Securing fiscal stability in the context of uncertainty

Decisive policy action in response to the pandemic at the EU and Spanish level has been more effective than measures taken to tackle the Great Recession; yet, recent support measures have clouded the outlook for fiscal stability. Ensuring compliance with the European fiscal rules and securing a path towards debt sustainability in the future will require defining today the reforms and targets needed to realign public revenue with expenditure.

Abstract: Decisive policy actions in response to the pandemic at the EU and Spanish level have been more effective than those taken to tackle the Great Recession. However, those same decisions have also clouded the outlook for fiscal stability. Transitory relief is drawing to an end at a time when interest rates are increasing, and the adverse effects of uncertainty will weigh on GDP growth and its trajectory back to pre-pandemic levels. In the first half of the year, the overall deficit has come down sharply to already below the target of 5% for 2022, compared to 6.8% in 2021, although the forecasts for this year are not entirely aligned. The positive and unexpected dynamics of tax collection are the reason why the increase in public spending is not having a significantly adverse impact on the deficit. Assuming no change in policy, the government expects the deficit to gradually trend down towards around 3% in 2025, shaped by a structural deficit which, despite a slight improvement, would remain above 3%. Moreover, while the government is forecasting a very slow but steady reduction in the debt ratio, the Bank of Spain sees no prospect for improvement. Within this context, it is not enough to hope for correction via the economic situation, which looks likely to be more complex in 2023 than was anticipated a few months ago. To ensure compliance with the incoming European fiscal rules and the eligibility criteria for the new Transmission Protection Instrument, limit the country’s debt service burden in the medium-term and win back space for discretionary fiscal policy, now is the time to define reforms and targets to realign public revenue with expenditure.

Introduction

Spain and indeed the whole of the European Union are reeling from a host of intense and unexpected negative shocks. These shocks have been triggered by factors that are exogenous to the economic system but are having a sharp and swift impact thereon. In general, the responses devised at both the European and Spanish level have been astute and rightly focused. Without question, they have been more effective and forceful than those taken to tackle the Great Recession. However, those same reactions have also clouded the horizon as far as fiscal stability is concerned.

Spain’s public accounts are a clear example. The collapse in tax collection and increase in public spending needed to offset the health and economic consequences of the pandemic pushed the public deficit above 10% of gross domestic product (GDP) and the public debt ratio to over 125% of GDP. Both fiscal metrics, despite improving in 2021 and so far in 2022, have remained significantly above benchmark levels by European Union standards. Those high levels have not posed a bigger issue for the country’s financial stability thanks to activation of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) escape clause and the European Central Bank’s extraordinary bond purchase programme.

That transitory relief is drawing to an end: the extraordinary bond repurchase programme is being rolled back and will be replaced by a monetary policy Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), state eligibility for which will imply compliance with certain criteria; the cost at which public debt gets issued is set to rise gradually; and, the EU fiscal rules will be reinstated, as amended, in 2024 (Lago Peñas, 2022). Moreover, the return to a less expansionary fiscal policy is set to take place against the backdrop of a macroeconomic climate which has deteriorated sharply in recent months as a result, mainly, of the war in Ukraine. Specifically, we are looking at an increase in inflation rates that is not acceptable by European standards, so forcing an abrupt shift in monetary policy. The increase in interest rates, coupled with the difficulty in securing a broad income pact, and the adverse effect of the prevailing uncertainty on consumer and investment decisions, will weigh on GDP growth and its trajectory back to pre-pandemic levels.

The objectives of this paper are threefold. Firstly, to assess the budget outturn so far in 2022 and the outlook for the rest of the year. Secondly, to look at the projections for 2023 to 2025, based on public information about the government’s plans and commitments as they relate to either side of the budget equation. And thirdly, to provide an overview of certain key matters for defining and implementing a robust fiscal consolidation strategy in Spain.

Budget outturn year-to-date and outlook for the rest of 2022

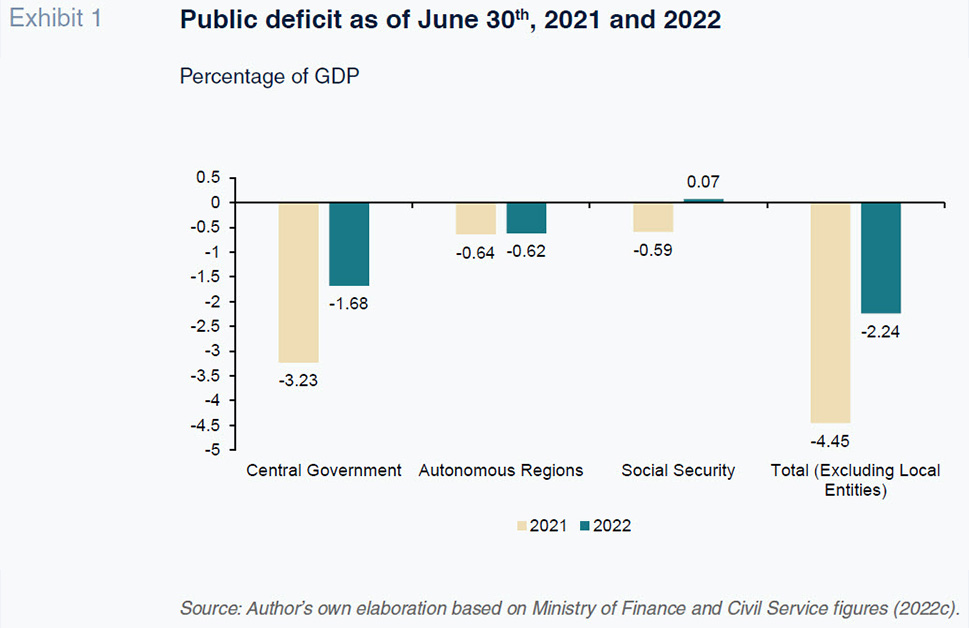

Exhibit 1 provides the budget outturn up until June 30th, 2022, and compares it to that corresponding to the same period of 2021. The figures are expressed as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) and exclude local governments. According to Spain’s independent fiscal institute, AIReF (2022b), local governments are expected to present a surplus of 0.2% of GDP this year, just below that of 0.27% attained in 2021. The overall deficit has come down sharply in the first six months of the year (by 2.2 percentage points), already dipping below the target for the full year, namely that of reaching 5%, compared to 6.8% in 2021.

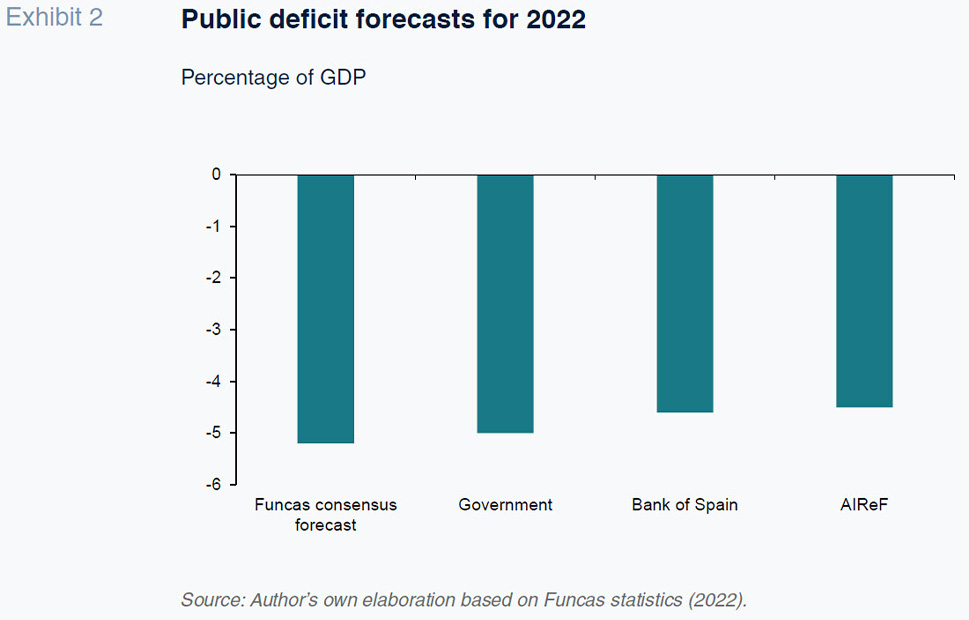

The forecasts for 2022, as shown in Exhibit 2, are not entirely aligned. Whereas the Funcas consensus forecast is for a deficit of 5.2%, 0.2 percentage points above the official target of 5.0%, the Bank of Spain (4.6%) and AIReF (4.5%) are a lot more upbeat, assuming consolidation of the dynamics observed during the first half of the year, despite factoring in the budgetary cost of many of the compensatory measures taken to tackle the fallout from the invasion of Ukraine. According to AIReF (Herrero, 2022), the measures already passed by the end of June will imply a cost of 13.06 billion euros, which is roughly 1% of GDP, pushing the deficit higher. Moreover, that figure has only increased with every new decision taken since then. Those measures include the natural gas VAT cut from October 1

st, with an estimated cost of 190 million euros for the remainder of the year (according to the Ministry of Finance), the rollover of free transport season tickets and expansion of the student scholarship scheme. By the end of the year, it is highly likely that the above-mentioned 1% will have increased by the odd decimal point.

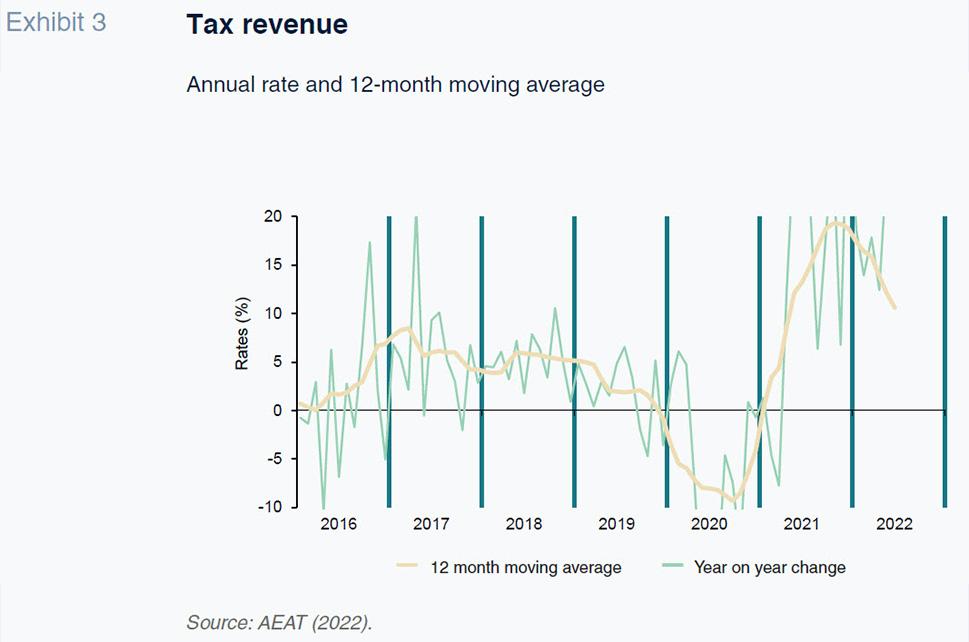

The positive and unexpected dynamics of tax collection are the reason why the increase in public spending and temporary tax relief are not having a significantly adverse impact on the deficit (Exhibit 3). Even though the drop in tax revenue was less pronounced than the collapse in GDP in 2020 by a wide margin, in clear contrast to the trend observed in 2009, the recovery in 2021 and the first half of 2022 implies tax revenue elasticities relative to GDP that are considerably above long-run estimates and are among the highest in the European Union today. The income support schemes (furlough, help for the self-employed) are certainly partly responsible for that positive result, as are the healthy job market dynamics being witnessed and, probably, the shrinkage of the shadow economy due to the boom in digital payments and a shift in the perceived risks and costs of remaining outside the official economy. Although we still lack accurate estimates of the relative weight of each of these three factors, it would be neither advisable nor prudent to assume that the current extraordinarily high elasticities will remain at these levels in the near future.

Outlook for 2023-2025

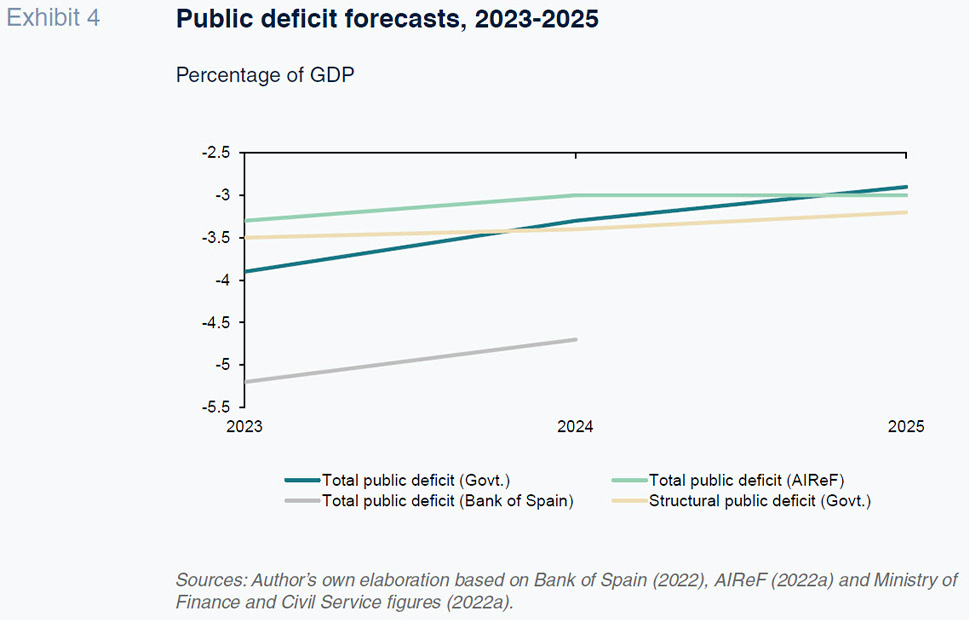

Exhibit 4 shows the forecast trend in the public deficit between 2023 and 2025 (Ministry of Finance and Civil Service, 2022a). Assuming a scenario of no-policy changes, the government expects the deficit to gradually trend down towards around 3% in 2025, shaped by a structural deficit which, despite a slight improvement, would remain above 3% that year. AIReF (2022a) supports that scenario on the whole, albeit with two caveats. Firstly, the fiscal authority is forecasting lower deficit reductions in 2023 and lower cuts the following two years. Secondly, its structural deficit estimate is higher than that of the government, still at roughly 4% in 2025. The Bank of Spain’s prognosis (2022) is more pessimistic. Without meaningful policy changes, it does not expect the deficit to improve significantly, remaining above 4.5% in 2023 and 2024.

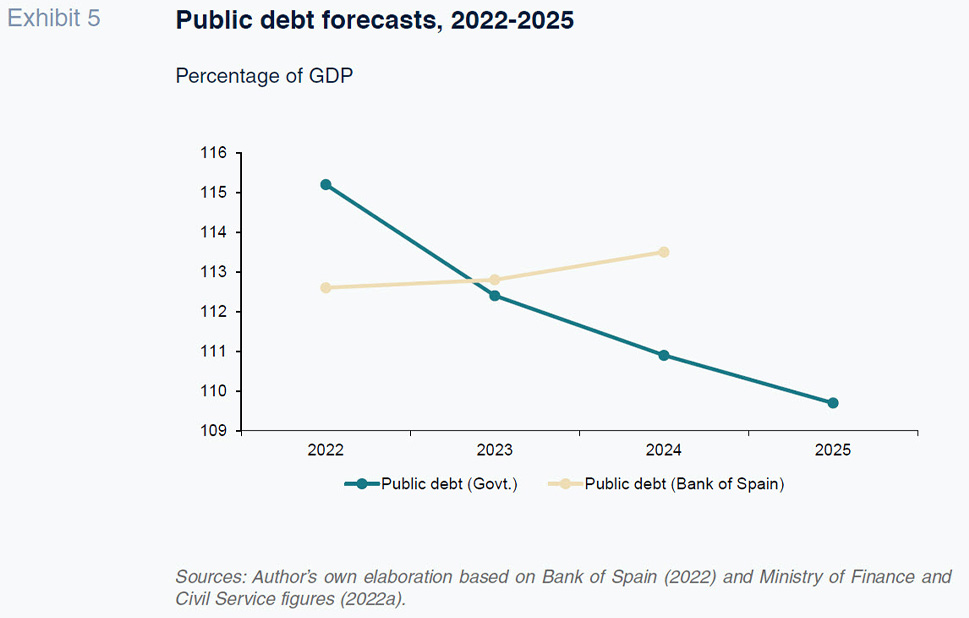

Exhibit 5 translates the above deficit picture into public debt terms. While the government is forecasting a very slow but steady reduction in the debt ratio, the Bank of Spain sees no prospect for improvement.

In short, it is not enough to hope for fiscal stabilizers and the improvement of the economic situation which, moreover, looks likely to be more complex in 2023 than was anticipated a few short months ago. Subject to a high degree of uncertainty, the current GDP forecasts are modest and are continually being revised downwards. From an political economy standpoint, it is fair to say that 2023 is looking particularly challenging for consolidation. Next year will be marked by a general election as well as elections at the municipal and regional levels, creating an incentive to spend more and freeze or cut taxes. Furthermore, the fresh rollback of the reinstatement of the European fiscal rules suggests that fiscal consolidation efforts will be rather restrained. Nevertheless, the above scenario is compatible with making an effort to define and negotiate a series of steps and a plan capable of generating confidence and credibility around Spain’s commitment to fiscal stability.

Considerations on policy action for the future

If we want to ensure compliance with the incoming European fiscal rules and the eligibility criteria for the new Transmission Protection Instrument, if we want to limit the country’s debt service burden in the medium-term and if we want to win back room for fiscal manoeuvre, now is the time to define reforms and targets that bring non-financial public spending and revenue closer in line. It is true that tax revenue is helping, that inflation, for now, is driving faster growth in revenues than disbursements and that the two new extraordinary taxes (for 2023-2024) on energy companies and financial institutions will generate, according to the government’s calculations, around 3.5 billion euros of additional tax revenue for every year they remain in force. However, the likely rollover in 2023 of measures intended to offset the effects of the war in Ukraine, the restatement of pensions in line with actual CPI and the additional budget expected to be allocated to defence spending will exert sharp pressure in the other direction.

Item #28 of Spain’s Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan contemplates far-reaching tax reforms which are scheduled for approval as early as the first quarter of 2023. Spain will negotiate the finer details with the European Commission in the autumn, at a time when progress on green taxation and incentives for decarbonisation and energy transition are likely to have to take a back seat. What makes sense against that backdrop is to articulate the overall shape of the reforms now and leave aside the parts that clearly contradict the compensatory measures in place at present and to activate the aspects that do not enter into conflict over the course of 2023.

On the spending side, pensions constitute the biggest outlay. The commitment to restate all pensions in line with the actual CPI readings observed in December 2021 and 2022 will imply a step effect in the 2023 budget, expenditure that was not contemplated and that will get consolidated going forward, further complicating the ability to meet the system’s projected budget figures. Item #30 of the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan details the initiatives underway, and others planned for the next decade in an attempt to render the pension system sustainable. However, there are doubts those measures will suffice (Bandrés, 2021).

Item #29 of the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan focuses on another key aspect of Spain’s public sector: public policy assessment. It is imperative to specify and accelerate attainment of the milestones constituting this component of the plan in order to eke out gains in public and fiscal spending efficiency in the very short-term. Progress on that front will unlock public sector savings and quality, which will in turn enhance citizens’ perceptions thereof. The same can be said of item #27, which addresses tax fraud. Here it is vital to accelerate initiatives and unlock results in order to reinforce the sufficiency of the tax system and enhance horizontal equity, which will ultimately boost taxpayer morale.

Lastly, in light of the likely extension to 2023 of some of the fiscal support measures introduced to tackle the effects of the invasion of Ukraine, the analysis performed by Checherita-Westphal, Freier and Muggenthaler (2022) is highly relevant. Their estimates for the Eurozone as a whole point to two undesirable features. The first is the mostly untargeted nature of the support being provided. Just 12% of the measures are focused on the most vulnerable households. The second is the fact that just 1% of the measures make a positive contribution to the green transition and decarbonisation. It would be desirable if, with more time to fine-tune the measures, both percentages were to increase substantially in order to maximise their redistributive impact, render the short-term initiatives compatible with the bigger challenges looming in terms of climate change and dependence on non-renewable energy sources, and limit their overall fiscal cost.

References

AEAT (2022).

Monthly Tax Collection Reports. June 2022. Retrievable from:

https://sede.agenciatributaria.gob.es/Sede/datosabiertos/catalogo/hacienda/Informe

_mensual_de_Recaudacion_Tributaria.shtmlAIReF (2022a).

Report on the 2022-2025 Stability Programme Update. May 5

th, 2022. Retrievable from:

www.airef.esAIReF (2022b).

Monthly stability target monitoring, 2022. July 7

th, 2022. Retrievable from:

www.airef.esBANK OF SPAIN (2022).

Macroeconomic projections for the Spanish economy, 2022-2024, June 10

th, 2022. Retrievable from:

www.bde.esBANDRÉS, E. (2021). Social Security budget for 2022: Short-term state support yet a need for structural reform.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 10(1). Retrievable from:

https://www.

sefofuncas.com/Spain%E2%80%99s-bumpy-post-COVID-19-recovery/Social-Security-budget-for-2022-Short-term-state-support-yet-a-need-for-structural-reformCHECHERITA-WESTPHAL, C., FREIER, M. and MUGGENTHALER, P. (2022). Euro area fiscal policy response to the war in Ukraine and its macroeconomic impact.

ECB Economic Bulletin, 5/2022. Retrievable from:

https://www.ecb.europa.euFUNCAS (2022).

Spanish Economic Forecasts Panel. September 2022. Retrievable from:

www.funcas.esHERRERO, C. (2022).

Testimony in Congress Before the Finance Committee. Report on the 2022-2025 Stability Programme Update. June 27

th, 2022. Retrievable from:

www.airef.esLAGO PEÑAS, S. (2022). Implications for Spain of the reform of the EU’s fiscal rules.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 11(2). Retrievable from:

http://www.sefofuncas.com/The-war-in-Ukraine-and-implications-for-Spain/Implications-for-Spain-of-the-reform-of-the-EUs-fiscal-rulesSPANISH MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND CIVIL SERVICE (2022a).

Stability Programme Update, 2022-2025. April 29

th, 2022. Retrievable from:

www.hacienda.gob.esSPANISH MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND CIVIL SERVICE (2022b).

Límite de gasto no financiero del Estado y tasas de referencia de déficit público 2023 [State non-financial state spending limit and public deficit targets for 2023]. July 26

th, 2022. Retrievable from:

www.hacienda.gob.esSPANISH MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND CIVIL SERVICE (2022c).

Ejecución presupuestaria de las Administraciones Públicas. [Budget outturn figures] September 2022. 12.9.2022. Retrievable from:

www.hacienda.gob.esTORRES, R. (2022). Responses to the energy crisis: The cases of Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, 11(3). Retrievable from:

http://www.sefofuncas.

com/Considerations-for-Spain-Geopolitical-risk-on-top-of-a-challenging-post-pandemic-recovery/Responses-to-the-energy-crisis-The-cases-of-Germany-France-Italy-and-Spain

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics at Vigo University and Senior Researcher at Funcas