One year of rate increases: Impact assessment

Monetary policy remains immersed in an intense battle to stem inflation, manifesting itself through a quick succession of interest rate increases and consequently raising eurozone borrowing rates across the board. Credit has already contracted, and the cost of debt has increased, but the duration of the tightening cycle remains unclear as monetary authorities have signalled that their policy approach remains conditional upon the path of inflation.

Abstract: At least two generations of labour market participants had never experienced positive real interest rates and were paying very low rates on their borrowings until just over a year ago. Today, monetary policy remains immersed in an intense and complex battle to stem inflation. The most obvious consequence has been a quick succession of interest rate increases. In the eurozone, the price of money has been rising for over 18 months, significantly increasing borrowing costs for households, companies, and governments. Credit has already contracted substantially, and the cost of debt has increased. Indeed, the increased cost of money has driven a slowdown in mortgage flows to year-on-year rates of growth of 2.5% as of July 2023. At the same time, however, the banks’ pre-tax earnings over average total assets had increased from 0.8% to 1.1% in the first quarter of 2023 and the spread between asset and liability rates had increased by just 0.1pp to 1%. Lastly, the cost of public debt has increased considerably. Since 2021, the cost of issuing 3-year bonds in Spain has increased by 3.75pp, while the cost of issuing 10-year paper has increased by 3.16pp. As acknowledged by the heads of the central banks themselves, it is unclear how long it will take for these policies to have their intended effects. The monetary authorities’ key message is that the approach has to remain conditional until uncertainty around inflation dissipates.

Foreword

Although the Federal Reserve embarked on the process of unwinding its expansionary policy earlier, in the eurozone rates were first increased in July 2022, kick-starting what some dub monetary tightening and others simply call normalisation. That is when the European Central Bank (ECB) began to abandon its ultra-lax policy in order to tackle inflation. One year on, in July 2023, it increased its key rates further, to 4.25%. At its July meeting, the ECB signalled a potential end to the rate tightening cycle. Its president, Christine Lagarde, said that the September meeting could be key to determining whether rates are increased further, or the ECB decides to put additional tightening on ice. The Governing Council of the central bank decided to raise interest rates by 25 basis points in its meeting of 14 September. In her statement, Lagarde said, “We will continue to follow a data-dependent approach to determining the appropriate level and duration of restriction. In particular, our interest rate decisions will be based on our assessment of the inflation outlook in light of the incoming economic and financial data, the dynamics of underlying inflation, and the strength of monetary policy transmission.”

In any event, just a few weeks earlier, at one of the major international events in the economic calendar, the Jackson Hole Symposium organised by the Kansas City Federal Reserve between 24 and 26 August 2023, the heads of both monetary authorities mentioned some of the main difficulties facing monetary policy at present, which cloud the path to be taken over the coming months. Jerome Powell emphasised that despite significant monetary policy tightening over the past year and the fact that inflation has fallen back from its peak, price growth remains too high. He said that the Fed is prepared to increase interest rates again if necessary and keep its policy restrictive until it is clear that inflation is moving sustainably down towards its objective. In his words, the Fed is committed to achieving and sustaining a monetary policy stance that brings inflation down to the targeted level over time. However, Powell acknowledged the challenge in determining when that stance has been achieved and referred to current real interest rates as restrictive. He also said it is not possible to identify with certainty the neutral rate of interest (that which is theoretically compatible with full employment), adding uncertainty about the precise level of monetary policy restraint. That assessment is further complicated by uncertainty about how long it will take for monetary policy to affect economic activity and inflation.

Christine Lagarde, for her part, stressed that the shifts characterising the current environment could change the type of shocks we face and their transmission through the economy. She pinpointed three key elements of robust policy-making in this setting: clarity, flexibility, and humility. Firstly, she emphasised the need for clarity around targets, assuring that price stability is essential for fostering investment. However, to achieve these goals, flexibility is crucial. Lagarde said it was not a good idea to rely exclusively on models estimated using old data or to focus too much on current data. In their stead, she suggested constructing policy frameworks that capture the prevailing complexity.

Lastly, she underlined the importance of humility, acknowledging the limits of current knowledge and what policy can achieve. She said it is essential to talk about the future in a way that reflects the prevailing uncertainty in order to maintain credibility with the public.

Meanwhile, economic developments in Spain are sending mixed messages in terms of tackling this monetary paradigm. On the one hand, although inflation rebounded to 2.6% in August (with core inflation at 6.1%), it remains well below the eurozone average (over 5%), so that the interest rate increases are proving even more restrictive for the Spanish economy. Against this backdrop, in this paper we attempt to answer certain questions that are pertinent after over a year of interest rate increases.

Are current rates high by historical standards?

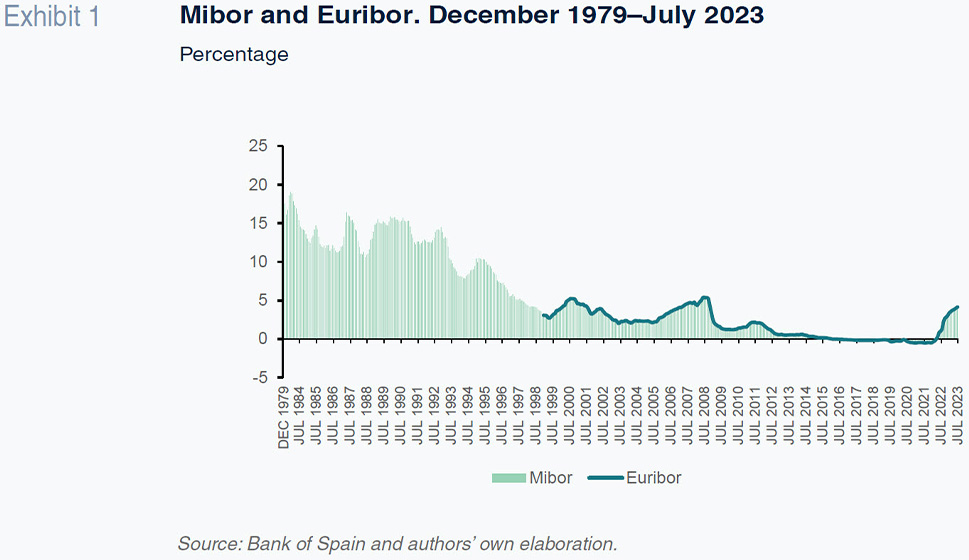

It is common to see headlines along the lines of “interest rates rise to historical levels” in the press. While that statement is true, it needs qualifying. The most commonly used benchmark rate, Euribor, was created in 1999 as part of the single currency process. A longer-running comparable benchmark for Spain, which has traded parallel to Euribor since 1999, is Mibor, for which the series dates back to 1979. As shown in Exhibit 1, the interest rates used as the benchmark for pricing mortgages topped 15% during the 1980s and some of the 90s. However, considering only the timespan of the eurozone and single currency, current interest rates are high, trading at close to the peak observed right before the onset of the financial crisis, when they were at over 5%.

Behavioural factors are also important in the current context. At least two generations of labour market newcomers had yet to experience positive real interest rates and were paying very low rates on their borrowings until very recently. The real anomaly is not so much the level reached in the price of money but rather how quickly that level has been reached.

What has happened to lending activity, especially home loans?

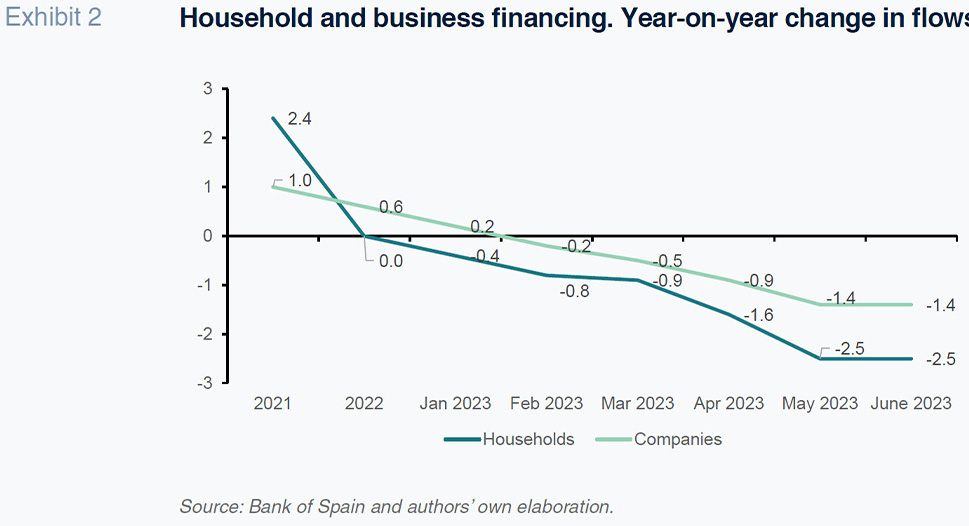

Higher interest rates have an obvious impact on the cost of mortgages. Taking a long-term perspective, growth in credit has been relatively slow for years. One might well ask how it is possible that financing for households and companies (starting from their demand) did not register stronger growth during so many years of low rates. Much of the answer lies with the transition from the financial crisis until almost 2019, when annual flows of new loans barely increased or actually contracted, as the private sector deleveraged steadily in the wake of the financial crisis. Then the pandemic broke out and households became conservative, while companies took advantage of the expansionary financing policies designed to mitigate the effects of the lockdown. As shown in Exhibit 2, in recent years, especially since official rates began to increase, growth in credit has been slowing, reaching negative levels in June 2023 (-1.4% in business lending and -2.5% in household lending). It is also worth highlighting the monthly trend (not shown in the exhibit) in mortgage lending between January and June 2023, marked by contractions of 0.6%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 1.9%, 2.3% and 2.5%, respectively.

How have the banks been affected?

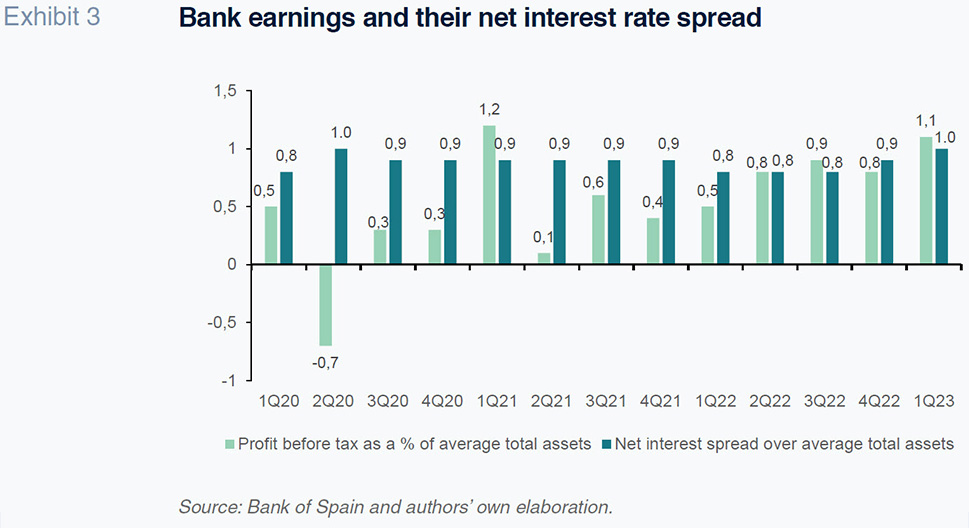

Another common topic of debate since rates started to rise has to do with the banks benefitting from the situation. A longer-term horizon is perhaps the best perspective for analysing this matter. The reduction in interest rates to below zero since the financial crisis can be justified from a theoretical standpoint. In practice, however, it evidently created a series of distortions and dysfunctions across several dimensions of the banking business with the potential to affect the broader economy. It has also been shown that if rates are left low for a long period of time they generate a significant structural profitability problem for the banks. The COVID-19 pandemic and the central banks’ response further fuelled the market’s expectation that interest rates would remain negative for even longer than anticipated before the pandemic. In the end, in little more than one-year rates have actually increased to their highest levels in over two decades. That has enabled the banks to carry out their intermediation function in a more reasonable margin environment. Nevertheless, lending activity has stagnated and profit before tax relative to average assets has inched just 0.3pp higher, to 1.1% in the first quarter of 2023 (most recent figure available) (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3 also shows how the spread between the rate earned on loans and paid on liabilities remained almost flat at 0.9% between 2020 and 2022, increasing by just 0.1pp to 1% in the first quarter of 2023.

How are the securities markets dealing with current interest rates?

Rising interest rates can have a significant impact on the markets in the case of share prices. A higher rate can affect companies’ future earnings growth, weighing on economic growth. In 2022, when inflation was rampant, the markets performed negatively in general, notching up losses across multiple portfolios. Shares that were trading at high price-to-earnings multiples (P/Es), primarily tech and secular growth stocks, corrected the hardest in 2022.

Another challenge created by high interest rates lies with the fact that other financial instruments, such as bonds and certificates of deposit, offer more attractive returns. Investors may prefer not to invest in stocks if they believe that the value of the companies’ future earnings is less attractive by comparison with bonds offering compelling yields. This pattern is unfolding at different speeds in different jurisdictions.

Another factor is the cost of debt. Companies that need to refinance will have to pay more than before, eroding their future profits. However, many companies issued bonds in 2020 and 2021 taking advantage of low rates at the time so that they are not yet facing higher borrowing costs.

Lastly, in the wake of the rate increases carried out already in 2023, the outlook for the stock markets is uncertain. The markets performed relatively well in the first quarter but have displayed greater hesitation since then. The trend since the summer is unclear. What happens next will depend on the direction monetary policy takes and the extent to which the economies withstand the restrictions imposed by the central banks. If inflation takes longer than expected to rein in, expectations could deteriorate.

Impact on public debt

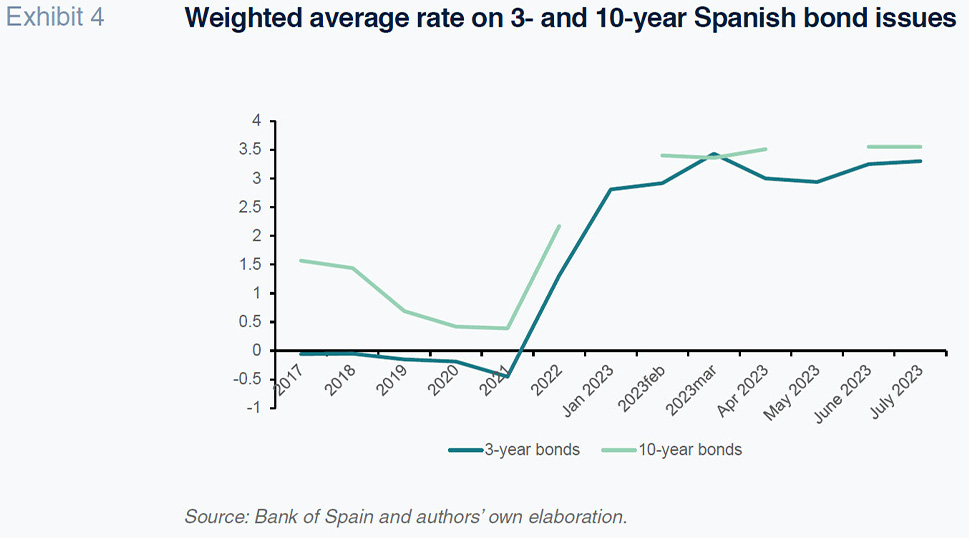

In the debt markets, especially the public debt markets, borrowing costs have risen sharply. However, even more so than in the corporate sector, the various public treasuries, including Spain’s, took advantage of the years of low rates to refinance their debt and extend their maturity profiles at low and even negative rates. Medium-term, however, caution is warranted. As shown in Exhibit 4, the weighted average cost of debt has increased considerably in recent months. The rate on 3-year Treasury bonds has increased gradually from -0.4% in 2021 to 3.3% by July 2023. Over the same period, the rate on 10-year bonds has jumped from 0.4% to 3.4%.

Conclusion: Will we see further rate increases?

The monetary authorities are signalling two key messages at present. The first is that, although things have improved, inflation remains far from being anchored at 2%. The second is that it is currently hard to provide guidance around decision-making. The central banks’ approach is more conditional than ever. One of the main reasons being that the central banks admittedly do not know precisely how long it will take for their policy decisions to take effect. The idea taking shape is that we are nearing the end of rate tightening but that until inflation is under control, fresh increases in the price of money cannot be ruled out.

Santiago Carbó Valverde. University of Valencia and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas