European and US banks: Inflexion point in their relative performance

After years of US outperformance, last year marked an inflexion point in the relative performances of the European and US banks in terms of both their market values and earnings. The relative outperformance by the European banks went a long way to close the sizeable profitability and valuation gaps opened up between the two systems more than a decade ago.

[1]

Abstract: In the context of extraordinary market volatility, triggered by the war in Ukraine and its consequences in terms of exacerbating the energy crisis and inflationary pressures, we have seen significant shifts in relative valuations across different asset classes and/or sectors, some of which breaking from patterns that had become entrenched for many years. After years of US outperformance, last year marked an inflexion point in the relative performances of the European and US banks in terms of both their market values and earnings, particularly in the second half. The search for a factor that explains the banks’ outperformance relative to other sectors and within the banking sector the European sector’s outperformance relative to that of the US yields one obvious answer: the recent trend in interest rates against the backdrop of monetary policy tightening. The scant sensitivity of the US banks to the increase in dollar rates contrasts sharply with the high correlation observed in Europe and Spain, largely explaining the stock market performances of the European and Spanish banking sectors relative to the remaining sectors and by comparison with the US banks. But there are also structural factors underpinning EU banks’ outperformance. Indeed, the improvement registered in the Spanish and European banks’ ROEs is being driven by a more stable provisioning profile. There is still a profitability and valuation gap between the two systems but the distance has narrowed considerably by comparison with that prevailing systematically for nearly a decade.

[2]

Inflation and interest rates shift market equilibriums

In the context of extraordinary market volatility, triggered by the war in Ukraine and its consequences in terms of exacerbating the energy crisis and inflationary pressures, some of which are proving stubborn, we have seen significant shifts in relative valuations across different asset classes and/or sectors, some of which breaking from patterns that had become entrenched for many years. It is against that backdrop that we have decided to analyse the resurgence of the banks relative to other sectors and the resurgence of Europe (and Spain) relative to the US’ long-standing dominance.

The biggest break from a convention that has held for nearly a decade materialised in the sovereign debt markets. The sharp increases (over 3 percentage points) observed at the long ends of the yield curves in nearly every country generated significant corrections (over 10%) for the main holders of those assets. Among those holders, it is worth highlighting the central banks themselves, which have been sustaining heavy losses on the public debt portfolios accumulated as a result of their various asset purchase programmes (Quantitative Easing) throughout the years of ultra-lax monetary policy now abandoned. At any rate, as the BIS (2023) acknowledges, the losses notched up by the central banks are not relevant and do not tarnish the work done by those institutions to attain the monetary policy objectives framing those purchases in the first place.

The banks are in a similar situation with respect to their public debt holdings. Indeed, we flagged the potential for losses on those investments in an earlier piece for this same publication (refer to Alberni, Berges and Rodríguez (2022)). As we argued in that paper, those losses will only be realised on a small fraction of those portfolios (those held for trading in the near-term), with the bulk held as part of a comprehensive balance sheet management strategy, the effects of which will crystallise together with the other effects associated with the new rate scenario, as we will outline later on.

The public debt markets were not the only markets adversely affected by the crisis. The private fixed income markets have also reeled and with the drop in volumes, their ability to feed financing to numerous companies that had embraced those markets as a preferred source of financing dried up. Cooling in those markets forced companies to resort to bank financing once again, as detailed in our most recent paper (refer to Alberni, Berges and Rodríguez (2023) and later corroborated by the European Central Bank (2023)).

The equity markets have also undergone sea changes, with sector rotations that dispute some of the most entrenched assumptions of the past decade or so. Firstly, for obvious reasons, it is worth highlighting the reawakening of the sectors benefitting most directly from the energy and commodity crisis, borne out in significant rallies across the sector players and revaluations of the currencies of the countries –mostly emerging markets– more exposed to those sectors.

However, the most remarkable development has been the loss of appetite for the technology sector, which has been the star performer for a decade, as gleaned from the gain notched up by its most representative index, Nasdaq, of over 30%.

The European banks have taken the baton from their US counterparts as a result of sector and geographical rotation

Those changes, especially the technology sector’s loss of lustre after a decade in the spotlight, coincided with the rally in bank stocks, especially the European banks, which spearheaded the rally underway since the second half of 2022.

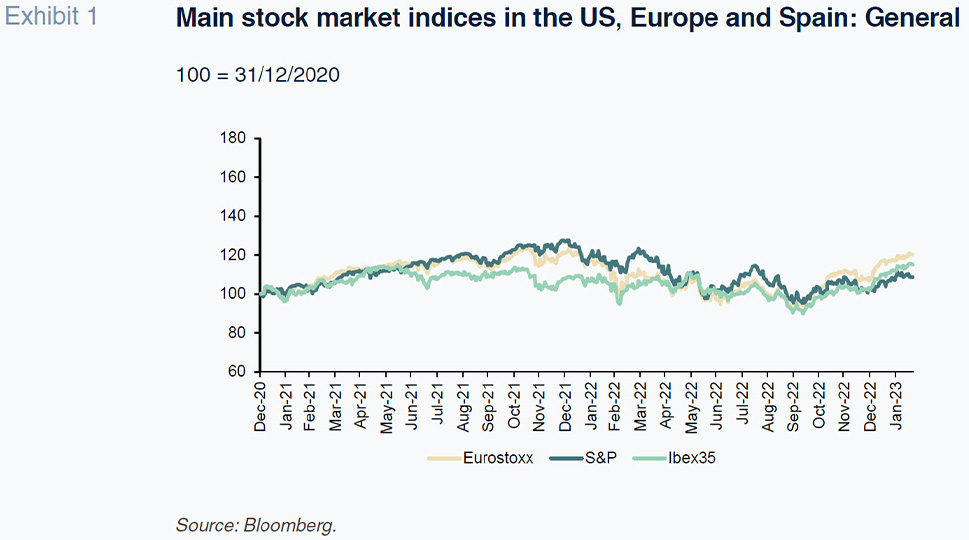

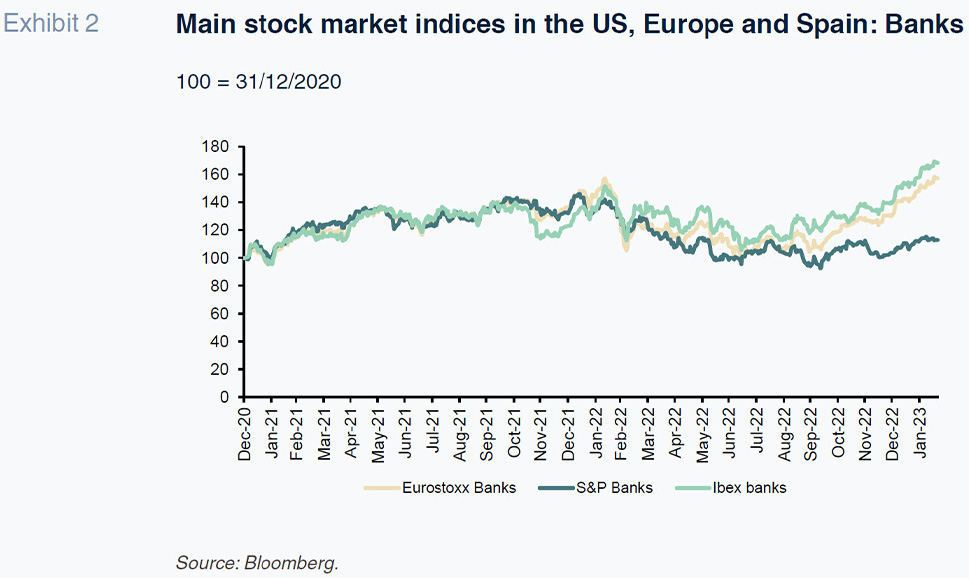

Exhibits 1 and 2, which illustrate the performance of the main stock market indices in the US (S&P), Europe (Eurostoxx) and Spain (Ibex), on aggregate (Exhibit 1) and for their banking sectors (Exhibit 2), speak volumes about the scale of the revaluation of the banks relative to the other traded sectors, especially in Europe and Spain.

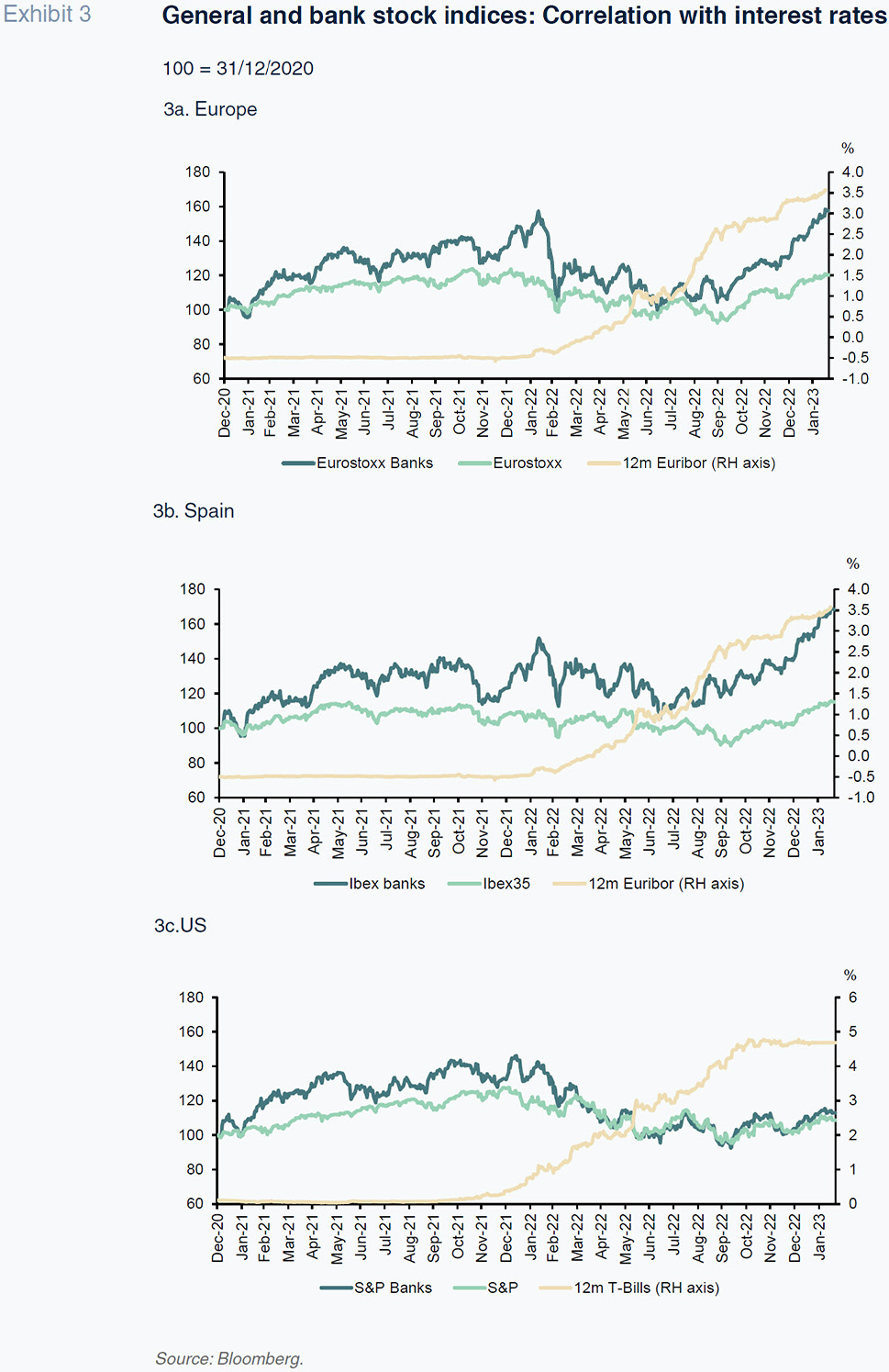

The search for a factor that explains the banks’ outperformance relative to other sectors and within the banking sector the European sector’s outperformance relative to that of the US yields one obvious answer: the recent trend in interest rates against the backdrop of monetary policy tightening.

That thesis is sufficiently borne out in Exhibits 3a, 3b and 3c, which map, for each of the three regions analysed (Europe, Spain, and the US), their general and banking stock indices against the benchmark rate of greatest relevance for their banking industries, namely 12-month Euribor in Europe and Spain and 12-month T-Bills in the US. The scant sensitivity of the US banks to the increase in dollar rates contrasts sharply with the high correlation observed in Europe and Spain, largely explaining the stock market performances of the European and Spanish banking sectors relative to the remaining sectors and by comparison with the US banks.

The European and Spanish banks’ outperformance has put their market valuations back at the levels observed prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which is not the case in the US. As a result, the valuations of the banks on either side of the Atlantic have converged somewhat. However, the US banks still fetch a premium. The European and Spanish banks presented weighted average price-to-book (P/B) ratios of 0.69 and 0.72, respectively, at year-end 2022. The good news is that those levels are well above those of recent years and indeed higher than at nearly any time since the financial crisis of 2010-2012.

However, the banks’ multiple rerating does not mask the fact that those ratios are still considerably below 1x and below the US banks’ valuations which, despite a meeker stock market performance last year, ended 2022 with an average P/B ratio of 1.3x, albeit well below the 1.6x recorded in 2021, which was a record year for the American banks.

Structural elements of outperformance

Having taken stock of the clearcut inflexion point in the European banks’ valuations relative to their US counterparts, the next step is to analyse the trend in the main business metrics on both sides of the Atlantic in an attempt to determine whether the convergence has been structurally driven.

In the past, the valuation premium commanded by the US banks relative to their European peers stemmed from their ability to generate a much higher return on equity (ROE). To that end we will centre our analysis on that metric in order to detect whether there has also been a profitability tide change in favour of the European banks and, if so, whether it is likely to prove structural or transient.

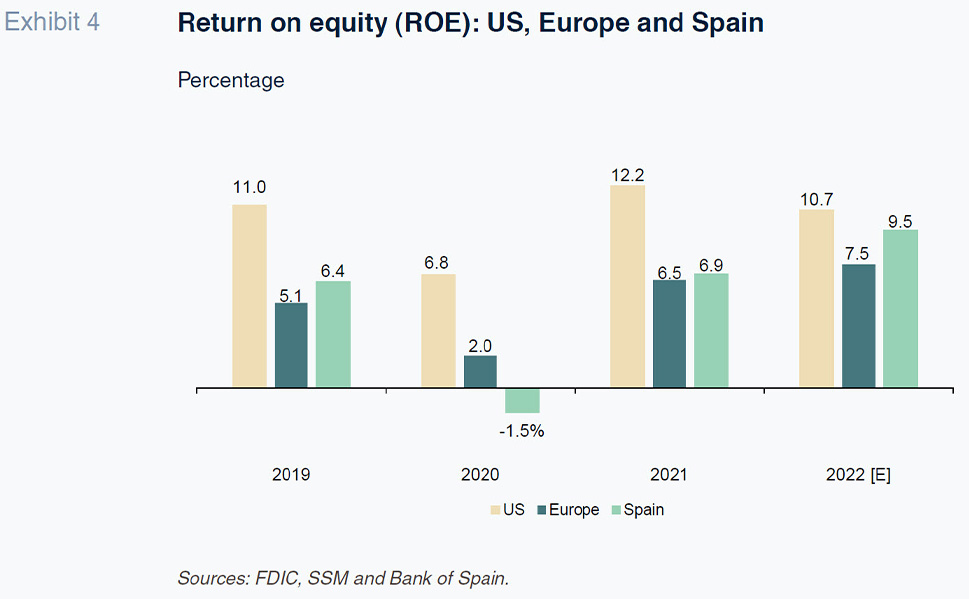

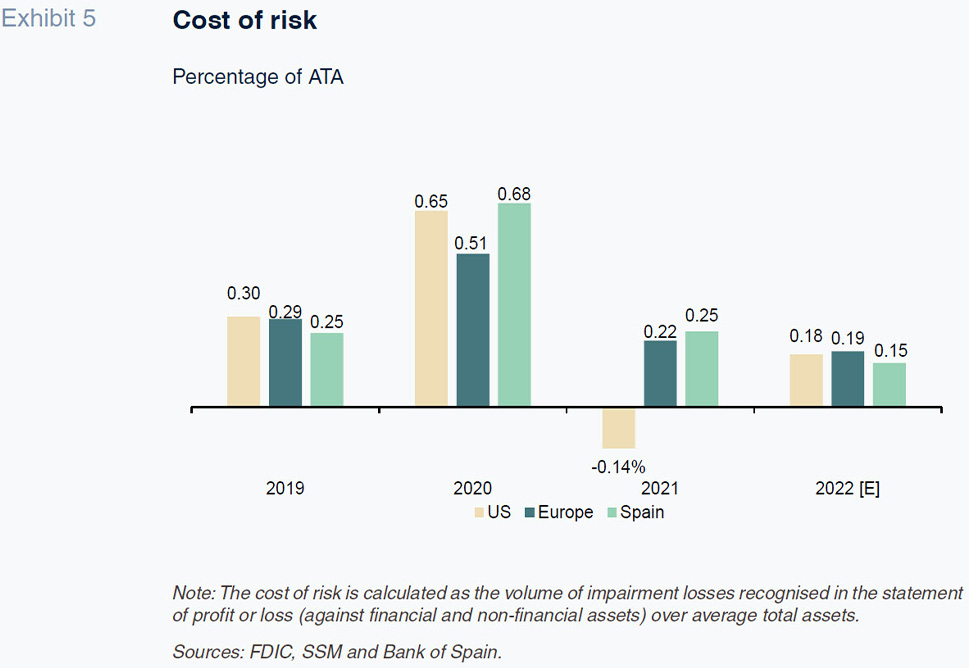

Although only a few banks have reported their 2022 earnings, Exhibit 4 estimates the weighted average ROEs for the year for each of the regions analysed, comparing them with three milestone years: 2019, a proxy for the pre-pandemic business; 2020, a year of extraordinary adjustments and provisions; and 2021, the year of recovery from those provisions.

Beyond the clearcut trend of convergence between Europe and the US, what jumps out is the different lengths of time taken for ROE to bounce back after the sharp contraction induced by the pandemic in both regions. In the wake of that shock, the European and Spanish banks have recorded a sustained strong recovery, while the US banks have been more volatile, experiencing a pronounced increase in returns in 2021, followed by a dip in 2022.

Indeed, the correct reading of the numbers is not so much that the US banks posted a low return in 2022, although aggregate profits fell by close to 10%, but rather that the high return achieved in 2021 was unsustainable. We arrive at that conclusion by analysing the banks’ impairment provisions in 2021. That year, the US banks reversed a significant percentage of the loan-loss provisions recognised in 2020 in the midst of the pandemic, recognising them as a gain in their statements of profit or loss in 2021.

The reversal of those provisions in 2021 and the attendant reduction of the buffer set aside during the worst year of the pandemic obliged the US banks to recognise new provisions in 2022, triggered by uncertainty about the economic cycle, the US banks’ riskier profiles and the toll taken by the adverse performance of the capital markets on their investment banking business.

Compared to the US banks’ more volatile profile, making the most of their surplus provisions in the good years, like 2021, only to be forced to recognise new provisions in years of heightened uncertainty (2022), the European and Spanish banks present a more conservative profile characterised by relative stability in terms of the volume of provisions recognised and released through profit and loss. In 2021, the European banks did not reverse the heavy provisions recognised in 2020 in conjunction with the pandemic, enabling them to reach cruising speed in 2022 without having to record new provisions against their earnings that year.

Thanks to that strategy, the European banks have been able to fully capitalise on the favourable effect of the new interest rate scenario on their net interest margin. The latter metric is registering double-digit growth in the US, Europe and Spain alike but, unlike in Europe, in the US, the adverse effect of the new provisioning effort in the US has fully wiped out the bump in margin.

In other words, the improvement registered in the Spanish and European banks’ ROEs is being driven by structural factors which substantiate the inflexion in their valuations relative to the American counterparts. There is still a profitability and valuation gap between the two systems but the distance has narrowed considerably by comparison with that prevailing systematically for nearly a decade.

Notes

This article was written prior to the events that have taken place in the US and Swiss banking sectors, which brought about adverse effects for global banks, but in particular for US regional banks.

All of the analyses contained in this article refer to financial developments in 2022 and stock market valuations up to mid-February. Valuations have been greatly affected by events at some regional American banks and a large Swiss bank.

References

ALBERNI, M., BERGES, Á. and RODRÍGUEZ, M. (2022). The yield curve and the bank-public debt nexus.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook (SEFO), Volume 11, No. 4, July 2022.

https://www.funcas.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/4-Alberni-11-4.pdfALBERNI, M., BERGES, Á. and RODRÍGUEZ, M. (2023). Corporate finance: Banks

versus capital markets.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook (SEFO), Volume 12, No. 1, January.

https://www.sefofuncas.com//Perspectives-for-the-global-and-Spanish-economy-in-2023/Corporate-finance-Banks-versus-capital-marketsBANK OF INTERNATIONAL SETLEMENTS. (2023). Why are central banks reporting losses? Does it matter?

BIS Bulletin, No. 68, February 2023.

BCE (2023). Substitution between debt security issuance and bank loans: evidence from the SAFE.

ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 1 /2023.

Marta Alberni, Ángel Berges and María Rodríguez. Afi