Corporate finance: Banks versus capital markets

Tension in the corporate bond market since the start of the inflationary spiral towards the end of last year has driven a sharp increase in secondary market rates, as well as a sharp contraction in primary market issuance, forcing many corporates back to the bank financing channel they had previously abandoned. Nonetheless, rather than seeing this development as a setback, it reflects the complimentary rather than substitutive nature of bank and market corporate financing, with the banks acting as a back-up option when the bond markets are temporarily unable to finance the productive apparatus.

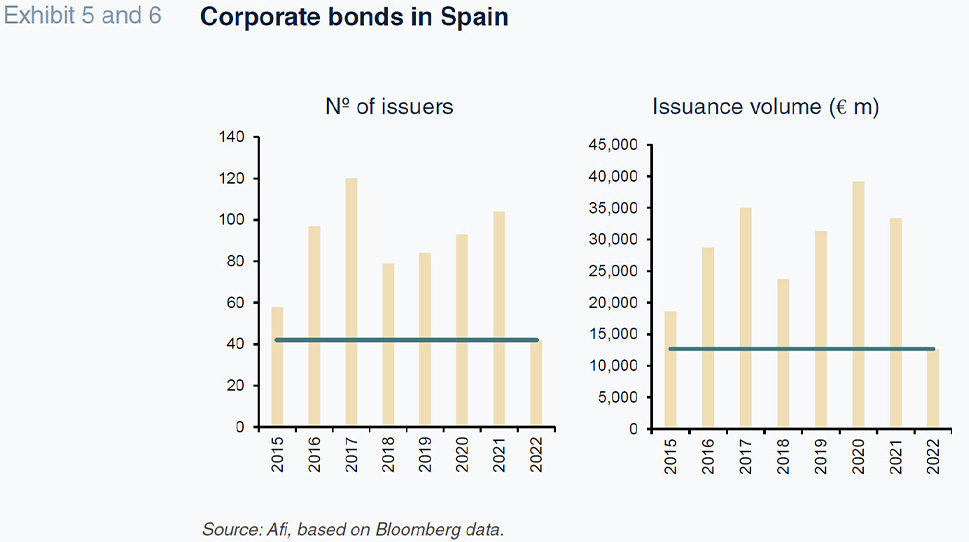

Abstract: It has long been assumed that corporate financing in Spain (and Europe) was overly reliant on bank lending to the detriment of the capital markets, in contrast to the US model, where corporates tapped the markets far more intensely. To that end, in 2015, the European Commission launched its Capital Markets Union (CMU) initiative with the clear aim of correcting that bias, prompting a significant number of Spanish and European companies to début as bond market issuers. Tension in the corporate bond market since the start of the inflationary spiral towards the end of last year has driven a sharp increase in secondary market rates, as well as a sharp contraction in primary market issuance, making it impossible for many of those companies to tap the markets, forcing them back to the bank channel they had previously abandoned. That has led to a rebound in lending volumes to large enterprises, which are taking advantage of the fact that although the banks have increased the interest rates they charge for those loans, the increase has been less intense than the spike in market funding costs. As an example, activity in the Spanish corporate bond market, which had been registering strong growth since the middle of the last decade, in terms of both issuance volume and number of issuers, totally collapsed in 2022, accompanied by a very sharp increase in average yields on that market to over 4%. That said, indeed, bank and market corporate finance are compliments, rather than substitutes, with the banks acting as a back-up option when the bond markets are temporarily unable to finance the productive apparatus. The banks’ role is all the more noteworthy considering the fact that they themselves have also seen their ability to issue affected by the bond market crisis.

Banking  versus market oriented financial systems: Theoretical considerations

versus market oriented financial systems: Theoretical considerations

The banking system and capital markets constitute two core components of the financial system with each complementing the other. In the former, the financial intermediation function performed by the banks enables the aggregation of savings (deposits) of small amounts, placed for short periods of time, so as to extend loans of greater size and for longer terms. By means of that intermediation, the banks do the work of constantly monitoring borrowers on behalf of the lenders. Thanks to that function, the banks are better positioned than the capital markets to solve agency issues between borrowers and lenders and build the relationships of trust needed to underpin a bank loan.

Compared to those advantages, bank financing is less appropriate when borrowers do not have assets to pledge as security or a sufficient credit record or stable and predictable flow of income. That is the case of start-ups and companies that are looking to innovate or grow quickly. For them it is obvious that financing based on a range of capital markets instruments is more effective than bank financing.

In the literature on comparative banking systems, it is commonplace to distinguish between systems in which the banking channel is the dominant mechanism for financing the economy (banking-oriented) and systems in which, in contrast, funds are channelled directly through the securities markets (market-oriented).

Banks provide somewhat different financial services than the markets and a mix of both is needed to improve economic growth. The proportionate mix may vary as a function of the level of economic development, as well as aspects related with the legal framework. The response to which of the two models is most appropriate should be sought in the evidence obtained from international comparative studies. The most far-reaching of those studies is probably that conducted by Demirguc-Kunt, Feyen and Levine (2012) in which they analyse over 100 countries over a span of more than 30 years, controlling for spurious effects. That study concludes that as economies become more developed, they increase their use of the services provided by the securities markets, to the detriment of those furnished by the bank system.

Nevertheless, the influence of the financing structure on economic growth is markedly different during times of crisis compared to ‘normal’ situations. As underlined by Allen, Gu and Kowalewski (2017), market-oriented systems tend to deliver benefits for companies more reliant on financing during good times but disadvantage them during hard times. A good example is the so-called shadow banking system, which boosts economic growth but generates evident risks for the financial system and real economy.

That is evident in the analysis of the European experience during the last 15 years, a period marked by several crises, which have affected the mix of banking and market financing.

Market financing thrust in Europe: Capital Markets Union (CMU)

Traditionally, the Anglo-Saxon economies (US and UK, mainly) have been associated with greater market orientation, while the continental European economies are known for the weight of their banking systems. It was precisely to correct that bias and move the European financial system closer to the Anglo-Saxon pattern that the European Commission launched its Capital Markets Union (CMU) initiative in 2015, essentially an attempt to stimulate diversification of sources of financing at the SME level in order to reduce their excessive dependence on bank financing, as well as to spur the development of sources of long-term financing for infrastructure projects, of particular importance to the Juncker Plan, launched virtually in parallel with the CMU.

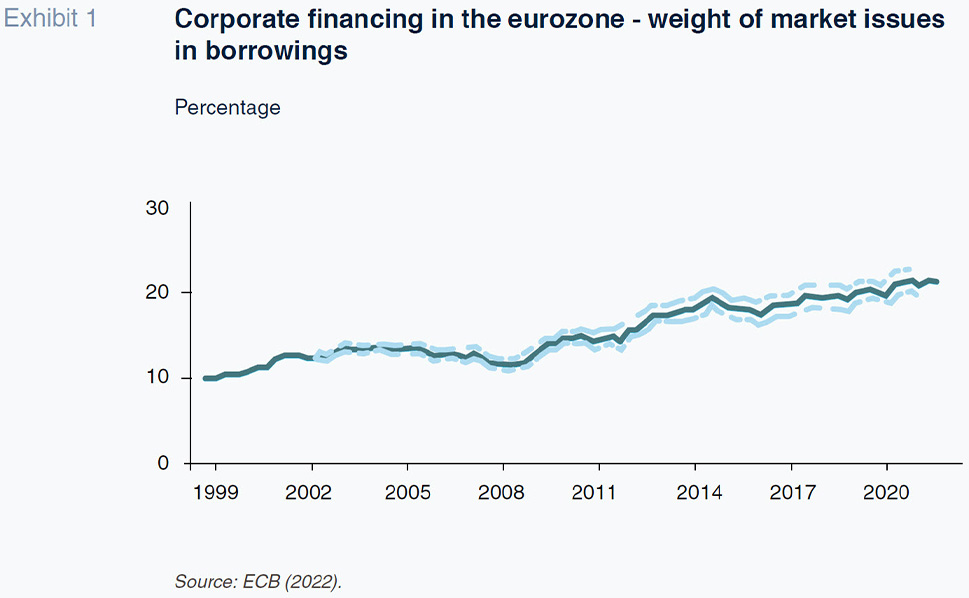

Regardless of whether attributable to the securities market impetus provided by the CMU initiative or to an element of contention in bank lending as the entities worked to shore up their asset quality in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, the weight of financing raised by non-financial corporates in the capital markets has increased significantly since the financial crisis. Exhibit 1, adapted from one published by the European Central Bank (2022), shows how the weight of capital markets financing has doubled in the fifteen years since the financial crisis, from 10% to almost 20%.

The ECB itself, in its interpretation of that trend, argues that companies resorted to the securities markets by way of “spare tyre” in response to the reduced supply of bank credit in the wake of the financial crisis, as the banks worked to provision for non-performing assets and shore up their capitalisation. Paradoxically, as we explain below, during the recent bond market crisis, the roles have reversed and now it is really the banks that are performing that “spare tyre” function.

In addition to increasing the aggregate weight of market financing, another objective was to boost the universe of companies tapping those markets by bringing in smaller-sized issuers for the first time, as noted by Darmouni-Paputsi (ECB, 2022). According to that study, between 2014 and 2018, more than 10% of the issues completed each year were undertaken by companies making their début on the bond markets.

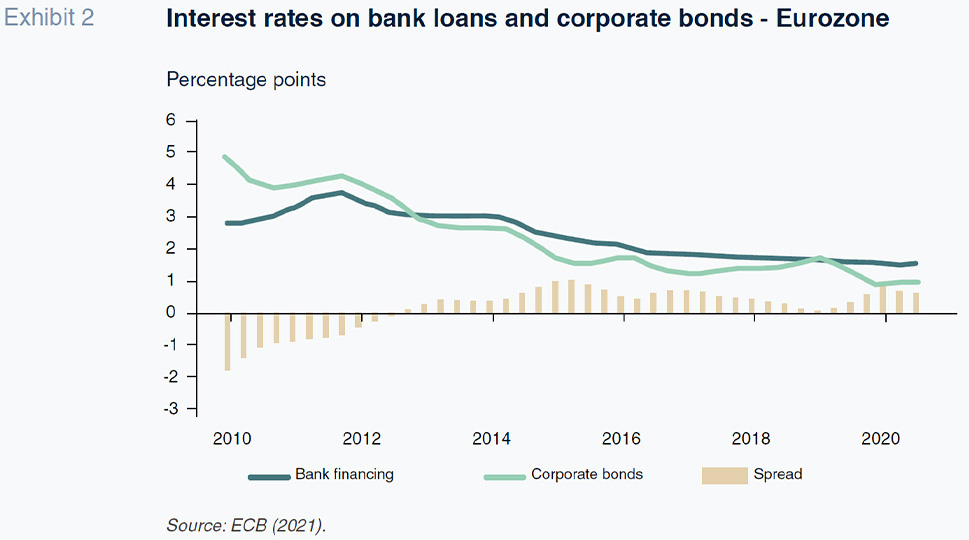

That growing use of the securities markets by European companies was accompanied in parallel by borrowing terms that trended lower in both absolute terms and in relation to the cost of bank loans, as illustrated in exhibit 2, taken from an ECB publication (2021). That exhibit likewise evidences how the spread between the cost of market financing and bank loans went from being negative (cheaper loans) during the initial years after the financial crisis to becoming systematically positive during the entire second half of the decade.

Bank financing as a plug for capital markets failures: The recent experience in Europe and Spain

That structural trend towards greater reliance on the markets, to the detriment of bank financing, is not exempt from risk, particularly during times of crisis, as acknowledged by the ECB, with the banks’ role as back-up becoming more patent than ever when the markets dry up.

It is worth noting that the use of the capital markets does not necessarily leave the banks less exposed to corporate financing, but rather forges a shift in the vehicle through which that exposure materialises. In fact, it is very common for bond issues by first-timers to be placed by banks, which tend to keep a sizeable chunk of the issues in their portfolios.

One ECB study (2022) reveals how at companies tapping the markets for the first time and unrated issuers, the banks emerge as the largest holders of their bonds, at over 20%. The banks’ presence as investors in the bonds issued by smaller-sized companies and companies with shorter trajectories constitutes a source of stability insofar as the banks are more patient investors that tend to hold on to their investments for longer periods of time.

That same ECB study shows how, in times of crisis and significant bond market volatility (for which it analysed the months of sharpest correction during the pandemic), the prices of the bonds of more established and liquid issuers tend to correct by more than those of smaller, less liquid companies. That effect is known as a ‘reverse flight to quality’, in the sense that the more active investors (mutual funds, asset managers) rush to sell off the bonds for which there is more liquidity and market depth, while the bonds issued by smaller companies are partially protected by the presence of more patient investors, especially the banks that helped them tap the markets in the first place.

That role played by the banks during times of crisis has been particularly evident during the past year in the context of the bond market crisis triggered by the surge in inflation, accelerated by the war in Ukraine. With bond yields rising sharply and issuer activity contracting severely, the banks have resumed their role as dominant corporate financier, particularly in the segments (large enterprises) where the issuers’ steady market presence may have suggested they no longer needed the banks.

That resurgence in bank financing (“back to basics”) is observable fairly generally across the various geographies but is particularly noteworthy in the US, the country where market financing has traditionally outweighed bank financing by the widest margins. As noted by the Federal Reserve in its last Financial Stability Report, bank financing for corporates has registered growth of 19% in the past year, compared to a meagre 1.5% in corporate bond issuance, so reversing the trend observed during the previous two decades.

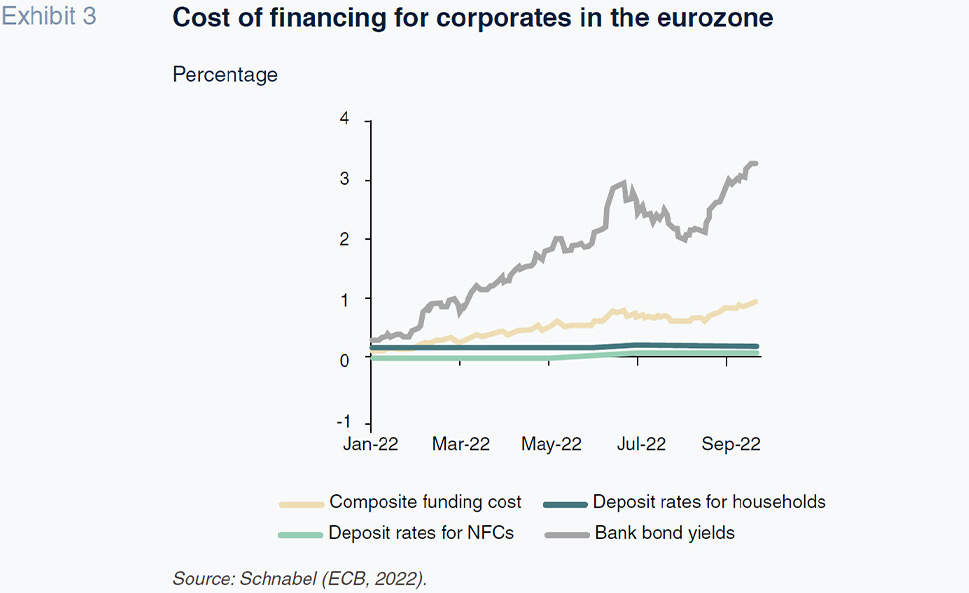

Turning to the eurozone, the sharp spike in interest rates sustained at the longer ends of the euro yield curve has translated speedily into higher corporate bond costs, as illustrated by the accompanying exhibit (Exhibit 3), while the cost of corporate bank loans has increased by far less.

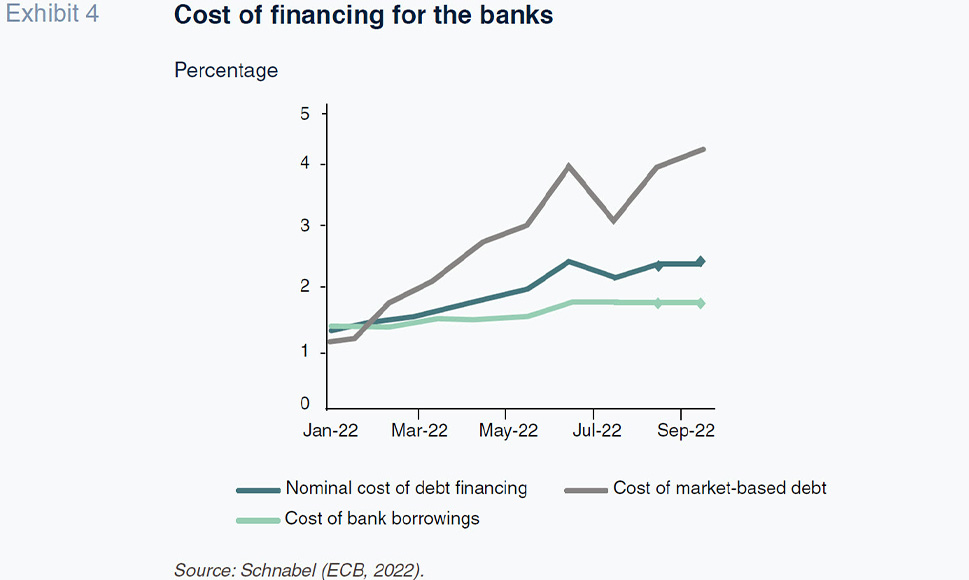

The fact that the cost of bank loans has remained relatively lower, certainly well below the cost of market bonds, is all the more noteworthy considering the fact that the banks themselves have seen the cost of their own market funding rise sharply, indeed by nearly the same magnitude as the cost of corporate bonds, as illustrated in Exhibit 4. The less volatile funding cost associated with bank deposits has enabled the banks to offer their corporate clients loans on terms that have tightened by less than market rates of interest, making bank financing look attractive to the corporate segment.

Lastly, turning to the Spanish experience, the dynamics etched out in the corporate bond and bank financing markets in 2022 lead to similar conclusions in terms of the vulnerability of the capital markets and the presence of the banks as mitigating, back-up mechanisms.

The next exhibits illustrate how activity in the Spanish corporate bond market, which had been registering strong growth since the middle of the last decade, in terms of both issuance volume and number of issuers, totally collapsed in 2022, accompanied by a very sharp increase in average yields on that market to over 4%.

Compared to that rout in capital markets corporate financing, in terms of volume and cost, net corporate bank lending has increased, with greater intensity in the case of the larger companies, clearly hurt disproportionately by the above-mentioned reverse flight to quality triggered by the pronounced crisis sustained by the bond market throughout 2022.

Conclusions

In light of European and Spanish traditional reliance on bank financing compared to the more market-oriented Anglo-Saxon model, policy has focused clearly on increasing reliance on the capital markets, as best embodied by the Capital Markets Union initiative, thanks to which, the weight of market financing has increased considerably (from 10% to 20%) for the European corporates as a whole (by somewhat less in the case of Spain).

Notwithstanding that broad trend, the recent crisis in the bond market, triggered by the spike in inflation and aggravated by the energy crisis and war in Ukraine, has highlighted the vulnerability of that source of financing, whose cost has shot up, sparking an issuance drought. It is precisely during times of capital markets crisis such as these when the complementary back-up or “spare tyre” role of bank financing comes to the fore, as illustrated in this paper, in Spain, Europe and even in the US, the greatest exponent of the market-oriented approach.

References

ALLEN, F., GU, X. and KOWALEWSKI, O. (2017). Financial Structure, Economic Growth and Development. IÉSEG Working Paper Series, 2017-ACF-04.

DARMOUNI, E. and PAPUTSI, M. (European Central Bank, 2022). Europe’s growing league of small corporate bond issuers: New players, different game dynamics. Research Bulletin, No. 96, June 2022.

DEMIRGUC-KUN, A., FEYEN, G. and LEVINE, R. (2012). The Evolving Importance of Banks and Securities Markets. World Bank Economic Review.

ECB (2021). Non-bank financial intermediation in the euro area: implications for monetary policy transmission and key vulnerabilities. Occasional Paper Series, December 2021.

ECB (2022). Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area. April 2022.

SCHNABEL, I. (European Central Bank, 2022). Inflation in the euro area: causes and outlook. Luxembourg, September 2022.

Marta Alberni, Ángel Berges and María Rodríguez. Afi