Rising interest rates: Initial effects on credit

Rising interest rates are rapidly translating into a considerable increase in borrowing costs, putting a strain on households and companies, which had grown accustomed to exceptionally lax financial conditions. In parallel, the increase in rates is already materializing in the form of some retrenchment in lending in Spain, particularly in the mortgage segment.

Abstract: Rising interest rates are translating into a considerable increase in borrowing costs over a short period of time. Households and companies will face difficulties in tackling this situation not only because of tighter financing conditions, but also because they come in the wake of a very long period of exceptional financial and inflationary circumstances. As of last August, the average rates being charged in Spain were still below the European average in 12-month consumer loans (4.16%) but were higher (7.39%) in longer-dated paper (up to 5 years). In the mortgage segment, the average rate being charged is among the lowest in the eurozone, France being the only one of the larger European economies to charge less (1.58%). In the first eight months of the year, average mortgage rates climbed 0.59 percentage points higher. As for business lending, the rates trend is less consistent. In the wake of notable growth in 2020 (6.3% year-on-year), fuelled by the support and public guarantee schemes rolled out during the pandemic, growth in lending has slowed significantly and has become more volatile, contracting, for example, by 0.2% in June only to register growth of 2% in August. On the whole, in Spain, lending has slowed in the wake of the efforts made to keep credit flowing to the private sector during the pandemic, mostly targeting the business segment. Specifically, the increase in interest rates is already materialising in a degree of retrenchment in lending activity, particularly in the mortgage segment.

Credit, monetary policy transmission channels and financial situation

After over a decade of ultra-low or negative rates, economic agents currently face a swift increase in rates, which can be viewed as a process of normalisation after years of extraordinary circumstances, induced primarily by the central banks on either side of the Atlantic in an attempt to stem the rapid rise in inflation. The credit markets are a fundamental part of the process insofar as they constitute one of the main channels of monetary policy transmission. However, many households and companies will face difficulties in tackling this situation not only because of tighter financing conditions, but also because they come in the wake of a very long period of exceptional financial and inflationary circumstances. Note additionally that the idea is not to “cool” the credit markets in response to a boom or biases that could lead to a bubble in certain markets, such as the property market, as was the case during the financial crisis. Instead the idea is to slow the financing that fuels consumption and investment, so curbing some of the run-up in prices. Some inflation, however, mainly that induced by the surge in energy costs, is harder for the central banks to address.

That tricky situation has prompted the central banks to use interest rate policy to shape investment and consumption through the channel that is one of the most difficult to pin down yet among the most powerful in terms of its ramifications: expectations. As suggested by the ECB’s Chief Economist, Philip Lane, in a public speech

[1] given on October 11

th, 2022, reducing inflation is a complicated process that requires a grasp of several links: (i) the link between monetary policy instruments (including interest rates) and financial conditions; (ii) the link between financial conditions and economic slack; and (iii) the link between economic slack and inflation pressures. As Lane points out, “if inflation expectations are broadly anchored, monetary policy is that needed to ensure expectations remain anchored; but if inflation expectations are de-anchored (or at serious risk of being de-anchored), monetary policy needs to ensure inflation expectations are re-anchored.” He also acknowledged that the fact that rates had been so low for so long could cause asymmetric spillovers in financial markets no longer used to policy shifts.

The situation is not straightforward in the eurozone, nor other jurisdictions. In October, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published its Global Financial Stability Report in which it suggested that interest rates and risk asset prices have been extremely volatile in recent months. In the wake of the rate increases by the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank, among other central banks, riskier investments and emerging market sovereign bonds have notched up significant losses, while other investments, such as crypto assets, have likewise sustained losses, as well as extreme volatility.

With respect to the credit markets, the IMF noted in its report that “as central banks aggressively tighten monetary policy, soaring borrowing costs and tighter lending standards, coupled with stretched valuations after years of rising prices, could adversely affect housing markets. In a worst-case scenario, real house price declines could be significant.”

Be that as it may, it is important to differentiate between financial conditions in different geographies. In the eurozone, the banks are much better capitalised and more financially stable than they were in 2008. Moreover, although the credit markets have been recovering, that momentum was nowhere near what could be termed a boom. At any rate, as indicated in this paper, there are some significant differences in the trend in credit in the eurozone in the face of rising interest rates that are worth singling out.

Credit and interest rates in the eurozone

Both official and interbank rates have increased sharply in the eurozone this year. On October 27th, 2022, the ECB decided to raise its official rate by a further 75 basis points. The European monetary authority noted that “with this third major policy rate increase in a row, the Governing Council has made substantial progress in withdrawing monetary policy accommodation”, adding that it, “expects to raise interest rates further, to ensure the timely return of inflation to its 2% medium-term inflation target.”

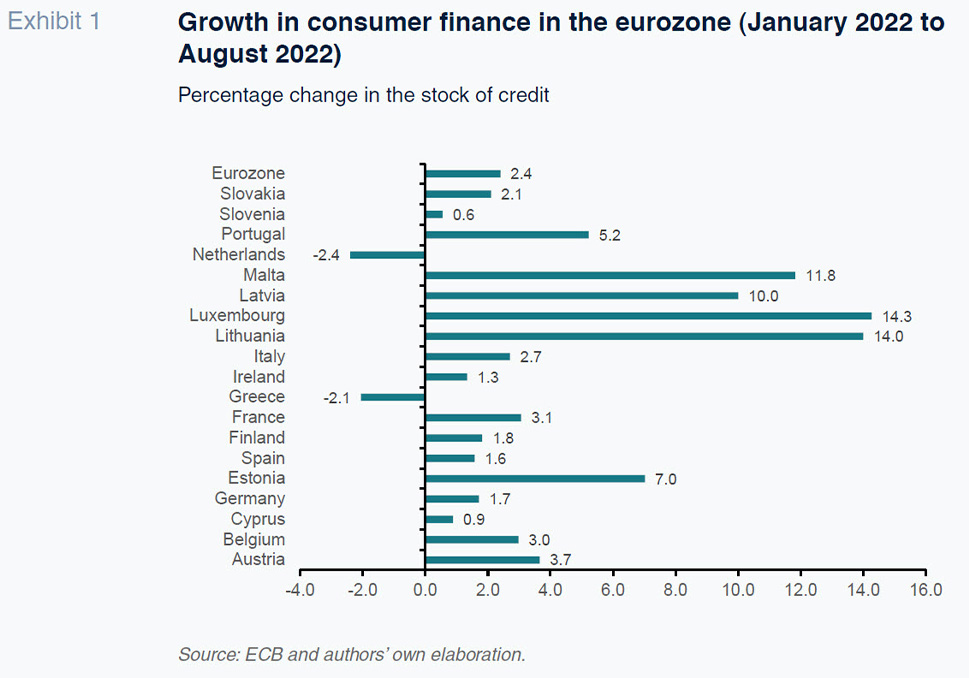

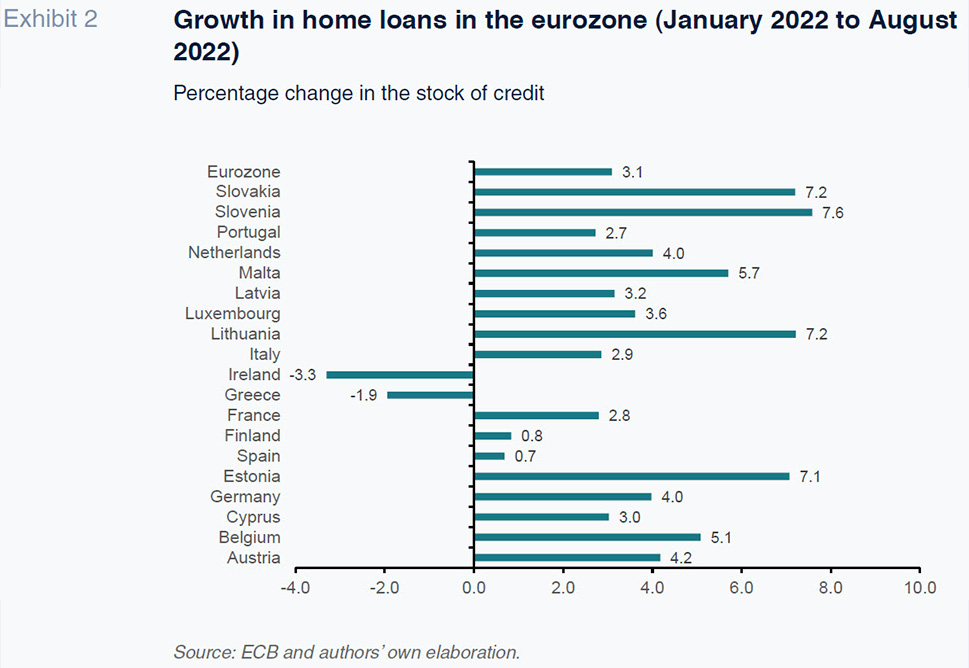

12-month EURIBOR, meanwhile, was closing in on the 3% mark and still rising as of the end of October, implying a significant increase in borrowing costs considering the fact that EURIBOR stood at -0.5% at the start of this year. One of the quickest manifestations of the higher interest rates is the trend in growth in consumer finance. As shown in Exhibit 1, between the start of 2022 and August (latest reading available), consumer finance registered accumulated growth of 2.4% in the eurozone. The growth during those eight months was uneven, however. While Malta, Luxembourg, Latvia and Lithuania registered double-digit growth, consumer finance contracted by around 2% in Netherlands and Greece. In Spain, where consumer finance had been experiencing strong momentum, growth eased to 1.6% in 8M22, which is very similar to the rate reported by Germany (1.7%), while other major economies, including Italy (2.7%) and France (3.1%), registered above average growth. However, on account of its magnitude and importance to household planning and budgeting, most of our analysis is focused on determining how the increase in rates in 2022 is affecting mortgage lending. The ECB data indicate that between January and August of this year, home financing in the eurozone registered growth of 3.1% (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2 likewise reveals a wide range of percentage changes in the stock of home loans. In Slovakia, Slovenia, Lithuania and Estonia, growth in that segment topped 7% in 8M22. The stock of home loans contracted in contrast in Ireland (-3.3%) and Greece (-1.9%). In Spain, growth in home loans was moderate (0.7%) by comparison with that registered in Germany (4%), Italy (2.9%) and France (2.8%).

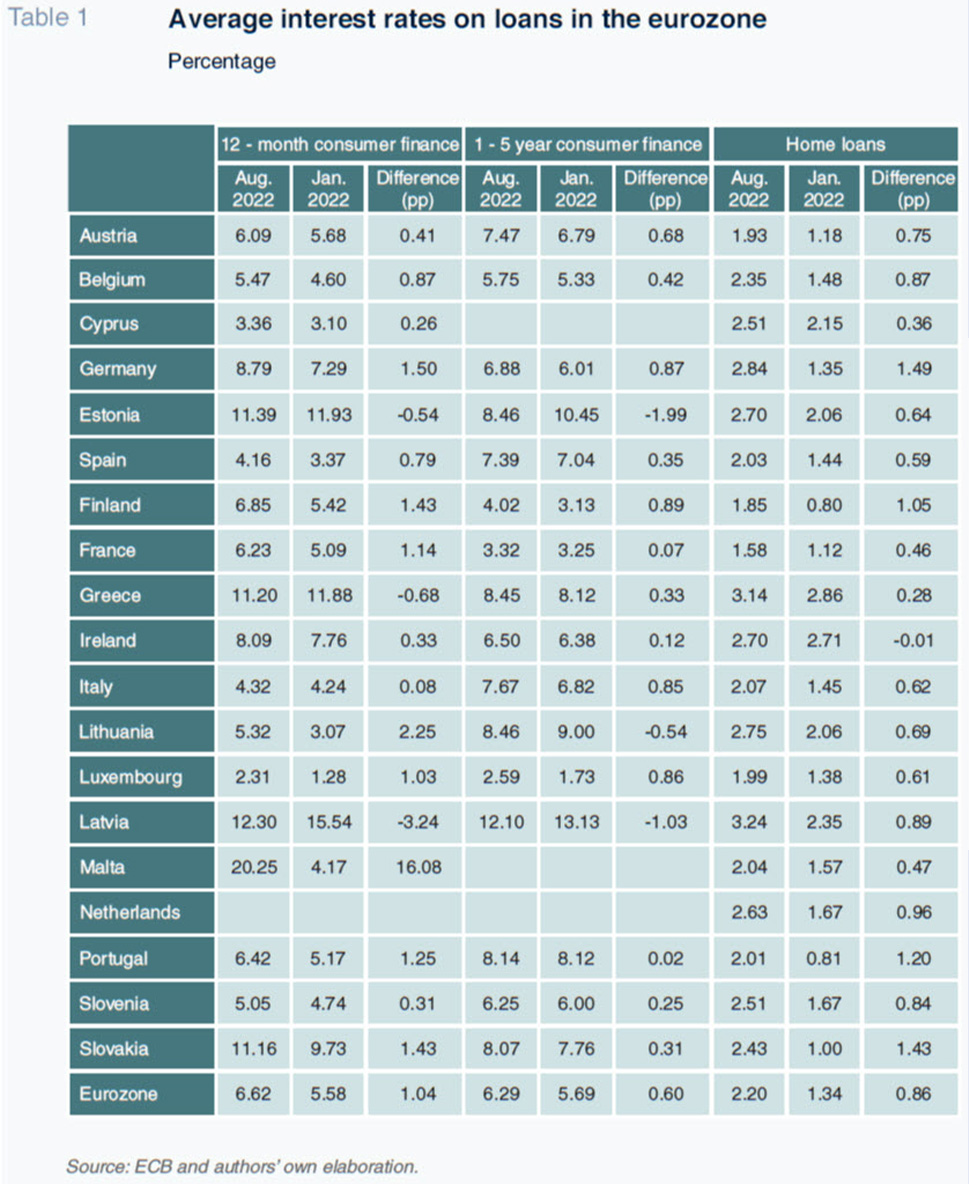

Despite the existence of a single financial market in the EU, financial conditions are not uniform for several reasons. The information tracked by the European Central Bank provides insight into the differences in borrowing rates. The average rate of interest charged for a 12-month consumer loan has increased by 1.04pp from 5.58% in January to 6.62% in August. In longer-dated consumer loans – up to 5 years – the average rate has climbed 0.6pp higher to 6.29%. In the mortgage segment, lastly, the average rate stood at 2.2% as of August, which is up 0.86pp from January. As of last August, the average rates being charged in Spain were still below the European average in 12-month consumer loans (4.16%) but were higher (7.39%) in longer-dated paper (up to 5 years). In the mortgage segment, the average rate being charged is among the lowest in the eurozone, France being the only one of the larger economies to charge less (1.58%). In the first eight months of the year, that average rate climbed 0.59 percentage points higher.

State of play in banking and borrowing terms in Spain

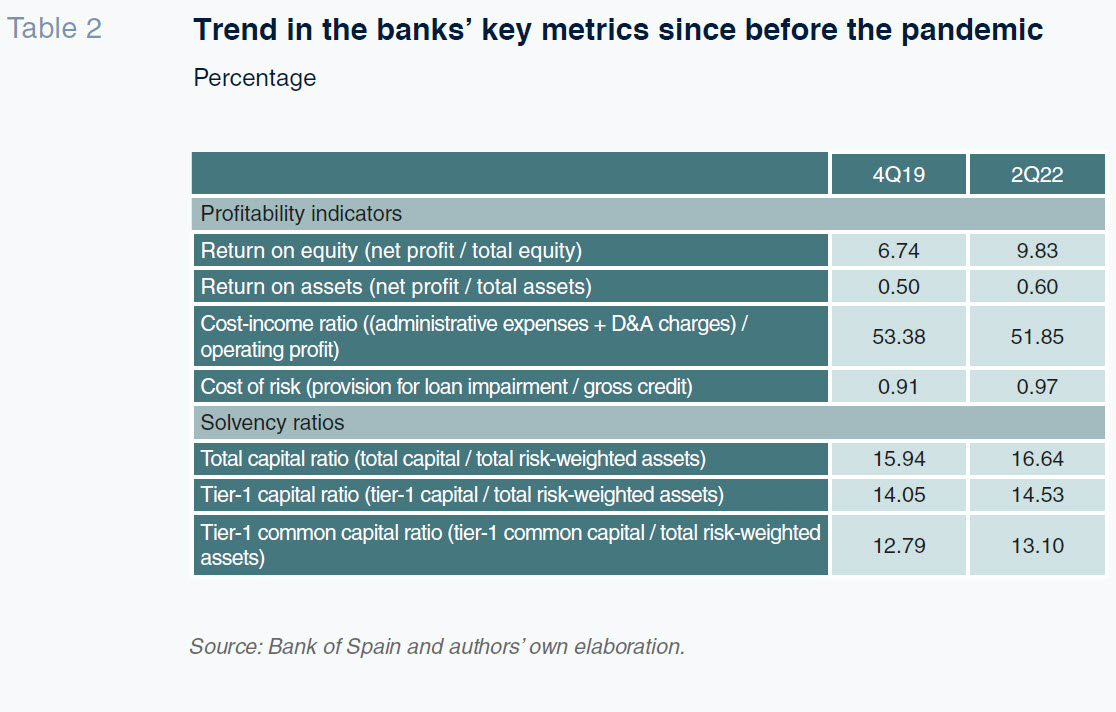

Borrowing terms depend on supply and demand. Demand remains somewhat subdued in the wake of the post-pandemic rebound, shaped by the new sources of economic uncertainty arising from the geopolitical turmoil and inflation. Supply is in a better place than right before the pandemic but there are risks – mainly due to the link between economic uncertainty, the banking business and non-performance – that warrant caution. Nevertheless, the recent indicators published by the Bank of Spain, gleaned from the separate financial statements of the banks it oversees, reveal an increase in the system’s return on equity from 6.74% in the last quarter of 2019 to 9.83% as of the second quarter of 2022. The return on their assets has widened (from 0.50% to 0.60%), albeit still at low levels. The cost-income ratio has also improved, from 53.38% to 51.85%. Meanwhile, the Spanish banks continue to replenish capital, nudged in that direction by regulatory and market pressures, with tier-1 capital at 13.10% of risk-weighted assets.

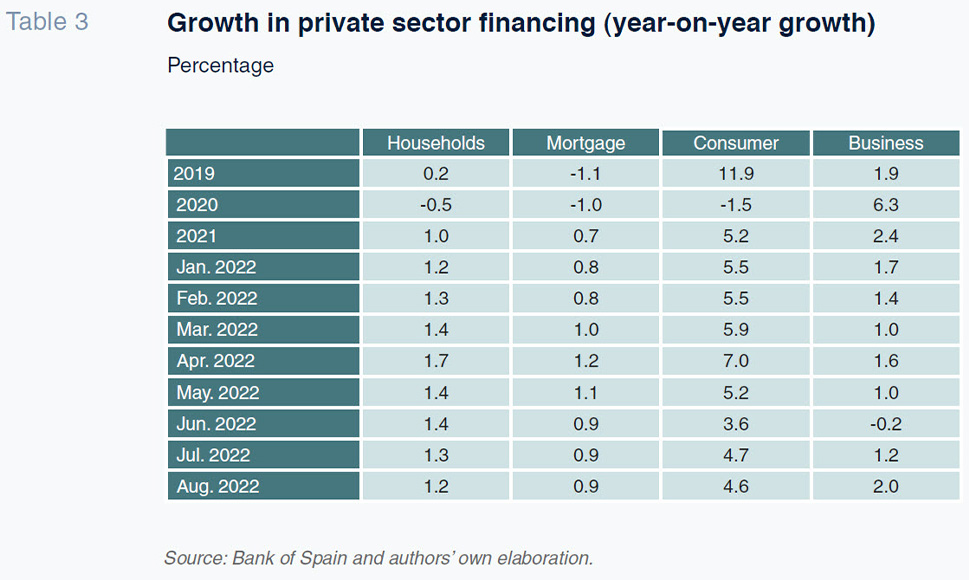

Despite that situation, demand conditions are not ideal and the supply of credit, while growing, remains very subdued. The data tracking financing flows to the private sector corroborate that conclusion (Table 3). Loans to households registered year-on-year growth of 1% in 2021, rising further to 1.7% in early 2022; however, the newfound uncertainty has given way to a new phase of cooling, with household lending growing by 1.2% in August, the latest figure available. Most of that growth was concentrated in consumer finance which, despite a considerable slowdown, registered year-on-year growth of 4.6% in August, compared to growth of 0.9% in home loans.

As for business lending, the trend is less consistent. In the wake of notable growth in 2020 (6.3% year-on-year), fuelled by the support and public guarantee schemes rolled out during the pandemic, growth in lending has slowed significantly as well as becoming more volatile, contracting for example by 0.2% in June only to register growth of 2% in August.

Conclusions

Rising interest rates are translating into a significant increase in borrowing costs over a short period of time. This paper highlights that trend at both the eurozone and Spanish levels, yielding a few noteworthy conclusions:

- Rates have increased in just a few months by a magnitude that in more orthodox policy shifts would normally take place over a longer period of time. While current rates remain moderate by historical measures, the contrast with the situation during the run-up to the financial crisis makes the increase striking.

- Rates on the most common kinds of loans are fairly similar across the eurozone and the rates prevailing in Spain are in line with the averages. In general, the increase in rates has been accompanied by a slowdown in lending, particularly in the consumer finance segment.

- In Spain, the banks are reporting growth in profits and improved solvency; however, returns remain slim. Lending has slowed in the wake of the efforts made to keep credit flowing to the private sector, particularly to the business segment, during the pandemic. The increase in interest rates is already materialising in a degree of retrenchment in lending activity, particularly in the mortgage segment.

Notes

Santiago Carbó Valverde. University of Valencia and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas