General Budget and Budgetary Plan for 2023: A comprehensive analysis

An analysis on the 2023 Budget reveals there is little justification for concern over its consistency and sharply expansionary nature, failure to comply with the country-specific recommendation (CSR) or any mismatch between public spending and revenue. Nonetheless, a more accurate assessment of Spain’s public finances for 2023 will ultimately depend on the details and costs of the forthcoming package of additional fiscal measures for that year due to the war in Ukraine.

Abstract: While the 2023 Budget presented in early October is a vital document, the 2023 Plan presented to the European Commission one week later provides a more holistic approach for an analysis that takes into account upcoming fiscal measures designed to help vulnerable households and firms, which are set to have a material impact on both the revenue and expenditure sides of the budget equation. Indeed, the 2023 Budget starts from a 2022 tax revenue forecast clearly below the level derived by extrapolating tax collection figures available to date, which means that the rate of growth in tax revenues needed to deliver the forecast contemplated in this document will be much lower. Given that the government continues to target an overall public deficit of 3.9% in 2023, the figure established in the 2022-2025 Stability Programme presented last spring, the required deficit reduction will be much smaller, around one third of the initially contemplated amount. In short, per the 2023 Budget, there is little justification for concern over its consistency and sharply expansionary nature, failure to comply with the CSR or any mismatch between public spending and revenue. The healthy momentum in tax revenue in 2022 means the deficit and tax collection targets for 2023 are very modest and achievable, even if the macroeconomic situation ends up far worse than the government is forecasting. Nonetheless, the 2023 Budget is undermined by its omission of the fiscal package to be deployed in 2023 in response to the energy and inflation crisis which means that a more accurate assessment of the state of Spain’s public finances in 2023 ultimately depends on the details of this package and its estimated cost. The probability of an economic downturn and the potential for a greater gap between revenues and costs thus calls for a highly selective package of additional fiscal measures to allow for some discretionary measures in case new needs emerge over the coming quarters.

General budget or budgetary plan?

The general state budget for 2023 (2023 Budget), presented on October 6th, 2022, before Congress, creates an analytical dilemma: whether to focus on an analysis of its figures, or alternatively, prioritise the 2023 Budgetary Plan of the Kingdom of Spain 2023 (2023 Plan) sent a week later, on October 15th, to the European Commission (Ministry of Finance and Civil Service, 2022a and 2022b).

Naturally, for micro-analytical purposes, with its focus on spending programmes and projects, the 2023 Budget is a vital document. However, the Plan is a better source for a holistic approach focused on internal consistency, between revenue and expenses, and external consistency, with the macroeconomic environment. Moreover, the Plan also allows for an analysis that takes into consideration the latest figures and information about probable or highly probable developments on both the revenue and spending sides of the budget equation. For the first time in history, the 2023 Plan, includes two scenarios.

The so-called Scenario 1 encompasses all the revenue and spending measures featured in the 2023 Budget, and the core aspects of the draft budgets for the regional governments for 2023. Scenario 2, meanwhile, layers in a package of revenue and spending measures, not yet defined and passed, designed to protect the households, workers and companies most affected by the crisis. In other words, a sort of selective rollover of the initiatives deployed in 2022. The second scenario also factors in the expected revenue from the new tax on large fortunes, currently making its way through parliament (1.5 billion euros), and the upside in corporate tax revenue unlocked by the limit on the ability to offset tax losses agreed by the coalition government at the end of September (244 million euros).

Revenue performance in 2022

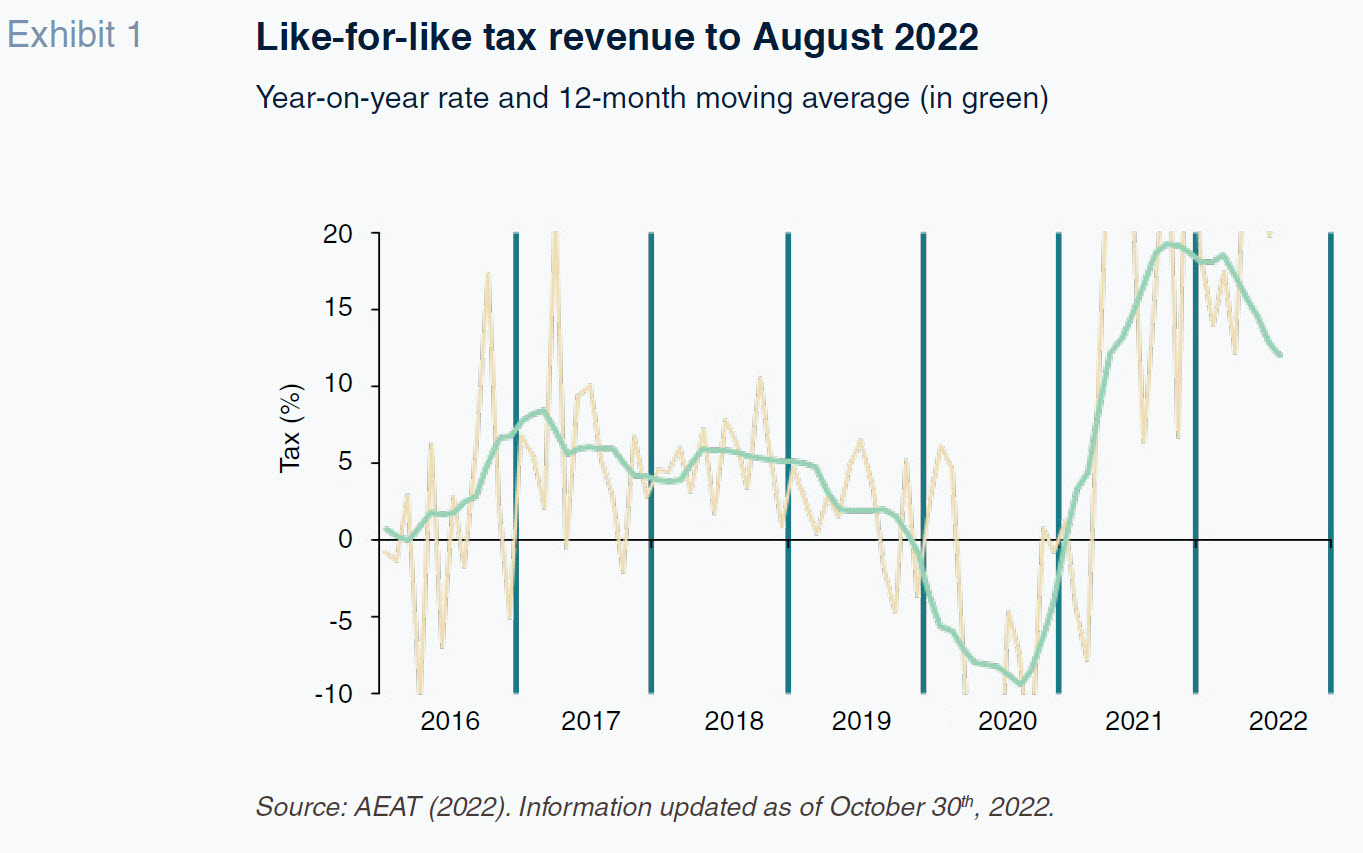

The 2023 Budget starts from a tax revenue forecast for 2022 that is clearly below the level derived by extrapolating the tax collection figures available to date (Exhibit 1). Tax revenue between 2020 and 2022 has trended systematically above the level that might be expected in light of the GDP growth recorded. Several factors underpin that outperformance: the effect of income support measures, such as the furlough scheme, which have eased the correlation between GDP dynamics and household income, particularly in 2020 and 2021; inflation for the past year, which very swiftly increases VAT tax bases and then more gradually inflates those of the direct taxes; a strong job market, which has done away with the threshold of GDP growth of 2% needed for robust job creation in Spain; and the shrinkage of the shadow economy, thanks to the mainstreaming of digital payment methods and greater awareness on the part of the economic agents of the costs of living in the informal economy when it comes to accessing protection schemes of various kinds.

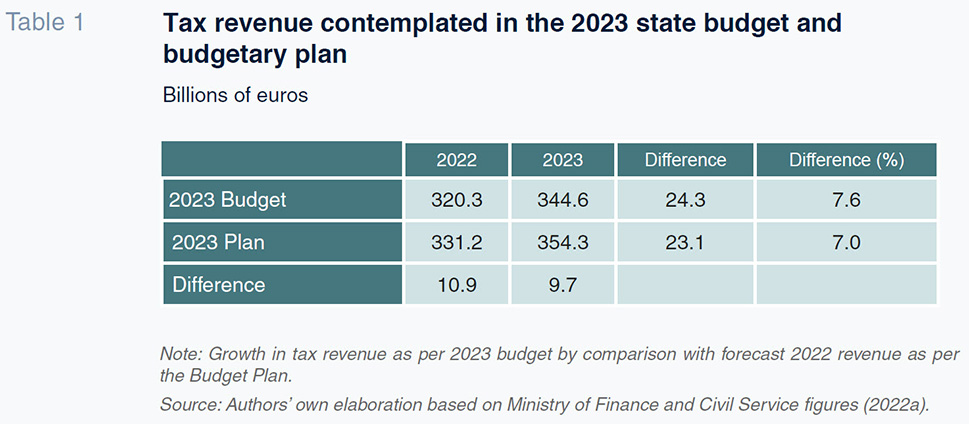

What that means is that the starting point will actually be significantly higher so that the rate of growth in tax revenue needed to deliver the forecast contemplated in the 2023 Budget will be much lower. Table 1 makes that point clearly. If we use the 2022 figures contemplated in the budget as our reference, tax revenue is forecast to grow by 7.6% in 2023, above the growth in nominal GDP forecast by the Spanish government (6.0%), Bank of Spain (5.9%) and Funcas (5.1%).

[1] However, if the starting level is that contemplated in the 2023 Plan, which extrapolates the collection data reported by the tax authorities through October, that percentage narrows to merely 4%. The first figure implies a revenue elasticity of over 1, whereas the second implies an elasticity of well under 1 and is therefore conservative. Particularly in light of the fact that there are new taxes looming: excise duty on plastic packaging and new temporary levies in the energy and financial sectors. According to the 2023 Plan, the aggregate revenue from those new taxes is estimated at 3.99 billion euros, which is more than twice the net cost of the changes in personal income tax, VAT and corporate income tax included in the fiscal package agreed by the coalition government on September 30

th (1.81 billion euros).

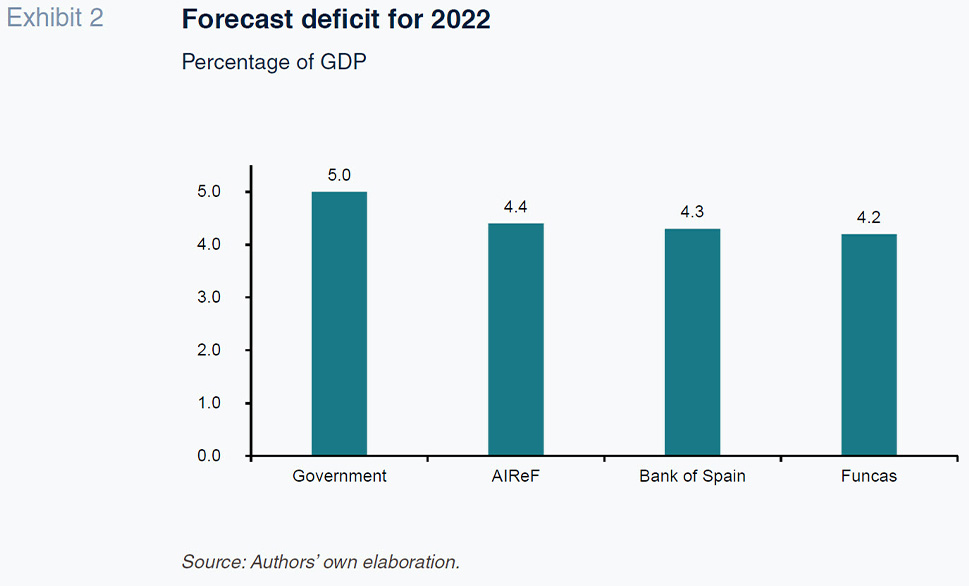

The extraordinary revenue dynamics also has a direct impact on the deficit forecast for 2022. Compared to the 5% of GDP featured in the 2023 Budget, the Bank of Spain is forecasting a deficit of 4.3%; AIReF, a deficit of 4.4% and Funcas one as low as 4.2%, helped by the interplay of the automatic stabilisers and inflation (Funcas, 2022). In other words, between 0.6pp and 0.8pp lower (Exhibit 2).

Given that the government continues to target an overall public deficit of 3.9% in 2023, the figure established in the 2022-2025 Stability Programme presented last spring, the required deficit reduction will be much smaller, around one third of the initially contemplated amount. In the words of the Governor of the Bank of Spain: “that target [of 3.9%] seems feasible, taking into account, in particular, that the budget deficit will likely be below the official estimate in 2022 (by some 0.7pp)” (Hernández de Cos, 2022).

[2] Funcas (2022) is less optimistic. It believes the cooling of the economy and indexation of pensions to actual CPI will send the deficit slightly higher in 2023, to 4.4%. On the other hand, AIReF is projecting a much lower deficit (3.3%), although its number does not contemplate the potential full or partial rollover of the package of fiscal measures in response to the energy and inflation crisis.

Thirdly, it is important to analyse the rate of growth forecast in primary current expenditure and its alignment with the country-specific recommendation (CSR) made by the European Commission (2022). Although the European fiscal rules remain suspended in the wake of the decision to extend the escape clause until 2024, those recommendations are an important element for an interim assessment of Spain’s commitment to fiscal stability and, by extension, the coverage potentially afforded by the ECB’s new anti-fragmentation tool, the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). The TPI replaces the extraordinary bond purchase programme implemented in response to the pandemic and is vital to preventing volatility in country risk premiums in line with those observed a decade ago.

In essence, the CSR seeks to limit growth in current primary expenditure financed at the national level to less than the medium-term rate of growth in nominal GDP. The measures implemented to support businesses and households in the face of the energy crisis and support refugees fleeing the war in Ukraine are carved out from that capped expenditure. Although it is not yet clear which figure the European Commission will use for Spain, specifically which GDP deflator it will choose for its calculations. The government is estimating a cap of 4.6% in its 2023 Plan, while forecasting growth in qualifying expenditure of 4.4%. The AIReF’s assessment (2022) is compatible with that of the government. The independent fiscal institution maintains that the CSR for Spain will be somewhere between 3.1% and 5.1%, depending on the deflator ultimately selected, and its estimation of the growth in qualifying expenditure (+3.6%) is close to the lower bound of that range.

[3]

Lastly, our analysis requires studying structural deficit dynamics, and, by extension, the tone of fiscal policy in 2023. A reduction (increase) in the structural deficit is interpreted as a contractionary (expansionary) bias. Right now, it is particularly difficult to break the public deficit down into its structural and cyclical components. In its 2023 Plan, the government argues that the structural deficit will fall from 3.7% in 2022 to 3.4% in 2023 in both of the scenarios modelled in the document, implying that fiscal policy will be slightly contractionary in 2023. In his speech before Congress on the topic of the 2023 Budget, the Governor of the Bank of Spain cast some doubt over that forecast. In his opinion, the structural deficit will be similar in 2022 and 2023, implying a neutral fiscal policy stance. He also sparked an interesting debate about the advisability of factoring in the European funds channelled through the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) when it comes to assessing the structural fiscal balance. Although those funds do not affect the deficit in accounting terms, they do affect the tone of fiscal policy, so that: “in order to correctly measure the fiscal policy stance, the change in the structural balance should be corrected for this effect, deducting the change in the net balance of funds received from the European Union” (Hernández de Cos, 2022). On that basis, the Bank of Spain concludes that Spain’s structural deficit will increase slightly – by around 0.15 percentage points – in 2023.

In short, if we focus our analysis on the 2023 Budget, there is little justification for concern over its consistency and sharply expansionary nature, over failure to comply with the CSR assigned to Spain or over any mismatch between public spending and revenue dynamics. The healthy momentum in tax revenue in 2022 means the deficit and tax collection targets for 2023 are very modest and achievable, even if the macroeconomic situation ends up far worse than the government is forecasting.

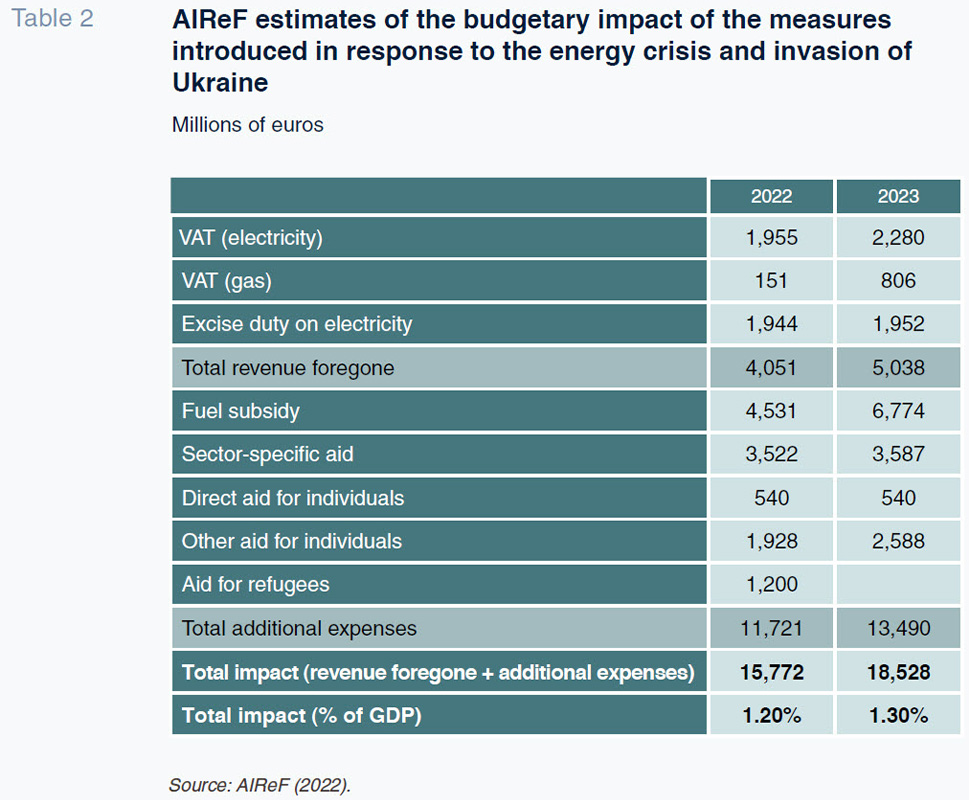

Extension of the Ukraine fiscal package: A key consideration

It is true, however, that the 2023 Budget is undermined by its omission of the fiscal package to be deployed in 2023 in response to the energy and inflation crisis. As a result, the assessment of the state of Spain’s public finances in 2023 ultimately depends materially on how that package materialises and its estimated cost. Over the coming weeks, the coalition government needs to come up with an effective solution in terms of results that is financeable and consistent with the room for fiscal manoeuvre available in an environment that is deteriorating. With a view to identifying the related limits and possibilities, Table 2 reproduces AIReF’s estimates (2022) of the fiscal cost of the main measures taken in 2022 and of their hypothetical rollover to all of 2023. [4]

The extension to 2023 of all of the measures would imply an expenditure cost of 13.49 billion euros, which is equivalent to nearly one point of GDP, while the revenue foregone comes to 5.04 billion euros, a little over 0.3pp of GDP. In addition, the government is expected to continue to take new decisions between now and the end of the year, such as extension of subsidised gas and electricity rates or the creation of a new regulated tariff for housing blocks with natural gas boilers, measures announced in October.

Meanwhile, Scenario 2 of the 2023 Plan contemplates an identical increase in non-financial spending and revenue as in Scenario 1: 0.7pp of GDP, equivalent to 9.7 billion euros, to leave the deficit in line with that contemplated in the 2023 Budget. Depending on where tax revenue ends up this year, the probability of a downturn in the economic situation and the distance between the costs projected in the paragraph above and the room for manoeuvre in Scenario 2 highlight the need to limit the magnitude of the fiscal package in 2023. It would be reasonable and prudent to be highly selective. And it would be advisable not to use up all of the slack by December in case new needs emerge over the coming quarters.

In making that selection it is essential to evaluate the measures in detail along at least four dimensions: their cost; their distributional impact; their negative or positive impact on the energy transition thrust; and their fit with the recommendations made in the white book on tax reform.

[5] Framed by those criteria, two measures look like obvious candidates for reduction or elimination: the fuel subsidy and the electricity and gas VAT rate cuts. The fuel subsidy represents nearly half of projected expenditure (almost half a point of GDP); on the whole, its distributional impact is regressive; and it works against the country’s decarbonisation goals. The reasons for eliminating the VAT discount are similar; plus, that initiative is out of sync with the white book recommendations. Unquestionably, it will be hard to roll back those measures from an economic policy standpoint. Definition of scenarios for their gradual elimination is one possible solution. It might also make sense to focus on productive sectors that are unable to switch technology in the short-term (

e.g., transport, fishing) from elimination of the fuel subsidy.

Notes

The differences are higher in relative terms if we look at real GDP growth. All of the forecasts are below the 2.1% projected by the government: 1.5% according to AIReF (2022) and OECD (2022); 1.4% as per the Bank of Spain; 1.2% in the opinion of the IMF (2022); and 0.7% according to Funcas (2022). To the contrary, the GDP deflator, the other component of nominal GDP, is below that forecast by the government.

The Governor added that “the new measures announced after the Banco de España’s macroeconomic projections were published on October 5th and would not have a significant impact on the deficit forecast for 2023.”

The AIReF has warned that matters will be different in the event that all of the measures passed in 2022 to tackle the energy crisis are extended to 2023. In that event, current primary expenditure would grow by close to 6.9%, which is clearly outside that band. However, as noted earlier, the extension of the fiscal package encompassing measures to mitigate the energy crisis and invasion of Ukraine will conceivably not compute for CSR limit purposes.

The table leaves aside the suspension of the levy on the value of electricity generation as the revenue foregone affects the amounts transferred to the sector watchdog (the CNMC), with a neutral impact on the deficit. The 2023 Plan provides a full list of the initiatives undertaken, including those that do not have a direct impact on the budget.

The estimates compiled by Checherita-Westphal, Freier and Muggenthaler (2022) for the eurozone countries reveal two characteristics of the aid deployed to tackle the energy and inflation crisis up until the summer of 2022. Firstly, their untargeted nature. Just 12% of the measures are focused on the most vulnerable households. Secondly, just 1% of the measures make a positive contribution to the green transition and decarbonisation.

Referencias

AEAT. (2022).

Monthly Tax Collection Reports. June 2022. Retrievable from:

https://sede.agenciatributaria.gob.es/

Sede/datosabiertos/catalogo/hacienda/Informe_mensual_de_Recaudacion_Tributaria.shtmlAIReF. (2022).

Report on the projects and fundamental lines of the budgets of the public administrations: General State Budgets 2023. October 18

th. Retrievable from:

www.airef.esBANK OF SPAIN. (2022).

Macroeconomic projections for the Spanish economy (2022-2024), October 5

th. Retrievable from:

www.bde.esCHECHERITA-WESTPHAL, C., FREIER, M. and MUGGENTHALER, P. (2022). Euro area fiscal policy response to the war in Ukraine and its macroeconomic impact.

ECB Economic Bulletin, 5/2022. Retrievable from:

https://www.ecb.europa.euEUROPEAN COMMISSION. (2022).

Council Recommendation on the 2022 National Reform Programme of Spain and Delivering a Council Opinion on the 2022 Stability Programme of Spain, May 23

rd. Retrievable from:

www.ec.europa.euFUNCAS. (2022).

Spanish Economic Forecasts Panel.

November 2022. Retrievable from:

www.funcas.esHERNÁNDEZ DE COS, P. (2022).

Testimony before the Parliamentary Budget Committee in relation to the Draft State Budget for 2023. Congress of Deputies. October 17

th. Retrievable from:

www.bde.esHERRERO, C. (2022).

Appearance before the Budget Committee of the Congress of Deputies. Report on the Main Lines of the Budget of the General Government: 2023 Draft General State Budget. October 18

th. Retrievable from:

www.airef.esIMF. (2022).

World Economic Outlook. October. Retrievable from:

www.imf.orgOECD. (2022).

OECD Interim Economic Outlook GDP Projections. September. Retrievable from:

www.oecd.orgSPANISH MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND CIVIL SERVICE. (2022a).

Presentación del Proyecto de Presupuestos Generales del Estado 2023 (Libro Amarillo) [Presentation of the Draft National Budget for 2021 (Yellow Book)]. October 6

th. Retrievable from:

www.hacienda.gob.esSPANISH MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND CIVIL SERVICE. (2022b).

Budgetary Plan for the Kingdom of Spain 2023. October 15

th. Retrievable from:

www.hacienda.gob.es

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics at Vigo University and Senior Researcher at Funcas