Higher interest rates, excess liquidity and the ECB’s balance sheet

Although the ultimate price stability target has not changed and overnight interest rates remain the channel for policy transmission to the economy, the ECB’s balance sheet has taken on greater purpose relative to its traditional role as a support instrument for monetary policy. Against this backdrop, with the ECB now embarked on the path of policy “normalisation”, it is timely to assess whether it is possible to return to the way things were before 2007, given that excess liquidity is determined by factors exogenous to monetary policy and can coexist with it indefinitely, even if policy is restrictive, as it is today.

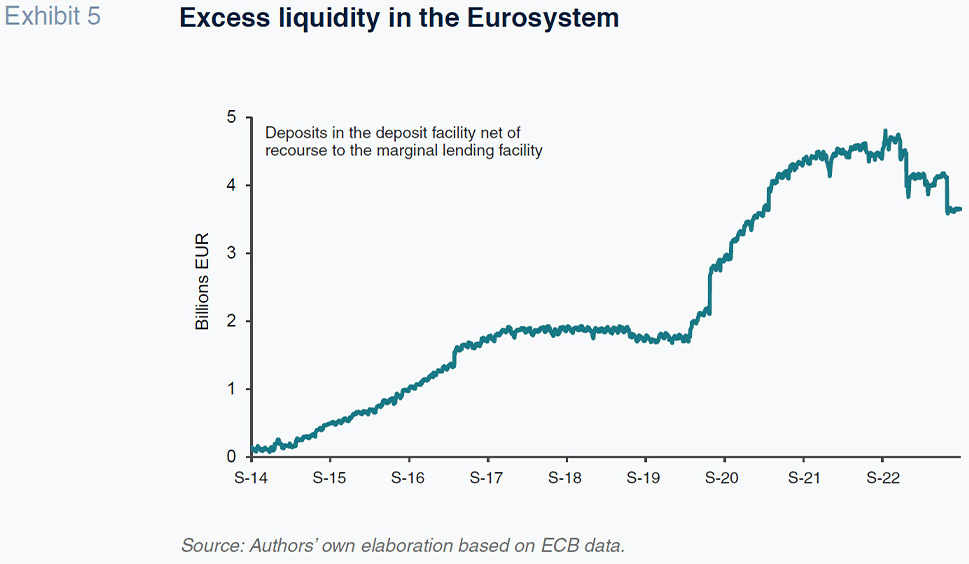

Abstract: Eurozone monetary policy has become far more sophisticated since the onset of the Global Financial Crisis in 2007-2008. Although the ultimate price stability target has not changed and overnight rates remain the channel for policy transmission to the economy, the ECB’s balance sheet has taken on greater purpose relative to its traditional role as a support instrument for monetary policy, entering the field of financial stability and influencing not only overnight rates but also the entire rate curve via new and less orthodox instruments. This situation has led the ECB, along with most of the central banks, to build up a balance sheet of an unprecedented size. Indeed, excess liquidity currently stands at 3.6 trillion euros, compared to 4.8 trillion in September 2022. The situation has sparked controversy, such as that surrounding its remuneration structure; misunderstandings with respect to the importance of quantities in monetary decisions; and unknowns, including questions about the exit strategy and impacts on bond market premiums. Against that backdrop, with the ECB since 2022 on a policy path of “normalisation”, it is timely to ask what that implies and whether it is possible to return to the way things were prior to 2007. Given that excess liquidity is determined by factors exogenous to monetary policy and can coexist with it indefinitely, even if the policy stance is restrictive, as it is now.

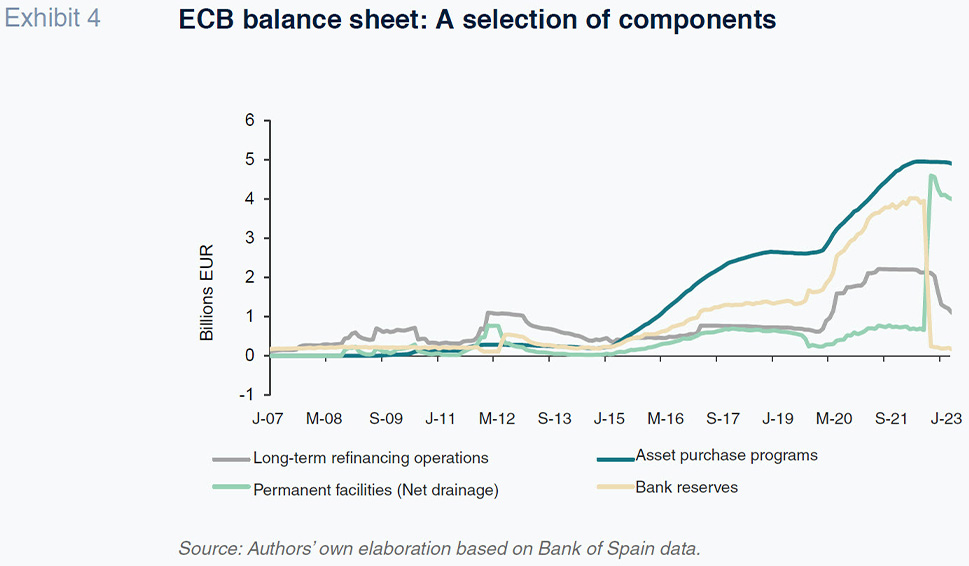

The crisis and the ECB’s balance sheet

In the context of the urgent and exceptional circumstances characterising the financial crisis of 2008, when the normal transmission channels became blocked, the monetary policy toolkit had to be reinvented for two prime reasons: (i) the interbank market had ceased to do its job and needed replacing in order to create stability; and, (ii) with the money and debt markets in a state of shock or dysfunctional, intervention was required in the formation of overnight rates, as well as rates at longer tenors and, once they reached zero, the entire curve.

While implementing its monetary policy, the ECB took up an additional role, acting essentially as intermediary, standing in for the suppliers and demanders of liquidity which had disappeared from an interbank market paralysed by the banking crisis. Replacing the former by taking their funds, which they were no longer lending to the market out of concerns about their counterparties. Replacing the latter because nobody in the market was lending to them on a normal basis. This situation quickly generated significant territorial asymmetry in the TARGET accounts and excess liquidity which the ECB had been draining daily to prevent overnight rates from falling below the levels benchmarked from time to time.

LTROs and other longer-term operations

The ECB’s longest-term operations are structured as main refinancing operations (MROs), i.e., as repos (temporary purchases with a repurchase agreement); they are backed by the same classes of collateral as MROs but provide the banks with liquidity for longer than the week provided by the MROs.

In 2014, the Eurosystem designed other operations with maturities of over three months known as non-regular operations. The use of this facility was triggered by the need to reduce uncertainty around liquidity when the financial crisis broke out. During the years of necessarily highly expansionary policy, these operations had maturities as long as 48 months, as was the case with the so-called targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). The ECB made use of two kinds of facilities in recent years: those designed to tackle the financial crisis and those designed in the wake of the pandemic.

Volume-wise, the TLTROs were the most significant. The TLTROs provided long-term repo financing at a flat rate. At one juncture they were provided for four years and at a cost of zero when the MRO rate was likewise at zero. The idea was to ease lending conditions for the private sector and stimulate bank lending to the real economy (which is why they were dubbed ‘targeted’ operations). In later rounds, TLTRO III and TLTRO II, the interest rate applied was linked to the participating banks’ lending activity.

On 30 April 2020, the ECB announced a new series of seven additional longer term refinancing operations (PELTROs) in order to inject liquidity into the eurozone’s financial system and ensure that the money markets continued to operate smoothly throughout the pandemic. On 10 December 2020, the ECB’s Governing Council decided to offer a series of four further PELTROs in 2021 by way of liquidity back-stop in order to keep the money markets working properly.

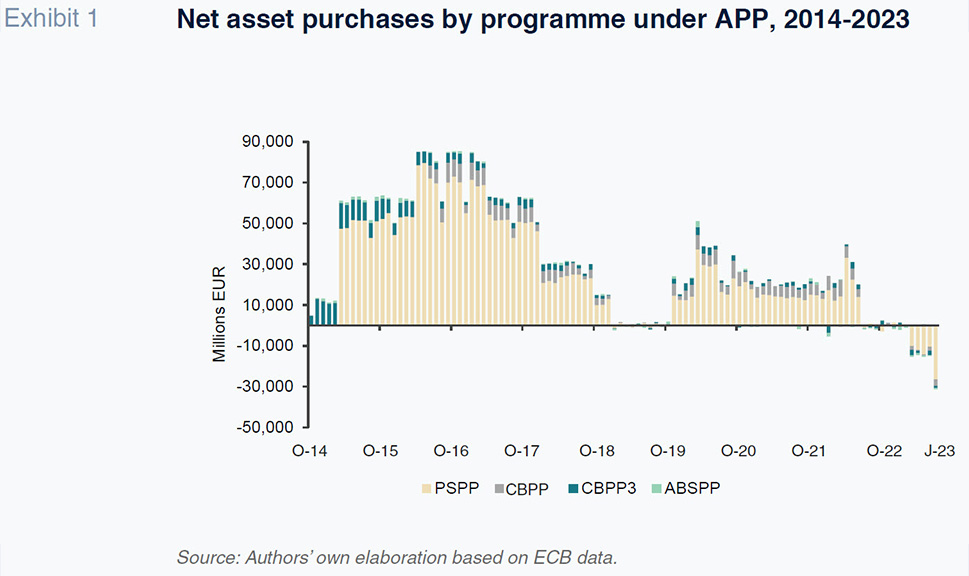

Asset purchases: Trend and breakdown

On 10 May 2010, the central banks of the Eurosystem began to repurchase securities under the scope of the Securities Markets Programme (SMP) in order to address sources of stress and dysfunctions in certain market segments – country asymmetries and fragmentation – which were thought to be impeding monetary policy transmission. Those purchases were the prelude for what would become the asset purchase programmes (APPs). Following Mario Draghi’s decisive “whatever it takes” speech on 6 September 2012, the ECB began to purchase assets directly and did away with the SMP. [1]

The Eurosystem began to purchase securities under the umbrella of its APPs in October 2014. The APP would quickly emerge as the most important unconventional monetary policy measure in quantitative and qualitative terms, with the announced pace of asset purchases becoming a key monetary policy signal.

[2]

Clearly, while the purchases originally came about in response to the complexity caused by the euro crisis of 2012 (SMP), they went on to become key to continuing to fine-tune monetary policy once interest rates bumped up against the zero frontier, preventing the ECB from continuing to directly influence the longer-term interest rate curve (shaping negative real long-term rates).

Unlike the situation facing the Fed in the US, the fact that eurozone countries have different national public debt markets made it vital to have a systematic and objective purchase mechanism capable of neutrally or naturally addressing the existence of different domestic secondary markets.

Chronologically, the APP purchases were structured into the following specific programmes:

- The asset-backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP): from 21 November 2014 to 19 December 2018.

- The third covered bond purchase programme (CBPP3): from 20 October 2014 to 19 December 2018.

- The public sector purchase programme (PSPP): the Eurosystem made net public sector securities purchases under the scope of the PSPP between 9 March 2015 and 19 December 2018. From January to October 2019, the Eurosystem only reinvested the principal repayments from maturing securities held in the PSPP portfolio. Securities purchases under the PSPP recommenced on 1 November 2019 and continued until the end of June 2022.

- The corporate bond purchase programme (CBPP): from 8 June 2016 to 19 December 2018.

Both the purchases and the maturing principal reinvestment policy were articulated around the policy of market neutrality, i.e., they were structured in accordance with the average residual term of each market and its geographic area. To maintain a regular and balanced presence in the market, it was also decided to distribute the reinvestment of maturing principal over time.

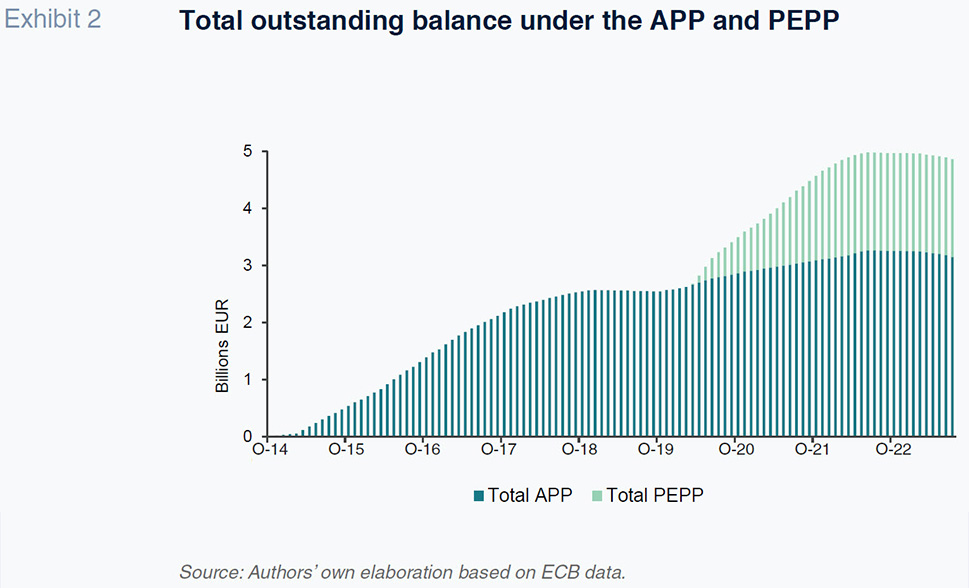

Beyond the various APPs, on 18 March 2020, the ECB announced a 750 billion euro pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), which was increased in size to 1.85 trillion euros in December 2020. That programme was designed in response to the unprecedented circumstances caused by the coronavirus emergency (COVID-19). Net purchases under the PEPP ended in April 2022. Principal repayments from maturing securities acquired under the PEPP are being reinvested in full.

Forward guidance

Forward guidance is the provision of systematic information about future monetary policy intentions, framed by the ECB’s ongoing assessments of prospects for its price stability target.

The ECB began to use forward guidance in July 2013 when its Governing Council said that it expected interest rates to remain “at current or lower levels for an extended period of time”. The ECB continued to provide forward guidance regularly until March 2022.

By keeping the market better informed not only about the immediate actions already decided upon but also its forward-looking intentions, the ECB helped reduce uncertainty while cutting down on the frequency of its interventions.

Normalisation and restrictive level of rates

After 15 years of expansionary monetary policy, in early 2022, the ECB began to normalise its monetary policy. It looked as if we were finally leaving behind a protracted credit and confidence crisis, extended by the onset of the pandemic. The reawakening of inflation, fuelled by the reopening of the economy in the wake of the pandemic, opened the door to ending policy accommodation and, ultimately, embarking on tightening in spring 2023. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, far from curbing demand, only provided new reasons for continuing to roll back the ECB’s highly expansionary positions in light of the effect on energy and many other commodity and food prices. In parallel to increasing its key rates to 4.5% in the case of MROs, the ECB abandoned its forward guidance and devoted itself to managing its large legacy balance sheet.

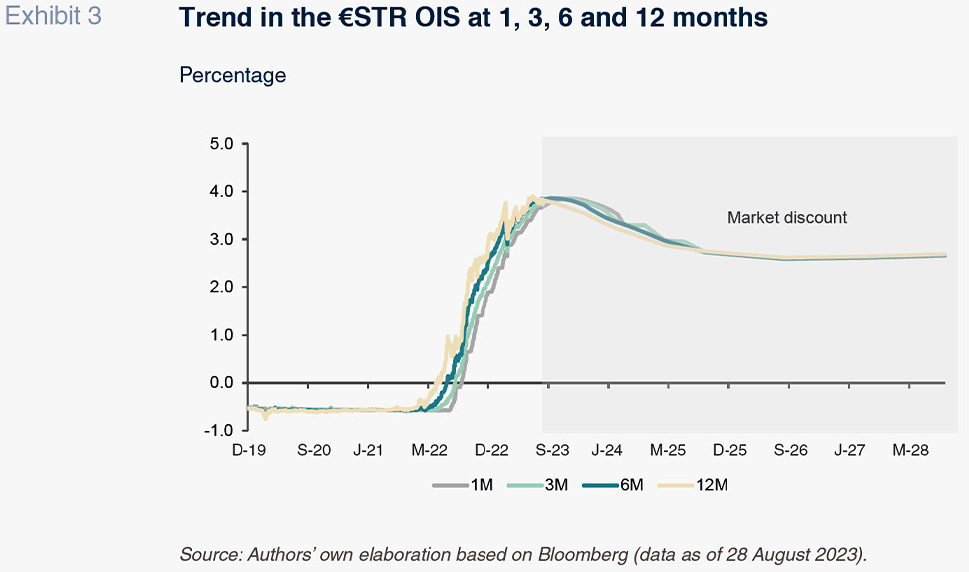

Interest rates reach restrictive levels

2022 started with benchmark euro interest rates at close to zero or in negative territory and with a massive ECB balance sheet – 6.2 trillion euros – with the ECB’s aim, as already noted, of articulating liquidity policy and shaping the entire curve. The latter task meant injecting massive amounts of liquidity into the banks short of reserves and those to whom nobody would lend money while in parallel draining – so sterilising the monetary impact of the volumes injected – the surplus reserves of the banks that were unwilling to lend money.

Shortly after, benchmark rates began to increase. Returning the deposit facility rate (DFR) to zero in July set the plan in motion; from there rates were lifted to a level that could be considered neutral, of 2%, at the Governing Council meeting of December 2022. In our opinion, the MRO rate of 3.75% established on 16 March 2023 (3% for the DFR) marked the start of a key phase in monetary tightening: entry into restrictive territory, with the ECB raising its MRO rate again to 4.5% in August. The current phase is accentuating the slowdown in demand and in the most stubborn components of core inflation.

Balance sheet

As for its balance sheet, the normalisation process has proceeded at a slower pace, as foreshadowed by the ECB itself. Excess liquidity had played a stabilising role beyond monetary policy, making the gradual nature of its withdrawal expected. In March 2022, the ECB decided to eliminate net purchases under the APP and ruled out the introduction of new TLTRO series. In fact, the origin of this excess liquidity is not linked to monetary policy. It is more related to the sluggishness of credit and the accumulation of liquidity positions in companies and families after the 2008 crisis.

Since then, three decisions stand out as regards the reconfiguration of the ECB’s toolkit:

- In September 2022, the ECB reduced remuneration on excess reserves to zero (the lower between the DFR and zero). That prompted the banks to deposit their excess liquidity in the deposit facility, prompting a drop in excess reserves from 3.8 trillion euros at the end of 2021 to a negligible level of around 200 million euros. Symmetrically, use of the deposit facility has increased to around 3.64 trillion euros at present. There was no change in monetary content in the strict sense but the move did reorder the ECB’s balance sheet: the deposit facility resumed its role as the daily drainage tool, at a rate determined exogenously by monetary policy, and the banks started to once again keep their excesses to a minimum to meet their reserve requirement (1% of customer deposits).

- The ECB raised the cost borne by the banks on outstanding TLTROs from November 2022 by setting the rate at the DFR rate (compared to zero), so giving the banks a reason to accelerate their repayments, as is indeed happening.

- On 27 July 2023, the ECB also decided to remunerate the banks’ minimum reserves at zero. Previously, they had been remunerated at the MRO rate, so that this move implied a considerable improvement in the interest borne by the ECB, increasing elbow room around monetary policy now that rates are at significantly higher levels.

As for its asset portfolio, the ECB has taken decisions even more gradually. Initially, it decided not to reinvest all of the principal payments from maturing securities comprising the APP so that the portfolio would decline by 15 billion euros a month until the end of June 2023. Then, having assessed the portfolio down-sizing, the ECB decided to eliminate the reinvestment of those sums from July 2023. Notably, these announcements have had scant impact on the debt markets.

Elsewhere, the ECB plans to reinvest the principal from maturing securities purchased under the scope of the PEPP until at least the end of 2024. Moreover, any future elimination of that portfolio will be managed with a view to avoiding interference with prevailing monetary policy thrust.

Conclusion

Despite the impact of these steps to downsize the ECB’s balance sheet, excess liquidity, and therefore its net withdrawal, will remain in the background of monetary policy in the coming years. Use of the deposit facility, the key monetary policy instrument, stood at 3.64 trillion euros as of July 2023. The bond portfolio amounted to 4.85 trillion euros as of the same date, having declined by close to 100 billion euros in the first seven months of the year. The maturity and prepayment of TLTRO III funds, induced since year-end 2022, has had the effect of reducing their outstanding balance by over 1.5 trillion euros, leaving just 598 billion euros to be repaid as of July 2023.

As a result, excess liquidity currently stands at 3.6 trillion euros, compared to 4.8 trillion in September 2022. The ECB therefore has still a lot of liquidity to drain via the deposit facility. And will for some time. Factoring in the 0.6 trillion euros of TLTRO II funds, caeteris paribus, the system’s position vis-a-vis the ECB will not be rebalanced until the asset portfolio decreases by a further 3 trillion euros. Excess liquidity is determined by factors exogenous to monetary policy and can coexist with it indefinitely, even if its tone is restrictive, as it is now.

In the context of its balance sheet, the system’s excess liquidity gets drained by the ECB – at a DFR whose level reflects once again its monetary policy strategy and not a concession to the banks–.

[3] Given the current benchmark rate structure, if the market’s net position required the ECB to inject rather than to withdraw liquidity, the overnight rate would be guided by the MRO rate (for injecting liquidity) and not by the DFR (for withdrawing it). By way of hypothesis, it is interesting to consider that this situation would imply a 50bp shift relative to the overnight rate (€STR). There is a gap of 50bp between the DFR and MRO rate as a result of the reduction of the latter (from 100bp) when the ECB replaced variable rate tenders for its main refinancing operations with a fixed rate tender procedure with full allotment as far back as October 2008.

Notes

For more information, refer to the press release of 6 September 2012, Technical features of Outright Monetary Transactions; the ECB’s decision of 14 May 2010 (ECB/2010/5), and its press release of 10 May 2010: ECB decides on measures to address severe tensions in financial markets.

The ECB’s Governing Council recalibrated its net purchases regularly.

One of the most widespread misunderstandings around monetary policy tools pertains to the remuneration of minimum reserves.

References

AIRAUDO, F. S. (2023). The role of the fiscal-monetary policy mix. 15 January 2023.

ECB Forum on Central Banking, 26-28 June 2023. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/

pub/conferences/ecbforum/shared/pdf/2023/EFCB_2023_Florencia_Airaudo_Paper.pdfEUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK. (2017). What is excess liquidity and why does it matter? Explainer series, 28 December 2017.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/

educational/explainers/tell-me-more/html/excess_liquidity.en.htmlEUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK. (2023). History of all ECB open market operations.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omo/html/top_history.en.htmlEZQUIAGA, I. and AMOR, J. M. (2023). Euro yield curve evolution and real long-term rates.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Vol. 12, No. 2, March.

https://www.sefofuncas.com//Assessing-the-far-reaching-implications-of-a-rising-Euribor/Euro-yield-curve-evolution-and-real-long-term-ratesVISSING-JøRGENSEN, A. (2023). Macroeconomic stabilisation in a volatile inflation environment. Balance sheet policy above the ELB.

ECB Forum on Central Banking, 26-28 June 2023.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/conferences/ecbforum/shared/pdf/2023/VissingJorgensen_paper.pdf

Ignacio Ezquiaga. Afi

José Manuel Amor. Managing partner at Afi