Basel III reforms and implications for European and Spanish banks

The conclusion of Basel III reforms will, on the whole, increase capital requirements for European banks. Nevertheless, the reduction of regulatory uncertainty and the resulting increased resilience for the EU banking system should support a more constructive outlook for the sector over the medium to longer-term.

Abstract: On December 7th, 2017, the oversight body of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) announced the finalisation of the Basel III reforms, initiated in December 2010, which mainly affect three major classes of bank risk: credit, operational and Credit valuation adjustment (CVA). The changes are set to have an impact on European banks as they are expected to increase the Tier 1 minimum capital requirements by 12.9%.

Introduction

On December 7th, 2017, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s oversight body, the Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision (GHOS), announced the completion of the global reform of the banking regulation framework known as Basel III (BIII), which began in December 2010, when two documents key to this process were issued, one addressing capital requirements (BCBS, 2010a) and the other, liquidity (BCBS, 2010b) (note that the latter is not affected by the conclusion of the process).

Against that backdrop, this paper attempts to achieve two fundamental objectives:

- Outline the key characteristics of the changes to international banking regulations implied by the completion of BIII.

- Estimate the influence that conclusion of the process will have on the European banks as a whole, without focusing on any institution in particular.

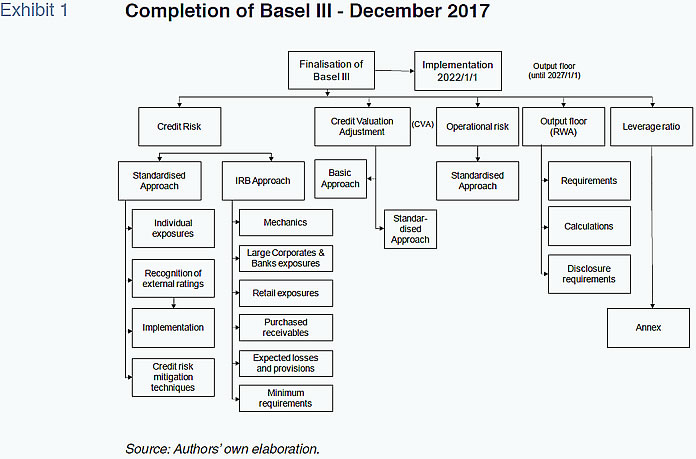

Both objectives are complex on account of, on the one hand, the scope and depth of the changes prompted by the completion of BIII, as depicted in Exhibit 1, provided in the next section of this paper, and the need for information that is not publicly disclosed by Spanish banks affected, on the other.

However, given that the length of this paper is limited, in both instances we rely on the documents published by the BCBS and by the European Banking Authority (EBA) for the second objective. Indeed:

- The BCBS has published a formal document regarding the finalisation of BIII (BCBS, 2017a: 162 pages) and a summary thereof (BCBS, 2017b: 20 pages).

- The BCBS has also published a quantitative impact assessment (BCBS, 2017c: 49 pages), based on a sample of 248 entities across 25 countries, almost all of which are members of the BCBS (23 of the 27 members), and the EBA has published a similar analysis (EBA, 2017: 28 pages), using a sample of 149 banks from 17 EU countries.

Note that credit risk tends to be the most significant area of change for the banks as a whole and this is certainly the case in Spain, as is evident in the Bank of Spain’s analysis (2017, on page 69), which states that credit risk is responsible for 87% of risk-weighted assets (RWA), followed by operational risk (9%) and position, and exchange and commodity risk (3%), sometimes termed market risk. The other risks account for around 1%. This means that we are well justified in focusing on credit risk, the area subject to the greatest change upon completion of BIII [1].

The changes in the treatment of credit risk would in all likelihood have been more significant had there been any substantial change in the risk weights assigned to sovereign exposures, the standardised approach to which, as the final report confirms, has been left unchanged with respect to the Basel II reforms of June 2006, having failed to secure a consensus as to how to change them.

Instead, the BCBS has issued a discussion paper (BCBS, 2017d: 45 pages) on the subject. That document, which will not be referred to again in this paper, sums up in a manner we view as very holistic and comprehensive the issues raised by these exposures, while also weighing up potential ideas, albeit without putting forward any specific proposals, pending responses from stakeholders which are due by March 9th, 2018.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, it is very likely that the treatment of sovereign exposures was used as a bargaining chip among the various parties when it came to defining the scope of the so-called output floor.

This paper does not take into consideration the fact that the final terms of BIII must be incorporated into EU regulations on capital requirements for credit institutions, essentially Directive 36/2013 (the Capital Requirements Directive IV or CRD IV) and Regulation 575/2013 (CRR), which do not always echo what is decided by the BCBS word for word but do tend to stay close to script on the important points. The capital requirements package is in the process of undergoing several modifications, not all of which are related with BCBS initiatives.

What’s new in Basel IIIExhibit 1 synthesises the contents of the final BIII report. It illustrates how three major sources of bank risk are affected:

- Credit risk

- Operational risk

- Credit valuation adjustment (CVA) risk

The BIII reforms were undertaken with one overriding objective in mind, namely reducing the excessive observed variability in the risk weights applied across the various entities, variability which undermines the validity of the regulatory approach and impedes comparability across entities. This objective is achieved in three ways:

- Fortifying the solidity and risk sensitivity of the standardised approach to credit and operational risk;

- Restricting the use of internal ratings-based models, whose use is not obligatory. In fact, a jurisdiction that only uses standardised approaches is BIII compliant.

- Rounding out the capital ratio with a leverage ratio, which is ultimately the unweighted capital ratio, and establishing a new RWA floor.

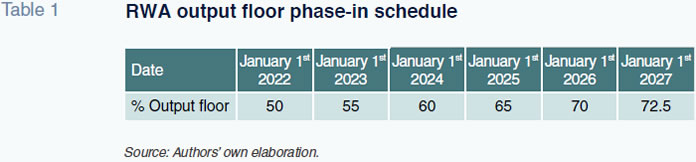

In the spirit of the philosophical approach taken by the BIII reforms since they were embarked on in December 2010, which calls for staggered implementation, the changes analysed in this paper are in general due to take effect on January 1st, 2022, i.e., in four years’ time, which would seem more than enough headroom for any banks needing to make adjustments. The RWA floor adds another five years to the transition arrangement, as it will be introduced on a staggered basis starting in 2022:

Credit risk

Standardised approach

As for individual exposures, the final document contemplates the following classes of exposures:

- Exposures to sovereigns, whose risk weights are unchanged since 2006 as already noted above

- Exposures to non-central government public sector entities (PSEs), also unchanged from the Basel II framework

- Exposures to multilateral development banks (MDBs)

- Exposures to banks

- Exposures to covered bonds

- Exposures to securities firms and other financial institutions

- Exposures to corporates

- Subordinated debt, equity and other capital instruments

- Retail exposures

- Real estate exposure (residential and commercial)

- Exposures with currency mismatch

- Off-balance sheet items

- Defaulted exposures

- Other assets

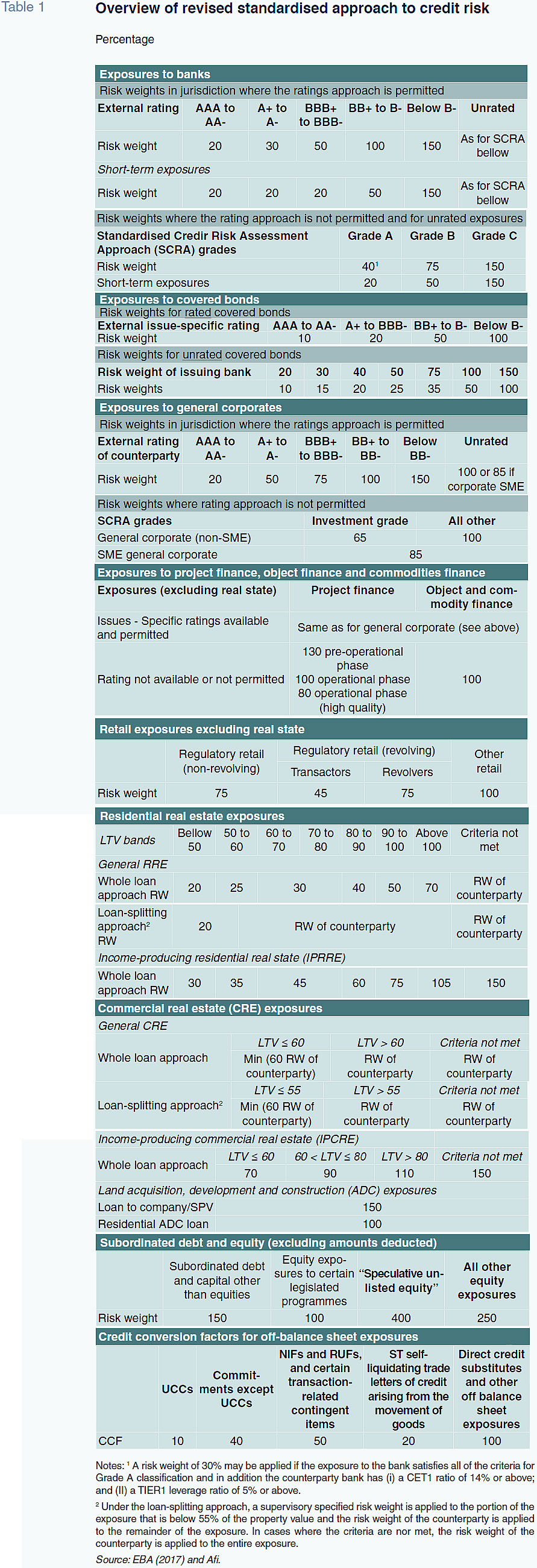

The most important changes to this approach are summarised in BCBS’s high-level summary (2017b), specifically Table 1 thereof, which we have reproduced as an appendix, as it is not our work. This table clearly depicts the increased risk weight sensitivity.

This phenomenon is perhaps most evident in secured residential real estate exposures, which are very important to Spanish banks as a whole, where the regulatory capital requirement has been revised from a flat weight of 35% to a range that goes from 20% and 70%, depending on the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio obtained by dividing the amount of the loan by the value of the property, subject to compliance with certain criteria, when repayment of the loan does not depend significantly on the cash flows generated by the property. That ratio will tend to fall as the loan is repaid, with the corresponding reduction in exposure for the lender bank.

Looking beyond individual exposures, another very significant change is the reduction in the mechanical use of external credit ratings (gleaned from rating agencies) which not all jurisdictions necessarily recognise. Where they are relied upon, the banks must carry out due diligence, appropriate to the size and complexity of the banks’ activities, to ensure that they have an adequate understanding, at origination and thereafter on a regular basis (at least annually), of the risk profile and characteristics of their counterparties so as to assess whether the risk weights applied are appropriate and prudent.

This requirement has important implications for the management of credit risk, such as the need to develop internal policies, systems and controls that may be subject to inspection by the supervisors as well as the unquestionable need to collect more information on banks’ counterparties on a regular basis.

Internal ratings-based (IRB) approaches

These ratings, where permitted, relate to the following classes of exposures, in some cases with sub-categories:

- Exposures to corporates

- Exposures to sovereigns

- Exposures to banks

- Retail exposures

- Equity exposure

In this instance, the above-mentioned objective (with even more reason insofar as we are talking about ratings obtained using methods that can be highly complex and, above all, scantly transparent on account of being internal) is to achieve two things, aside from other technical refinements:

- Elimination of the advanced IRB (A-IRB) method which allows banks to estimate all the relevant parameters for certain exposures, specifically for:

- Exposures to large and mid-sized corporates

- Banks and other financial institutions

- Exposures to equities (for which only the standardised approach will be permitted)

- Specification of input floors for certain key variables:

- Probability of default (PD)

- Loss given default (LGD)

- Exposure at default (EAD)

These changes, which we do not believe warrant describing in detail, made way for elimination of the 1.06 scaling factor currently applied to RWAs determined by the IRB approach to credit risk.

CVA risk framework

The adjustment for this risk, which falls somewhere between credit and market risk, applies to derivative instruments and securities financing transactions (SFTs) and constitutes a capital charge for potential mark-to-market losses as a result of the deterioration in the creditworthiness of a counterparty.

It is a complex risk which is why the option of measuring it using IRB models has been removed. Instead, it will be measured using either a standardised approach or a basic approach. Whereas the first requires supervisory approval, in contrast to the standardised approaches for other risks, the second is the default option available to banks.

As with the other risks whose treatment has been revised, the CVA risk framework has also been the subject of technical refinements we do not believe are necessary to itemise.

Operational risk

The approach taken to operational risk, which is the result of internal processes, inadequate or failing human resources or systems and external events, including legal risk but not strategic or reputational risk, is in line with the revisions already outlined, going perhaps even further in this instance.

The approach to this risk has been drastically streamlined, with a renovated risk-sensitive standardised approach replacing the existing three standardised approaches as well as the advanced measurement approaches (AMA) for calculating operational risk capital requirements. The new standardised approach can be summarised as follows:

BIC x ILM,

where:

BIC is the business indicator, gleaned from the financial statements, and is the sum of three components:

- The interest (net), rentals and dividends component

- The services component

- The financial component, which includes the banking business itself and the trading portfolio

ILM is the internal loss multiplier, which takes into account the bank’s average historical losses over the preceding 10 years.

Leverage

Leaving aside the technical adjustments made to how this ratio is calculated, which affect derivative instruments and off-balance sheet exposures, and the fact that a given jurisdiction can opt to exclude reserves at central banks from the ratio on a temporary basis under exceptional macroeconomic circumstances, the most eye-catching change is the buffer for global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), such as Banco Santander in Spain.

As with other buffers, this buffer must be met with Tier 1 capital and is set at 50% of a G-SIB’s risk-weighted higher-loss absorbency requirements. As a result, for Banco Santander, which is at the lowest level of G-SIBs, to be totally free to pay out dividends, it must report:

- A capital conservation buffer of:

4.5% + 2.5% + 1% = 8%

- And a leverage ratio of:

3% + 0.5% = 3.5%

Output floors

When the Basel II framework was introduced in June 2004, a floor equivalent to 80% of Basel I capital requirements was introduced; this floor inevitably lost its rationale when the Basel I requirements, which dated to July 1988, ceased to be used.

The Basel III reforms replace it with a floor based on the revised Basel III standardised approaches to:

- Credit risk

- Counterparty credit risk

- CVA risk

- Securitisation

- Market risk

- Operational risk

The revised floor places a limit on the regulatory capital benefits that a bank using internal models can derive relative to the standardised approaches. It has been set at 72.5% of RWA, albeit subject to the extended implementation timeline referred to earlier in this report.

Banks are required to report their RWAs calculated using standardised approaches, which will enable verification of compliance with the floor.

Estimating the impact on European banks

To assess the impact of the new Basel III framework on the European banks, we start from the full impact assessment report published by the EBA on December 20th, 2017. The EBA’s sample included 149 banks from 17 countries, divided into two groups. Group 1 banks are those with Tier 1 capital in excess of 3 billion euros and internationally active. All other banks are categorised as Group 2 banks. These criteria put 44 banks in Group 1 and 105 in Group 2. Of the 149 banks, just 88 provided sufficient data to perform the analysis (36 from Group 1 and 52 from Group 2).

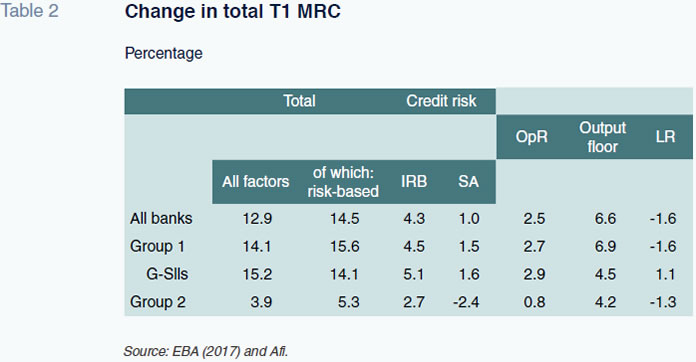

The impact, without factoring in the changes to the securitisation or CVA frameworks, shown in Table 2 below, can be summed up as follows:

- An estimated 14.5% increase in the minimum capital requirement as a result of the risk-based elements, which in turn is broken down into:

- a 4.3% increase for banks that use internal models (IRB); 1.0% for the banks that use standardised approaches; 2.5% in respect of operational risk; 6.6% on account of the introduction of a new output floor; partially offset (-1.6%) by the negative impact of the new leverage ratio.

- The Group 1 entities are more affected by the above changes (+14.1%) than their Group 2 counterparts (+3.9%), given that the former make greater use of internal models and the introduction of the RWA floor of 72.5% limits the extent to which banks can lower their capital requirements relative to the standardised approaches.

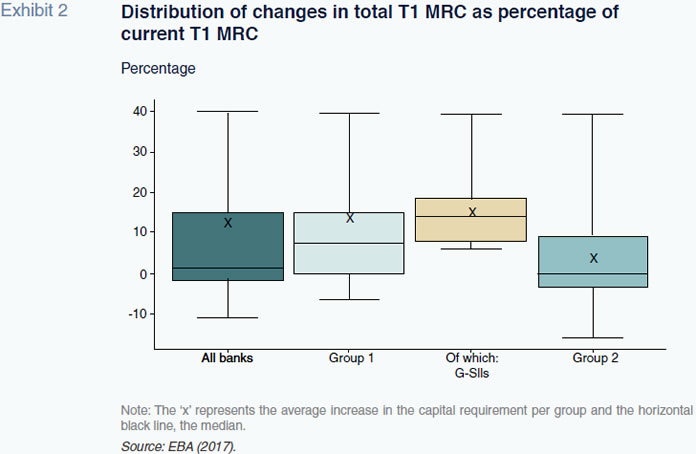

Exhibit 2 illustrates the dispersion among the entities analysed in the EBA’s assessment, evidencing the heterogeneity across Europe’s banks prior to finalisation of BIII. It shows that while some entities will see their Tier 1 minimum capital requirement increase by as much as 40%, others will see it fall by 12%.

This heterogeneity derives from the use of internal models at some banks and not others and evidences how the new reforms have tightened up the capital required of the entities that rely heavily on those models.

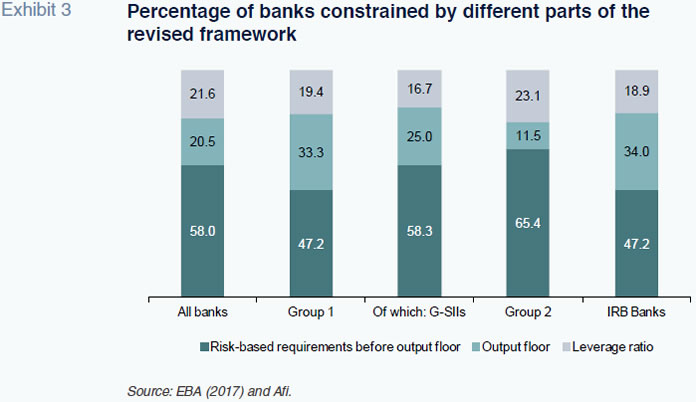

To wrap up our description of the estimated impact, refer to Exhibit 3, in which the EBA illustrates the percentages of banks affected more considerably by the three key areas of reform analysed: (i) risk-based requirements before the output floor; (ii) the output floor; and, (iii) the leverage ratio. The conclusions could not be clearer: 58.0% of the entities analysed will be affected by the revised risk-based requirements, whereas 42% will be constrained by the other two reforms (specifically, 20.5% by the introduction of the output floor and 21.6% by the leverage ratio).

However, the heterogeneity observed across entities above is once again apparent. If we analyse only the banks that use internal models, the percentage constrained by the introduction of the new floor rises to 34%, with the other percentages falling as a result.

This may well discourage the entities whose ratios are nearer the limits introduced by the BIII framework from using IRB approaches.

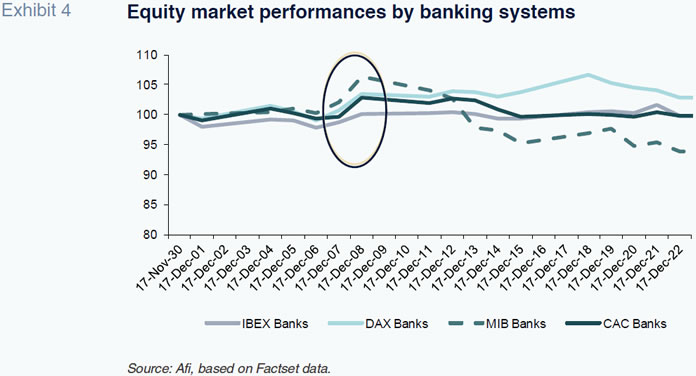

Stock market response to completion of Basel IIIAs stated previously, the regulatory reforms were prompted by excessive RWA variability among entities with similar business models and attempt to advance on defining RWAs in order to prevent that variability. Against this backdrop, completion of the Basel III framework was initially welcomed by the markets: banks saw their share prices rally in the wake of publication of the final report, as shown in Exhibit 4.

In the case of the listed Spanish banks, publication of the document meant making up the 3% lost between November 30th and December 7th (rebased: November 30th =100).

Following the initial bounce that followed publication of the report, the Italian banks’ share prices fell, evidencing other problems intrinsic to that banking system (high NPLs, political risk, etc.), while the other major banking systems (Germany, Spain and France) headed into the holiday period at levels very similar to those at which they had started the month.

As we have noted on previous occasions, regulatory uncertainty has been one of the factors shaping the banking systems’ equity market performance. Completion of the BIII reforms marks the reduction of one source of regulatory uncertainty, reinforcing capital in the banking sector.

ConclusionsWe believe that completion of the BIII reforms brings a series of noteworthy implications:

- They dissipates some of the uncertainty that may have been hanging over some of the banks’ share prices, as evidenced by the rally in the days following the announced endorsement of the new framework.

- They step up regulatory capital requirements for both the banks that use standardised approaches and those that use internal models, a change from earlier assessments that placed all of the spotlight on the banks using internal models.

- That being said, the new requirements are more onerous for banks using internal models than those using standardised approaches.

- Indirectly, looking to the medium term, an increased ability to withstand episodes of crisis should help to reduce wholesale and retail funding costs and bring down the cost of capital itself.

- The reforms increase the risk sensitivity of the standardised approaches, thereby introducing greater discrimination in RWA calculation as a function of the business model pursued.

- They may well discourage the use of internal models to calculate RWAs on the part of entities whose metrics are closer to the thresholds introduced by BIII.

- The new standardised approach to calculating RWAs implies a challenge in terms of the information needed to be able to discriminate between risks, while the new approach for estimating operational risk will mean having to create and keep records of historical losses on account of this risk factor.

- We do not believe that the new framework will imply the abandonment of internal models for managerial use to estimate economic capital or the risk-adjusted returns generated by the various business units.

Notes

106 pages of the BIII finalisation document are devoted to the two credit risk measurement approaches, the standardised approach and internal ratings-based methods, which is 65% of the total.

References

BANK OF SPAIN (2017), Financial Stability Report, November. Retrievable from https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/Seccioes/Publicaciones/ InformesBoletinesRevistas/InformesEstabilidadFinancera/ 17/IEF_ Noviembre2017.pdf

BASEL COMMITTEE ON BANKING SUPERVISION, BCBS (2010A), Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems, December. Note that all BCBS publications can be retrieved from the Bank for International Settlement’s website: https://www.bis.org/bcbs/ publications.htm).

— (2010b), Basel III: International framework for liquidity risk measurement, standards and monitoring, December.

— (2017a): Basel III: Finalising post-crisis reforms, December.

— (2017b): High-level summary of Basel III reforms, December.

— (2017c): Basel III Monitoring Report. Results of the cumulative quantitative impact study, December.

— (2017d): The regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures – discussion paper, December.

EUROPEAN BANK AUTHORITY, EBA (2017), Ad hoc cumulative impact assessment of the Basel reform package, December 20th. Retrievable from http://www.eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/1720738/ Ad+Hoc+Cumulative+Impact+Assessment+of+th e+Basel+reform+package.pdf

Fernando Rojas, Esteban Sánchez and Francisco José Valero. A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.

Appendix