Spain’s fiscal consolidation path: Slow but steady

After several upward revisions to original targets, the Spanish general government complied with EU deficit targets for 2016. Analysts are largely optimistic that the 2017 targets will be met, but not without challenges.

Abstract: Following several upward adjustments by the EU to the original 2016 deficit targets, the Spanish government (all levels) closed 2016 with a public deficit of 4.3% of GDP (excluding aid to the financial system), or below the 4.6% of GDP official objective. Target compliance was achieved with the help of the surplus recorded at the local government level, which compensated for slippage by Social Security and the slowdown in consolidation at the central government level. Consensus among most analysts is that Spain will come close to reaching the deficit target of 3.1% of GDP for this year, albeit the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (AIRef) has been more cautious. Optimism is underpinned by the notable acceleration of Spanish GDP growth, which has outperformed expectations, together with the outstanding scope for some discretionary spending cuts at the central government level in the event of 2017 targets coming under pressure. In any case, the latest April version of the 2017-2020 Stability Plan presents three relevant takeaways regarding Spain’s fiscal consolidation path: i) the effort will come 80% from expenditure adjustment and 20% from revenues; ii) progress remains systematically slow and the current level of structural deficit needs to be further reduced; and, iii) spending cuts must be taken carefully if to avoid a scenario where the quality of Spain’s public services falls below that of its peers.

Introduction: Where are we coming from? [1]

The Spanish government (all levels) ended 2016 with a public deficit of 4.3% of GDP (4.5% if we include the aid extended to the financial system), implying delivery of the then-prevailing deficit target (4.6%). Recall, however, that that target had been revised upwards twice over the course of 2016 in order to adjust to the reality being revealed by the monthly and quarterly reports (Lago-Peñas, 2017). Indeed, the deficit target was initially set at 2.8% (September 2015), raised to 3.6% in April 2016 and raised again to the above-mentioned 4.6% in August.

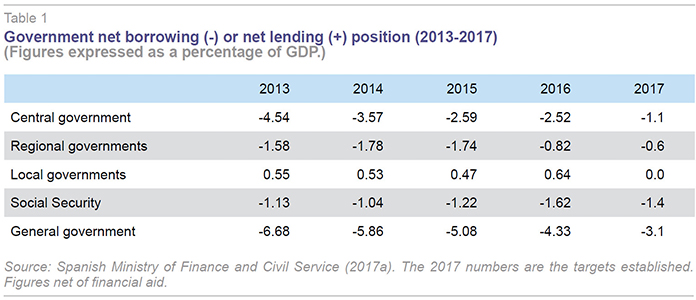

Table 1 shows government net borrowing (-) or lending (+) figures for each of its four sub-sectors for the last year of the crisis (2013) and during the following three years of recovery (2014-2016), additionally presenting the targets for the year in progress. The reduction in the deficit has been steady but slow in light of the considerable improvement observed in the output gap in the interim

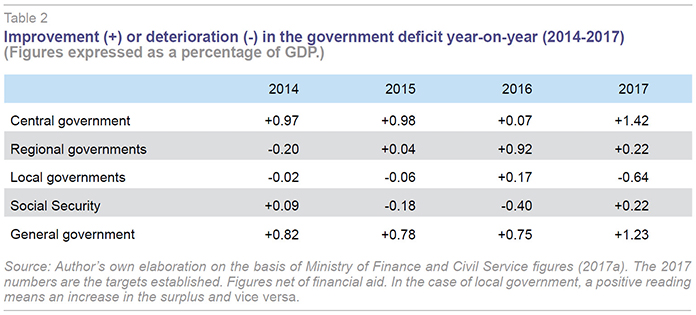

[2]. In fact, more granular analysis of the trend by sub-sectors heightens the concern over the consolidation difficulties observed. Table 2, meanwhile, complements the information provided in Table 1 by showing the annual changes in the various balances between 2014 and 2017.

The significant and systematic surpluses at the local government level have the effect of sweetening the overall snapshot. While required to target a balanced budget, the local governments have ended up compensating for the target misses by the rest of the levels of government. Their performance is attributable to a sharp correction in so-called ‘non-mandatory’ spending by local governments in areas not strictly within their realm of authority and higher tax income forced by tax rate increases imposed under state law.

The Social Security lies at the other extreme of the spectrum. Despite the clear-cut improvement in labour market indicators, which should drive revenue growth via social security contributions, coupled with the measures taken to curb the growth in pension costs, the deficit has been rising consistently. Depletion of the Social Security’s reserve fund appears inevitable and imminent and warrants the urgent passage of measures to complement the protection afforded by the so-called Toledo Pact

[3].

Thirdly, the regional governments as a whole demonstrated an apparent inability to bring their deficits below 1.5% of GDP in 2014 and 2015. However, this inability was closely related to the regional government financing system. In essence, it pivots around streams of advance payments and payments on account calculated and granted by the central government. If the central government’s forecasts are overly optimistic, the regional governments are transferred more than they really should receive. And if the forecasts fall short of the mark, the opposite happens. When these prepayments are definitively settled two years later (i.e., the provisional 2014 amounts are settled in 2016) a series of grants take place which can be positive or negative (money returned by the regional governments to the state). Between 2008 and 2009, the advance payments and payments on account were much higher than what was really due in light of the collapse in tax revenue in Spain, thus falsely delaying the need for fiscal austerity by most regional governments. In contrast, in 2014 and 2015, the central government’s forecasts fell short, so that the regional governments’ revenue failed to reflect the economic uptick and their deficits did not fall. Settlement of the 2014 amounts, which the regional governments received in 2016, was very favourable for the latter. And that is the main factor justifying the substantial improvement observed in the regional government deficit, which dropped from 1.74% to 0.82%, that year. Indeed, the surplus settlements accounted for over three-quarters of the fiscal consolidation progress made (Lago-Peñas, 2017).

Lastly, the progress made at the central government level slowed in 2016. Having managed to cut its deficit at an annual pace of 1% in 2014 and 2015, the improvement slowed in 2016, a trend that is largely the flip side of the coin of the deficit-cutting at the regional level.

Deficit consolidation in 2017: Outlook for target compliance

To assess the prospects for deficit reduction in 2017, the first thing to consider is the current target and the amount by which the deficit accordingly needs to be cut year-on-year. Looking at Table 2, the government expects to reduce the budget deficit by 1.23 percentage points of GDP, with most of this improvement expected at the central government level. The central government deficit is forecast to drop by 1.42 points, compared to just 0.22 points at the regional government level and a reduction of a similar size in the case of the Social Security. Accordingly, the overall deficit reduction would be substantially bigger than that registered between 2014 and 2016, when it was cut by between 0.7 and 0.8 points annually. Moreover, the starting point is less favourable than it might appear. Here the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (AIRef) (2017a) delves beyond the distinction between whether or not the deficit target includes the financial system aid to allude to one-off transactions (particularly the impact of the regulatory changes to the tax prepayments approved by the central government), which in 2016 had a positive impact at the aggregate level. Stripping out these one-offs, the overall deficit would have ended 2016 at 4.5%, implying the need to cut the deficit by 1.4 percentage points in 2017, which is virtually double the annual improvement achieved between 2014 and 2016.

The consensus among analysts is that Spain will come in very close to its target this year. The consensus among the analysts reporting to Funcas as of July 2017 points to a deficit of 3.2%. Of the 16 institutions included in the average for this variable tracked by Funcas, nine are forecasting a deficit of 3.1%, with none estimating a better result. Current official forecasts point in the same direction. The European Commission and the Bank of Spain (in a report dated June 13th) are forecasting a deficit of 3.2%; the IMF is anticipating 3.3% and the OECD’s forecasts point to 3.4%. And the trend of late is one of favourable revisions to these forecasts in light of the unfolding growth, which is topping even the most optimistic expectations, at least in the first half of 2017.

The AIReF, however, is more cautious: its most recent forecasts call for a higher deficit. At the end of April (AIReF, 2017a), it saw the overall target of 3.1% as ‘feasible albeit challenging’, assigning a probability of a target miss of 50%. However, in June it changed its prognosis to ‘improbable’, based on its consideration that the probability of a target miss had increased to 60% (AIReF, 2017b). The main reason for this turn of events is the impact of the state damages liability clause that would be triggered in the event that the Ministry of Public Works bails out eight bankrupt toll roads at a cost estimated at 0.2% of GDP. Without this one-off development, the outlook would remain ‘feasible albeit challenging’.

This divergent prognosis, depending on whether or not a development that is one-off yet significant financially is included, generates a distortion that is not easy to address. If factored in, the cyclical deficit does not faithfully represent the structural fiscal consolidation efforts being made. If omitted, however, the impact of the deficit on the national debt is underestimated; moreover, its omission may give the general public the idea that these targets are ultimately flexible in terms of size and definition, which is detrimental to trying to build a sense of collective responsibility on the fiscal front. Observation of the structural rather than the cyclical deficit would go a long way to solving these problems but runs up against the technical difficulty of estimating this component of the deficit accurately and robustly.

Deficit consolidation in 2017: What do the settlement figures tell us so far?

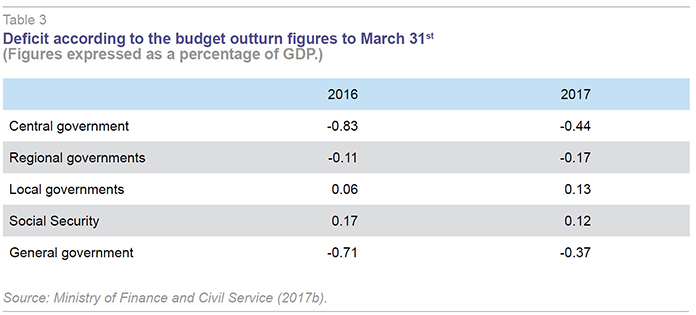

Table 3 summarises the trend in the public deficit during the first quarter of 2016 and 2017. For the government as a whole, the figures point to a significant reduction in the deficit (slightly above 0.3 percentage points of GDP), most of which attributable to the central government, whose accumulated deficit fell from -0.83% to -0.44%. Projecting this reduction for the year as a whole, and assuming a symmetric trend in revenue and expenditures with respect to 2016, the targeted reduction of 1.23 percentage points would be met. However, the symmetry assumption is somewhat extreme, making it necessary to examine potential shifts in revenue and spending patterns. To this end, the new data added by the AIReF to its website under the heading Tracking the Stability Target are particularly useful.

In the case of the regional governments, the budget outturn figures to March 31st and their extrapolation are favourable. Good momentum in revenue and a degree of offsetting between growth in current spending and slower investment execution have changed the outlook for compliance with the target for 2017 (a deficit of 0.6% of GDP) from ‘feasible’ to ‘probable’.

Secondly, the problems affecting the Social Security are concentrated on the revenue side of the equation, specifically social contributions, in which growth continues to lag nominal GDP growth. The data available to date make it highly likely that the Social Security’s expense targets will be met, thanks largely to the reduction in the outlay for unemployment benefits, but very improbable that the revenue forecasts will be delivered. The numbers point to a deficit in 2017 of 1.6%, 0.2 points above target and very close to last year’s observed figure.

Lastly, the central government, which faces the steepest deficit-cutting challenge, poses the most doubts. Revenue is trailing the government’s forecasts and nominal GDP growth. Based on the first-quarter numbers, the shortfall with respect to targeted revenue is attributable to lower than forecast receipts from personal income tax and special duties. In contrast, revenue from VAT and corporate income tax is faring better than forecast, albeit not by enough to offset the underperformance in the former two taxes; here, delivery of the goals for the year is feasible. On the spending side, things are relatively better, although, as mentioned earlier, the impact of the state liability for the bankrupt toll roads has added more pressure. If we additionally factor in the likely impact of the change in the amounts to be transferred to the Basque region, the AIReF views the likelihood of delivery of the deficit target as ‘improbable’ (probability of a miss of 80%).

That being said, there are at least two reasons for greater optimism regarding the prospects for complying with the overall deficit target for 2017. The first, already alluded to, is the fact that economic growth is accelerating once again and it is highly probable that GDP growth will once again approach or even surpass the 3% mark in 2017. Whereas the 2017 state budget assumed real GDP growth of 2.5%, the Bank of Spain is currently forecasting 3.1% (in its June macroeconomic projections), while Funcas consensus forecast stands at 3.1% (forecasts published in July). Although tax revenue and Social Security contributions are proving less elastic to nominal GDP growth than anticipated, this growth should nevertheless accelerate tax collection significantly.

Secondly, the government has room to approve additional measures to help balance its books. In fact, not all the initiatives contemplated in the packet of fiscal measures designed for the rollover of the 2016 budget have been set in motion and transferred to the 2017 budget

[4]. Specifically, the update to the 2017-2020 Stability Plan (Ministry of Finance and Civil Service, 2017a) states that: “If over the course of the year the budget outturn numbers were to evidence a risk of falling short of the target, the measures already committed to would be implemented[…], specifically environmental taxes and the tax on sugary drinks, which would raise 300 million and 200 million euros, respectively”. Those additional 500 million euros would create a buffer of approximately 0.4 points of GDP.

In short, unforeseen difficulties have cropped up in the fiscal consolidation path this year and first-quarter revenue has fallen short of expectations. Balancing this out, however, Spanish GDP growth is accelerating notably, surprising private and public analysts alike. Meanwhile, the central government still has some discretionary power if it needs to redirect deviations that are jeopardising the target set for 2017.

Beyond 2017: The 2017-2020 Stability Plan

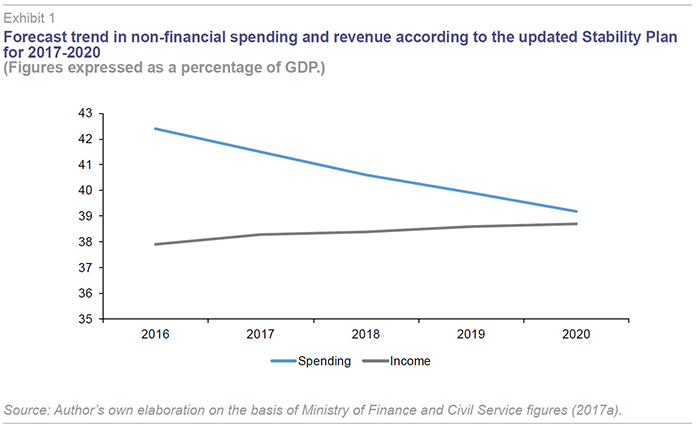

At the end of April, the central government presented the updated version of its Stability Plan for 2017-2020. Exhibit 1 depicts the three key prongs of this strategy: non-financial spending, non-financial income and the gap between the two, the deficit. The values are expressed in terms of GDP. The three main conclusions are as follows:

- The consolidation effort is focused on the spending side of the equation. Underpinned by annual nominal average GDP growth rate of 4.2%, the Plan designs a roadmap for cutting spending over GDP by 3.2 percentage points between 2016 and 2020, such that nominal spending would rise at just above 2% per annum (2.2%). Revenue is projected to stay broadly stable, increasing 0.8 percentage points of GDP over the same period. This means that the deficit-cutting effort will be driven 80% by spending cuts and just 20% by income growth. This pattern of consolidation has been the rule in fiscal strategy since the Partido Popular’s first administration (Lago, 2014).

- Despite the fact that the economic climate has been on the side of fiscal consolidation since 2014, delivery of the original deficit-cutting targets has been systematically and successfully pushed back in time. When the Stability Plan was updated for 2014-2017, the goal was to cross the 3% threshold in 2016 (2.8%) and go on to post a deficit of 1.1% in 2017 (Lago, 2014). In the most recent update to the Plan for 2017-2020, the target for 2017 remains above the 3% mark, falling to 1.3% only in 2019. Considering the fact that the government expects to register a positive output gap once again this year (+0.60%), the numbers imply the maintenance of a structural deficit of close to 1.5%. A level that appears high if the government wants to retain room for manoeuvre in the fiscal policy arena against the backdrop of European stability. Excessive too if the goal is to drive the current stock of public debt down towards 60% of GDP within a reasonable timeframe.

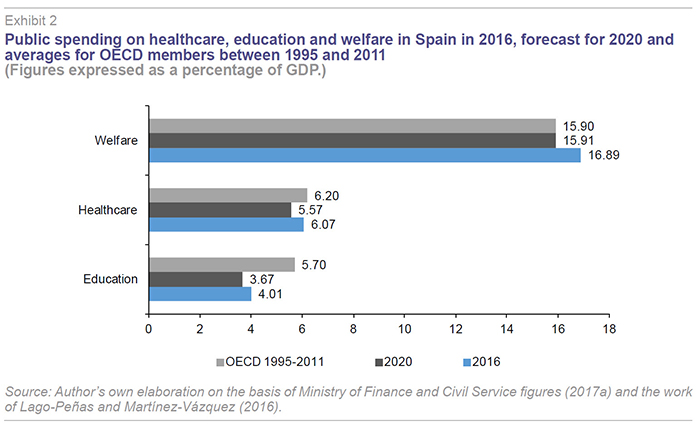

- The public spending cuts of the past and the additional austerity foreseen (very limited nominal growth and significant drop in the ratio of public spending to GDP) will translate into challenging public budgeting restrictions. Analysis of the expenditure breakdown reveals that the weight of public spending declines in all categories. Exhibit 2 illustrates three of the most important areas quantitatively: welfare (including pensions and unemployment benefits), healthcare and education. It provides figures as a percentage of GDP in 2016 and 2020 alongside the average for OECD members between 1995 and 2011, as calculated by Lago and Martínez-Vázquez (2016). On a relative basis, the forecast adjustment will be more pronounced in healthcare and education, areas delegated in the regional governments. And education will be particularly hard hit.

Barring changes in the areas targeted for consolidation, it is clear that the efficient use and reallocation of public resources is going to prove vital if the looming public spending scenario is not to result in poorer-quality public services that are below the standards of Spain’s peers. The spending review which the Spanish government has commissioned the AIReF to prepare in 2017 against the backdrop of the recommendations emanating from the European Commission is a step in the right direction. However, further steps are needed. Specifically, the central and regional governments need to tackle institutional reforms in order to foster the independent, thorough and continuous assessment of the social benefits of their investments and of their spending programmes in general.

Support for this paper provided by Fernanda Martínez and Alejandro Domínguez (GEN).

According to the Spanish Ministry of Finance and Civil Service (2017a), the output gap, which was still -3.3% in 2016, should narrow to -1.5% in 2017, balance in 2018 and return to positive territory in 2019 (+0.60%).

The Toledo Pact (Spanish: Pacto de Toledo) was an ambitious reform of the Spanish social security system approved by the Spanish parliament in April 1995, aimed at streamlining and guaranteeing the future of the Spanish Social Security system. Subsequently, a permanent parliamentary commission was created in order to monitor and modernise the pact and the system.

The package of tax measures, with an overall impact of 7.5 billion euros, included the elimination of tax breaks and deductions in respect of corporate income tax; an increase in the duties levied on tobacco and alcoholic beverages; a new tax on sugary drinks pending approval; phase one of a ‘green fiscal reform’ prioritising greenhouse emissions; changes in tax management (specifically, elimination of the scope for granting deferrals for output VAT, payment by instalments or suspended debts while an appeal is being processes); and, intensification of the battle against tax fraud.

References

AIReF (2017a),

Evaluación conjunta del objetivo de estabilidad presupuestaria de las Administraciones Públicas 2017 [Joint assessment of the government budget stability target for 2017], 25/4/2017. View at

www.airef.es — (2017b),

Seguimiento trimestral del objetivo de estabilidad del conjunto de Administraciones Públicas. Primer trimestre de 2017 [Quarterly monitoring of the stability target at the overall government level. 1Q17], 1/6/2017. View at

www.airef.es FUNCAS (2017), “Spanish economic forecast panel July 2017”,

SEFO, 6(4).

LAGO, S. (2014), “Fiscal Consolidation in Spain: Situation and Outlook”,

SEFO, 3(3): 45-52.

— (2017), “Spain’s Fiscal Consolidation: 2016 Performance and Outlook for 2017”

, SEFO, 6(2): 95-102.

LAGO, S., and J. MARTÍNEZ-VÁZQUEZ (2016), El gasto público en España en perspectiva comparada: ¿Gastamos lo suficiente? ¿Gastamos bien? [Public spending in Spain on a comparative basis. Do we spend enough? Do we spend well?],

Papeles de Economía Española, 147: 2-25.

SPANISH MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND CIVIL SERVICE (2017a),

Actualización del Programa de Estabilidad 2017-2020 [Updated Stability Plan for 2017-2020], 28/4/2017. View at

www.minhafp.gob.es — (2017b)

, Ejecución presupuestaria hasta el mes de mayo de 2017 [Budget outturn through May 2017], 27/6/2017. View at

www.minhafp.gob.es

Santiago Lago-Peñas. Professor of Applied Economics and Director of the Governance and Economics Research Network (GEN) Vigo University