Translating EURIBOR increases into improved banking margins: Differential timing on asset and liability repricing

After more than five years of abnormally low, even negative, interest rate levels in the case of the 12-month EURIBOR, the fact that rates have turned positive and look likely to stay there on a structural basis foreshadows a clearcut improvement in the banking sector’s net interest income. Irrespective of the clearly positive impact of the new rate scenario for the banks, the transition will not be linear and before margins increase, they will likely dip.

Abstract: The historical evidence-backed convention indicates that the banks’ net interest margin gets squeezed far more during times of low rates, and certainly during periods of zero or negative rates, as has been the case in the eurozone for more than five years. By this logic, the Spanish and European banks’ margins should improve within the context of the new, positive interest rate environment. The most important curve for the retail banking business is 12-month EURIBOR, which is currently trading firmly in positive territory, after more than five years in negative terrain. However, rate increases will not translate into higher net interest income (NII) in a linear fashion. In fact, it is highly probable that we will see the banks’ income etch out a sort of J-curve, with margins actually dipping before recovering and heading decisively north. The reason for this is the different pace and intensity of bank asset and liability repricing in response to the new EURIBOR curve. Indeed, the pace of repricing is slower in the case of floating mortgages (an asset category of significance for the Spanish banking system), giving rise to the initial effect of contracting margins prior to a gradual recovery ahead of moving into clear positive territory.

Sharp rebound in EURIBOR following five years in negative territory

The most relevant interest rate for the retail banking business, EURIBOR, particularly the 12-month rate, has been in negative territory for more than five years, exerting strong downward pressure on net interest margins, sandwiched between assets on which returns kept heading lower and lower and, on the liabilities side, deposits on which it was practically impossible to apply negative rates, other than wholesale funding tied to EURIBOR.

In recent months, this situation has changed radically as inflation has spiralled, fuelled, initially by the bottlenecks arising as the world emerged from the pandemic, then by the invasion of Ukraine, and lastly, by the burgeoning risk of second-round effects, prompting the central banks to tighten their monetary policies far faster and more forcefully in the case of the Federal Reserve and much more gradually in the case of the European Central Bank.

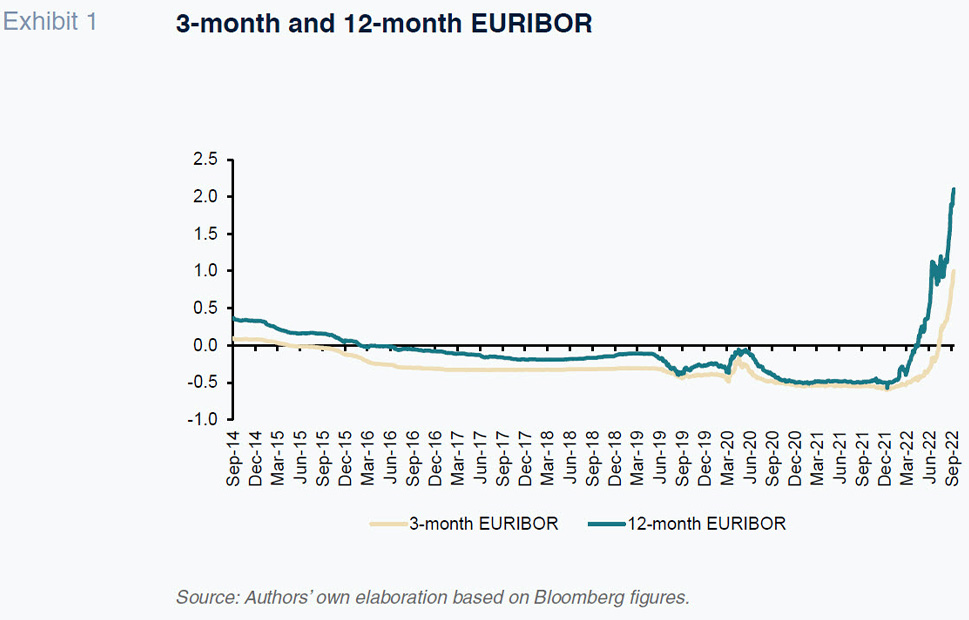

Despite the ECB’s ‘wait-and-see’ approach, the markets began to price in the shift in rate scenarios several months ago. As shown in Exhibit 1, benchmark rates began to climb higher last December, a trend that has gathered speed during the first few months of 2022, particularly since March, shortly after the armed conflict broke out, driving energy prices sharply higher and fuelling inflation in the process.

Given the radical change in the interest-rate scenario, it is timely to analyse the likely trend in the Spanish banks’ net interest income in both a structural context characterised by clearly positive rates, and during the transition to that scenario, particularly in light of the extraordinary volatility that has marked the rebound in rates and the differing sensitivities thereto of assets and liabilities.

From a structural standpoint, it is fairly obvious that the banks’ net interest income is directly correlated to interest rate levels. The main reason is the existence of a large stock of sight deposits that earns little or no income, which is not enough to compensate for the drop in financial income when rates fall to or below zero but does buffer interest income when rates are high.

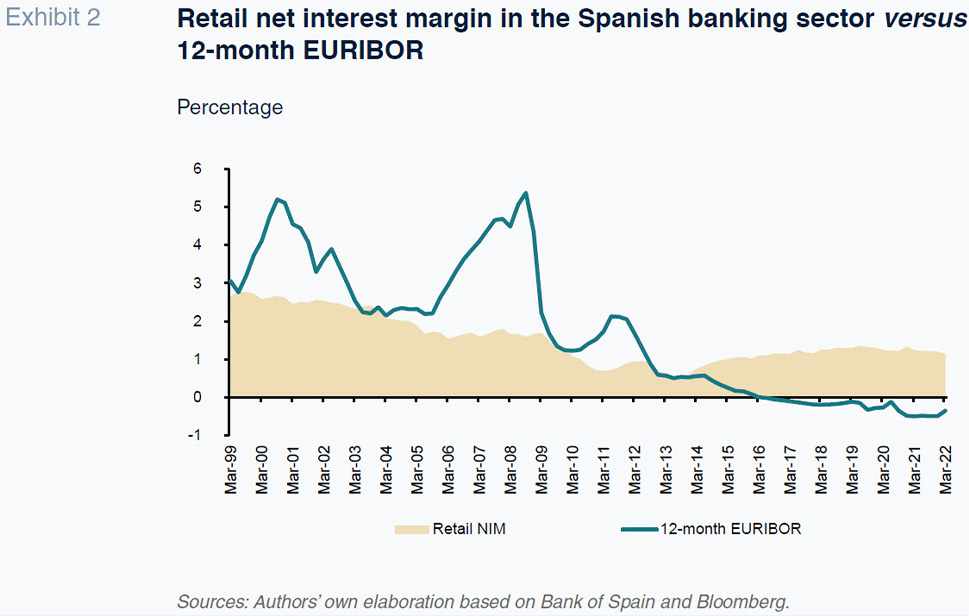

That direct correlation between the margin and rate levels is corroborated by the margins reported by the Spanish banking system since the single currency was created at the start of 1999. Exhibit 2 plots the long-term trend in NIM against the trend in 12-month EURIBOR. Leaving the short-term volatility aside, the change in NIM when the market moves into a positive EURIBOR scenario is clear: at such times, the margin moves between 1% and 2%, compared to a scant 1% when EURIBOR heads towards or below zero.

That structural correlation suggests, therefore, that in the new rate environment, in which EURIBOR looks to be headed towards a cruising level of around 2.5% (the level which the futures market views for 12-month EURIBOR for the next three to four years), the Spanish banks should see their net interest income rise considerably.

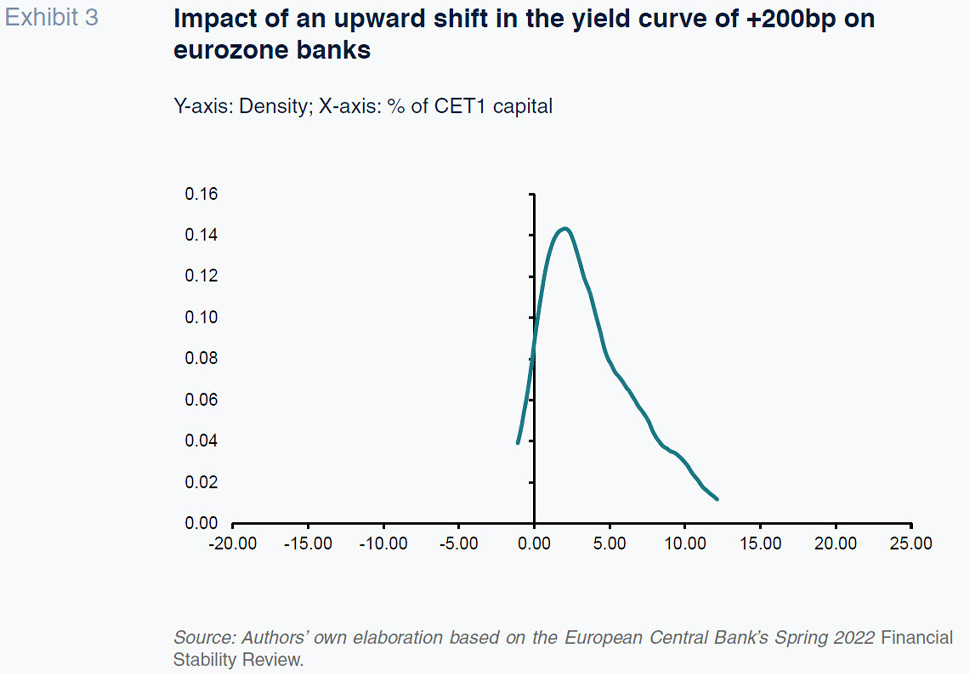

The potential favourable impact of the positive rate environment on net interest income was estimated by the European Central Bank itself in its last Financial Stability Review. Specifically, the ECB estimates that a parallel shift in the curve of +200bp could generate an increase in earnings (NII) as a percentage of the banks’ capital of between 2 and 5 percentage points for a broad sample of European entities. Here it is worth noting that in the case of the Spanish banks, that impact could be even greater given that floating rates represent a higher weight of transactions relative to the European average.

NII during the transition phase: Differential timing of asset and liability repricing

Irrespective of the potential positive impact on NII in the new rate scenario, the transition to such a scenario is not likely to be linear given the rapidity with which the change in rate expectations has taken place and the different sensitivities of banking assets and liabilities to the new rates.

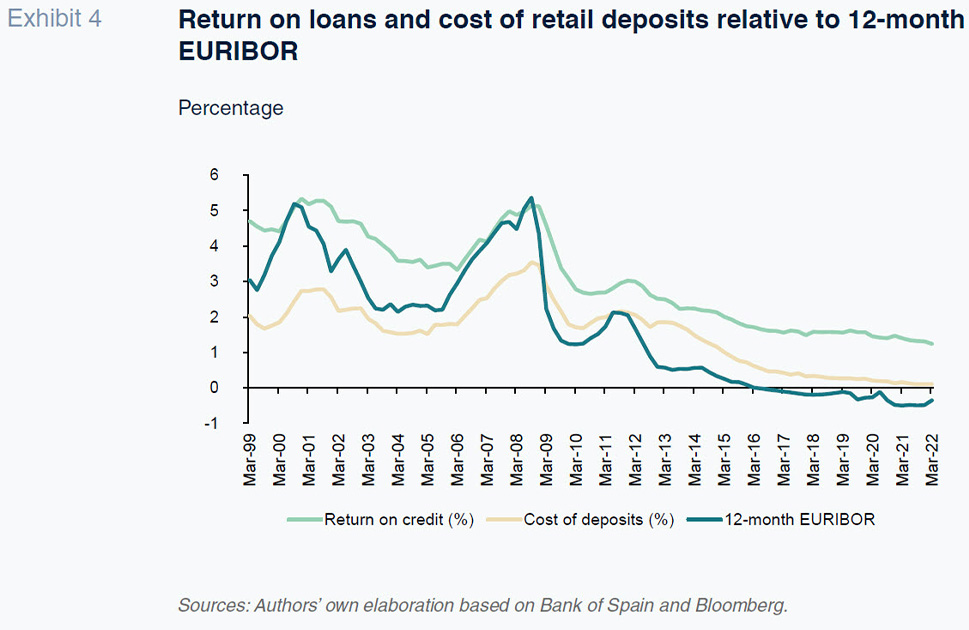

The first step in our analysis of those sensitivities was to look at the historical trend in both components of retail banking interest income (return on credit, or investments, and the cost of retail funding, or deposits) and their correlation with 12-month EURIBOR since the creation of that benchmark index, in conjunction with the introduction of the euro.

That analysis yields two very interesting conclusions with respect to the possible outlook for the banks’ interest income. Firstly, the EURIBOR sensitivity coefficient is substantially higher in the case of investment returns (0.72) than in the cost of deposits (0.47), further corroborating the favourable impact of a high-rate environment on margins. However, the analysis also reveals how the response to sudden changes in EURIBOR is far slower in the case of loan income relative to the cost of deposits.

The slower incorporation of increases (and decreases) in EURIBOR into the return on the banks’ credit has to do with the existence of long-term loans at fixed rates of interest, essentially fixed-rate mortgages. In Spain, fixed-rate mortgages have a relatively short history. The banks have only been marketing them on a widespread basis since 2020, nonetheless, they account for just under 25% of all outstanding mortgage credit, according to the Bank of Spain.

The other reason why there is a lag in seeing the increase in 12-month EURIBOR trickle through to the banks’ interest income is the timing with which floating-rate loans, essentially mortgages, get repriced. Those loans, with an outstanding balance of 375 billion euros at year-end 2021, represent the largest segment of the Spanish banks’ loan portfolio and their repricing dynamics are key determinants of the trend in the banks’ interest income. While a trickle of loans may still be benchmarked to other indices, the vast majority of floating-rate mortgages are benchmarked to 12-month EURIBOR, and are repriced annually, on the basis of the average EURIBOR rate during the month prior to the repricing event.

Based on that repricing regime, and assuming that the price resets take place evenly over the course of the year (a fairly reasonable assumption, perhaps with the exception of August when new lending tends to dip), the transfer of the increase in EURIBOR to interest income will take place on a staggered basis over a 12-month period, so that the banks will not benefit from the full effect of the repricing phenomenon until the end of that period.

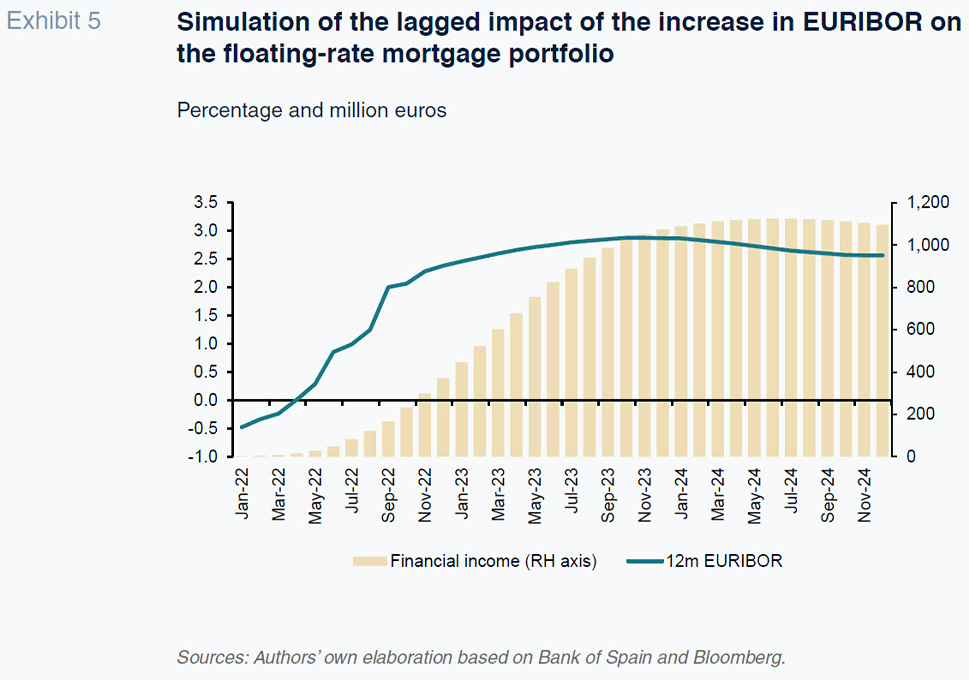

To illustrate the effect of that time lag, below we simulate the timing of the increase in interest income under that repricing regime, assuming, moreover, that 12-month EURIBOR actually performs as is currently being discounted by the futures market (refer to Exhibit 5). That same exhibit depicts the trend in incremental monthly interest income as a result of the repricing dynamic, using the monthly average observed in 2021, before EURIBOR embarked on its upward path, as the basis of comparison.

That simulation illustrates how the new rate scenario, assuming 12-month EURIBOR around 2.5% discounted by the market, will translate into growth in monthly interest income of around €1,000 million more compared to what the banks were making when EURIBOR was at -0.5%. However, achieving the full benefits of the new rate scenario will take almost 12 months from when EURIBOR reaches those expected levels of 2.5%, with income rising very gradually during the transition to that ceiling.

Conclusions

After more than five years of abnormally low –negative– interest rate levels in the case of the most important benchmark index for the banking business (12-month EURIBOR), the fact that rates have turned positive and look likely to stay there on a structural basis foreshadows a clearcut improvement in the banking sector’s net interest income. The historical evidence since that benchmark index came into existence indicates that interest income is far more sensitive to rate changes than interest expense.

Irrespective of the clearly positive impact of the new rate environment for the banks’ net interest income, the transition will not be linear and before the margin increases it is likely it will dip. The reason lies with the staggered incorporation of the rebound in EURIBOR in the core loan segment for the Spanish banking system –floating-rate mortgages– where the impact of the rate increase arrives with a one-year lag. That lag is greater the quicker the rise in rates takes place (the current shift in expectations has come about particularly swiftly – around 2.5 percentage points in just nine months).

That J-curve effect in net interest income (initial decline followed by clearcut recovery) is already materialising in the first quarters of 2022, judging by the earnings reported by the biggest Spanish banks, whose net interest income declined by 4% year-on-year in the first quarter and by 2% in the second quarter. In the coming quarters, it is likely that the year-on-year contractions in NII will gradually slow before moving on to sustain growth throughout 2023, when the bulk of the assets subject to repricing will already feature EURIBOR of around 1% or higher, depending on when the repricing took place.

References

ECB (2022). Financial Stability Review, May.

HERNÁNDEZ DE COS, P. (2022). The Spanish banking industry and the economic challenges ahead, June.

Marta Alberni, Ángel Berges and María Rodríguez. A.F.I. – Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.