Spanish economic forecasts: 2024-2025

The Spanish economy is expected to grow by 2.5% in 2024 and another solid 1.8% next year, continuing to outpace the European average by a considerable margin. The favourable external competitiveness position is a key factor behind this performance; nonetheless, corporate and housing investment continue to lag pre-pandemic levels, undermining potential output, while the high structural public deficit increases vulnerability to geopolitical and financial risks.

Abstract: The Spanish economy continues to post healthy growth, outpacing the European average by a considerable margin. We are forecasting GDP growth of 2.5% this year and of 1.8% in 2025, buoyed by the external surplus, private sector deleveraging and, to a lesser degree, the NGEU funds. As a result, we are expecting the creation of 730,000 net new jobs over the next two years, which will nevertheless leave unemployment in the double digits. As for inflation, we are forecasting CPI of 3.3% in 2024, just 0.2pp below the 2023 figure. This inertia, which is typical of inflationary episodes, reflects the reversal of VAT and excise duty cuts on energy products (introduced in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine), wage agreements for restoring purchasing power and weak productivity trends. Disinflation should become more tangible in 2025, although we are still forecasting CPI above the ECB’s target of 2%, in both Spain and the rest of the Eurozone. Despite recent economic successes, corporate investment and investment in housing continue to lag pre-pandemic levels, undermining potential output. Lastly, the persistence of such a high structural public deficit leaves the Spanish economy vulnerable to geopolitical and financial risks.

Recent performance: Ongoing healthy momentum

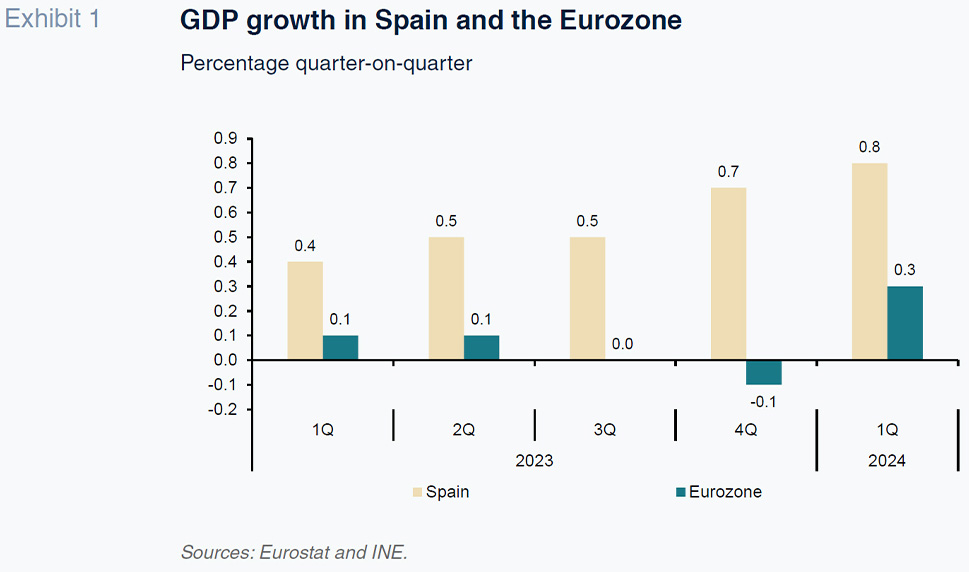

The revised national accounting statistics for the first quarter of 2024 raised the initially estimated quarter-on-quarter GDP figure by 0.1pp to 0.8%. The composition was largely unchanged from the provisional figures published in April, other than a smaller than initially estimated contraction in public spending. Of the total, 0.5pp of the first-quarter growth was the result of the contribution of the foreign sector, with net tourist and non-tourist service exports more than offsetting the contraction in goods exports. Domestic demand accounted for 0.3pp of the growth, underpinned by private consumption and investment.

As a result, the Spanish economy continued to report healthy growth in the first quarter, in contrast to far more moderate growth – and in some instances the odd quarter of contraction – we are seeing across the Eurozone (Exhibit 1).

Household gross disposable income continued to grow, at a sharp 8% year-on-year in the first quarter, albeit down from the rates observed during the last four quarters. The growth was driven by growth in employee compensation, social benefits (mainly pensions), albeit less of a force than in previous quarters, and property income, which jumped by 44% year-on-year, despite a sharp increase in interest payments. As a result, the savings rate in the first quarter of 2024 was the highest first-quarter figure in the history of the series, excluding the years of the pandemic (2020 and 2021), which were marked by anomalous excess savings. In seasonally adjusted terms, the savings rate rose to 14.2%, from 13% in 4Q23.

As for the second quarter, although not all of the information is in, the signals remain positive. Social Security contributors increased by 0.8% from from the growth observed in 1Q24, up from the 0.7% growth recorded in the previous quarter. The industrial activity indicators started the year largely where they left off last year, whereas the services activity indicators were less consistent: healthy overnight stays, air passenger and PMI readings compared to more lacklustre confidence and large enterprises sales reports. On the other hand, housing sales and mortgage activity are picking up. New business loans were also more dynamic in March and April. In short, the data available to date point to quarterly GDP growth of 0.6% in the second quarter.

Headline inflation has increased from a low of 2.8% in February to around 3.5% in recent months, shaped partly by step effects in energy products and as a result of the reversal of VAT rate cuts on electricity and gas. Core inflation, which paints a better picture of underlying inflationary pressures, has dropped from 3.6% at the start of the year to around 3% between April and June. Inflationary pressures remain strong in services, particularly all sectors related with tourism. In other words, the disinflation process is being curtailed by the trend in specific components, especially services, as well as step effects in energy products and the timeline for withdrawing the various anti-inflation measures.

The ECB, having raised its rate for the 10th consecutive time last September, cut its official rate by 25 basis points in June. Market rates, meanwhile, started to trend lower last autumn, pricing in swift easing by the ECB. In recent months, however, as those expectations have cooled, market rates have once again ticked higher. 12-month Euribor is moving up and down around the 3.6% mark. Elsewhere, the yield on Spanish bonds has been coming down since December, likewise with ups and downs, and is currently trading at around 3.2%. The sovereign risk premium dropped from over 100 basis points in 2023 to under 80 basis points in May, from where it has since risen due to the uncertainty generated in the Eurozone following the snap elections called in France.

The current account surplus hit a new record in the first quarter of 2024 of 11.9 billion euros. The goods trade deficit increased year-on-year, whereas the services trade surplus registered strong growth, fuelled by non-tourist services but especially by tourist service exports. As for the income deficit, net payments abroad increased slightly.

Budget outturn

Spain reported a deficit of 6.1 billion euros in the first quarter of 2024, compared to 3.5 billion euros in 1Q23, driven by higher deficits at the local and, above all, regional government levels. The deterioration in public finances is attributable to more moderate growth in revenue compared to expenses, with employee compensation standing out (1.9 billion euros higher than in 1Q23), along with interest expense (up 1.3 billion euros), particularly expenditure on pensions (which was some 2.3 billion euros higher than in the first quarter of 2023).

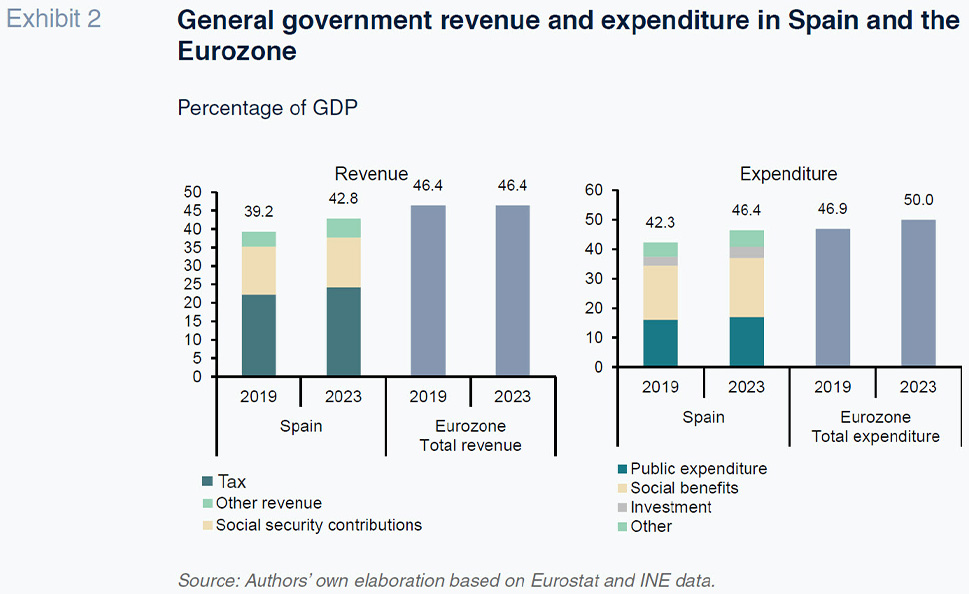

Total government receipts increased by 3.6 points as a percentage of GDP between 2019 and 2023, from 39.2% to 42.8% (Exhibit 2). Note, however, that around one percentage point of 2023 receipts came from transfers from Europe to fund the Recovery and Resilience Plan that had no equivalent in 2019. Looking only at tax and social contributions revenue, the percentage has increased from 35.2% of GDP to 37.7%. The bulk of that increase – 2.1 percentage points – has come from current taxes on personal and corporate income.

The growth in total public revenue contrasts with the stability observed in the European average over the same timeframe (in all instances expressed over GDP). Nevertheless, total receipts over GDP in Spain are still 3.6 percentage points below the European average (compared to a gap of 7.2pp in 2019).

Total expenditure, meanwhile, has increased by 4.1 percentage points of GDP, from 42.3% to 46.4%, albeit shaped by a similar distortion, as the 2023 figures include spending financed by European transfers that did not exist in 2019 (with no impact on the deficit). On a like-for-like basis, we estimate that government spending increased by 3.2 percentage points of GDP between 2019 and 2023. Of this increase, 1.4 points has gone to social transfers, mainly pensions. Among the remaining items, expenditure on intermediate goods has increased substantially (+0.6pp), as has gross capital formation (0.7pp), albeit largely attributable in this case to the Recovery and Resilience Plan.

A comparison with the pre-pandemic snapshot also signals a bigger increase in total public spending than that observed in the Eurozone. Despite that, the ratio of public expenditure over GDP is still below the European average, marked by a gap of 3.6 percentage points (one point down from 2019).

The short-term outlook is positive, but concerns over the public deficit and pace of investment linger

These forecasts assume less expansionary fiscal policy than in recent times, specifically the gradual unwinding of the anti-inflationary pressures, rollover of the last budget and reinstatement of the European fiscal rules, at a time when the debt burden needs to be financed in the market, as the ECB is rolling back its asset purchase programmes. In terms of monetary policy, we are now forecasting a more gradual rate-cutting path than previously. The ECB is going to have to factor the resilience of inflation and cautious attitude of the Federal Reserve, which is extremely important for the financial markets in general and the currency markets in particular, into its decisions. On the international front, while geopolitical uncertainties linger, the European economic situation is expected to gradually improve.

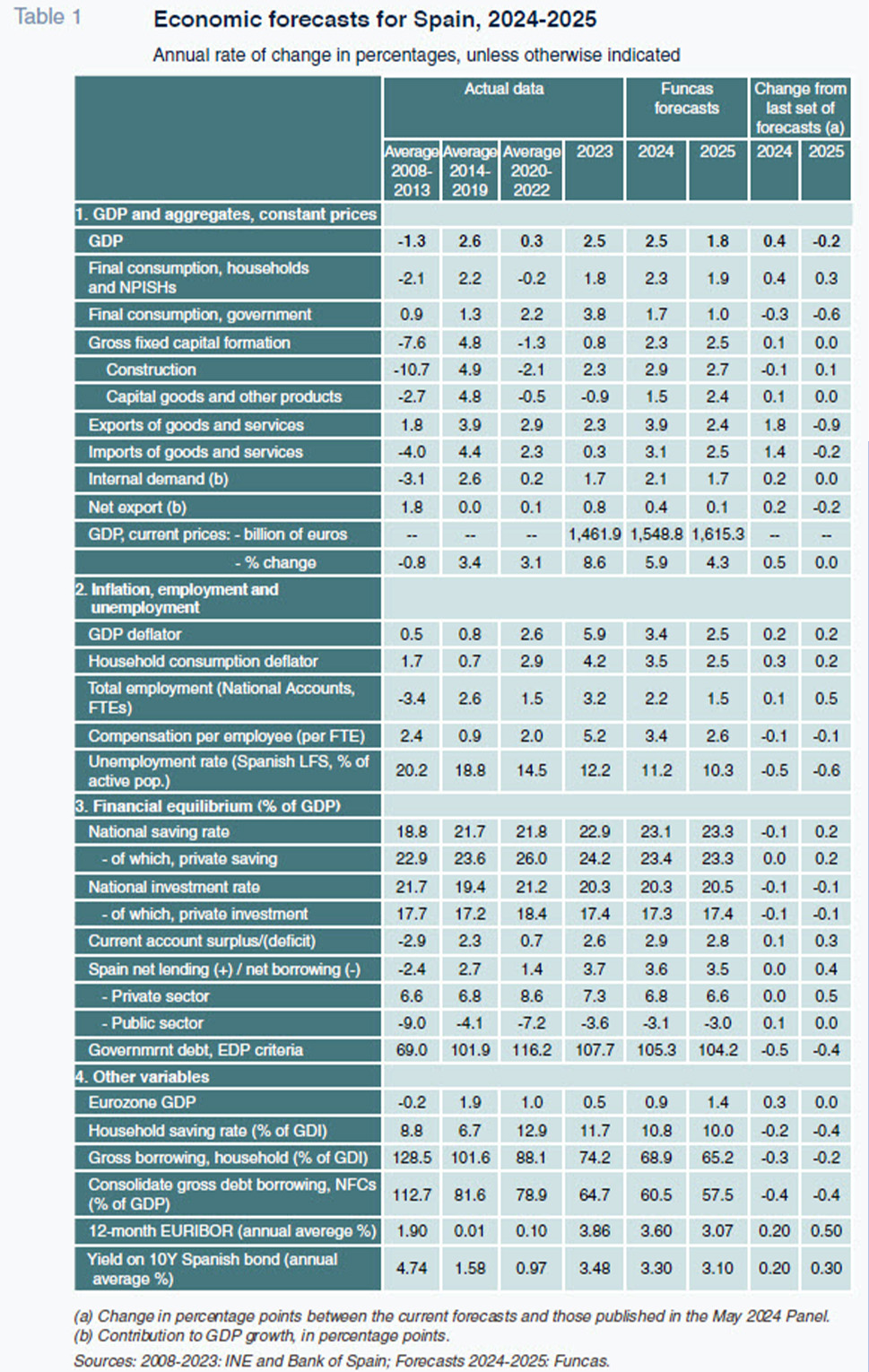

Framed by these assumptions, we are looking for healthy GDP growth throughout the projection period, consistently above the European average. In 2024, we are forecasting GDP growth of 2.5%, up 0.4pp from our last set of forecasts (Table 1). That upward revision partly reflects the inclusion of the first-quarter figure, which was better than expected. It also reflects a brighter outlook for private consumption, shaped by the existence of a higher stock of savings, according to the latest estimates (INE).

As a result, we are expecting internal demand to contribute 2.1 points of growth, which would be 0.4pp more than in 2023. That acceleration will be driven by private consumption (thanks to growth in household disposable income and the use of pent-up savings) and gross fixed capital formation. With respect to the latter, investment in infrastructure is expected to be the most dynamic component, with residential construction and investment in capital goods, both of which affected by interest rates and bottlenecks (in the case of the housing market), registering more moderate growth. Public spending is the only component of internal demand expected to drag on growth, in line with the assumptions outlined above.

Despite a lethargic European economy, the main destination for Spanish goods exports, foreign demand is expected to continue to contribute positively to growth. Non-tourist service exports and, more so, tourist service exports should fare better, thanks to the favourable competitive positioning of Spanish companies in these sectors and reduced reliance on the ailing European industrial sector. Imports are expected to recover in line with long-run elasticities (in 2022-2023, global supply chain disruptions and the energy crisis led to an anomalous trend in imports, which is not expected to be repeated during the projection horizon). As a result, we expect the foreign sector to contribute 0.4 points to growth this year, which is half of the 2023 contribution but nevertheless a solid performance.

In 2025, the economy is expected to grow by 1.8%, slowing from this year. The slowdown is expected to come from internal and external demand. On the domestic front, consumption is likely to ease: depletion of the savings buffer will weigh on household spending, as will the scant margin for growth in public spending in light of the need to comply with the reinstated European fiscal rules. Investment should accelerate somewhat thanks to a spurt of investment as the final amounts of NGEU funds are allocated. This effect will not, however, offset the slowdown in consumption, so that we expect internal demand to contribute 1.7 points to growth, down 0.4pp from 2024.

Meanwhile we expect external demand to contribute 0.1pp to growth, down 0.3pp from this year, as the boom in tourism runs its course, in light of the saturation levels already becoming apparent. Goods exports could recover somewhat, in line with gradual economic recovery in Europe, while non-tourist service exports should remain dynamic, albeit not enough to make up for the slump in tourist exports. More normal import elasticities will also weigh on this contribution.

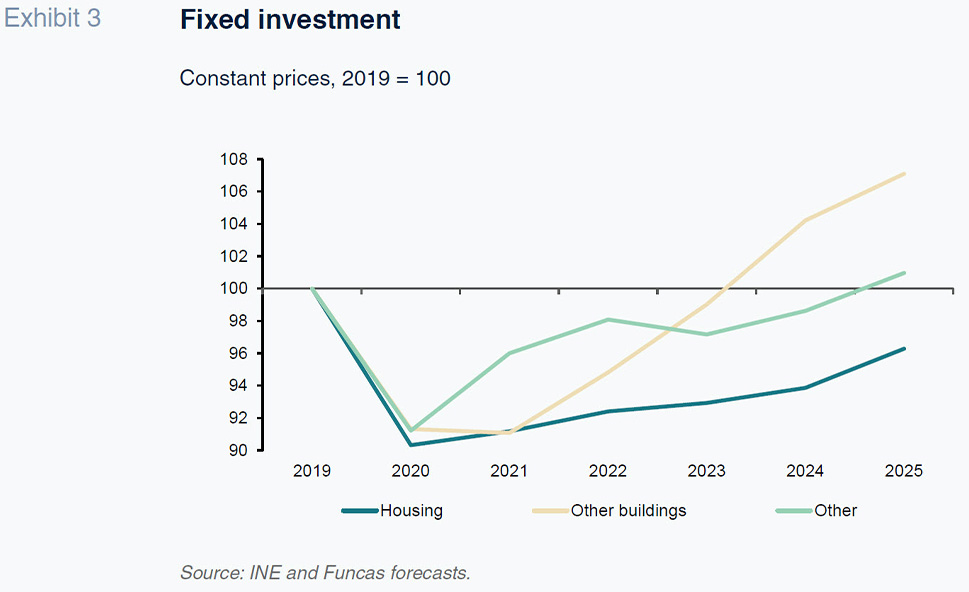

In a nutshell, we are forecasting sustained growth in the next two years. Beyond 2025, the outlook depends on investment, which is key to boosting productivity and potential output. Here, there are some concerns (Exhibit 3). Firstly, the anticipated uptick in investment in housing will not be sufficient to mitigate, or not aggravate, the shortage of housing. Therefore, in the absence of reforms, the housing market is likely to remain tight, weighing on mobility and the labour force. Secondly, according to our forecasts, investment in productive assets is not expected to revisit pre-pandemic levels until 2025. This variable is the key remaining laggard.

Even assuming energy market stabilisation and the absence of a new supply shock, inflation is hardly expected to improve this year. We are forecasting CPI of 3.3% in 2024, just 0.2pp below the 2023 figure. This inertia, which is typical of inflationary episodes, reflects the reversal of VAT and excise duty cuts on energy products (introduced in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine), the agreements for restoring purchasing power and weak productivity trends. Disinflation should become more tangible in 2025, although we are still forecasting CPI above the ECB’s target of 2%, in Spain and in the rest of the Eurozone. The GDP deflator, which is a better proxy for the underlying trends, is expected to trend in line with CPI, evidencing stability in the relative terms of trade.

Employment should remain a driving force: we are forecasting net job creation of 730,000 between 2024 and 2025. However, job creation is likely to lose momentum in 2025 as the economy slows and the labour force shrinks (with net inflows of foreign workers expected to slow in the wake of the post-pandemic surge). Unemployment is expected to average 10.3% in 2025, one of the highest rates in Europe.

Spain’s external accounts are expected to continue to improve thanks to the positive contribution to growth by the external sector and also stabilisation in the relative terms of trade (stable real rate of exchange). We are forecasting a considerable current account surplus of just under 3% of GDP.

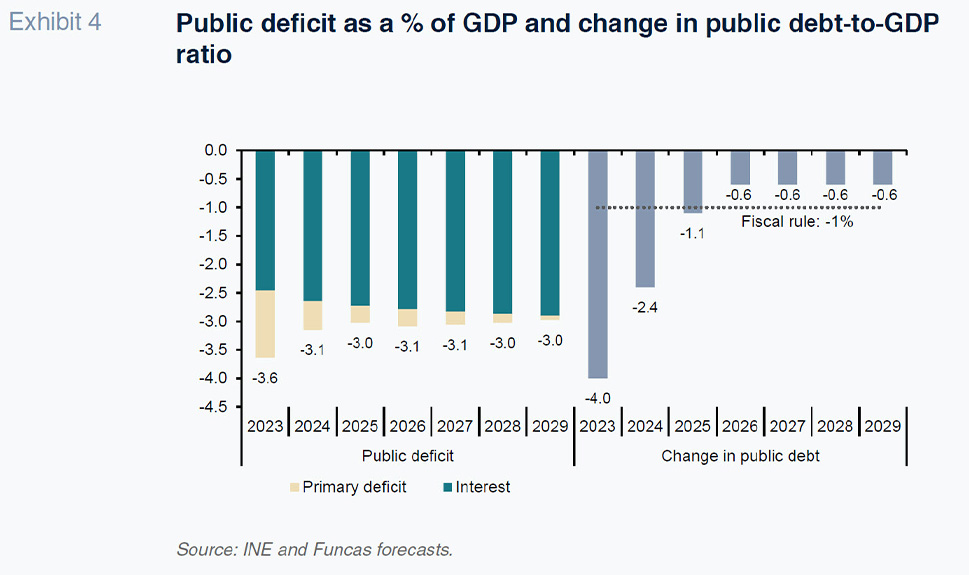

We expect both the deficit and public debt to fall as a percentage of GDP, due mainly to circumstantial factors. This year, the fiscal indicators will move within the thresholds stipulated under the reinstated rules. In 2025, however, we expect the deficit to stagnate at around 3%. As a result, assuming no policy changes, potential output of around 1.75% per annum and inflation of 2%, the ratio of debt-to-GDP will fail to come down at the rate required to comply with the fiscal rules (Exhibit 4). To do so, the deficit would have to be cut further and economic growth would need to be somewhat higher, an outcome that will only be possible in a scenario of investment recovery plus reforms. In theory, inflation of over 2% would also help erode the real value of Spain’s debt but that assumption is inconsistent with the ECB’s target.

Risks

The main risk to delivery of these forecasts continues to lie with geopolitical strains, particularly the potential for intensification of the crises in Ukraine and the Middle East. There is also a chance of renewed stress in the financial markets, as we saw recently when Macron called a snap election in France. Spain’s public debt and deficit levels leave it vulnerable to these eventualities.

Other than those risks, we do not see threats to Spain’s current growth trajectory: besides its fiscal shortcomings, there are no macroeconomic imbalances or bubbles in any area of the economy; the balance of payments surplus is solid, and Spain’s households and businesses have improved their financial situation on the whole. In the short-term we see more upside than downside. Medium-term, the scenario is more uncertain.

The current savings buffer and financial health of Spanish households implies room for higher growth in consumption than we are currently forecasting. The significant shortage of housing could fuel stronger than forecast activity in the construction sector. Lastly, our forecasts for tourism, where growth has been topping our expectations consistently in recent years, are conservative.

Longer-term, however, the trend in GDP per capita remains a concern, as a result of meagre growth in productivity, the Spanish economy’s Achilles heel. Against that backdrop, the stagnation in corporate investment is of particular concern. In the short-term, this factor does not imply a risk of inducing a recession but in the absence of a significant recovery, it will exacerbate the productivity problem and drag on the Spanish economy’s potential output in the years to come. Finally, the weakness in residential investment, were it to persist, could constrain labour mobility and the inflow of foreign workers and similarly weigh on potential output.

Raymond Torres, María Jesús Fernández and Fernando Gómez Díaz. Funcas