spare savings to repay debt; to the contrary, their borrowings increased in nominal terms, albeit very moderately (3.71 billion euros), for the first time since 2008. However, the ratio of debt to GDI actually decreased, to 92.8%. This leverage is a little above that of 2019, because GDI has still not fully recovered, but remains the lowest reading –except for 2019– since 2003.

Corporate income, still far from pre-pandemic levels

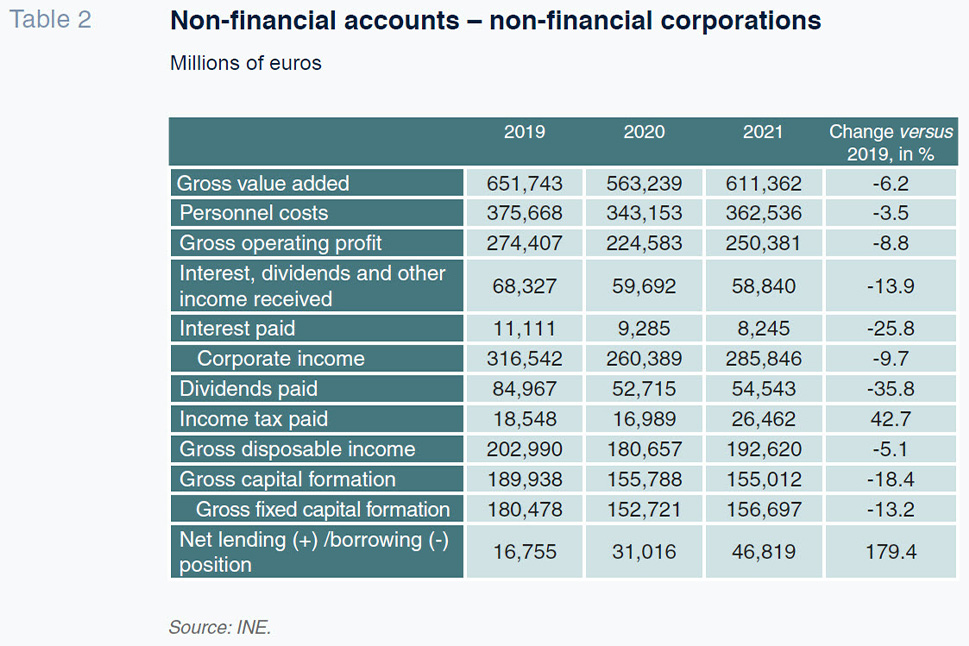

The non-financial corporations’ gross operating profit (GOP) made up half of the ground lost in 2020 in 2021, but still ended up 8.8% (24.4 billion euros) below the pre-pandemic figure. The capital income earned by these businesses, mainly dividends, contracted further, however, so that overall corporate income was nearly 10% below that of 2019. The dividends paid out increased slightly year-on-year, to 54.54 billion euros, but were still lower than those of 2019 by 30.42 billion euros (Table 2).

The Bank of Spain’s quarterly balance sheet statistics point in the same direction. Gross operating income increased by 23.6% in 2021, not fully making up for the contraction of 38.3% sustained in 2020, while the ratio of ordinary profit over net assets amounted to 4.7%, still well below the 6.8% attained in 2019. The Bank of Spain highlights the fact that the growth in energy costs curtailed the recovery in business margins in the more energy-intensive sectors towards the end of the year (Bank of Spain, 2022).

Despite the shortfall in operating profit by comparison with 2019, income and capital gains tax (mainly corporate income tax) increased by 43%, again implying, as in the case of the household segment, a significant increase in the effective tax rate borne by the business community.

The corporate sector’s gross savings – equivalent to disposable income, i.e., corporate income after the payment of taxes and distribution of dividends – increased to 192.62 billion euros, which is still 10.37 billion euros below 2019 levels. That volume of savings was more than what was needed to finance gross capital formation, giving rise to a surplus (net lending position) of 46.82 billion euros, which was used to purchase financial assets.

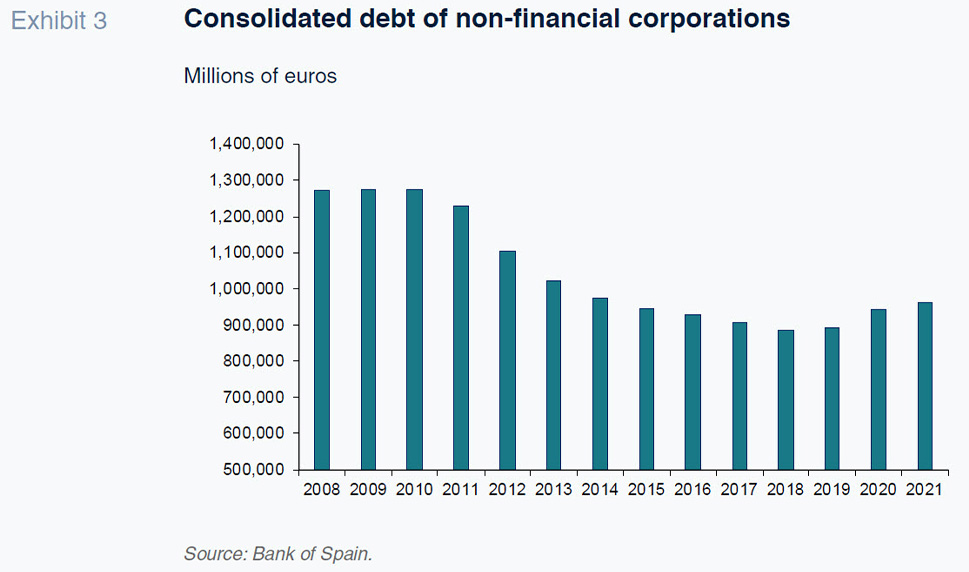

Despite having generated a comfortable buffer, corporate indebtedness increased, as was the case in 2020. That is attributable to the different impact of the crisis on the various sectors. The financial health of the companies operating in the sectors related with hospitality, tourism and leisure remained very delicate due to the persistence for much of the year of considerable restrictions and a still-limited recovery in their business volumes. In short, whereas some companies were able to generate a financial surplus, others were obliged to leverage up, with the proceeds earmarked, essentially, to current spending rather than productive investment. As a result, the volume of corporate borrowings at year-end 2021 was 70 billion euros above that of 2019 (Exhibit 3).

Conclusions

Two years on from the onset of the pandemic, the financial health of Spain’s households, taken as a whole, remains solid, whereas that of the corporate sector has deteriorated. The recovery in household income was more intense than that of the corporate segment in 2021. Household GDI ended 2021 2.8% below that of 2019, whereas corporate income remained 9.7% lower. The more pronounced recovery in the former was driven largely by the wages paid by the public sector, as well as social benefits, with both headings rising above 2019 levels.

Spain’s households once again saved in excess of the desired level in 2021, albeit by less than in 2020, and earmarked the entire balance of their surplus savings to financing the substantial growth observed in investment in housing. The latter is also responsible for the increase in household debt, for the first time since 2008, although by far less than Spain´s corporate sector. Indeed, Spain’s companies increased their borrowings, despite generating, on aggregate, a sizeable net lending position. That increase is attributable to the varying impact of the pandemic on different sectors. The companies most affected by the pandemic were forced to take on additional borrowings, not to finance capital expenditure, but rather to fund current expenses, implying, in addition to the partial recovery in earnings, erosion of their financial health.

References

María Jesús Fernández. Funcas