The resilience of Spain’s manufacturers in the face of COVID-19

In comparison with peer countries, Spain’s manufacturing output held up relatively well amidst a historic contraction in GDP. That said, despite its strong track record in job creation prior to the crisis, the number of hours worked and employees in the manufacturing sector fell as a result of the pandemic.

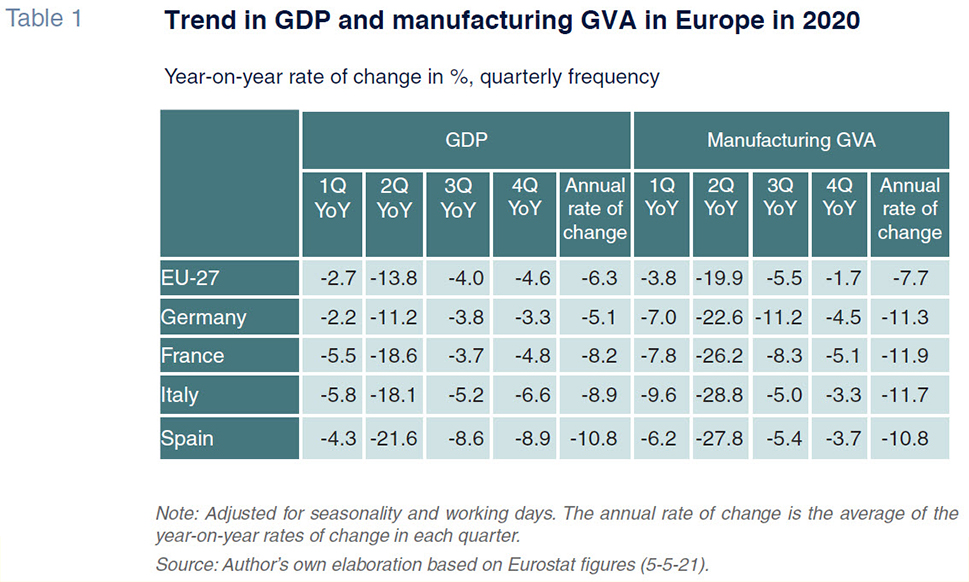

Abstract: While Spain’s GDP contracted by more than the other core EU countries in 2020, its manufacturing sector has proved surprisingly resilient. At 10.8%, the Spanish manufacturing sector’s GVA posted the smallest contraction, with Germany’s manufacturing GVA plunging by 11.3%, more than double its fall in GDP. Admittedly, part of this is explainable by the fact that tourism, a key sector for Spain, collapsed in 2020, weighing heavily on GDP. Also relevant is the fact that Spain entered the crisis after several years of stronger growth in output in the manufacturing sector compared to Germany, France and Italy. Notably, the recovery in Spanish manufacturing took longer to emerge due to the prolongation of lockdown measures compared with peer countries. However, by December 2020, Spanish manufacturing production was down just 2% year-on-year. In terms of manufacturing employment trends, Spanish firms had a strong record of job creation going into the crisis. However, by the second quarter of 2020, the number of hours worked in the manufacturing industry had fallen significantly, with job losses rising incrementally despite the temporary job protection scheme.

Introduction

The year 2020 will be remembered for the pandemic, the extraordinary pressure it exerted on healthcare systems, and the sharpest peace time contraction in economic activity. In this paper, we analyse the trend in production and employment in the manufacturing sectors of the four largest economies in the EU-27: Germany, France, Italy and Spain. Although the focus is on 2020, we also analyse the trends in the run-up to the crisis in order to explain the reasons for the differing reactions to the pandemic.

The most important conclusion is that the strong performance of Spain’s manufacturers since 2017 limited the contraction in real GVA in 2020 to just 1% using 2015 as the base year. Germany, France and Italy were in a weaker position at the start of the pandemic, which has translated into a slower recovery. Although Spain’s GDP contracted by more than its peer countries, its manufacturing sector has proven more resilient.

Gross value added by manufacturers relative to GDP The trend in manufacturing GVA and GDP in the four European economies is depicted in Exhibit 1. The first thing of note is the profound V-shaped recession triggered by the pandemic, with the collapse in the second quarter of 2020 followed by a sharp recovery in the following quarter.

Second, the correction in manufacturing activity for each country in the second quarter was more pronounced than that of their respective GDP performance. In Spain, the year-on-year decline in manufacturing GVA reached 27.8%, compared to a GDP contraction of 21.6% (Table 1). The reason is that many manufacturers had to shut their doors between the third (or fourth) week of March and the end of April, either on account of the strict lockdown or the lack of supplies (many of which come from China). The supply issues forced the production chains to pause for longer than was strictly necessary while economies froze during lockdown.

However, during the third and fourth quarters, those economies more dependent on tourism —Spain and Italy— saw the recovery in their GDP lag that of manufacturing GVA. While most factories were able to reopen, business activity in the hospitality and tourism sectors collapsed. For that reason, Spanish GDP sustained the biggest contraction of the four major economies, amounting to 10.8% in 2020. By comparison, Germany saw a much narrower decline of 5.1%. However, at 10.8%, the Spanish manufacturing sector posted the smallest contraction of any of the economies analysed. Germany’s manufacturing GVA contracted by 11.3%, which is more than double its fall in GDP (Exhibit 1.B).

These data support the thesis that the Spanish manufacturing sector has proven more resilient. That relative strength may be attributable to the fact that Spanish manufacturers benefitted from far more solid growth momentum prior to the pandemic. Between 2017 and 2019, their GVA was growing at an average annual rate of 2.8%, compared to just 0.6% and 0.3% in Italy and France, respectively. German manufacturing did not grow during that period, which is consistent with the fact that its manufacturers staged such a mediocre performance in 2020 in comparison with the rest of its economy.

That being said, the pandemic had a massive adverse impact on industry in all four of the European Union’s largest economies, marked by double-digit contractions in sector GVA.

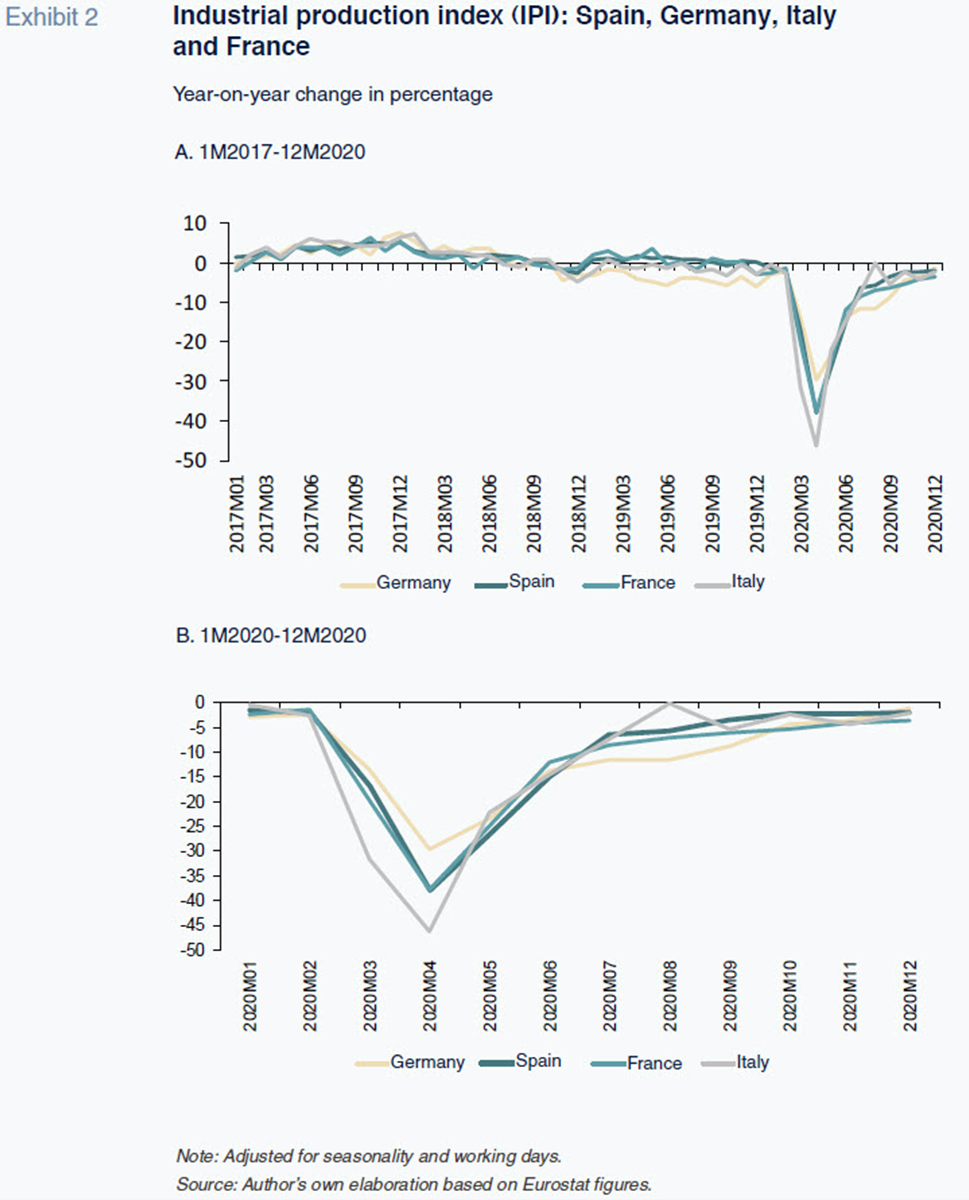

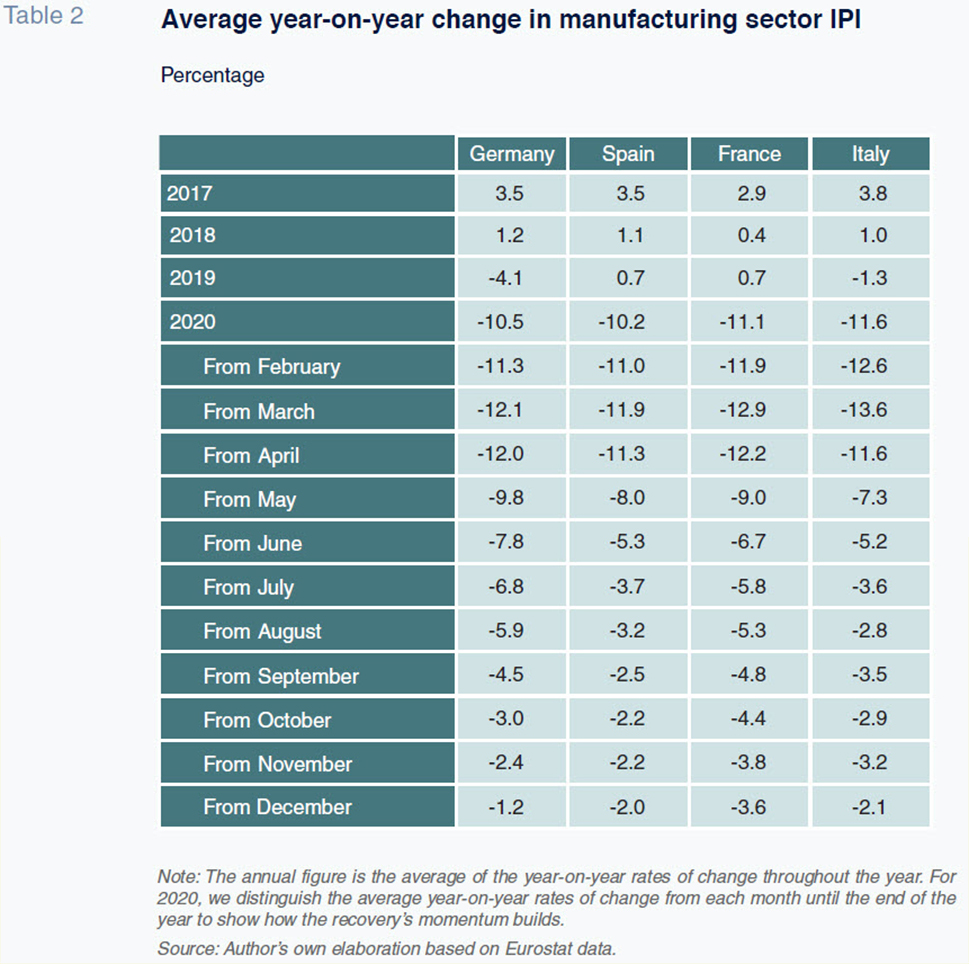

Collapse and recovery in manufacturing activityIn this section, we analyse the monthly industrial production index (IPI) figures. Exhibit 2 provides the year-on-year rate of change in the IPI in Spain, Germany, France and Italy. Notably, European manufacturing activity had been slowing since 2018. In 2019, German manufacturers showed clear signs of recession. In Spain, although growth had eased, the year-on-year rates of change remained in positive territory throughout 2019 (Moral, 2019).

In January and February 2020, when the talk was still of a virus contained in China, the year-on-year numbers turned negative for the first time due to the lack of supplies from Asia. In March, the contraction was initially sharper in Italy, as COVID-19 had forced the industrial northern region of the country to shut down earlier that month. In Spain, Germany and France the pandemic took a little longer to take hold, as did the attendant lockdown measures, cushioning the impact in March somewhat. By April, output turned negative in all four countries. The annualised contraction in manufacturing output peaked at 46.3% in Italy, followed by Spain, France and Germany, where the collapse in production peaked at 38.1%, 37.7% and 29.7%, respectively. Never before had there been negative output readings of such severity. In Spain, for example, in the toughest months of the previous crisis, the fall in production bottomed out at 22%.

From May, the recovery in manufacturing mirrored the easing of social distancing restrictions. As a result, Spain’s manufacturing recovery was slower than that of both France and Italy. Fortunately, the collapse in activity did not last for long. In July there were already signs of recovery, except in Germany. However, it would take until September for the year-on-year negative rates to return to within a range of 10% (in absolute terms).

The monthly IPI figures provide a fuller picture of the trajectory back to pre-pandemic levels. Until then, the changes in trend were less perceptible with the annual data containing more information. However, a collapse of this magnitude warrants closer attention to the monthly movements for insight into the strength of the recovery.

The first four rows of Table 2 show the annual change in the IPI as the average of the year-on-year changes in the 12 months of the year. These figures confirm the slowdown in industrial production in 2018, which turned into a contraction in Germany and Italy the following year. That is the context in which the pandemic occurred. The Spanish manufacturers performed relatively better, registering an annual decline of 10.2% in 2020.

The second group of figures in Table 2 provide the key to tracking how manufacturing production has fared month by month. From February on, the numbers represent the average of the year-on-year rates for the remaining months of the year. From May the turnaround emerged in all four economies. The return to pre-pandemic levels was very robust, despite the advent of a second wave. The negative rates have been narrowing month after month, revealing very narrow contractions by December 2020. Spain’s manufacturers produced just 2% less that month than in December 2019. In Germany, which had posted a weaker recovery initially, production has recovered strongly since November, with the country producing only 1.2% less than a year earlier by December. Note that the quarterly figures did not catch that change in trend, which took place later.

Impact on European manufacturing jobs

Temporary job protection measures in Europe

The reduced demand for labour is evident from the activity analysis conducted above. This situation was common to virtually all sectors of the economy, prompting the European Union to introduce the Support to Mitigate Unemployment Risk in an Emergency (SURE) fund for 19 member states. Of the four countries analysed, only Italy and Spain received assistance from that fund (SURE, 2021).

The need for employment protection peaked in April 2020. Since then, the number of workers covered by the various schemes has fallen gradually

[1], although the persistence of the pandemic has necessitated the extension of labour support schemes into 2021. In some countries, the number of people affected increased in January and February 2021.

Germany has used a protection measure that already existed in its labour legislation, known as Kurzarbeit, or short-time work benefits. It is a fund that is capitalised by employer and employee contributions (and by the state in exceptional circumstances) and reimburses part of employee salaries at firms forced to scale back their activity. According to the Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2021), 17.9% of all job holders were enrolled in the Kurzarbeit program in April, a figure that fell to 7.1% by December.

In France, Decree 2020-325 of March 25th, 2020, modified the partial unemployment coverage (chômage partiel) provided to enterprises. According to la Dares (2021), in April 2020, some 8.4 million French workers were under that scheme and by January 2021, 2.1 million (7.5% of job holders as of 4Q20) were still enrolled in it.

In Italy, an existing coverage scheme —Cassa Integrazione Guadagni— was also modified to expand it for the workers covered by temporary reductions in activity. According to Istat (2021), as many as 5.36 million workers were covered by that scheme in April, falling to 972,000 by September.

In Spain, the existing redundancy scheme legislation —the ERTE instrument— was also amended

[2] to allow the furlough of workers affected by reduced activity at companies due to COVID-19. The number of Spanish employees on furlough peaked at 3,576,078 in April (19.4% of social security contributors as of the end of April 2020) and 755,613 were still on the scheme in December (4.0% of year-end 2020 contributors). As already noted, Spain received financing from the SURE fund. It received the last payment on March 16

th, 2021, putting the total received at 13.9 billion euros. Of the 19 recipient member states, Spain ranks second to Italy in loans approved through the SURE scheme. Italy has had 27.44 billion euros of SURE loans approved, of which 24.82 billion euros had been received as of March 18

th, 2021.

Trend in manufacturing jobs

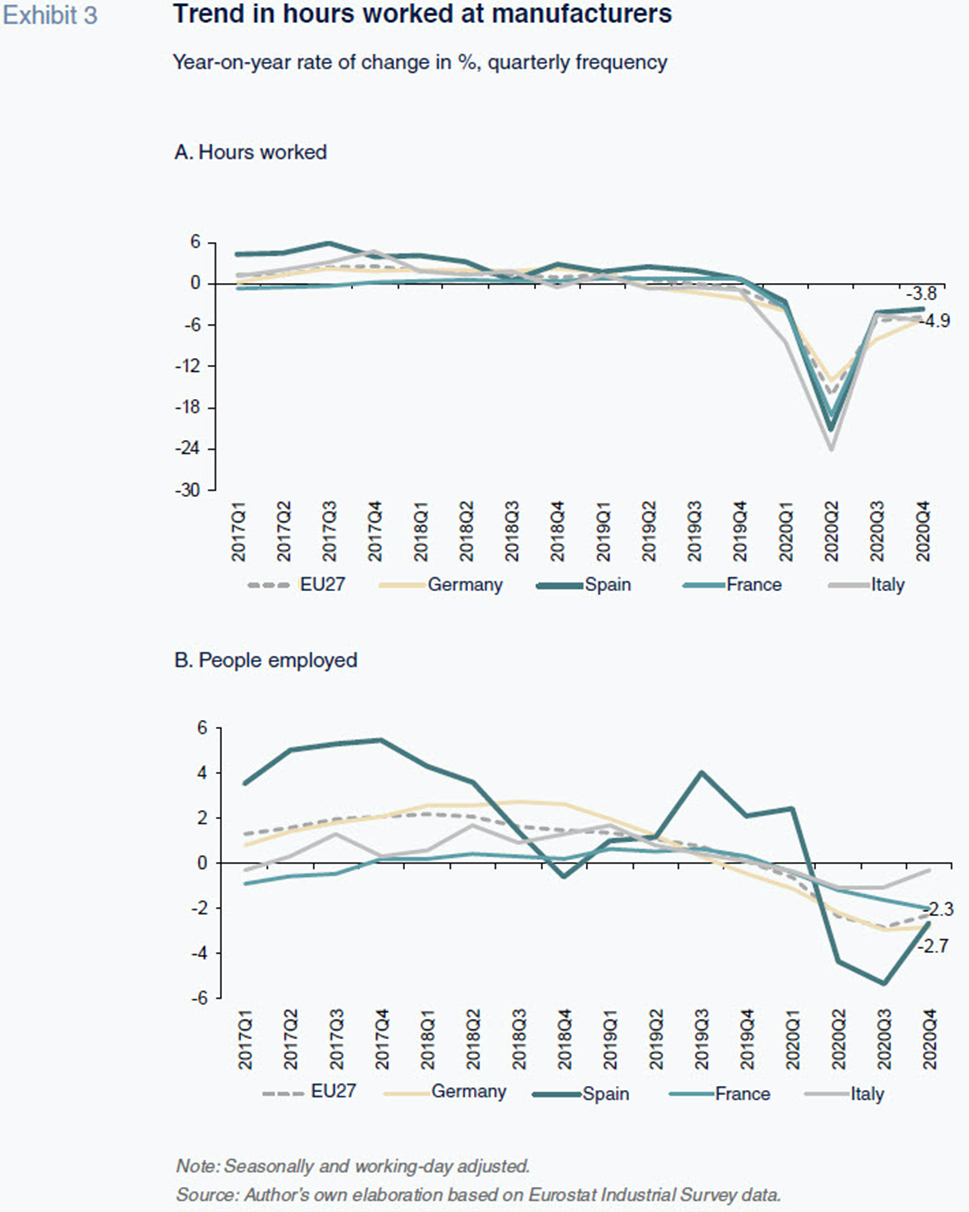

The furloughed employee figures provided in the last section are totals and therefore correspond mostly to tourism sector jobs. However, it is important to consider those temporary protection schemes given that they should mitigate the drop in employment relative to the number of hours effectively worked in the manufacturing industry (Exhibit 3).

Before the pandemic, with the exception of the fourth quarter of 2018 and the first quarter of 2019, Spain’s manufacturing companies were creating jobs at a faster rate than manufacturers in the other countries analysed and faster than the EU-27 on average. During that period, the number of people employed in Spain increased by 2.3%, compared to 1% in the EU-27 (average year-on-year rates between 1Q17 and 4Q19).

With the onset of the pandemic, and in line with the trend in production already analysed, the number of hours worked decreased significantly in the second quarter. Meanwhile, thanks to the temporary job protection schemes, the decrease in the number of job holders was lower and occurred incrementally. However, Spain registered a more significant reduction in the number of job holders.

The Spanish economy’s initial ‘overreaction’ may be attributable to the flexibility afforded by the higher percentage of temporary contracts. That has prompted companies to terminate those contracts instead of opting for the furlough scheme. This suggests that the trend of sharper job destruction in the Spanish economy during recessionary events observed in prior recessions continues to hold (López and Malo, 2015). Importantly, the protection offered by the furlough scheme is only valid for companies that remain operational. If a company shuts down permanently, its employees are considered as unemployed.

Conclusion

By the final months of 2020, production in the manufacturing sectors of the EU’s core economies was approaching 2019 levels. By December 2020, France was still under its pre-pandemic output level by 3.6%, followed by Italy at 2.1%, Spain at 2% and Germany at 1.2%. Spanish manufacturers staged a more sustained recovery throughout the second half of 2020, which, coupled with their strong performance since 2017, has kept the contraction in real GVA at just 1% compared to 2015 levels. Therefore, despite the underperformance of the Spanish economy as a whole, the manufacturing sector has staged a remarkable recovery. The bad news remains the job market, where the presence of the furlough scheme has not prevented a more pronounced fall in employment levels.

Notes

Gómez and Monte (2020) studied the labour market in most EU-27 member states (Germany is not included) in the first and second quarters.

On March 17th, 2020, via Royal Decree-Law 8/2020, extended in September 2020 (RDL 30/2020) and January 2021 (RDL 2/2021).

References

BUNDESAGENTUR FÜR ARBEIT (2021).

Hochrechnung der realisierten Kurzarbeit Dokumentation des erweiterten Verfahrens. Retrievable from:

http://statistik.arbeitsagentur.deDARES (DIRECTION DE L’ANIMATION DE LA RECHERCHE), MINISTÈRE DU TRAVAIL, France (

https://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr)

GÓMEZ, A. L. and MONTERO, J. M. (2020). The impact of the lockdown on the euro area labour market in 2020 1H.

Economic Bulletin, 4/2020. Bank of Spain.

ISTAT (ISTITUTO NAZIONALE DI STATISTICA) (2021).

Il mercato del lavoro 2020. Una lettura integrata. LÓPEZ, E. and MALO, M. A. (2015). The Spanish labour market: The European context, two old challenges and a new problem.

Ekonomiaz, 87 (First Half), pp. 32-59.

MORAL, M. J. (2019). Evolución comparada de las manufacturas españolas. Cuadernos de Información Económica, 273, pp. 45-54.

SURE. The European instrument for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency. In

https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/financial-assistance-eu/funding-mechanisms-and-facilities/sure_en

María José Moral. UNED and Funcas