Export-led growth in the euro area: Benefits and costs

The eurozone’s growth model is based on dynamic export markets, compensating for chronically weak domestic demand, leading to an external surplus which has become the largest in the world. The worsening global context and the decreasing return on the eurozone’s external surpluses call this model into question.

Abstract: The European Central Bank has recently cut its forecasts, projecting the eurozone will expand by just 1.2% in 2019. Although, to some degree, temporary factors play a role in the region’s slowdown, an alternative explanation for such lacklustre performance is the tendency within Europe to rely on export markets in order to compensate for a chronic weakness of domestic growth factors. Prior to the financial crisis, domestic demand increased by 1.9%, annually. However, since the start of the crisis, this growth record has deteriorated dramatically across even the core eurozone countries. Thus, the eurozone’s recovery is largely due to the opportunities in export markets, which have compensated for sluggish domestic demand. This is illustrated by the fact that the bloc’s external surplus stood at 400 billion euros, the largest in the world. Significantly, recent trends show domestic demand is not responding in the face of declining exports, nor have rising national savings coincided with increased investment in the eurozone’s productive capacity. Unfortunately, European macroeconomic policy has limited tools to address these trends and support an expansion of domestic demand.

[1]

Introduction

According to its latest projections released in June, the ECB expects the eurozone economy will grow by a mere 1.2% this year, which represents a significant cut from the previous round of projections published last Autumn (ECB, 2019). While the forecasts suggest the economy will rebound slightly next year, the expansion is still below potential growth rates.

It is often claimed that the advent of this unpredicted slowdown reflects adverse external factors. These include the intensification of protectionism, the abrupt decline in Chinese economic growth, and turbulence in emerging economies. Relatedly, world trade is expected to grow by a disappointing 0.7%, compared to nearly 5% last year.

[2] The manufacturing sector, as well as the most export-dependent economies, such as Germany, are disproportionately affected by these dynamics. Uncertainty over Brexit is an additional cloud on the horizon, while other factors such as a global adjustment in the automobile industry also play a role.

Although these external or temporary factors are undoubtedly important, internal constraints could offer an alternative explanation for lacklustre growth. Of particular importance is the tendency within Europe to rely on export markets in order to compensate for domestic weaknesses. Significantly, unlike external constraints, which fall largely outside the purview of European policymakers, internal growth factors can be tackled by well-designed measures. The purpose of this paper is to describe the export-led growth approach, analyse its associated benefits and costs, and discuss the role of macroeconomic policies in rebalancing the European economy.

Exports as a safety valve for a chronic shortage of domestic growth

The internal engine of eurozone growth has failed to power a broad economic expansion. In the years after the euro’s launch, there was relatively strong growth in domestic demand –the sum of domestic consumption and investment. During the period of 2000 to 2007, domestic demand increased on average by a respectable 1.9%, annually.

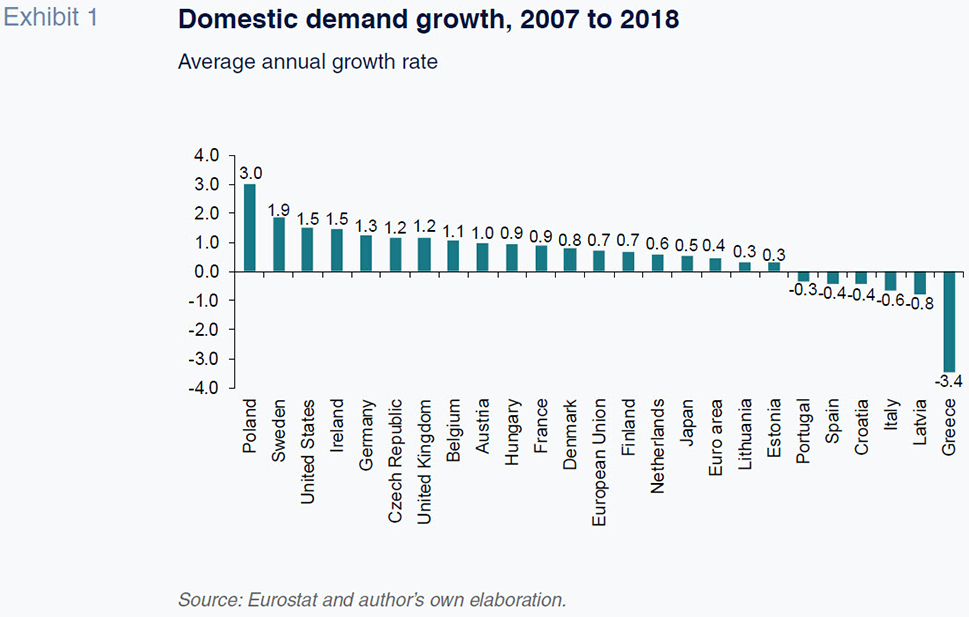

However, since the start of the crisis, eurozone domestic demand has grown by a modest 0.4%, annually, on average (Exhibit 1). The fastest growing European economies, Poland and Sweden, do not even belong to the single currency. The US –where the crisis originated– outperforms the eurozone by a wide margin. Even Japan does marginally better than the eurozone. The only exception to this general post-crisis pattern is Germany, whose robust growth was preceded by a pre-crisis economic slump. In fact, between 2000 and 2018, domestic demand in Germany rose by less than both the European and US average.

While the post-2007 period covers both the crisis and recovery phases, performance has been below international standards in both sub-periods. Eurozone domestic demand was slightly more impacted by the crisis than the rest of the EU or the US. Furthermore, recovery started later and was weaker than in other regions. Only Japan seems to have performed as weakly in terms of domestic demand after 2007.

It could be argued that sub-par demand growth is just an outcome of averaging participating countries, with some of them facing difficulty sustaining the single currency. However, it is worth noting that even some of the core eurozone economies do not perform particularly well when compared with their non-eurozone counterparts. For example, while Finland posted similar growth rates to Sweden before adopting the euro, Sweden’s expansion has since proved stronger. Comparisons of France and Spain with the UK, or Germany with the US, result in similar observations. Not to mention Italy, which has become an outlier of its own. This country faces a stagnation of real spending since the euro was created, which may explain today’s pessimism among the majority of Italians concerning their economic prospects.

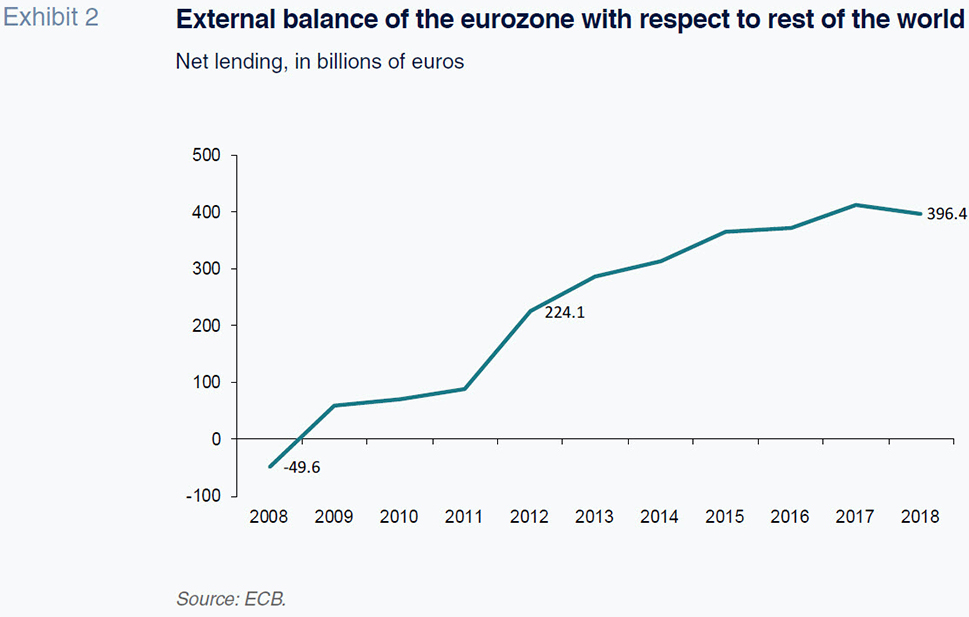

The recovery phase is largely a reflection of the eurozone’s ability to seize the opportunities of growing export markets, as this has proved to be the sole way to compensate for sluggish domestic demand. This has contributed to a growing external net lending position (henceforth external surplus), which has reached historical proportions (Exhibit 2). While on the eve of the financial crisis the external account was broadly balanced, it reached a surplus of nearly 400 billion euros in 2018, or around 3.8% of GDP.

Importantly, the external surplus is the largest in the world, exceeding China’s by 100%. It also represents two thirds of the US deficit, which is one of the motivations behind the protectionist discourse in that country. It too is interesting to note that the eurozone maintains a large surplus vis-à-vis the UK and that it is difficult to gauge the extent to which such a large imbalance will be maintained in the event of Brexit.

Costs of relying heavily on external demand

This pattern of export-driven growth is not necessarily a problem. Domestic demand can take the place of exports when the latter falter. Moreover, a strong propensity to save may pave the way towards stronger investment performance in the medium to longer run. As well, European countries may have a strong preference for under-spending and to invest their surplus savings abroad. Such a strategy can prove an effective way of sustaining future living standards.

However, these justifications for the export-driven model are not supported by the facts. First, as already mentioned, recent trends show domestic demand is not responding in the face of declining exports.

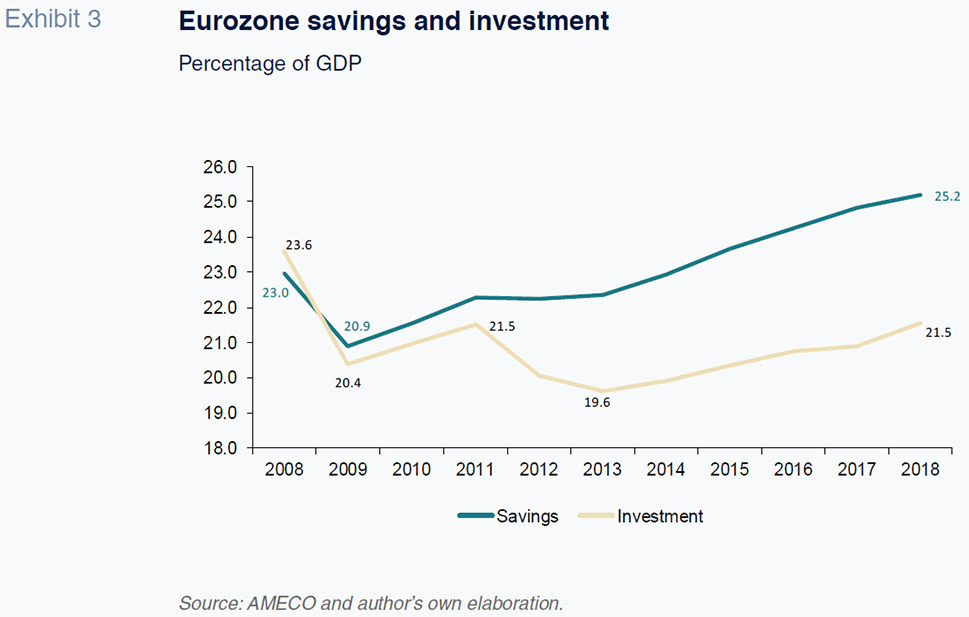

Second, and more fundamentally, subdued domestic demand reflects both a rising propensity to save and limited investment growth in the eurozone (Exhibit 3). National savings (which include both private and public savings) have increased uninterruptedly since their trough of 2009. In fact, they have reached over one quarter of national income, an all-time high and an impressive savings effort by international standards. By contrast, investment trended downward until the trough of 2013, before moderately increasing. As a proportion of GDP, eurozone investment has reached 21.5%, well below pre-crisis levels. This is concerning given the dearth of investment in eurozone countries, including Germany, which has underinvested in its infrastructure. For Europe as a whole, higher investment is necessary for a successful transition to the green economy and to reap the benefits of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Thus, the growing external surplus reflects the fact that Europe is less able to mobilize its savings to invest in its real economy. The result is that it must export its lending capacity to other countries.

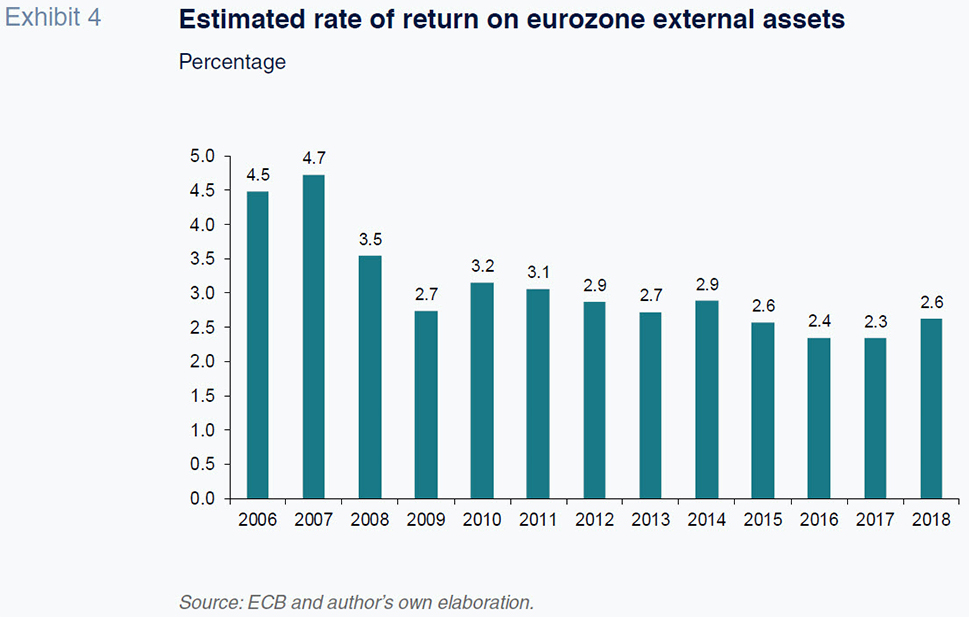

Third, it could be argued that the investment opportunities in Europe are less attractive than those arising in other parts of the world. However, there is no clear evidence in support of this assertion. Indeed, the revenues generated from eurozone external assets are declining and may be even lower than the rate of return on equivalent investments in Europe.

Between 2007 and 2018, total assets accumulated abroad by eurozone countries nearly doubled from 12.5 to 26.5 trillion euros. This significant increase can be explained by the accumulation of current account surpluses, adjusted for any appreciation or depreciation effects arising from exchange rate movements and other valuation factors. During the same period, the income gains arising from assets invested abroad increased by just 16%, from 0.6 to 0.7 trillion euros. In other words, the rate of return on external assets has nearly halved (Exhibit 4).

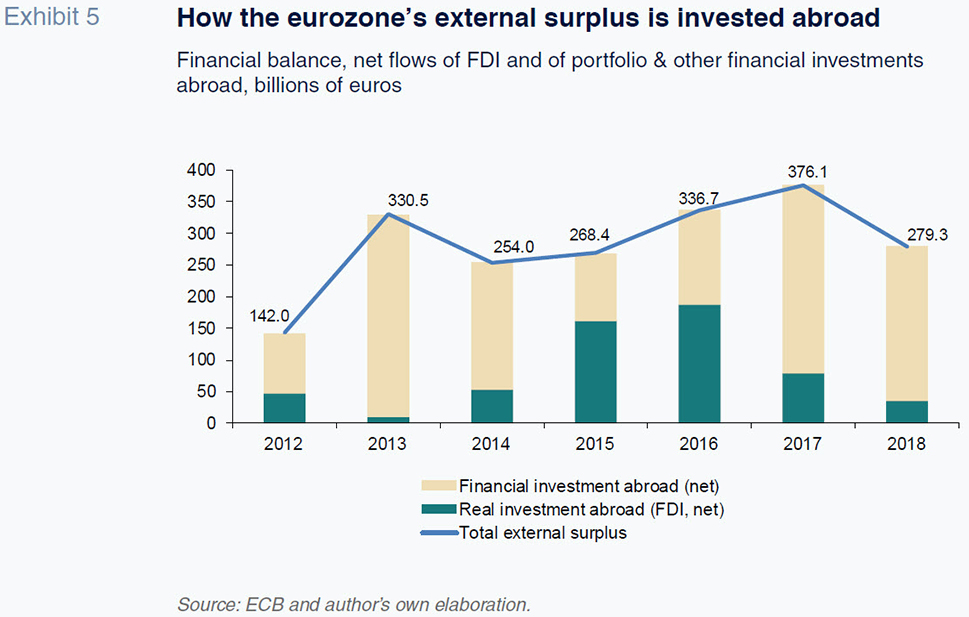

At 2.6%, the rate of return on external assets is not only relatively low (especially considering the profits that can be made in Europe) but is also subject to significant uncertainty. Indeed, roughly two-thirds of external assets are portfolio investments and other financial positions whose value and returns are subject to sudden swings in the external environment. The remaining one-third is composed of foreign direct investment, which generally offers more stable returns than investments in financial assets. Exhibit 5 shows the pattern of current account surpluses invested abroad and highlights the prevalence of financial investment over real investment.

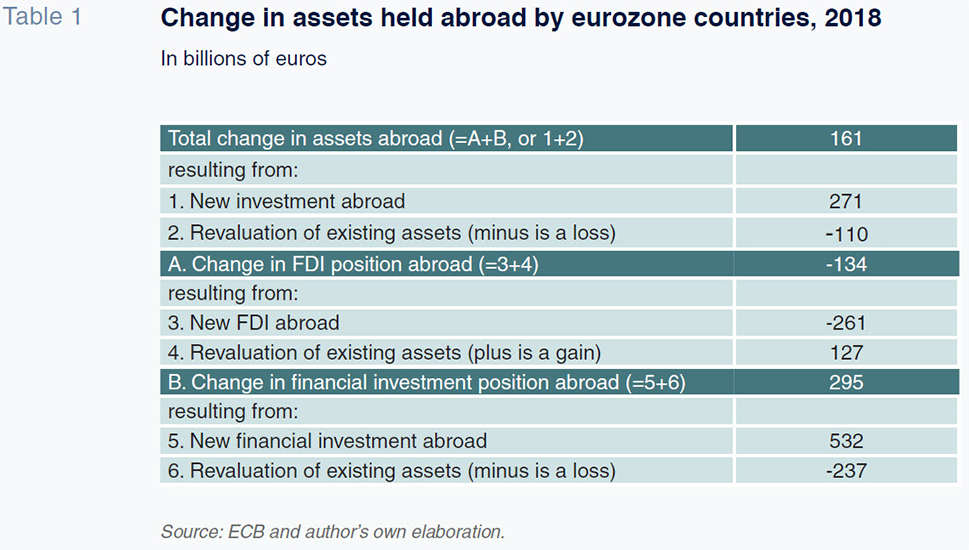

Table 1 provides further details on how external financial investment positions can be subject to significant market losses, especially when compared to foreign direct investment.

[3] In 2018, around 237 billion euros were lost due to exchange rate changes or other price shifts. This compares to a gain of 127 billion euros in the case of foreign direct investment.

In short, the net lending position of the eurozone has only partly provided stable, future income gains.

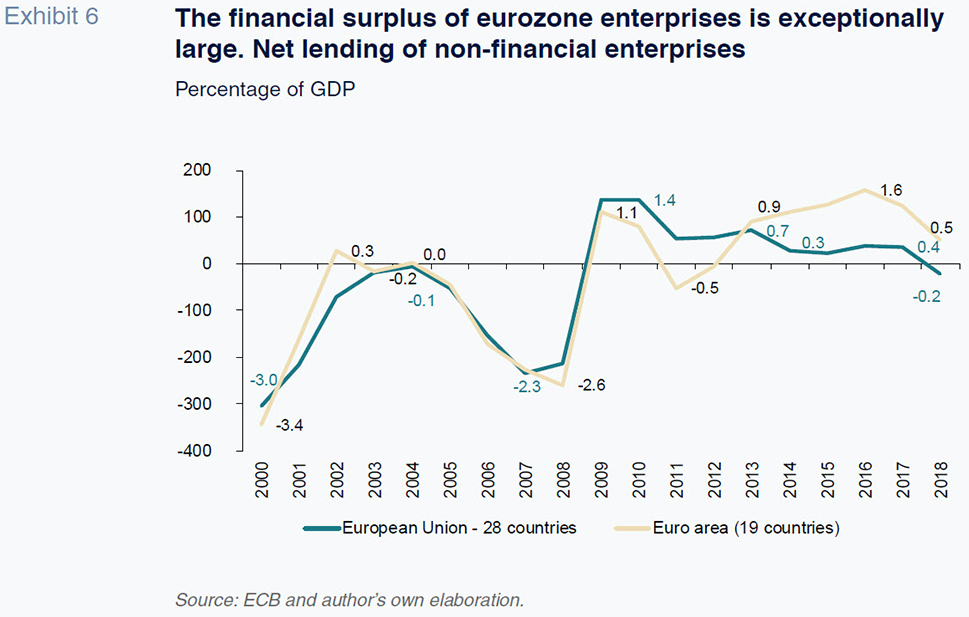

[4] Much of the external surplus seems to be motivated by lack of sufficient investment opportunities in Europe, rather than low profitability. Indeed, enterprise profits remain comfortably high and exceed investment spending to the point of generating a sizeable net lending capacity for the enterprise sector as a whole (Exhibit 6). Under normal circumstances, businesses borrow to modernize existing capital or expand. Overall, these data highlight the role of the downward bias in internal demand, which has trended across the eurozone.

Role of macroeconomic policies in rebalancing the economy

An in-depth investigation of the origins of the downward demand bias goes beyond the scope of this paper. However, it is helpful to discuss the key role that macroeconomic policies play in this regard.

In essence, the arrangements that govern participation in the single currency may depress demand by pushing countries towards policies that aggravate the impact of recessions and limit the benefits of expansions. This pro-cyclical pattern tends to dampen long-term performance (Torres, 2018).

To illustrate this point, it is helpful to consider two peculiarities of the eurozone. First, national governments cannot rely directly on their domestic central banks as a lender of last resort. They benefit indirectly through any purchases of government paper in secondary markets by the ECB, but this is subject to certain conditions, which in practice make governments prone to engaging in pro-cyclical fiscal policy.

Secondly, the eurozone lacks an adequate fiscal capacity to supplement individual countries in their limited attempts to offset the effects of the business cycle. If a country is disproportionately affected by an economic shock, it is possible to access crisis-management funds. However, these are subject to strict criteria and implementation delays. Moreover, a stigma is attached to these funds, which in practice makes governments hesitant to use them.

Due to the limitations of fiscal policy, monetary policy has, to some extent, acted as a counter-cyclical device. The ECB has developed a set of heterodox tools —a combination of record low interest rates, purchases of government bonds and support to bank loans— which in the past proved effective in tackling deflationary pressures. There is also evidence that such a heterodox policy has eased financial conditions in Europe, thus supporting the economy (Alcaraz et al., 2019).

This policy, however, is losing effectiveness.

[5] First, the ECB strategy may face technical constraints, especially relating to the asset purchase programme. The ECB acquires new government bonds as old ones come to maturity, with a view to keeping the total value of bonds constant. This reinvestment policy will be maintained for a prolonged period. The ECB may even consider increasing its net purchases in the near future. However, the task is increasingly difficult thanks to the downward trend in public deficits across the eurozone, which has reduced the supply of available bonds. Record low borrowing costs are evidence of this shortage of sovereign debt.

[6] For instance, the Spanish government is able to sell 10-year bonds at an interest rate below 0.3%, which is the lowest in the history of the country, and in Germany the interest rate has entered negative territory.

[7]

Second, in the absence of other drivers of growth, prolonged monetary stimulus may end up reaching the wrong target. In some cases, the measures may serve to support “zombie” enterprises, which only survive thanks to the availability of cheap credit. By contrast, monetary policies may do little to reallocate resources to frontier enterprises or innovative investments.

Third, monetary policy cannot tackle cross-country divergences, as illustrated by the case of Italy. The Italian economy has stagnated since the launch of the euro, leading to a historic decline in living standards. Moreover, business investment has been hit, thereby compromising long-term prospects. Already, productivity levels are lower than in competing economies. There is a low-growth trap at work, as the bleak economic prospects not only affect investment but also push young, talented Italians to migrate. This aggravates demographic decline, further depressing future prospects. Markets are aware of these dynamics and request a higher premium for their purchases of Italian bonds, putting additional pressure on the Italian economy.

Italy’s ability to move out of this trap is limited. Despite the accommodating stance of the ECB, borrowing rates for Italian businesses and households remain relatively high. But policies that may benefit Italy would not fit with the circumstances of the majority of other eurozone economies, and are therefore highly unlikely. Fiscal policy is also constrained by prevailing rules. Furthermore, its effectiveness is limited by the fact that interest rates exceed the expected rate of return on investment. (Italy is one of the few European economies where the return on government bonds is higher than the economy’s potential rate of growth.)

Unfortunately, few additional instruments remain. Reforms are needed urgently, notably with respect to non-performing loans, which continue to plague banks. However, any reforms will take time to implement and boost economic growth.

Thus, monetary policy alone can neither solve the excess savings problem, which presently characterises the eurozone, nor tackle cross-country divergences.

Conclusion

Europe’s growth model, with its heavy reliance of exports to compensate for the chronic shortage of domestic growth, is being called into question. This is partly due to the global geo-political tensions and the deterioration of the external environment. A less obvious reason is the significant excess savings position of the eurozone. Specifically, there are around 300 billion euros of savings invested in the rest of the world, with increasingly unpredictable returns. Overall, these findings call for a revaluation of the macroeconomic policy stance of the eurozone, along with a strengthening of its architecture.

Notes

The author is grateful to Romain Charalambos for his very helpful research assistance.

For a detailed examination of trade policy trends, see Begg (2019).

This peculiarity was previously highlighted by Darvas and Hüttl (2017).

An early investigation of this problem can be found in Wajda-Lichy (2015).

This discussion draws on Torres (2019).

For a detailed discussion of the supply and demand situation in European bond markets, see Carrión (2019).

The only exception to this pattern is Italy, but this is a reflection of heightened country-specific risks.

References

ALCARAZ, C., CLAESSENS, S., CUADRA, G., MARQUES-IBAÑEZ, D. and SAPRIZA, H. (2019). Whatever it takes: what’s the impact of major nonconventional monetary policy intervention?

ECB Working Papers, Number 2249, March.

BEGG, I. (2019).

Trade policy at a turning-point. Funcas Europe. July. Retrievale from:

www.funcas.es/funcaseuropeCARRIÓN, M. (2019).

The financial challenges facing the EMU. Funcas Europe. June. Retrievale from:

www.funcas.es/funcaseuropeDARVAS, Z. and HÜTTL, P. (2017). Returns on foreign assets and liabilities: exorbitant privileges and stabilizing adjustments.

Bruegel Working Paper, Issue 07, November.

ECB (2019).

Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area. 2019. Retrievable from:

www.ecb.europa.euTORRES, R. (2018). European fiscal policy: Situation and reform prospects.

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, Volume 7, number 5, September. Retrievable from:

www.sefo.funcas.es— (2019).

ECB moving into new territory. Funcas Europe. June. Retrievale from:

www.funcas.es/funcaseurope WAJDA-LICHY, M. (2015). Excessive current account surpluses in euro zone economies – problem of particular economies or the euro area as a whole?

Journal of International Studies, Vol. 8, No 3, pp. 99-111.

Raymond Torres. Director for Macroeconomic and International Analysis, Funcas