Youth housing affordability in Spain versus the EU

Spanish youth face significantly more difficulties accessing affordable housing than is the case in other European countries –a situation which has worsened in recent years. The main factor appears to be the shortage of rental housing, suggesting that policies should be geared towards promoting supply in that segment of the market, rather than acting in an untargeted manner or supporting demand.

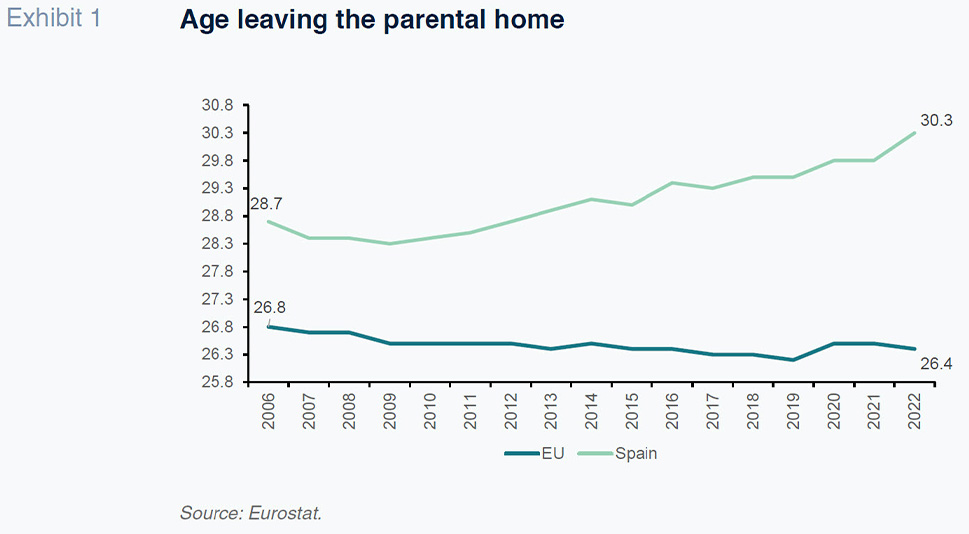

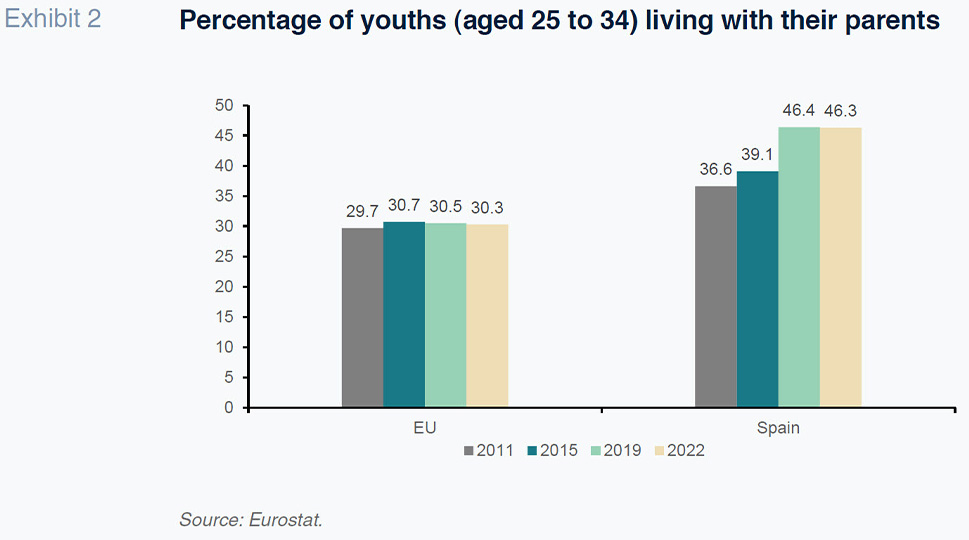

Abstract: The issue of housing affordability for youth is particularly pronounced in Spain and appears to have worsened in recent years. This may well be related to other socio-economic problems, such as the increase in the age at which young Spaniards are leaving home to above the age of 30, compared to an EU average of 26.4. The lack of a stock of an abundant supply of houses for rent at affordable prices is one of the biggest causes. Interestingly, despite the labour market challenges facing the Spanish youth, this does not appear to be the main factor affecting youth housing affordability in Spain. The solution to this problem therefore involves increasing supply, particularly in the rental segment. There are a host of international experiences to look at. Increasingly, given constraints to public treasuries for spearheading the required increase in supply via public sector investment, responses are taking the form of targeted incentives designed to provide young people with more affordable options.

Foreword

The scarcity of affordable housing is of grave concern for young people and their families and a central topic of public debate. The housing situation also has tangible consequences for labour force integration, mobility and integration into society in general (Causa and Pichelmann, 2020). A lack of housing opportunities for the youth –and its impact on the age at which young people leave their parental home– is also a factor behind the current low birth rate according to a number of studies (Stone, 2018).

The fact is that the age of emancipation in Spain is over 30, compared to 26.4 on average in the European Union (Exhibit 1). Moreover, that age is trending higher, whereas it is stabilising in the EU. The percentage of youths living with their parents has increased sharply, especially in the 24-35 age bracket, where over 46% were living at their parents’ home last year, up almost 10 points from a decade ago (Exhibit 2). The gap with the other large European countries is therefore widening.

The goal of this paper is to analyse young Spaniards’ standing in the property market by comparison with that of their peers in surrounding countries and take a brief look at some initiatives that could help alleviate the situation.

A stretched rental market: The key factor

The high volume of pent-up demand from young people unable to leave home, coupled with sustained price growth, points to supply scarcity as the main hurdle. Since the real estate bubble burst, home-building has been growing at a slower pace than demand for housing. Since 2015, house starts have been averaging around 75,000 units per year, compared to the nearly 120,000 new homes created annually during that same period. Moreover, new supply has tended to be concentrated in the home ownership segment, an adverse development for young people in particular.

An analysis based on Eurostat data suggests that the availability of an abundant pool of housing for rent at affordable prices –rent being young Europeans preferred route out of the parental home– is unquestionably the biggest problem in Spain. In the past, many young Spaniards were able to afford home ownership at a time when supply was rife and mortgages were readily available. At the start of this century, nearly six out of every ten youths were living in an owned home, with one out of four paying rent. After the bubble burst, however, supply collapsed and mortgages have become much harder to come by, so that today, just 30% of Spanish youths are living in their own homes.

[1] This trend has been exacerbated by the rise in interest rates, so that the youths living in an owned home mainly come from high-income households or have inherited money or property.

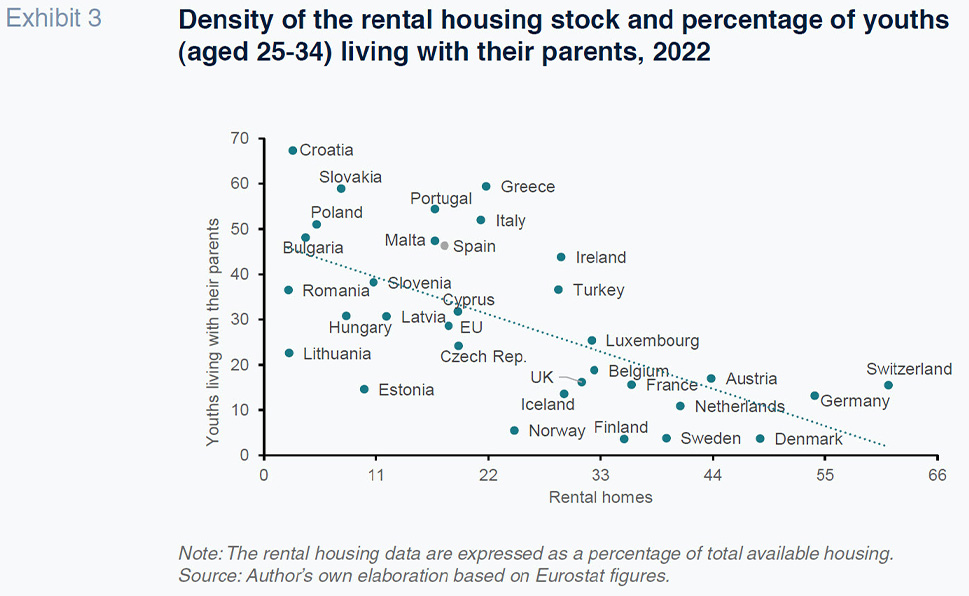

All of which explains the apparent correlation between the density of the stock of rental housing and the percentage of youths that has managed to move out from their parental home (Exhibit 3). In Scandinavia and Central Europe, where rental markets are relatively deep, the immense majority of young people can afford to move out. To the contrary, young people find it hard to leave parents’ home when the stock of rental housing is stretched, as is the case in Spain and other Southern European countries.

The shortfall of supply has translated into expensive rents. Four out of every ten tenants devote over 40% of their disposable income to paying rent, twice the European average. There is no breakdown by age bracket at the European level but the Spanish data show that the percentage of young tenants who bear excessive rents is even higher. In contrast, the percentage of people living in owned homes whose mortgage service costs are equivalent to over 40% of their disposable income is in line with the European average.

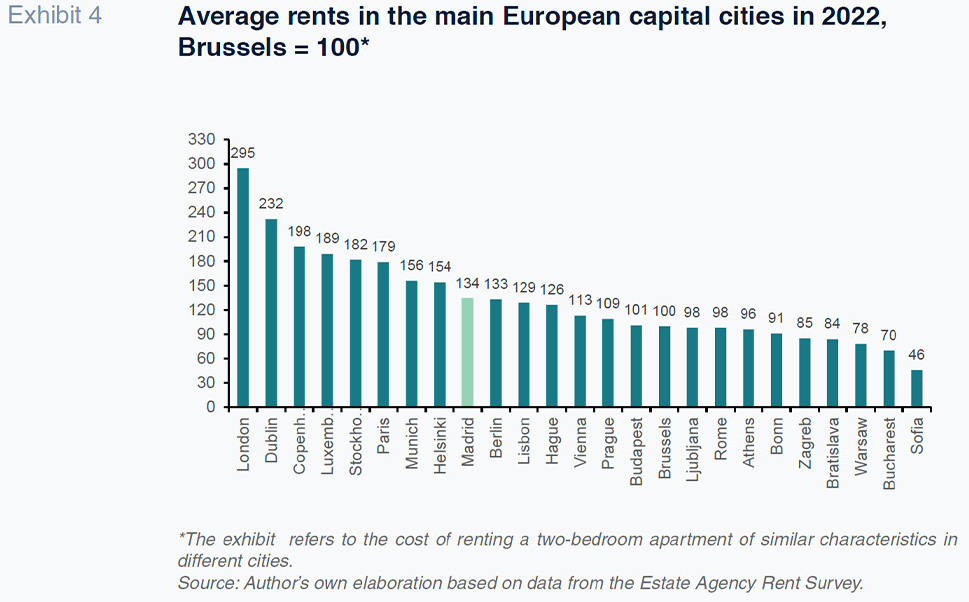

Reflecting the displacement of demand away from owner-occupied housing, rents have increased quickly in recent years: between 2015 and 2022, the average rent in Madrid increased by 39%, compared to an average of 26% in other European capital cities. The result is that as of today the average cost of renting a home in the Spanish capital is higher than in other major cities such as Berlin, Brussels or Rome (Exhibit 4). That gap would be even more pronounced if differences in purchasing power across the various cities were taken into account.

In some countries, governments subsidise access to the housing market either by placing a pool of social housing on the market or by providing direct assistance with rent payments. The most noteworthy examples can be found in the Scandinavian markets, France, Ireland and the UK. These policies, however, while justifiable in social terms, do not appear to be particularly effective at boosting the percentage of young people who can afford to move out from home. Indeed, social housing policies are useful from the distributional perspective but will only help address the aggregate scarcity problem if accompanied by a general increase in supply.

The labour market: A less important role

The labour market is another potential factor. Youth unemployment in Spain, which was close to the European average at the start of the century, shot up in the wake of the financial crisis. The gap narrowed during the subsequent years of economic recovery but never disappeared: in 2022, the unemployment rate among youths aged between 25 and 29 was more than 8.2 percentage points above the EU average, and in the 20 - 24 age bracket that gap stood at 13.3 points.

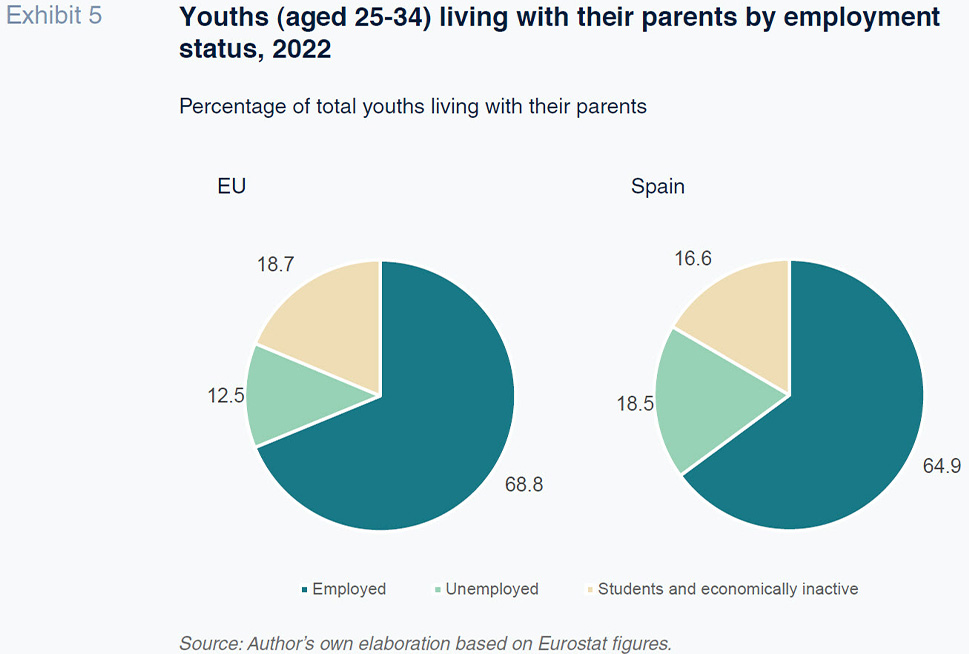

However, although finding employment facilitates access to housing, it does not appear to be the main factor. Nearly two out of every three people between the ages of 25 and 34 living with their parents have a job, a percentage that is only slightly below the European average (Exhibit 5). Moreover, most of these youths are working full time. Evidently, an increase in pay would allow them to assume the cost of housing (hence the importance of training, skills anticipation and job quality policies), all other factors remaining equal; however, if pay increases come across the board, the cost of housing would also increase, as the underlying issue is the scarcity of housing opportunities, i.e., supply.

In sum, in the last few years, the average age at which young Spaniards leave home has deviated further from the European average. The main cause lies with the scarcity of rental housing, a segment of the market that is crucial to young people being able to move out of home, judging by international experiences. The labour market, meanwhile, is a less significant factor in explaining the difficulties facing young people in accessing the housing market.

Implications for housing policy

Based on the above diagnosis, the solution to the housing problem therefore involves boosting supply, particularly in the rental segment. Public investment in social housing for rental is one option, albeit curtailed by two potential limits: (i) the need for rapid action, which may clash with the administrative procedures in place; and, (ii) government budget constraints (Causa and Pichelmann, 2020). Moreover, housing policy needs to be compatible with the incentives in place and consistent across the various levels of government.

The Canadian government’s Rapid Housing Initiative is a particularly relevant case in point. By speeding up the required red tape and creating a one-stop application window through which local governments could obtain financing, the programme managed to create more than 10,000 additional units in just six months.

[2]

This type of initiative, cited as a case study by the OECD, is particularly useful for providing a housing solution for vulnerable groups, including youths living in precarious situations. However, for home-seekers with a certain level of income, such as the young people stuck living with their parents despite being in full-time work, the initiatives need to be targeted at making the market work better so as to respond to their needs.

This type of initiative, cited as a case study by the OECD, is particularly useful for providing a housing solution for vulnerable groups, including youths living in precarious situations. However, for home-seekers with a certain level of income, such as the young people stuck living with their parents despite being in full-time work, the initiatives need to be targeted at making the market work better so as to respond to their needs.

This consideration, coupled with the constraints on public spending, is why the role of government in new housing investment is diminishing in most European markets. Instead, governments intervene through a set of market initiatives. Firstly, in some countries including Germany, the UK and Ireland, the strategy has been to multiply the concession of land for private construction, subject to criteria such as reserving a percentage of the new builds for rental housing, for example, the re-zoning initiatives in Stuttgart, London and Dublin. (Scanlon, 2017). In Switzerland, some cantons are providing zoned land at below market prices or under long-term lease arrangements in order to reduce investment costs and stimulate the supply of rental housing. In all instances, the direct cost for the public coffers is small, although the programmes entail implicit assistance by providing developers with building permits on advantageous terms.

Secondly, some cities are offering soft loans and other forms of assistance targeted exclusively at the construction of social rental housing. Examples include Paris and Vancouver (the “Rental 100” programme). These measures can be complemented by investments in public infrastructure in an attempt to stimulate construction and channel housing that is currently vacant on account of its distance from the major city centres onto the market. Studies show, however, that this policy, in addition to constituting a direct cost for the public coffers, might crowd out the supply of unsubsidised rental housing (refer, for example, Del Pero et al., 2016). In light of this displacement effect, it may be preferable to focus public policy on the development of rental housing in general (neutral supply incentives) and to subsequently offer specific assistance to disadvantaged youth (select demand support).

Thirdly, regulatory initiatives have also been launched. In response to the pressures posed by tourism, some European cities have opted to limit the supply of holiday rental alternatives in order to nudge those properties back onto the free market. Others exact levies from vacant houses with the same aim. These incentives may help boost options for young people, particularly in tourist-saturated markets. And indeed some studies indicate that these forms of intervention can be effective at the local level, (García López et al., 2020) though their impact at the aggregate level may be limited.

Finally, these international experiences suggest that in Spain, housing policies targeted specifically at the rental segment would be particularly cost-effective at helping young people move out of their parental home. Such an approach would unquestionably prove more effective than multiplying the guarantees and aid provided to home-buyers, albeit requiring cooperation among the various levels of government, especially the regional and local authorities, where responsibility for housing policy implementation is largely concentrated.

Notes

It is also worth noting the reforms of 2012 which did away with the mortgage tax break whereby borrowers had been allowed to deduct 15% of their (primary residence) mortgage costs for income tax purposes.

References

CAUSA, O. and PICHELMANN, J. (2020). Should I stay or should I go? Housing and residential mobility across OECD countries.

Economics Department Working Papers, No.1626. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

https://one.oecd.org/document/ECO/WKP(2020)34/En/pdf

DEL PERO, S., WILLEM, A., FERRARO, V. and FREY, V. (2016). Policies to Promote Access to Good-Quality Affordable Housing in OECD Countries.

OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper, 176. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

GARCÍA-LÓPEZ, M. Á., JOFRE-MONSENY, J., MARTÍNEZ-MAZZA, R. and SEGÚ, M. (2020). Do short-term rental platforms affect housing markets? Evidence from Airbnb in Barcelona.

Journal of Urban Economics, Volume 119.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2020.103278SCALON, K. (2017).

Making the most of build to rent. London School of Economics.

https://www.lse.ac.uk/business/consulting/reports/making-the-most-of-build-to-rentSTONE, L. (2018).

Higher Rents, Fewer Babies? Housing Costs and Fertility Decline. Institute for Family Studies.

https://ifstudies.org/blog/higher-rent-fewer-babies-housing-costs-and-fertility-decline

Raymond Torres. Funcas