The impact of the pandemic on the shadow economy: Known knowns

An interpretation of recent indicators claims that policy responses such as the furlough scheme and changes in individuals’ and firms’ behaviours driven by the pandemic, such as increased reliance on electronic payments, have significantly reduced the size of the shadow economy and tax evasion in Spain. However, a more prudent perspective advises deepening the analyses and confirming this structural change with data for an extended period.

Abstract: Analysis appears to support a favourable evolution of the tax revenue-to-GDP figures and the estimates regarding the size of the shadow economy in Spain. The shock induced by the pandemic led to a spike in inflation, which drove growth in tax receipts to a level that apparently outpaced inflation and real economic growth, albeit the evidence is far from conclusive. The gap in the tax burden with respect to the EU-27 average in 2019 has closed by half. This gap originated from a plethora of special tax treatments and a relatively larger shadow economy and level of tax fraud. Related to tax fraud, indeed, it is possible that the rise in electronic payments during and after the pandemic (perpetuated by the decrease in cash payments during this period) has made tax evasion more difficult, helping to increase VAT collections and changing individuals’ behaviour. As well, the pandemic may have helped bring about a decrease in the number of workers without a contract and not paying income taxes and social contributions. Thus, given that the regime for special tax treatment has not changed substantially, it has been deduced that resolution of the latter issues is responsible for reducing the gap. That said, once again, on this point, the empirical evidence is far from conclusive. Moreover, the surprising and starkly contrasting pictures painted by the various calculations made using VAT, and the divergence in estimates about the size of the shadow economy, which place Spain both above and below the EU-27 average, clearly illustrate the need for more rigorous analysis over a larger time series after the pandemic. Such an effort would additionally serve to provide the foundations for building a more ambitious strategy for situating Spain within the first quartile of the EU-27’s best-performing member states in terms of efforts to combat the shadow economy and tax fraud.

Shadow economy and tax fraud: A few considerations [1]

The shadow economy and tax fraud have been the focus of public debate in Spain of late. The inclusion of component number 27, “Measures and actions to prevent and combat tax fraud”, in Spain’s Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan (RTRP) involves a series of commitments to the European Union around this issue and helps explain its recent prominence. The argument is that the pandemic modified habits and conduct in such a way as to help reduce the scale of both problems in Spain. Since 2020, Spain has converged towards European averages in terms of the incidence of these issues. The main purpose of this paper is to assess the accuracy of this claim using available estimates and calculations, paving the way for addressing the level of delivery of item 27 of the RTRP in an upcoming article.

The shadow economy and tax fraud are intricately related concepts, but they are not synonymous. The differences between them are not insignificant. The shadow economy involves hiding economic activities in general, while tax fraud consists of deliberately disobeying tax laws, which does not necessarily involve the existence of prior or concurrent informal economic activity.

It is hard to quantify the shadow economy precisely because its participants work to stay out of the spotlight implied by registers and statistics. In general, the preferred estimation methods take an indirect approach, using macroeconomic variables that are correlated with the informal economy. The most reliable are the monetary approach, the so-called MIMIC model, and the analysis of discrepancies between official statistics and estimates gleaned from other sources (Lago Peñas, 2018).

Estimates of tax evasion, meanwhile, involve two main approaches. On the one hand, we have papers that focus on fraud in a specific tax or tax source. These studies use ad-hoc methodologies that depend on the characteristics of the tax in question and the information available. Their main drawback is that they provide partial estimates and fail to quantify tax fraud as a whole. That is why it is also common to see a different approach. Essentially, it focuses on the shadow economy, examining its impact on tax revenue in a very simple way: it assumes that the taxable income not taxed is proportionate to the size of the shadow economy and applies the average effective tax rate observed in the formal economy to that base. The validity of this method depends on two key assumptions: (i) that the size of the shadow economy is a good proxy for the amount of taxable income on which tax is avoided; and, (ii) that the average effective tax rate observed in the formal economy is the right rate to apply to that tax base. Both assumptions should be taken with considerable caution. This is so because they ignore the tax fraud that takes place outside of the shadow economy; because some of the shadow economy would disappear if forced into the formal economy due to the resulting increase in costs; and because the average tax rate applicable to the taxable income corresponding to the informal economy likely should be lower than that of the formal economy.

The rest of this paper is structured into four sections. The next section analyses the interpretations and perceptions around the impact of the pandemic on the shadow economy. Subsequently, we take a look at what the most recent estimates and calculations tell us. The following section focuses on the so-called tax residuals and the effects of inflation on tax revenue. Lastly, we outline our main conclusions.

Impact of the pandemic on the shadow economy: Interpretations and perceptions

The draft budget for 2023 published in October 2022 (Government of Spain, 2022), claimed that the deployment of an income protection system of unprecedented reach and size has had the positive effect of formalising some of the shadow economy, leading to a better-performing labour market and an improvement in the structural public deficit. Specifically, the furlough scheme, the extraordinary income support for the self-employed, and the minimum income scheme are said to have brought people who used to work in the informal economy back into the fold of the formal economy. Comparing the data from the Labour Force Survey and Social Security contributors (general regime), the Spanish government calculated that the measures taken during the COVID-19 crisis had brought around 285,000 contributors back into the Social Security system by the summer of 2022: 250,000 employees and 35,000 self-employed workers. The National Office of Foresight and Strategy has repeated this argument on several occasions.

By April 2023, in presenting the Stability Programme Update, 2023-2026 (Government of Spain, 2023), the emphasis shifted to the impact on tax revenue. The assertion was that the effort to combat tax fraud and reduce the shadow economy was responsible for the increase in the ratio of tax receipts over GDP. Specifically, the government underlined the importance of the shift in tax morale as a result of the COVID-19 crisis because the protection scheme deployed by the government through measures such as the furlough scheme did not encompass the shadow economy, and highlighted the changes in conduct derived, for example, from the growth in card payments relative to cash payments.

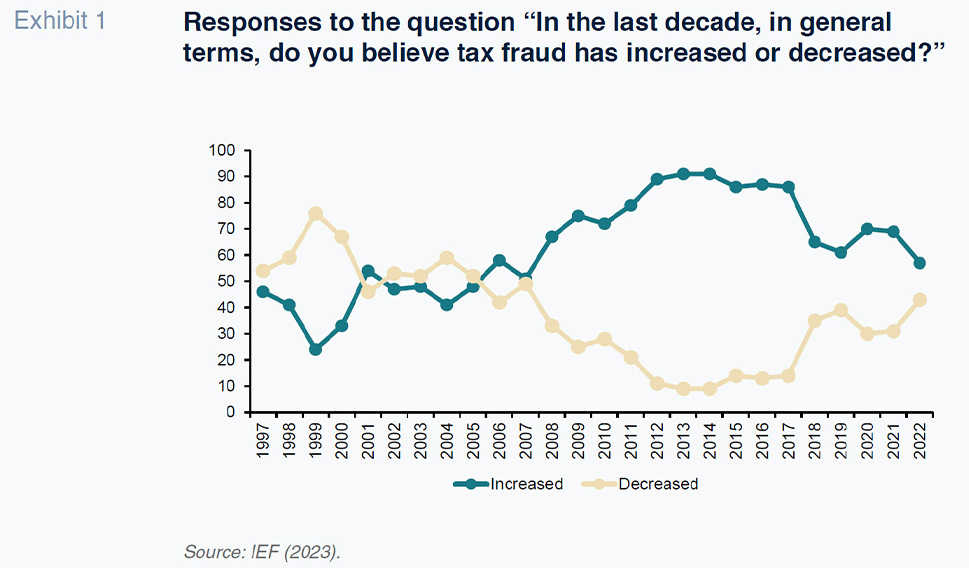

To get an idea of how citizens’ perceptions of these issues have evolved in recent years, the best source is the Fiscal Barometer which the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IEF, 2023) has been publishing for over 25 years. Exhibit 1 depicts the trend since 1997 in respondents’ answers to the question as to whether they believe tax fraud has increased or decreased in the past decade. Note that the surveys in respect of 2022 were carried out between 30 June 2023 and 27 August 2023. Citizens’ perception of the incidence of tax fraud deteriorated sharply between 2007 and 2017. After that, the situation improved, a process interrupted at the height of the pandemic (2020-2021). In 2022, the situation reverted, for the first time in 15 years, to the snapshot from before the Great Recession. This confirms, therefore, that citizens’ perception of the scale of tax evasion has improved in the wake of the pandemic, albeit remaining far from the perception observed at the end of the 1990s, when the people who thought that compliance was improving far outnumbered the pessimists.

Estimation of the shadow economy and tax fraud for 2020-2023

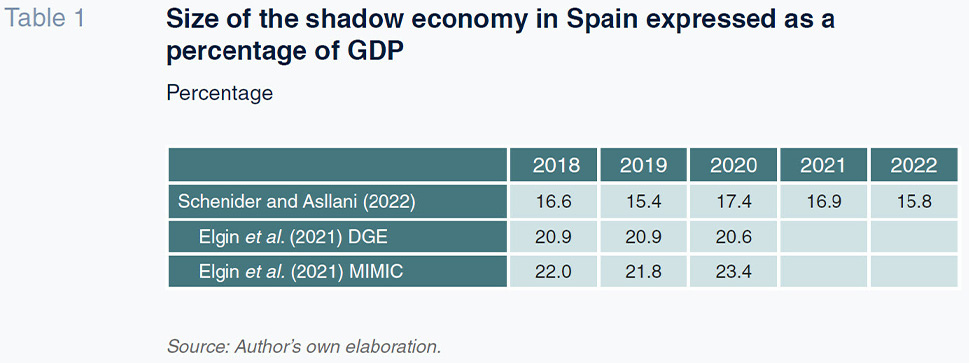

Starting with the shadow economy and the international analyses that include Spain along with other countries, we would highlight Schneider and Asllani (2022), whose calculations coincide with those estimated previously by Schneider (2022) using the MIMIC model, and the estimates by Elgin et al. (2021), which feed into the World Bank’s informal economy database [2]. Table 1 reproduces the values available for 2018-2022. The World Bank data feature the results obtained using two alternative methodologies: a dynamic general equilibrium (DGE) model and the MIMIC method.

Taken together, the results shown in Table 1 indicate growth in the shadow economy during year one of the pandemic and shrinkage in the following years. The figure provided by Schneider and Asllani for 2022 (15.8%) is 1.5 percentage points below the EU-28 average (17.3%), Spain’s best performance during the time series analysed, which starts in 2002.

Turning to tax fraud, we have the VAT compliance gap estimates of CASE et al. (2023). Note that the VAT compliance gap is mainly attributable to evasion but is also the result of tax receipts lost on account of bankruptcies, administrative errors, and tax optimisation strategies. The results are extraordinarily positive for Spain and hard to fit with other findings. By this measure, Spain is the third most compliant country in the EU-27. Between 2020 and 2021, the gap went from a little over 5% of potential receipts under the legislation in effect in 2020 to just 0.8% in 2021. This improvement can be seen across all countries, except Denmark and Sweden, and the authors attribute it to factors such as improvements in tax management, the growth in online commerce and the reduction in cash payments.

Here it is worth referring to Pappadá and Rogoff (2023), who use a new VAT-based methodology dubbed EVADE to estimate the shadow economy. In clear contrast to CASE et al. (2023) estimates, Spain ranks third on a list of 21 European countries ordered from biggest to smallest informal economies. The explanation for this discrepancy lies very probably with the other concept computed by CASE et al. (2023): the VAT policy gap, which reflects the impact of policy decisions around tax rates and tax bases. Spain is, together with Greece and Italy, one of the countries that foregoes the most revenue due to decisions about rates and bases, in addition to the non-application of VAT in the Canary Islands, Ceuta and Melilla. The EVADE method is not designed to isolate this dimension, which explains why Greece, Italy and Spain are the countries with the largest informal economies according to the estimates compiled by Pappadá and Rogoff (2023).

The surprising and starkly contrasting pictures painted by the various calculations made using VAT, and the divergence in estimates about the size of the shadow economy, which place Spain both above and below the EU-27 average, clearly illustrate the need for further analysis. That is the only way to accurately tell what is really going on and identify the underlying mechanisms. We return to this point in the last section of this paper.

Tax residuals and the impact of inflation in Spain

Tax revenue has been growing sharply in Spain since 2019. Using Eurostat data, the weight of tax and social security contributions over GDP in the EU-27 as a whole inched from 41% in 2019 to 41.1% in 2022. In contrast, it jumped from 35.4% to 38.3% in Spain during that same timeframe. The distance to the average decreased by half: from 5.6 points of GDP to 2.8 points. The projections for 2024 set down in the most recent draft budget confirm that the jump was not a one-off (38.6%).

The relatively faster growth in tax revenue than in nominal GDP in Spain may be attributable to several factors that can come in and out of play over time, with varying intensity. Specifically, we refer to the non-adjustment of the tax system for inflation, discretionary measures around taxes and contributions, the underestimation of GDP, growth in tax compliance, a reduction in the size of the shadow economy, and the decoupling between household income and GDP thanks to the above-mentioned income protection schemes. What do the studies tell us?

The work of García-Miralles and Martínez Pagés (2023) confirms that inflation has played a growing role, in tandem with the intensity of the bout of inflation that began in the second half of 2021 whose effects are concentrated in the personal income tax (Romero, 2024; Balladares and García-Miralles, 2024). Indeed, the net impact of the discretionary measures around rates, relief, and exemptions has been very small: during the period analysed, the governments have approved increases but also tax cuts, particularly to mitigate the impact of the crisis induced by the invasion of Ukraine. The authors conclude that over half of the increase in the ratio of revenue to GDP cannot be explained by the growth in prices, the economic recovery, or the tax measures approved. [3]

The decomposition of the change in the ratio of tax revenue-to-GDP provided by AIReF (2023) confirms this, albeit with certain caveats. AIReF finds that over half of the growth in the ratio of tax revenue-to-GDP is attributable to inflation (1.8 percentage points), concentrated in 2022 and that the discretionary measures reduced the ratio as a whole. This institution reduces the unexplained residual to one-quarter of the increase observed in the ratio (0.8 percentage points).

Lastly, De la Torre (2024) focuses on the residuals and attempts to quantify the existence and scale of improved VAT compliance. Adapting the EVADE methodology to take full advantage of the statistical sources for Spain, he suggests that the contraction of the shadow economy and increase in compliance explain an increase in VAT receipts of 6.2 billion euros between 2019 and 2022, which is equivalent to around 0.4 percentage points of GDP. He believes that the mainstreaming of electronic payments induced by the pandemic is the key to this process.

Conclusions

Analysis appears to support a triumphant reading of the tax revenue-to-GDP figures and the estimates regarding the size of the shadow economy in Spain. The shock induced by the pandemic led to growth in tax receipts without having to raise tax rates. The gap in the tax burden with respect to the EU-27 average in 2019 has closed by half, a gap which originated from a plethora of special tax treatments and a relatively larger shadow economy and level of tax fraud. As the first factor has not changed substantially, it has been deduced that resolution of the latter issues is responsible for reducing the gap.

However, this interpretation is overly simplistic. We know that the most important factor explaining the trend in tax revenue is the intense bout of inflation experienced between 2021 and 2023. The decision not to adjust legislation for inflation has implied a de facto increase in personal income tax rates. Secondly, very recent statistical adjustments to Spain’s GDP figures have affected the values that use GDP as their denominator. Further statistical revisions in the future cannot be totally ruled out. Thirdly, the sample of post-pandemic years is still small, and it remains to be seen which of the posited changes in economic agents’ conduct, such as reduced use of cash, will prove permanent. Fourth and last, despite the valuable and laudable efforts made, we still need better information about the size and dynamics of the shadow economy and tax fraud. We continue to await the creation of a permanent tax compliance analysis unit which, according to the White Book on Tax Reform, should come under the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IEF) (Committee of Experts, 2022).

In short, although there are signs that Spain has improved its relative position concerning its informal economy and tax fraud indicators in the last three years, we would urge caution pending confirmation of this interpretation via rigorous analyses and studies. Such an effort would additionally serve to provide us with the foundations for building a more ambitious strategy for placing Spain within the first quartile of the EU-27’s best-performing member states in terms of efforts to combat the shadow economy and tax evasion.

Notes

The author would like to thank Francisco de la Torre, Esteban García-Miralles, and Carlos Ocaña for their feedback on an earlier version of this paper.

Although the authors quantify the increase in the ratio between 2019 and 2022 at 3.7 percentage points, the subsequent statistical revisions to GDP and the definitive figure for 2023 (the authors work with the data available as of 3Q23 in their paper) explain the difference with the above-mentioned Eurostat figure (2.9 points).

References

AIReF. (2023). Technical Document on the Variability in Tax Revenues.

Technical Document, 5/2023.

www.airef.esBALLADARES, S. and GARCÍA-MIRALLES, E. (2024). Progresividad en frío: El impacto heterogéneo de la inflación sobre la recaudación por IRPF [Progressive taxation looked at objectively: The heterogeneous impact of inflation on personal income tax receipts].

Bank of Spain Occasional Papers, No. 2422.

www.bde.es CASE CENTER FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RESEARCH, PONIATOWSKI, G., BONCH-OSMOLOVSKIY, M., ŚMIETANKA, A. and SOJKA, A. (2023).

VAT gap in the EU. Report 2023. Executive Summary. Publications Office of the European Union.

https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2778/59019 COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS. (2022).

White Paper on Tax Reform. Institute of Fiscal Studies (IEF).

DE LA TORRE, F. (2024).

Did tax fraud and the shadow economy decline in the aftermath of the pandemic? Analysis 2019-23 based on VAT collection. EsadeEcPol.

www.esade.edu/ecpol/enELGIN, C., KOSE, M. A., OHNSORGE, F. and YU, S. (2021). Understanding Informality.

CERP Discussion Paper, 16497. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

GARCÍA-MIRALLES, E. and MARTÍNEZ PAGÉS, J. (2023). Government revenue in the wake of the pandemic. Tax residuals and inflation.

Economic Bulletin of the Bank of Spain. 2023/Q1 Article 16.

https://doi.org/10.53479/29732GOVERNMENT OF SPAIN. (2022).

Draft Budgetary Plan for 2023. Kingdom of Spain. 15 October 2022.

www.hacienda.gob.es GOVERNMENT OF SPAIN. (2023).

Stability Programme Update, 2023-2026. Kingdom of Spain. 28 April 2023.

www.hacienda.gob.es IEF. (2023). Opiniones y actitudes fiscales de los españoles en 2022 [Spaniards’ opinions and attitudes around tax, 2022].

Work Documents, 7/2023.

www.ief.esLAGO PEÑAS, S. (Dir.). (2018).

Economía sumergida y fraude fiscal en España: ¿qué sabemos? ¿qué podemos hacer? [Shadow economy and tax fraud in Spain: What do we know? What can we do?]. Funcas.

www.funcas.esPAPPADAÀ, F. and ROGOFF, K. (2023). Rethinking the Informal Economy and the Hugo Effect.

NBER Working Paper, 31963

www.nber.org/papers/w31963ROMERO, D. (2024). Crecimiento de la presión fiscal de los cuatro principales impuestos: papel estelar para el IRPF [Growth in tax burden implied by the four main taxes: Personal income tax steals the show]. Funcas Blog, 17 April 2024.

www.blog.funcas.esSCHNEIDER, F. (2022). New COVID-Related Results for Estimating the Shadow Economy in the Global Economy in 2021 and 2022.

International Economics and Economic Policy, 19, pp. 299–313.

SCHNEIDER, F. and ASLLANI, A. (2022). Taxation of the Informal Economy in the EU. European Parliament. November 2022.

www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/IPOL_STU(2022)734007

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics at Vigo University and Senior Researcher at Funcas