Implications for Spain of the reform of the EU´s fiscal rules

Spain, being one of the countries hardest hit by the crisis and with pronounced fiscal imbalances, has a lot at stake in the process currently underway of reforming the EU´s fiscal rules. As various European and national actors debate their positions, Spain´s seat at the negotiating table could be further strengthened by a commitment to credible fiscal consolidation in the medium-term.

Abstract: There are currently two key fiscal processes playing out simultaneously across EU countries: i) a recovery in national finances following the tremendous shock caused by the pandemic; and, ii) the reform of the EU´s Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). The interplay of these processes is particularly key in Spain –a country that has been among the hardest hit by this crisis, with GDP contracting (-10.8%) in 2020, and expected to be among the last of the EU-27 to revisit pre-pandemic GDP levels. While Spain´s recent fiscal performance has been better than expected, this will likely prove temporary, and in the absence of structural changes aimed to address the country´s high level of structural deficit, Spain´s fiscal imbalances will remain among the highest in the EU-27 in 2024. Indeed, without a reduction in the structural deficit, the total deficit would stagnate at over 4% and public debt would continue to trend higher, reaching 135% by 2050. Going forward, the EU is set to resume the task of reforming its existing fiscal rule framework, with an eye to correcting the issues of the past and taking into consideration the impact of the pandemic on many member states´ performance on current targets. As different European and national actors debate their positions, Spain´s seat at the negotiating table would be strengthened if the country were to, in parallel, present a credible path towards fiscal consolidation.

Introduction [1]

We are currently watching two processes play out in the EU public finance arena. On the one hand, a recovery in national finances following the tremendous shock caused by the pandemic. On the other hand, reform of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). Although the two processes have different origins, they are now intertwined.

The revision of the bloc’s fiscal rules got underway just a few weeks before COVID-19 began its global spread; that effort was halted in order to activate the SGP escape clause to tackle the fallout from the coronavirus; and it was resumed towards the end 2021, by which time the fiscal panorama was worse and more asymmetrical than that observed in 2019. Public deficits and debt are further than ever from their limits of 3% and 60%, respectively, and the distance to target varies considerably by country.

In that context, Spain was one of the countries hardest hit by the crisis– it is still far from achieving pre-pandemic metrics and its fiscal imbalances are more pronounced than those of other countries. As a result, the reintroduction of the fiscal rules will prove a major challenge and the form their reintroduction takes will shape budget policy considerably over the coming years.

Spain has a lot at stake in the process of reforming the EU´s fiscal rules and it is essential to understand the matrix of possible solutions and strategies. Without a doubt, a commitment to fiscal stability is the way to prevent situations, such as the stress experienced with the risk premium during the GFC. However, that need not be incompatible with setting reasonable and feasible targets without triggering a bout of extreme fiscal austerity that would only prove counter-productive on account of its negative effects for the economy and politics.

The aim of this paper is to lay out the scenarios under debate in the European Union today and to outline where Spain stands, paying particular attention to the positions of the central government, the Bank of Spain and Spain’s independent fiscal institution, AIReF.

The outlook for Spain´s fiscal deficit and debt

Spain’s GDP contracted (-10.8%) by more than the EU-27 average in 2020 and the recovery staged in 2021 (+5.0%) does not make up for even half of the ground lost. Spain looks set to be the last country to revisit pre-pandemic GDP levels. Nevertheless, its public deficit has performed better than expected in 2020 and 2021. Without a doubt, the various income protection schemes have successfully weakened the link between contracting GDP and taxable revenue and paved the way for unexpectedly good news in terms of revenue dynamics. The forecasts for 2021 improved as the year unfolded and are currently all more optimistic than the official government forecast, established in the budget, which continue to call for a deficit of 8.4%. The Funcas consensus forecast (2022) is for a deficit of 7.3%; AIReF has weighed in at a lower 7.0% (AIReF, 2022a) and the Bank of Spain (2021) is currently forecasting a deficit of 7.5%.

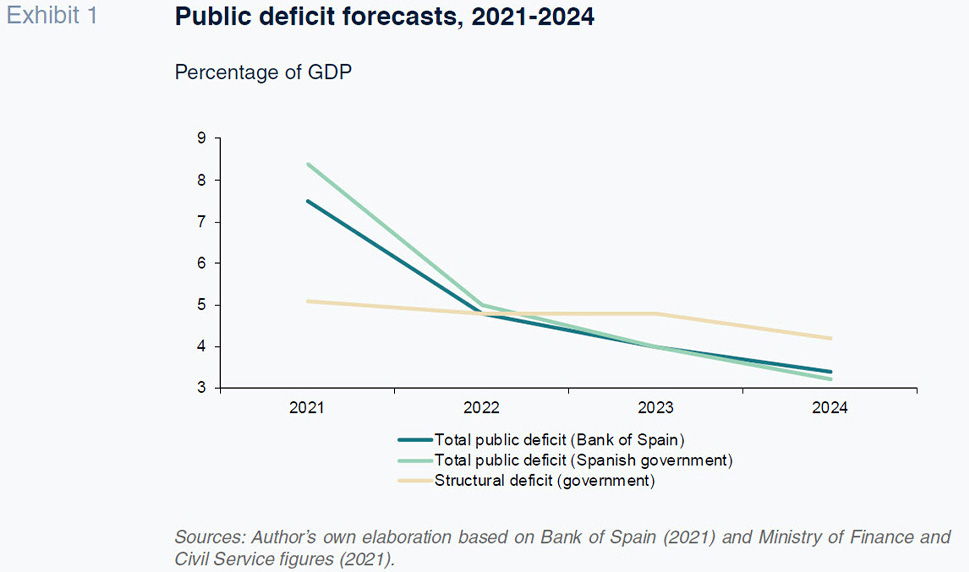

However, the favourable evolution of the deficit is likely to prove temporary and should not lead us to downplaying the gravity of the imbalances underlying Spain’s public finances. Exhibit 1 depicts the Spanish government’s and the Bank of Spain’s public deficit projections for 2021-2014, additionally mapping out the trend in the structural deficit,

i.e., the amount of the budget deficit not attributable to cyclical dynamics. The cyclical component will be neutral in 2022 and will reduce the overall deficit in 2023 and 2024. Note that all three plot lines meet at around 5% in 2022; in 2024, the overall deficit is still above the 3% threshold with the structural deficit at over 4%. Furthermore, depending on the final duration of the conflict in Ukraine, these figures could deteriorate significantly.

In other words, in the absence of structural changes in the taxation system and/or spending cuts, the structural deficit will remain close to the highs reached in 2020-2021, making Spain one of the countries in the EU-27 with higher total and structural deficits. According to the projections of the EU Independent Fiscal Institutions Network (2021a), in 2024 the five countries with the highest overall deficits will be the Czech Republic, Belgium, France, Slovakia and Spain.

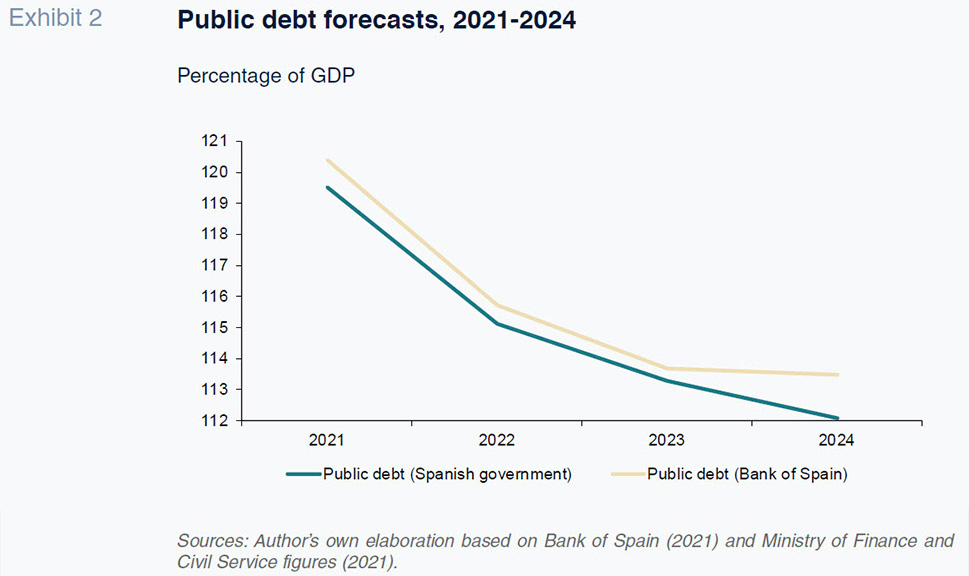

The deficit situation spills over to the public debt scenario depicted in Exhibit 2. It is true that the recovery in nominal GDP in 2021 and 2022 and the growth forecast for 2023 and 2024 will drive substantial growth in the debt-to-GDP ratio’s denominator, pushing public sector leverage down from the peak of 2020, of around 125%, to levels closer to 113%. However, in 2024 Spain would remain within the EU-27 quartile of most heavily indebted countries, alongside Greece, Italy, Portugal, France and Belgium, still more than 50 percentage points of GDP above the current threshold of 60%, which only 14 of the EU-27 would manage to comply with (EU Independent Fiscal Institutions, 2021a). Combining the public debt and deficit figures, leaving Greece

–an outlier– aside, and assuming no new revenue or expenditure measures, France, Belgium and Spain are the three countries with the most imbalanced fiscal situations in the medium-term.

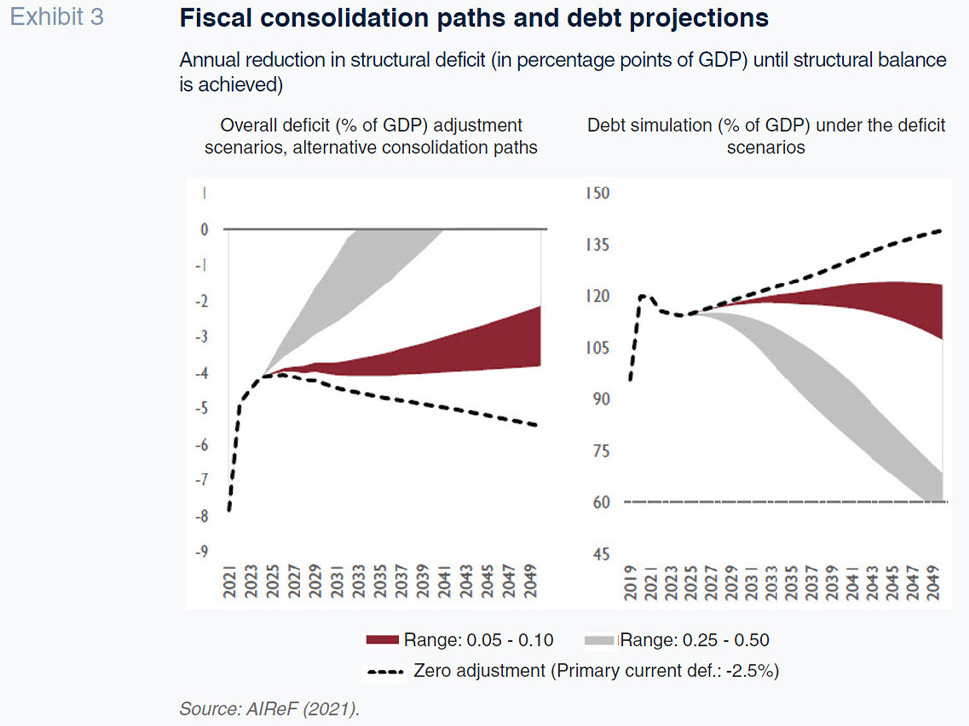

Exhibit 3 provides complementary insight into the scale of the pending fiscal adjustment (AIReF, 2021). The left-hand panel shows the projected trend in the total deficit under three scenarios: an annual reduction in the structural deficit of between 0.05% and 0.10% of GDP; a bigger adjustment, of 0.25%-0.50%; and a no-change scenario, in which the primary structural deficit remains constant at 2.5%. The right-hand panel depicts the consequences of those scenarios for Spain’s debt-to-GDP ratio. To eliminate the total deficit by the end of the decade, Spain would have to slash its structural deficit by more than half a point of GDP each year. And even with an adjustment of that magnitude, it would take more than 20 years to bring debt-to-GDP under 60%. Without cutting the structural deficit, the total deficit would stagnate at over 4% and public debt would continue to trend higher, reaching 135% by 2050.

It is clear that Spain must tackle its structural deficit problem and clean up its accounts, having failed to do so in the past. That being said the new fiscal rules need to assume that bringing debt below 60% within the decade is a target that Spain and other countries in a similar predicament are unlikely to be able to achieve.

The outlook for reform of the current fiscal rules

On October 19th, 2021, the European Commission officially resumed a review of its fiscal rules with the aim of coming up with a concrete proposal, debating it and reaching agreement in 2022, which would enter into force in 2023 (European Commission, 2021); although it is true that, depending on the final economic impact of the invasion by Russia of Ukraine, this timeline could be extended another year. Framed by broader reform of the EU’s fiscal policy framework, which is set to include new supranational risk-sharing and investment financing instruments (related in particular to environmental sustainability and digitalisation), the need for the reform of the EU´s exiting fiscal rules became evident in 2020 and has only been reinforced in 2022 (Feás et al., 2021). Rules that have proven complex and hard to apply, that have failed to neutralise the pro-cyclical effect of fiscal policy and whose credibility has become impaired. Rules, in short, that need to be replaced by a new framework designed to correct those issues and take stock of how the pandemic has moved many EU-27 nations’ public deficit and debt metrics further than ever from the benchmark thresholds in place since the end of the 1990s, when interest rates and potential outputs were different than those we are observing and projecting today.

As is only logical, the European Commission has yet to take an official position. However, we do know where very important institutions’ thinking is headed and there appears to be a degree of consensus. The European Fiscal Board (2021), consistent with its stance since 2018, suggests replacing the current framework with three complementary elements: a medium-term debt anchor; a simple expenditure benchmark with a built-in debt brake; and a general escape clause. It also defends keeping the 3% threshold for public deficits, calls for reinforcing the supervision and oversight carried out by the national fiscal authorities and acknowledges that the debt anchor would have to be adapted for the conditions prevailing in each country.

The European Central Bank (ECB, 2021) has taken a similar stance, albeit less concrete, likewise advocating for a more prominent spending rule and agreeing on the need for a realistic, gradual and sustained reduction in public debt. The manifest signed by the finance ministers of Austria, Denmark, Latvia, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Finland, Netherlands and Sweden in September 2021 is even less precise but emphasises the need to reduce public debt ratios and adapt the prevailing rules without jeopardising fiscal sustainability. The manifest underscores that reform quality should count more than speed, opening the door to reactivation of the existing rules until such time as an agreement is reached (Blümel et al., 2021). However, that would create a dilemma for the European authorities, who would be faced with choosing between reapplication of the existing rules, thus generating an intense negative shock for GDP and employment across a considerable number of member states, or accepting widespread breach of those rules, ruining the framework’s credibility altogether.

In short, it is unlikely that fiscal rule reform will culminate in a radically different approach, such as that proposed by Blanchard, Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2021), who call for doing away with all numerical rules. Note additionally, that although there is some consensus around the general approach, many aspects of the spending rule and potential benchmark debt levels still have to be pinned down. It is also conceivable that the expenditure rule will be based on structural budget balance instead of a debt target, so implying smaller-scale reforms (EU Independent Fiscal Institutions, 2021b). That could be a plus from the economic policy standpoint.

State of play

The existence of differing positions among the member states’ governments regarding how the fiscal rules should be reformed and the need to reach an agreement over the course of 2022 explains the prudent tone and, above all, lack of specifics we are seeing in public posturing. As with the fewer than 400 words issued by the ministers of finance in the above-mentioned manifest, we need to comb through public statements made by Spain’s Minister for Economic Affairs, Nadia Calviño, for clues as to where the Spanish government stands. One of her clearest interventions took place at a meeting with the President of the Eurogroup on February 7th, 2022, (Calviño and Donohoe, 2022) in which she called for a realistic and pragmatic budget consolidation roadmap, with deficit and debt reduction pathways adapted for each country’s situation in order to shore up their public finances in the long-term, while facilitating growth, quality job creation and investment in the twin green and digital transition in parallel.

Her words address two different claims. The first has to do with the need for adjustment paths adapted for the diverse universe of fiscal parameters and is completely reasonable from the point of view of Spain’s economy and vital for the reasons outlined previously. However, her claim that certain investments should be left out of the calculations may be harder to sell, due to the problems that tend to affect such exemptions or ‘golden rules’, namely the issues encountered in drawing the eligibility line and the evidence that they tend to contribute to the accumulation of financial liabilities in the same manner as eligible expenses (AIReF, 2022). At any rate, that issue could fade to the background to the extent that the Next Generation EU instrument, a pan-European investment mechanism focused precisely on enabling the twin transition, becomes a permanent feature of the EU’s governance architecture (Feás et al., 2021).

The AIReF is clearer about where it stands (2022). Spain’s fiscal institution is in favour of the three-pronged solution comprising a net primary spending rule, a long-term debt anchor (for which the benchmark could be left at 60%) and an escape clause. The AIReF makes three further clarifications. The first is that it would be compatible to leave the long-term benchmark of 60% in place for all countries and, in parallel, set specific interim targets for each country that give rise to asymmetric paths for convergence towards the long-term anchor. The second is that although the structural deficit would lose its current function, it should be left as an input for proposed expenditure path assessment purposes, alongside the debt anchor. The third is that “green” investments should not be carved out from the spending rule but addressed using centralised fiscal instruments, as suggested above.

Lastly, the document by Alloza et al. (2021) provides a glimpse into where the Bank of Spain, the country’s other important independent body in the area of fiscal policy analysis and oversight, stands. The central bank also advocates for a spending rule, debt anchor and escape clause but emphasises other key aspects. The first is understanding that the spending rules are part of the EU’s fiscal policy governance architecture, which also includes supranational instruments for risk-sharing in the event of symmetrical and asymmetric shocks, the structural reform agendas, greater integration of the EU’s capital markets and completion of the final phase of the banking union project. The second is that the reforms should not enshrine the 3% and 60% thresholds, but rather recalibrate them in light of the current macroeconomic conditions (interest rates, potential growth) and the economies’ structural transformations. The third relates to the need to address the asymmetries in fiscal positions from 2022 either by setting debt anchor convergence paths at different speeds or creating “redemption funds” at the European scale to even out the countries’ starting positions. Lastly, Alloza et al. (2021) emphasises a few additional matters that could reinforce compliance with the fiscal rules, specifically, coordinated national fiscal policies and the role of the independent fiscal institutions at both the European and national levels.

Conclusions

Budget consolidation in Spain is not merely necessary to comply with external rules. Fiscal stability is worthwhile in its own right and social and political commitment is needed to map out a credible and coherent medium-term strategy. Structurally imbalanced public accounts curtail the ability to respond to future crises, leave Spain vulnerable to international financial volatility, harm the country’s reputation and standing in international economic forums and distort the relationship between the benefits of spending and the sacrifices implied by the associated taxes, passing the burden on to future generations.

The European fiscal rules need to be reformulated and adapted and it is very reasonable to demand that they be adapted for the various countries’ different realities. However, Spain’s position at the negotiating table would be stronger if, in parallel to presenting its demands, it presented a credible fiscal consolidation plan for gradually but steadily correcting its structural deficit.

Notes

The author would like to thank Diego Martínez López and Javier Pérez for the feedback and suggestions.

References

AIReF (2021). Debt Observatory. November 2021. Retrievable from

www.airef.es AIReF (2022a). Monthly stability target monitoring, 2021. January 1

st, 2022. Retrievable from

www.airef.es AIReF (2022b). AIReF’s contribution to the public consultation of the European Commission about the reform of the European fiscal framework.

Working Paper, 1/2022.

www.airef.es ALLOZA, M., ANDRÉS, J., BURRIEL, P., KATARYNIUK, I., PÉREZ, J. and VEGA, J. L. (2021). The reform of the European Union’s fiscal governance framework in a new macroeconomic environment.

Occasional Papers, 2021. Bank of Spain.

BANK OF SPAIN (2021). Macroeconomic projections for the Spanish economy (2021-2024), December 17

th, 2021. Retrievable from

www.bde.es BLANCHARD, O., LEANDRO, A. and ZETTELMEYER, J. (2021). Redesigning the EU fiscal rules: From rules to standards.

Economic Policy, 36(106), pp. 195-236.

BLÜMEL, G., WAMEN, N., REIRS, J., MATOVIC, I., SCHILLEROVÁ, A., SAARIKKO, A., HOEKSTRA, W. and ANDERSSON, M. (2021). Common views on the future of the Stability and Growth Pact. September 9

th, 2021. Retrievable from

www.bmf.gv.at CALVIÑO, N. and DONOHOE, P. (2022).

Conversation with Nadia Calviño and Paschal Donohoe on the “Opportunities for the euro area in the context of the recovery” – Elcano Royal Institute.

ECB (2021). Euro system reply to the Communication from the European Commission “The EU economy after COVID-19: implications for economic governance”, October 19

th, 2021.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2021). The EU economy after COVID-19: Implications for economic governance, COM (2021) 662 final, October 19

th, 2021.

EUROPEAN FISCAL BOARD (2021). Annual Report 2021. Retrievable from

https://ec.europa.eu/European-fiscal-board EU INDEPENDENT FISCAL INSTITUTIONS (2021a). European Fiscal Monitor. June 2021. Retrievable from https://www.euifis.eu EU INDEPENDENT FISCAL INSTITUTIONS (2021b). EU fiscal and economic governance review: A contribution from the network of independent EU fiscal institutions. Retrievable from https://www.euifis.eu FEÁS, E., MARTÍNEZ, C., OTERO-IGLESIAS, M., STEINBERG, F. and TAMAMES, J. (2021). A proposal to reform the EU’s fiscal rules. Elcano Policy Paper. FUNCAS (2022). Spanish Economic Forecasts Panel. March 2022. Retrievable from

www.funcas.es MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND CIVIL SERVICE (2021). Stability Programme Update, 2021–2024. April 30

th, 2021. Retrievable from

www.hacienda.gob.es

Santiago Lago Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics and Director of the Governance and Economics Research Network (GEN), Vigo University