The coming fiscal adjustment in Europe

Whether or not there is a reform of the rules for European macroeconomic policy coordination, policymakers across Europe will need to begin consolidating their fiscal accounts. The high rate of inflation in the wake of the pandemic has eased some of that adjustment burden, but the swift monetary tightening introduced to calm rapid price increases will add to the challenge.

Abstract: The fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic added significantly to European public debt. This was only to be expected, and in March 2020 the European Commission triggered the ‘general escape clause’ of the Stability and Growth Pact to accommodate the need for greater public spending. That ‘general escape clause’ will be deactivated on 31 December 2023. Whether or not there is a reform of the rules for European macroeconomic policy coordination, policymakers across Europe will need to begin consolidating their fiscal accounts in preparation. Such efforts will be particularly important for the six European Union (EU) member states with public debt worth more than 100 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). The high rate of inflation in the wake of the pandemic has eased some of that adjustment burden, but the swift monetary tightening introduced to calm rapid price increases will add to the challenge.

Introduction

One of the great lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic is about the importance of fiscal policy. Governments need to be able to spend money to offset powerful economic shocks. And, when those governments spend money effectively, they can do a lot to lessen the impact of such shocks on the economy and on society. This lesson does not deny the importance of maintaining sustainable public debts. There is a healthy debate in macroeconomics about the importance of government borrowing and the usefulness of discretionary fiscal policy in fine-tuning macroeconomic performance, but there is broad agreement at the extremes of the argument. [1] Governments need to be able to spend money in times of crisis; and they need to be able to consolidate their finances again once that crisis has passed.

The fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic was impressive. The ratio of public debt to gross domestic product (GDP) across the euro area was 86 percent in 2019 and 97 percent in 2021.

[2] The effectiveness of that response was impressive as well. Although nominal GDP contracted at the height of the pandemic, it quickly expanded again once governments were able to vaccinate their populations and relax constraints on freedom of movement. Unemployment across the euro area increased, but only temporarily and soon fell to record lows. The same is true for bankruptcies, which surged initially due to the shutdown of economic activity and the disruption of supply chains, but which nevertheless remained under control. In this sense, the economic disruption caused by the pandemic (and the policy measures introduced to protect national populations) passed much more quickly than it had during the global economic and financial crisis or the European sovereign debt crisis that followed.

Now the focus is shifting from fiscal stimulus to fiscal consolidation. Two debates have emerged within that context. One is about the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination, and the other is about the scale of the challenges that national governments will have to face – particularly in those six countries that have the largest outstanding public debts. The purpose of this article is to focus on those challenges. The broad outlines of the debate over the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination are well-established (Jones, 2021). The European Commission has made specific recommendations.

[3] Those recommendations are based in large measure on joint contributions made by the Spanish and Dutch governments.

[4] But negotiations within the European Council are still underway and the results will be known only later in 2023.

In the meantime, two factors make it important to focus on the magnitude of the challenges to be faced. The first is the decision by the European Council to de-activate the ‘general escape clause’ embedded in the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination at the end of December in 2023. The European Council activated that ‘general escape clause’ in March 2020 in order to give national governments more flexibility in public borrowing so that to bolster the fiscal response to the pandemic. This decision was not a ‘suspension’ of the rules; it was a resort to one of the exceptional circumstances allowed within the rules. Now that the health emergency has passed, there is no longer a strong justification for that clause to remain active (Jones, 2020). As a result, whatever decision the European Council makes about whether or not to reform the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination, it is clear that the state of exception will end and some kind of rules requiring national government to consolidate their public debts will come into effect.

The second factor concerns the sudden acceleration of inflation that took place starting in late 2021 and that gathered momentum after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine the following February. That burst of inflation forced the European Central Bank (ECB) to move quickly to withdraw the monetary accommodation it provided both through the reversal of more unconventional measures, such as large-scale asset purchases and negative interest rates, and through the more straightforward process of raising monetary policy interest rates (Jones, 2023).

That process of monetary tightening started in earnest in March 2022 and culminated in September 2023 as the Governing Council appeared to bring its interest rate adjustments to an end after raising the rate paid on deposits at the ECB to 4 percent. ECB President Christine Lagarde made it clear in her opening statement that ‘the key ECB interest rates have reached levels that, maintained for a sufficiently long duration, will make a substantial contribution to the timely return of inflation to [its policy] target.’

[5] Financial market participants immediately began betting on when that ‘sufficiently long duration’ would come to an end and interest rates would come back down again. For national treasuries, however, the implication was that borrowing costs would not only rise again – in line with the ECB’s most recent adjustment – but also remain high for the foreseeable future.

Relative magnitudes

To understand the scale of the challenge, it is useful to start with the reference values embedded in the European rules for macroeconomic policy coordination. These values point to public debts and deficits relative to GDP at market prices (or ‘nominal’ GDP). They were first introduced in the Treaty on European Union negotiated in 1991 and signed in 1992 in Maastricht as a protocol indicating that countries could qualify for participation in the single currency only if their deficits were at, below, or declining toward 3 percent of GDP at a sufficient rate, and if their debts were at, below, or declining toward 60 percent of GDP at a sufficient rate. [6]

These numbers constituted a single ‘convergence indicator’ – for ‘excessive deficits’ – insofar as accounting standards at the time varied considerably across countries and yet if you assume that nominal GDP grows at roughly 5 percent per annum –which was close to the historical average for the Cold War period– then a government that runs a deficit worth 3 percent of nominal GDP should wind up with an outstanding stock of public debt worth 60 percent of GDP (De Grauwe, 2007). Hence, if the two measures are moving consistently around those numbers, and nominal GDP growth is close to 5 percent, then together they constitute a reasonably good (if rough and ready) indicator for sustainable public finances.

The justification for these reference values has changed over time as countries adopted the euro as a common currency and governments began to worry more about fiscal stability within the monetary union than about qualification for membership. The numbers also became disconnected as nominal GDP growth rates fell below 5 percent across Europe, with the implication being that even a small deficit (relative to GDP) could result in the accumulation of a higher stock of debt (again, relative to GDP). More important, the focus for attention moved from deficits to debts during the European sovereign debt crisis because the problem euro area governments faced was more closely connected to longer-term debt sustainability than to the shorter-term balance between revenue and expenditure.

Despite these changes, however, the focus for policy attention has remained on the ratio of deficits and debts relative to nominal GDP and the numbers 3 and 60 have been reproduced as reference values both in the secondary legislation that sets out the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination – often referred to collectively as the Stability and Growth Pact – and the revised treaty for the European Stability Mechanism.

[7] Therefore, neither the ratio nor the reference values are likely to change whatever happens in the debate about the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination. Instead, the main questions are about how quickly national governments should correct any deviation from the reference values and how much flexibility those governments (and hence also the European Commission) should have in designing and implementing any fiscal adjustment programme.

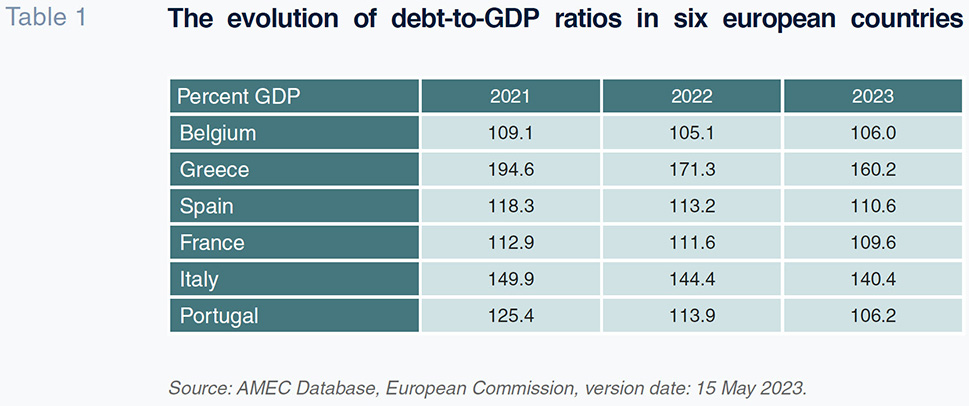

Those adjustment programmes are likely to be significant if they are to close the gap between existing debts and the 60 percent reference value. As the data in Table 1 reveal, six countries in the euro area have debts in excess of 100 percent of GDP. According to the latest estimates for 2023, the range runs from Greece, with a stock of debt worth 160 percent of GDP, to Belgium and Portugal, which have outstanding debt stocks worth around 106 percent. Of course, these ratios can change quickly. Greece’s debt fell to that level from almost 195 percent of GDP in 2021 and Portugal’s debt fell from more than 125 percent. These are changes in the respective ratios of 19.5 percent and 16.6 percent, respectively. But the ratios can also move slowly. Belgium started in 2021 with debt worth 109 percent, and its stock of debt relative to GDP fell by only 2.9 percent over the same two-year period.

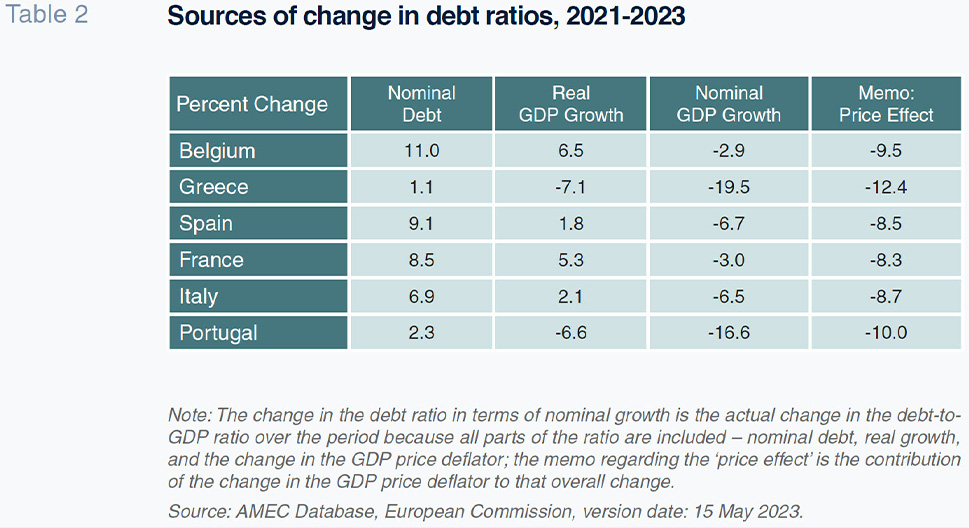

These relative movements can be understood only by unpacking the ratios into different components reflecting the change in the actual amount of national public debt outstanding, the underlying real growth in the national economy (meaning ‘real’ as opposed to ‘nominal’ GDP), and the effect of inflation as captured by the GDP price deflator. This decomposition can be found in Table 2, which shows the cumulative impact of the change in the nominal debt stock as reduced by the growth of real output and then also by the rise in nominal prices. Once all three elements are put together, it is possible to see the actual percentage change in the ratio of debt to GDP. The stand-alone influence of prices is produced as a separate column.

This data makes it easy to explain how Greece was able to make such a large improvement in its outstanding public debt-to-GDP ratio. To begin with, the Greek government added very little to existing debt, which grew by just 1.1 percent over the period from 2021 to 2023. By contrast, the country’s real GDP increased by 8.2 percent over the same period, reducing the ratio of debt to real GDP by 7.1 percent. Price inflation reduced the ratio by another 12.4 percent, which is how the cumulative change wound up at 19.5 percent. It is also easy to explain the contrast between Belgium and Portugal. While Belgium added significantly to its nominal debt stock over the two-year period, Portugal did not. Over the same period, the Belgian economy grew by relatively less in real terms – 4.5 percent versus 8.9 percent in Portugal. Hence while both countries experienced very similar bouts of inflation, Portugal made significantly better headway in lowering its debt-to-GDP ratio.

This kind of analysis is useful to highlight different sources of concern. For example, Italy, France, and Spain added significantly to their outstanding stock of debt over the 2021-2023 period. That increase in outstanding debt has been obscured by impressive real GDP growth in Spain and by significant price inflation in all three countries. The question is whether such favourable macroeconomic performance is likely to continue. Given the efforts by the ECB to reduce inflation even if at the expense of real GDP growth, it is more likely that both elements in the denominator of the debt-to-GDP ratio will grow more slowly in the years ahead. Therefore, it will be necessary to slow the growth in the stock of nominal debt to maintain any reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio. This is not an argument in favour of austerity. It is simply a reflection of how relative magnitudes evolve.

Inflation and interest rates

There are other ways that a higher rate of real GDP growth and fast price inflation support debt stabilization. Higher GDP growth translates into more tax revenues and – through higher employment and rising incomes – lower benefit payouts. Fast price inflation boosts tax revenue as well, both by pushing taxpayers into higher brackets and through the proportional yield on indirect taxes. Of course, governments also have to pay higher prices for goods and services, but that change in the cost base operates only on part of overall government expenditure and with a lag. A slowdown in real GDP growth and a deceleration of price inflation has the opposite effect – lowering tax revenues and, with a lag, raising benefit payouts. These ‘automatic stabilizers’ are a necessary part of fiscal planning. That is why the European rules for macroeconomic policy coordination focus attention on ‘structural’ indicators that give less weight to any deviation from longer-term trends in macroeconomic performance.

The more serious challenge comes from the potential impact of monetary tightening on the cost of government borrowing. That impact can be felt quickly in terms of the yield on short-term government debt, which turns over regularly and so adapts to any change in monetary policy. The impact of monetary tightening passes through much more slowly into the cost of longer-term borrowing. The longer the average maturity of the debt, the smaller the share that will need to be refinanced at higher interest rates. And average maturities tend to be very long in the euro area. Greece benefits from very long maturities – averaging 20 years – due to the financing strategy that government pursued during the sovereign debt crisis. Spain and Portugal have an average maturity of roughly 8 years; Italy is closer to 7. This means that the pass through of higher borrowing into government finances will take a long time to have an impact (Claeys and Guetta-Jeanrenaud, 2022).

Nevertheless, those debt instruments that do roll over during a period of high interest rates will have an impact on government finances for a long time. Therefore, the issue is not just the extent to which interest rates increase but also the amount of time they remain high. This is where the ECB’s determination to hold interest rates at their current level ‘for a sufficiently long duration’ becomes important, because – as the ECB itself has cautioned – a prolonged period of relatively high interest rates could ‘further increase the debt burden and potentially heighten overall vulnerabilities’ in the markets for ‘higher-debt countries’ (Bouabdallah et al., 2021).

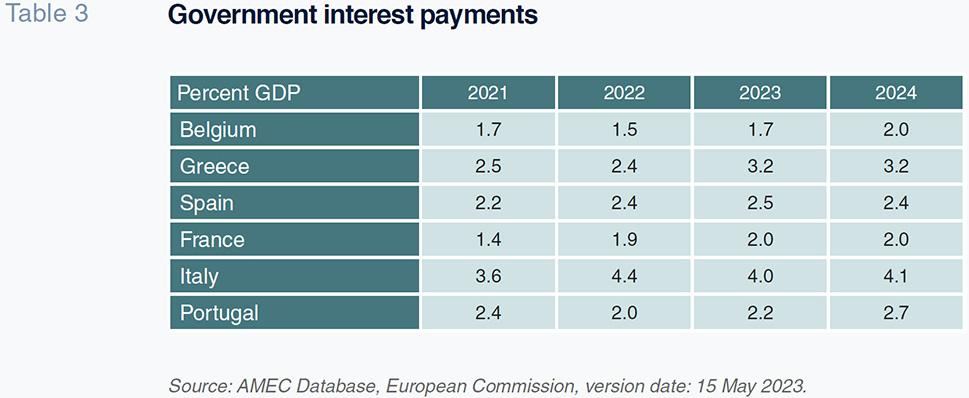

This ECB analysis was done already in 2021 and anticipated both the impact of acerating growth and higher inflation on existing debt-to-GDP ratios and the potential for higher interest rates to push in the opposite direction. So far, the evidence for that increasing friction has yet to appear. As Table 3 reveals, data for government interest payments does not show a clear trend across countries for the period from 2021 to 2023. Nevertheless, the forecast made by the European Commission in May 2023 is that – except for Spain – interest payments will remain the same or increase in 2024. Since these forecasts were made before the ECB completed its cycle of tightening policy rates, it is possible to imagine that the October 2023 revisions to this data will show an even larger impact.

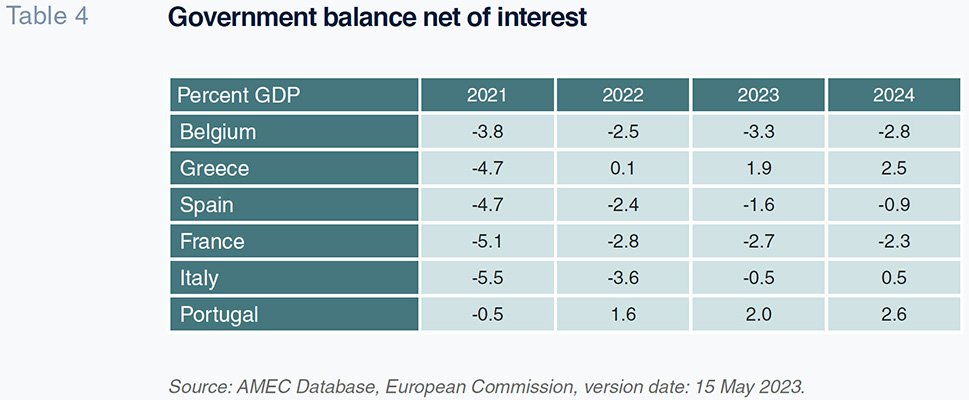

The solution is for governments to raise more revenues than the need for expenditures net of the funds required to service the public debt as a means of compensating for the effects of slower nominal growth and higher interest rates. Such effort is likely to go beyond slowing down the growth in nominal new debt – particularly for those countries currently running significant deficits on their government balances net of interest. This data can be found in Table 4. Again, the forecasts for 2024 were made in May 2023 and so may be revised downward (making the situation worse, not better) in October.

According to this data, Belgium and France have significant deficits compared to other countries. That variation may be a reflection of the fact that those countries also pay less in terms of interest (Table 3) because they face lower borrowing costs in the market. France pays 120 basis points (or 1.2 percentage points) less than Italy on its ten-year sovereign debt, for example. The spread between Belgium and Italy is 114 basis points (or 1.14 percentage points). Even such favourable borrowing costs, however, cannot undue the underlying arithmetic. If the governments of France and Belgium need to stabilize or improve their debt-to-GDP ratios in the face of rising borrowing costs and slowing nominal growth rates, they will need to tighten their government balances net of interest.

Fiscal adjustment

The conclusion is that the six most heavily indebted countries in the euro area will inevitably face a fiscal adjustment. Such adjustment will be necessary whatever the European Council agrees to be the rules for macroeconomic policy coordination. So long as the policy target remains framed in terms of a ratio of public debt or fiscal deficits to gross domestic product with reference values fixed at 60 percent and 3 percent respectively, an outstanding stock of public debt worth over 100 percent of GDP will need to be corrected. Moreover, that correction will not be automatic. Although fast nominal output growth has strengthened government balances, the positive effect of higher growth and faster price inflation is weakening as the European Central Bank tightens its monetary policy instruments in an effort to restore price stability. This monetary tightening will not only reduce those elements that lower the debt ratio but will also raise the cost of borrowing and so create additional expenditures. Hence, governments will need to strengthen their efforts at fiscal adjustment.

Importantly, this analysis leaves out many of the crucial elements for political discretion. The timing and composition of any fiscal adjustment is a political decision; so is the choice to remain within a rules-based framework for macroeconomic policy coordination. These choices are influenced by other lessons learned about the active use of fiscal policy. The COVID-19 pandemic reminded us that having a fiscal policy is important to offset powerful economic shocks. That is now a point of consensus. The gradual normalization of macroeconomic conditions after the pandemic, however, means we also return to the debate about the usefulness of discretionary fiscal policy in fine-tuning macroeconomic performance.

Notes

For an example of the debate over fiscal policy, see Barry Eichengreen et al. (2021).

The data for 2020 are not as useful for comparison with the pre-pandemic period as the data for 2021 because the economic lockdowns used to protect society from the spread of the virus compressed gross domestic product and so inflated the debt ratio; once the lockdowns were largely removed in 2021, economic activity quickly returned to something closer to normal.

The European Commission’s proposals were published on 26 April 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_2393

See, for example: “Joint Paper by Spain and The Netherlands on Priority Issues in 2022 on the EU’s Economic and Financial Policy Agenda”(April 2022. https://www.government.nl/latest/news/2022/04/04/spain-and-the-netherlands-call-for-a-renewed-eu-fiscal-framework-fit-for-current-and-future-challenges).

This statement is repeated (for emphasis) in the introduction and conclusion of the opening statement made at the press conference on 14 September 2023. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2023/html/ecb.is230914~686786984a.en.html

See “Protocol (No 12) on the Excessive Deficit Procedure” in the Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union (as signed at Maastricht). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eut/teu/attachment/13

Again, see Jones, “The Coming Debate about European Macroeconomic Policy.”

References

BOUABDALLAH, O., CHECHERITA-WESTPAHL, C., DE VETTE, N. and GARDÓ, S. (2021). Sensistivity of Sovereign Debt in the Euro Area to an Interest Rate-Growth Differential Shock, box prepared for the November 2021.

Financial Stability Review.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/

pub/financial-stability/fsr/focus/2021/html/ecb.fsrbox202111_01~f37aaca9fb.en.htmlCLAEYS, G. and GUETTA-JEANRENAUD, L. (2022). How Rate Increases Could Impact on Debt Ratios in the Euro Area’s Most Indebted Countries. Bruegel Blog Post (5 July 2022).

https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/how-rate-increases-could-impact-debt-ratios-

euro-areas-most-indebted-countriesEICHENGREEN, B., EL-GANANY, A., ESTEVES, R. and MITCHENER, K. J. (2021).

In Defense of Public Debt. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

JONES, E. (2020).

When and How to Deactivate the SGP General Escape Clause. Brussels: Economic Governance Support Unit, Directorate General for Internal Policies, European Parliament, PE 651.378, November 2020.

JONES, E. (2021). The Coming Debate about European Macroeconomic Policy.

SEFO – Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 10(1), pp. 5-19. [Published in Spanish as: El debate que viene sobre la política macroeconómica europea.

Cuadernos de Información Económica, 280 (2021) pp. 33-42.]

JONES, E. (2023). Managing the Risks of Quantitative Tightening in the Euro Area.

SEFO – Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 12(1), pp. 5-13. [Published in Spanish as: La gestion de los riesgos del endurecimiento cuantitativo en la eurozona.

Cuadernos de Información Económica, 292 (2023), pp. 15-23.]

Erik Jones. Director of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute