TLTRO and bank liquidity in the new rate scenario

The ECB´s targeted longer-term refinancing operations, or TLTROs, were designed to be one of the key mechanisms to keep credit flowing through the banking system to the real economy during the crisis. Beyond the negative impact on banks´ earnings of recent changes to TLTRO terms in order to better align them with other monetary policy instruments, the European and Spanish banking systems have sufficient liquidity to handle the maturity or prepayment of their TLTRO funds, as well as to meet anticipated credit growth next year, thanks to their excess reserves, evolution of retail deposits and funds, and planned bond market issuance.

Abstract: The European Central Bank’s special liquidity facilities known as targeted longer-term refinancing operations, or TLTROs, were designed to be one of the key mechanisms for monetary policy transmission via the banking system by providing the latter with a source of stable long-term funding on highly favourable terms, essential to keeping credit flowing. Although the purpose of those rounds of financing was to boost the provision of credit to the real economy, the truth is lending barely grew, primarily due to scant demand in the context of deep macroeconomic uncertainty, firstly due to ensuing pandemic developments and later due to the energy crisis aggravated by the invasion of Ukraine. The advantageous TLTRO terms intrinsic in the design of these instruments now clash, however, with the new monetary policy objectives implemented by the ECB to halt inflation: rapid rate hikes and liquidity absorption via the withdrawal of its unconventional asset purchase programmes. The TLTROs, as currently configured as regards cost and terms, constitute somewhat of an anomaly in the prevailing context of monetary tightening, which is why the ECB, at its last Governing Council meeting, changed the terms applicable to the various rounds of TLTROs in order to better align them with those of other key monetary policy instruments. Beyond the negative impact on their earnings of the elimination of that source of liquidity and the associated carry trade, foreseeably offset by the favourable effect of the rate increases on their net interest margins, the European and Spanish banking systems have sufficient liquidity to handle the maturity or, if they so decide, prepayment of their TLTRO funds thanks to their excess reserves. Meanwhile, growth in retail deposits and funds and bond market issuance is expected to be sufficient to cover the anticipated growth in credit next year.

The role of the TLTROs in response to the pandemic

Although it had already created earlier series of TLTROs, the latter played a particularly predominant role in the toolkit deployed by the European Central Bank (ECB) in response to the pandemic with a view to keeping credit flowing to the real economy. Specifically, in June 2020 the ECB reformulated those lending operations to provide the banking sector with particularly attractive terms and conditions. Firstly, it provided longer-term refinancing operations with maturities of up to three years; and secondly it provided them at an especially low cost. More specifically, it articulated periods with special terms in which the cost of the loans was calculated as the average deposit facility rate (which stood at -0.5% at the time), less 50 basis points, so long as the borrowing banks met their lending thresholds throughout. Those special rate periods ran from June 2020 to June 2022.

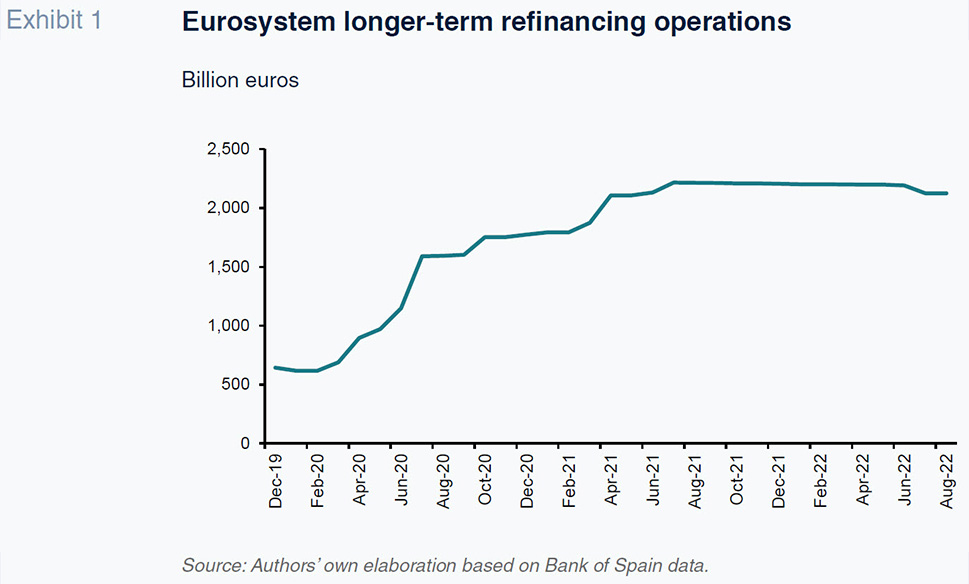

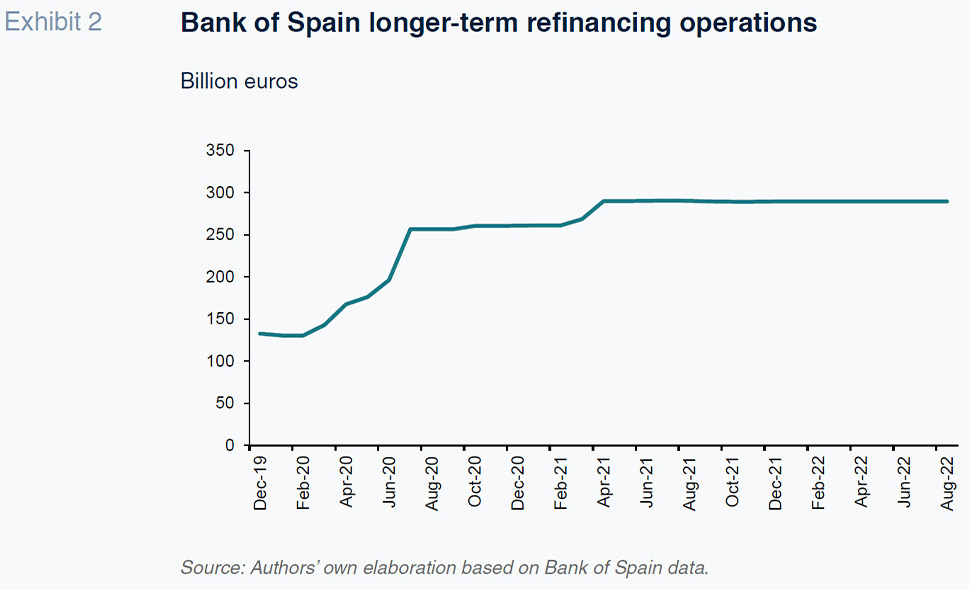

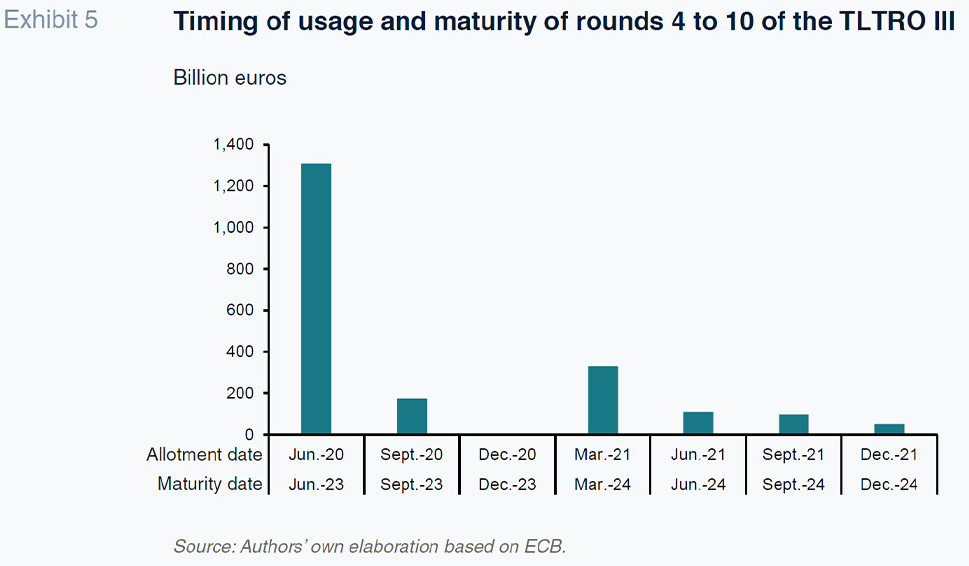

Those attractive rates led to very intensive usage of the facility, particularly between June 2020 and June 2021, as shown in Exhibits 1 and 2. As a result, the European banking system as a whole has drawn down approximately 2.1 trillion euros under the TLTROs, with roughly 14% (290 billion euros) in the hands of the Spanish banks.

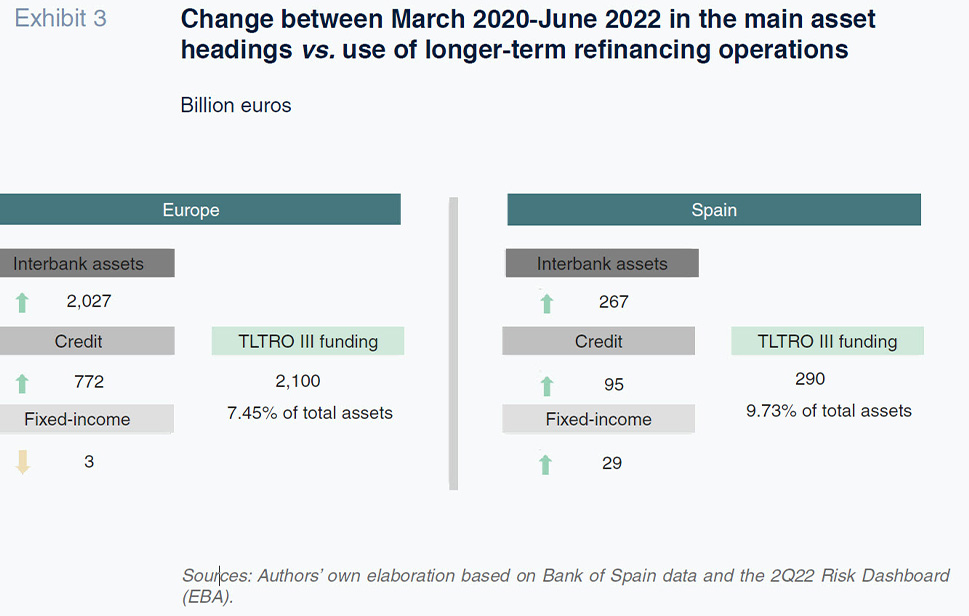

Although the purpose of those rounds of financing was to boost the provision of credit to the real economy, the truth is lending barely grew, primarily due to scant demand in the context of deep macroeconomic uncertainty, firstly due to ensuing pandemic developments and later due to the energy crisis aggravated by the invasion of Ukraine. That is why the large majority of the financing obtained via the TLTROs has remained within the banks’ assets as liquidity deposited at the central bank. Specifically, as shown in Exhibit 3, compared to TLTRO usage of around 2.1 trillion euros at the European level (approximately 7.5% of total assets), the stock of credit increased a meagre 772 billion euros between March 2020 and June 2022, while the increase in liquidity (interbank assets, or “due from banks”) during the same period was close to 2 trillion euros.

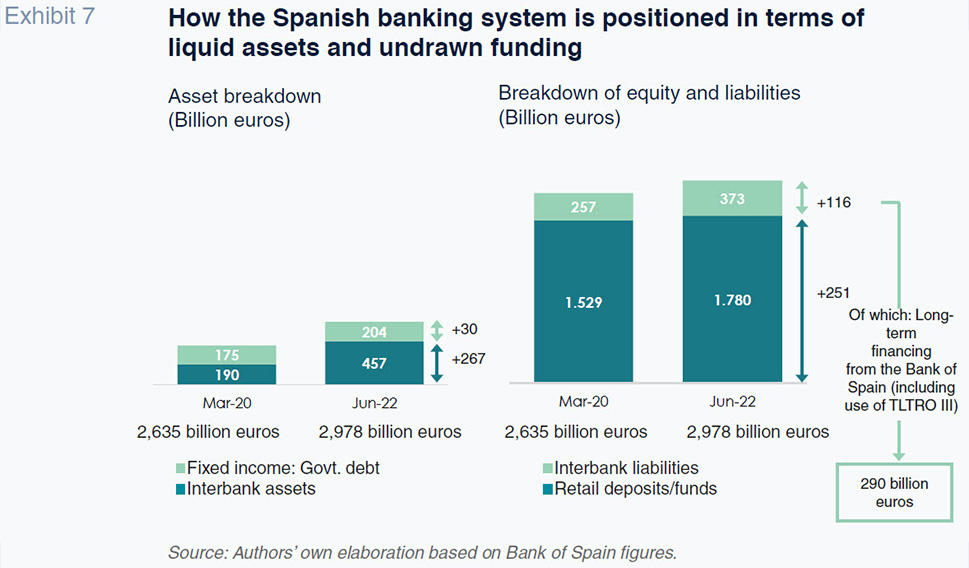

The dynamics in Spain have been very similar. In fact, the growth in credit has been even smaller, increasing just 95 billion euros compared to usage of the TLTRO III of 290 billion euros, most of which has been kept liquid (“due from banks”: +270 billion euros), with a portion also invested in fixed-income securities (+29 billion euros), mainly sovereign bonds.

Alignment between TLTROs and the ECB’s new anti-inflationary monetary policy

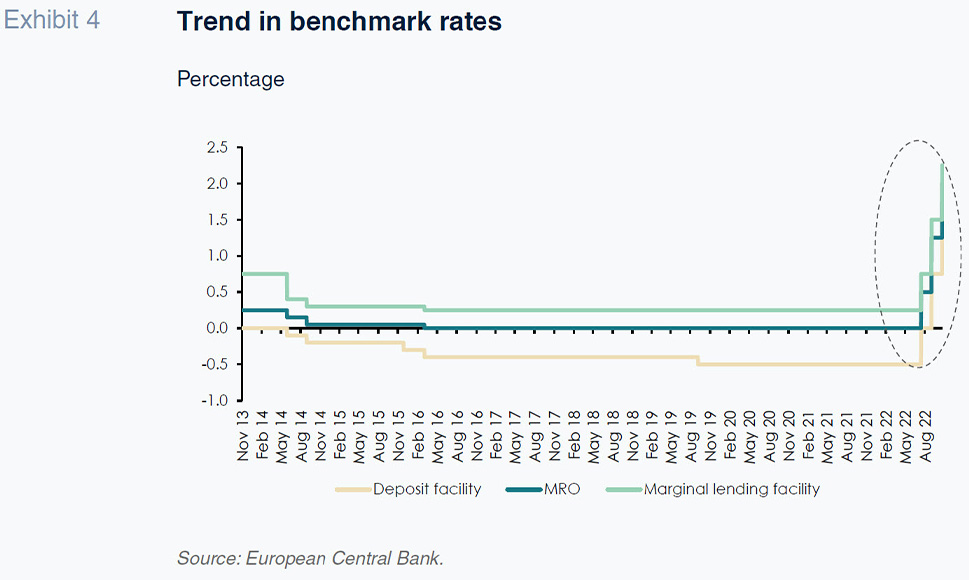

The macroeconomic scenario that gave rise to the rollout of these measures has been turned on its head by the current inflationary pressures not seen for more than four decades. Consequently, the ECB, framed by its firm commitment to controlling inflation, has been gradually tightening its monetary policy, putting an end to the purchase of assets under its pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) and its ordinary asset purchase programme (APP) between March and June of this year. In addition, it has been increasing its benchmark rates, three times so far, by 200 basis points in total, a process which is likely set to continue.

Under the new monetary policy approach, it no longer made sense to keep the system so awash with liquidity as a result of its intense usage of the TLTROs. The banks had no incentive to repay them as the method for calculating the cost of that funding, while appropriate given the climate of ultra-low rates and need to stimulate lending, created perverse incentives in the scenario of very rapid rate increases underway since the start of the summer.

As a result, after its last Governing Council Meeting, the ECB introduced changes to the method for calculating the cost of the TLTRO III. Note that the changes will not apply retroactively so as to avoid any potential legal issues with the banks but will take effect from November 2022 until the operations mature.

The banks that availed of that source of ECB funding since June 2020 and met their lending targets have been able to benefit from a funding cost of -1% during the special rate periods (from June 2020 to June 2022). Under the new regime, from June 2022 onward two additional calculation periods will apply in which, in contrast to the outgoing calculation regime (where the applicable rate was the average deposit rate during the entire term of the operation), the following methods will be used:

- Between June 24th, 2022, and November 22nd, 2022, the applicable rate will be the average deposit facility rate between the start of the operation and November 22nd.

- From November 22nd until maturity of the operation, or its prepayment, as the case may be, the applicable rate will the the average deposit facility rate during that period.

The new regime applicable from November 2022 eliminates the significant carry that was being earned by depositing outstanding TLTRO funds with the deposit facility as a result of their (negative) funding cost, as the benchmark deposit facility rate was in negative territory for over two years.

Elimination of that gap will have a significant impact on the banking sector’s earnings in 2023 as the carry will disappear. It is estimated that the Spanish banks generated approximately 1.4 billion euros of income between January and November 2022 by funding at a negative rate under the TLTRO (-0.67%) and investing the proceeds in the deposit facility (-0.11% on average during the period).

By way of example, if the outgoing calculation method had been left in place, that estimated return of 1.4 billion euros in 2022 would have been more than twice as high in 2023, in the likely event that the deposit facility rate trends towards the 3% mark by the middle of next year.

Leaving that regime in place would have unquestionably given the banks a clear incentive to keep those funds on their balance sheets. That arbitrage trade has been eliminated by the decision to equate the cost of that funding with the return on the deposit facility. The ECB has created new voluntary repayment windows, without penalising any banks that want to keep that funding to maturity.

Bank liquidity  vis-à-vis TLTRO maturities

vis-à-vis TLTRO maturities

Aside from the possibility that the banks could decide to prepay their TLTRO funds by taking advantage of the new windows, it is worth noting that nearly 60% of the 2.1 trillion euros of funding outstanding falls due next June, as the bulk of the operations were concentrated in the second half of 2020.

Given that the banks have three more prepayment windows than initially contemplated, the first in November, which is when the new calculation method starts to apply, and another two during the first quarter of next year, it is unlikely there will be a ‘cliff edge’ effect in TLTRO repayments insofar as the banks are free to decide when to repay but will not be penalised by the new funding cost in the event they prefer to hold on to that liquidity to maturity.

Although a dramatic cliff edge effect is not likely, the gradual absorption of most of this source of the banks’ liquidity warrants an assessment of the European and Spanish bank systems’ ability to handle the situation.

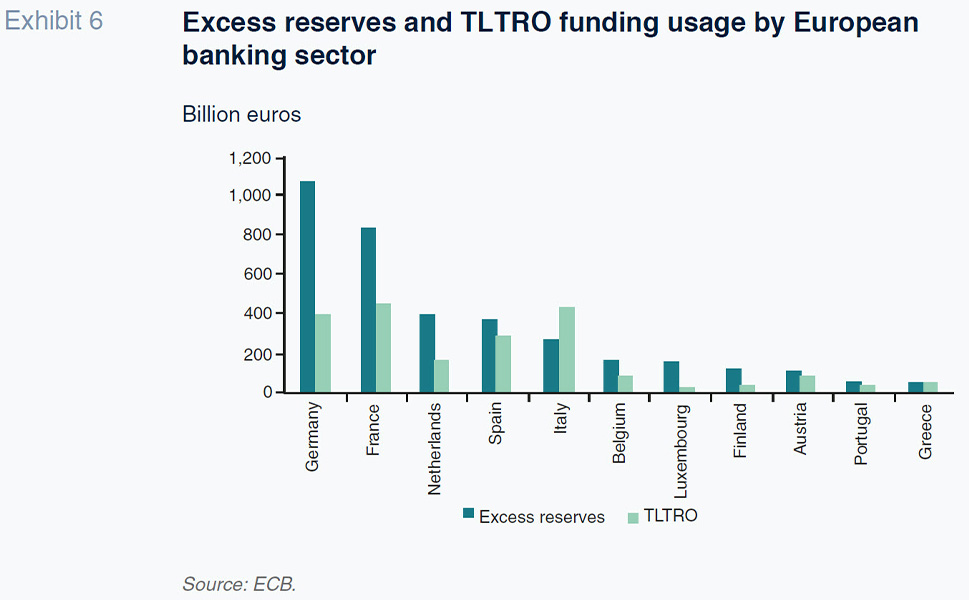

As shown in Exhibit 6, analysing the matter from a static repayment capacity perspective, we see that the main European banking systems, except for the Italian system, hold more excess reserves than TLTRO funds. It is fair to say, therefore, that even if the European banks accelerate repayment of their TLTRO funding, they have enough liquid assets to handle the situation without provoking balance sheet mismatches.

Specifically in Spain, as shown in Exhibit 7, the volume of liquid assets on deposit by the banks with the central bank stands at around 460 billion euros, which is more than enough to cover their long-term funding maturities (290 billion euros). In addition to their interbank assets, the banks have a buffer of government debt securities that mature in less than one year, which is when the bulk of their TLTRO III funding falls due.

Aside from the banking system’s ability to repay their TLTRO funds, it is worth highlighting the banks’ ability to cater to the forecast growth in credit from a dynamic balance sheet standpoint without triggering imbalances in the retail or wholesale funding markets.

With the economy expected to slow sharply in 2023, it is likely that growth in credit will be very small, and at any rate lower than foreseeable growth in customer deposits and funds. Between that positive liquidity gap in the retail segment, coupled with the bond market issuance contemplated by the main sector players, as evidenced in the EBA’s most recently published Funding Plan, there would appear to be sufficient slack to absorb the rollback of the TLTROs without sparking liquidity tensions and without having to be overly aggressive in looking for retail deposits.

Conclusions

Framed by the ECB’s efforts to stem the rise in inflation by raising rates and mopping up liquidity, the time has also come to reformulate the TLTROs in order to eliminate the arbitrage opportunity that had opened up, specifically by encouraging the banks to repay those funds without penalising those who wish to hold them to maturity.

Beyond the negative impact on their earnings of the elimination of that source of liquidity and the associated carry trade, foreseeably offset by the favourable effect of the rate increases on their net interest margins, the European and Spanish banking systems have sufficient liquidity to handle the maturity or, if they so decide, prepayment of their TLTRO funds thanks to their excess reserves, while growth in retail deposits and funds and bond market issuance is expected to be sufficient to cover the anticipated growth in credit next year.

References

EBA. (2022). Risk Dashboard for the second quarter of 2022.

Marta Alberni, Ángel Berges and María Rodríguez. Afi