The global economy in times of polycrisis

2022 was characterised by uncertainty, economic and financial markets volatility, and most importantly, an acceleration in the regime shift in which the global economy is immersed. Although many questions remain unanswered, 2023 should shed some more light on key future international economic trends, with the search for a new equilibrium in prices, economic policy and geopolitics the main variables to watch.

Abstract: The global economy is heading into the new year trying to digest the nasty surprises ensuing since the beginning of 2020, which have ushered in the biggest imbalance between supply and demand of recent decades. The pandemic, the bottlenecks in international shipping, the war in Ukraine and the surge in energy prices have altered the dynamics that have driven business cycle patterns since the financial crisis of 2008. That accumulation of shocks is proving a challenge for economic policy response in the short-term and threatening to alter the ecosystem in which the global economy has been moving since the end of the 1970s, characterised by flexibility and maximisation of production efficiency via global value chains. Although there are more questions still than answers about how this process will play out and a good number of fronts are still open, 2023 should shed some more light on key future international economic trends. While it is too soon to rule out the odd quarter of contraction in one of the major economic blocs, current signs point more to a relatively soft economic landing, without traumatic effects on employment, rather than to a full-scale recession. Indeed, the global economy could grow by around 2.5% in 2023, although with a significant slowdown in growth in both advanced economies and emerging economies. In the near-term, the key lies with the trend in inflation, the real barometer for the instability sustained by the economy in recent years. The search for new equilibriums in prices, economic policy and geopolitics will be among the main variables to watch in 2023.

Times of change for the international economy

2022 marked another twist in the plot that has been jolting the global economy since the onset of the pandemic. In early 2022, the economic climate continued to be marked by limited global supply on account of bottlenecks in transportation and logistics and demand whetted by both the recovery in mobility and the savings set aside during the pandemic. Although that mismatch started to push prices higher in the spring of 2021, the central banks initially opted not to respond to the spike in inflation, trusting that it would prove transitory and that supply would catch up with consumers’ new preferences. Indeed, as late as in December 2021, the financial markets were not really discounting interest rate increases in the following 12 months. Despite the complex environment, there was faith that things would return gradually to normal once the most virulent stage of the pandemic was behind us.

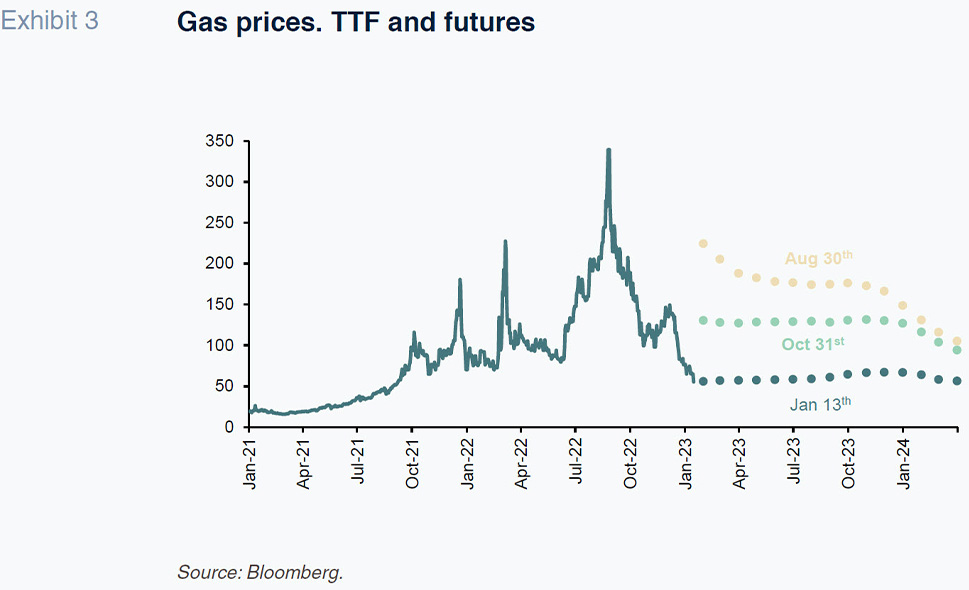

Everything changed on February 24th, when Russian troops invaded Ukraine. The new supply side shock caused by the ensuing surge in energy prices and the uncertainty caused by the first major armed conflict on European soil in the twenty-first century threatened to unleash a process of global stagflation, particularly when natural gas prices approached €350/MWh at the end of August, following the announced closure of the main gas pipelines bringing gas from Russia to north-eastern Europe. For much of last year, therefore, the feeling was that the international economy was facing its biggest challenge in recent decades due to the existence of multiple, disparate and overlapping shocks which threaten to alter dynamics across the main economic variables. In the words of the historian, Adam Tooze, we are facing a polycrisis, a diversity of simultaneous shocks which interact with each other, in which the “whole is more overwhelming than the sum of the parts”. [2]

That sensation of exceptional economic conditions was borne out in surprising trends in a good number of economic and financial variables. In 2022, we saw inflation in the OECD reach its highest levels in nearly four decades (topping 10% towards the end of the summer), Germany report its first trade deficit since 1981 and the dollar appreciate to levels not seen in recent decades against currencies of the calibre of the sterling (37-year high) and the yen (32-year high).

In short, the changes engulfing the international economy since 2020 only intensified last year. The key characteristics of that process of change include:

- The biggest gap between global supply and demand since the end of the 1970s. The disruption caused by the pandemic has coincided with the effects of the expansionary fiscal programmes set in motion in the spring of 2020, creating significant imbalances in the goods and services markets. Although those imbalances narrowed over the course of 2022 thanks to economic cooling and gradual resolution of the bottlenecks, their effects will take time to dissipate.

- Transformation of the globalisation process due to factors such as increased political risk and the value chain fragility exposed. Although the first symptoms emerged at the beginning of the financial crisis, when the percentage of GDP accounted for by goods and service exports peaked (2008), the events of the past three years have triggered a boom in concepts such as “strategic autonomy”, “friend-shoring” and “nearshoring”. That search for supply security at the cost of efficiency and, as a result, the attempt to bring some production back home, is beginning to be seen in the economic policy programmes being devised on both sides of the Atlantic since the onset of the pandemic. The risk is the potential for the abuse of aid and benefits for national companies in the process, with legitimate medium-term objectives such as digitalisation and energy transition masking protectionism. The biggest exponent of that new economic policy thrust was the last plan passed by the Biden Administration (US Inflation Act) last summer, which sets aside $80 billion of aid for production on American soil-a move that is bound to trigger a response by the European Commission in the form of an updated aid framework for regional companies. The risk is, therefore, that we could go from a phase of strategic autonomy to one of all-out strategic competition between economic blocs.

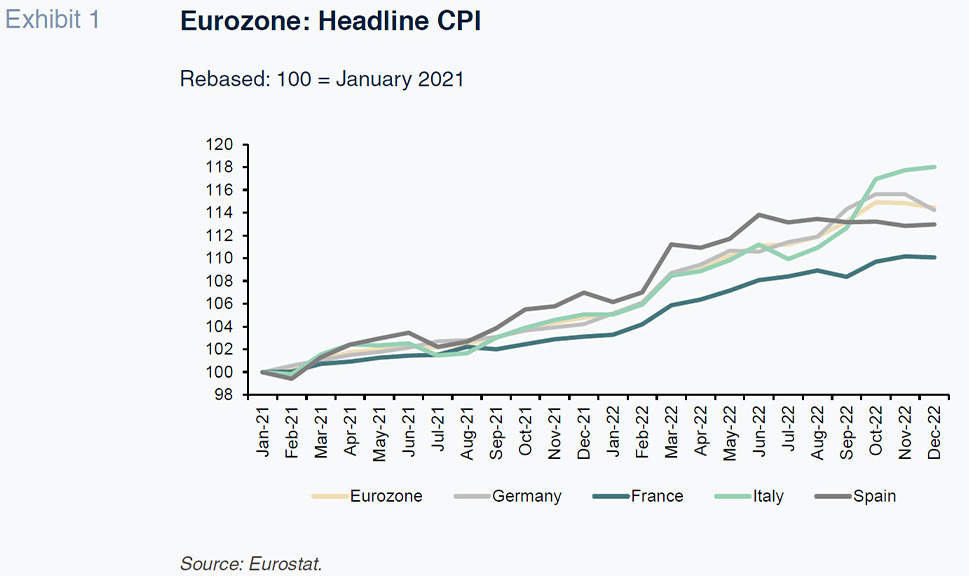

- A regime change in inflation. After nearly 15 years of prices trending below central bank targets, in 2022, inflation hit a decades-long high due to the cumulative impact of: production bottlenecks; rising energy and food prices; an accelerating energy transition (greenflation); and, the effects of several years of largely unchecked monetary and fiscal expansion. Moreover, core inflation is already running at around 5% or 6% and showing scant signs of coming down in the near-term, evidencing how the more volatile components of CPI are beginning to have a very considerable impact on the other components. That drastic shift in the inflation trend threatens to erode household purchasing power, increase inequality, trigger sharp financial market corrections and/or increase the risk of financial instability, among other risks.

The positive reading is that the root of all these problems – bottlenecks at the earliest stages of the production process – is beginning to show signs of normalisation, which, coupled with a reduction in energy prices, has been pushing headline inflation lower in recent months. The big question is how long it will take for inflation to return to 2% and, therefore, affect central bank decision-making. And, more importantly, how will inflation trend after the impact of the various shocks has been digested. That will determine the fit for purpose of targets that have been in use for nearly four decades and of the strategy designed right before the pandemic, when the central banks’ problems were exactly the opposite of those faced today.

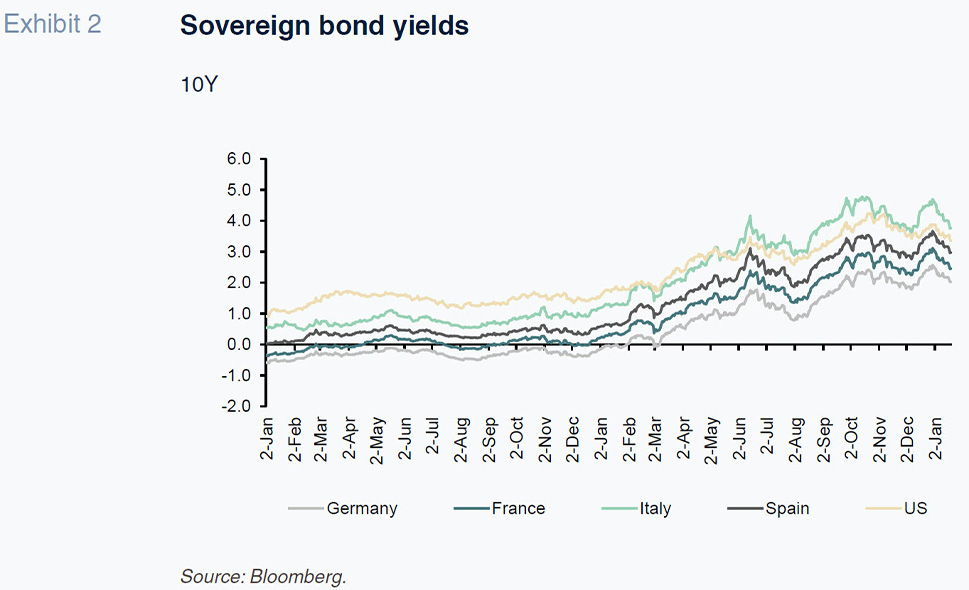

- The most intense monetary policy normalisation effort of recent decades, with the central banks jumping from denial to action (or even overreaction). The monetary authorities’ response across both developed and emerging economies has implied a cumulative increase in interest rates since the end of 2021 of close to four percentage points. According to the Bank of International Settlements in Basel, 2022 marked a record for rate increases (200 increases of 25 basis points), smashing the last record which dated back to 2006 (120 increases). That means monetary policy is contractionary in a large swath of countries. The good news is that financial tightening has taken place in the absence of worrying episodes of financial stability (with the exception of the mini crisis in the UK), despite a sharp correction all year long in the bond and equities markets. [3]

- Marked labour market resilience. In nearly all major economies, employment levels are above those of 2019 and in many cases unemployment rates are near record lows (3% in Germany). Indeed, the biggest miscalculation in the forecasts published towards the start of the pandemic was the prediction of significant job losses in the short- and medium-term. The snapshot three years on is very different from that anticipated. In fact, the problem in many areas of the OECD labour market is a significant number of vacancies and (once again) the inability of supply to react to demand. It seems clear that the healthy employment dynamics are largely underpinned by the various furlough schemes in Europe (emulating Germany’s Kurzarbeit scheme) which preserved ties between companies and employees throughout the crisis. However, we are beginning to see structural changes related with the pandemic (working from home), demographics (the baby boomers are beginning to retire and the pool of newcomers is much smaller) and even sociological factors (the Great Resignation).

- The end of the economic policy measures applied during the pandemic. The combo of ultra-lax monetary and fiscal policies is over. The very nature of the supply shocks, which are affecting inflation differently from growth (fuelling the former and weighing on the latter) is driving divergence between fiscal and monetary policy. In times such as these, neglecting budget discipline by pursuing unchecked fiscal policies would make it harder for the monetary authorities to attain their goals and increase the risk of financial accidents. The free bar is closed and the markets will not tolerate stepping on the accelerator and break at the same time, as was made clear during the crisis in the UK last September.

In sum, 2022 was once again characterised by unpleasant surprises of all kinds, uncertainty and volatile economic and financial variables. Above all, however, it was marked by an acceleration in the regime shift in which the global economy is immersed.

2023: In search of a new equilibrium

Although the international economy has rung in the new year with weak vital signs, there are symptoms of improvement in the various macroeconomic imbalances, pending the outcome of the economic cooling underway in the three major economic regions (US, China and the eurozone). For now, it looks as if the scale of economic deterioration feared towards the end of 2022 has not materialised thanks to labour market resilience, favourable energy price trends in the last quarter, stabilising expectations following their collapse when the war broke out and the delayed effects of the expansionary fiscal measures rolled out at the height of the pandemic (pent-up savings, NGEU funds, etc.).

The good news, therefore, is that the probability that the sharp slowdown in GDP growth will end in a global recession in the first half, as was feared at the end of the summer, is diminishing. The sense is that the economy is absorbing the effects of the supply shocks, heightened geopolitical risk and interest rate hikes much better than expected. Meanwhile, concern over the energy scenario has abated because at this stage of the winter the spectre of gas rationing in Europe can be virtually ruled out because: current gas reserve levels are high (over 85%), gas consumption is falling considerably (by 10% between January and November by comparison with long-run levels) and LNG is flowing into Europe at a dynamic pace. In fact, gas futures for 2023 have plummeted from nearly €190/MWh at the end of August to €70 euros/MWh as of the first half of January, with the spot price hovering around €50/MWh during some trading sessions. In parallel, oil prices have largely stabilised at around €80-90/bbl, implying a substantial improvement in the energy price assumptions used in economic forecasting exercises undertaken barely three months ago (more than offsetting the impact of the unexpected increase in rates).

Therefore, although it is too soon to rule out the odd quarter of contraction in one of the major economic blocs, current signs point more to a relatively soft economic landing, without traumatic effects on employment, than to a full-scale recession. Indeed, the global economy could grow by around 2.5% in 2023, shaped by a significant slowdown in growth in both advanced economies (1% vs. 2.4% in 2022) and emerging economies (4% vs. 7% in 2022). Given the scant visibility at present, it is hard to extrapolate the business cycle profile but logic would dictate that this quarter will be the weakest in Europe, whereas in the US the effects of the Fed’s rate increases are likely to be felt more towards the spring and summer. That being said, the current forecasts are framed by significant volatility as they are conditioned by a range of disparate factors including the reopening of China, events in Ukraine and the sensitivity of financial stability to the central banks’ last movements until they reach their terminal rates given that public and private borrowing levels are so high.

In the short-term, the key lies with the trend in inflation and, by extension, the speed with which the current imbalances correct. The number of pleasant surprises in the latest inflation readings mark a shift with respect to the panorama just a few months ago. All signs suggest that the initial phase of price correction could be complete by this summer, with inflation closing in on 4% in the US and EMU alike. That will not necessarily be sufficient for the central banks, especially if the news about the trend in the key components is not good. The doubts being voiced by the monetary authorities (especially the ECB) about the second phase of the disinflationary process to reach the targeted 2% will shape the entire economic scenario in 2023 and 2024. It is not the same if the central banks complete their rate tightening in the first half of this year at levels close to those currently being discounted by the market (3.25%-3.5% in the EMU and 4.75%-5% in the US) as if there is another acceleration of tightening. By the same token, monetary stability requires governments and central banks to coordinate more intensely. It is not easy to move from a situation akin to fiscal dominance to one in which short-term macroeconomic stability is once again a priority.

As a result, the search for new equilibriums in prices, economic policy and geopolitics will be key in 2023 – a year which should start to paint a picture of what the new economic normal will look like once the recent instability is a thing of the past. During the transitory phase, in which the old is dying and the new cannot be born, we will continue to witness major debates, such as China’s role over the coming decade, the limits to global indebtedness, the future of globalisation and the implications of the energy transition process.

Notes

Christine Lagarde herself virtually ruled out the possibility of interest rate increases in 2022 at her press conference following the ECB Governing Council meeting of December 2021.

“Welcome to the world of polycrisis” – Financial Times (October 28th, 2022).

Losses on 60/40 portfolios topped 15%.

José Ramón Díez Guijarro. CUNEF