The Spanish labour market: Cyclical behaviour and structural challenges

An examination of employment and labour market participation reveals the Spanish labour market is pro-cyclical in nature, in part, explaining the relatively high unemployment rate essentially prevailing over the past two decades. New reforms are needed in order to make employment less pro-cyclical and tackle persistent structural imbalances in terms of job quality, regional differences and skills attainment, especially in the context of the digitisation of the economy.

Abstract: Since the start of the financial crisis, the Spanish labour market has exhibited a highly volatile employment trend. After shedding nearly 4 million jobs during the recession, the unemployment rate has steadily declined, with 30% of eurozone job creation occurring in Spain over the last 4 years. Interestingly, the labour force participation rate in Spain increased during the recession, the opposite of what would be expected. More recently, it has stagnated, while still remaining higher than in many other European countries, such as Belgium, France and Italy. On the other hand, the analysis of recent trends does not permit a clear-cut determination as to whether structural unemployment has increased as a result of the crisis: recent declines in long-term unemployment point to an optimistic picture; but prevailing education gaps, and regional differences in employment suggest a less favourable assessment, especially in view of the impacts of an increasingly digitised economy. Despite initial reform efforts already undertaken, the high correlation between the level of employment volatility and the rate of unemployment calls for policymakers to design initiatives that will address persistent imbalances in the Spanish labour market.

[1]

Introduction

The Spanish labour market has been one of the most dynamic in Europe since the global economy began to recover from the Great Recession. Between 2014 and the third quarter of 2018, it generated over two million jobs (net), which is just shy of 30% of all jobs created in the eurozone during that period. As a result, the unemployment rate has dropped by over 10 percentage points. This is a remarkable performance, though it has yet to make up for all of the ground lost during the crisis. Indeed, the scars inflicted on Spain’s economy by the bursting of the real estate bubble, and later by the sovereign debt crisis, have not fully healed.

This paper attempts to describe the main characteristics of the labour market emerging in the current business cycle and identify to what extent the prevailing trends mark a break from prior patterns. The paper also analyses some of the key challenges facing the labour market in the years to come and briefly discusses possible employment prospects.

The labour market in the current economic cycle

One of the stand-out characteristics of the Spanish labour market is its exceptionally pro-cyclical performance in terms of jobs, labour market participation and unemployment.

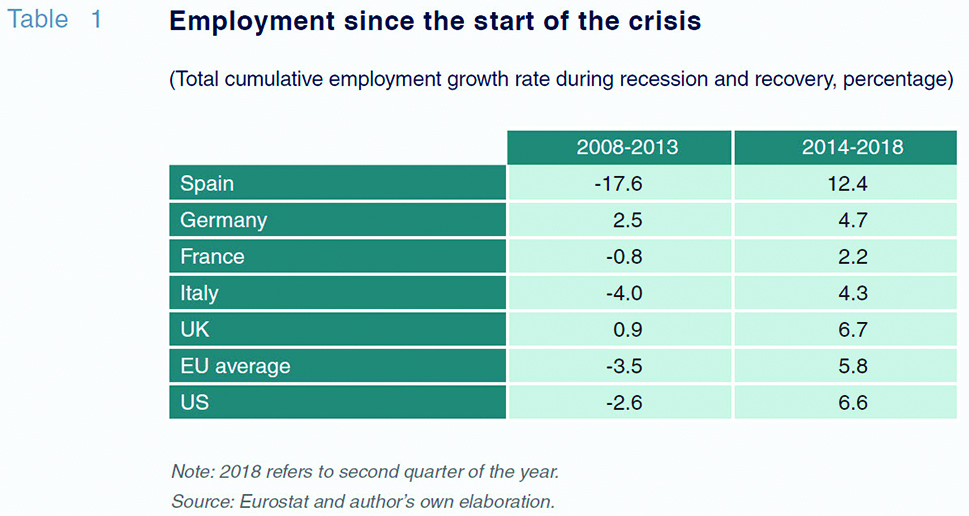

Employment, which fell sharply during the recession, has proven particularly buoyant during the recovery. Between the first quarter of 2014 and the second quarter of this year, Spain created more jobs than any other European country. Employment increased by over 12% during that period, which is twice the European average (Table 1). From a quantitative perspective, the gender employment gap has narrowed, though women remain at a disadvantage in other ways, including pay and working conditions. Importantly, all age brackets have benefitted from the growth in employment.

Nevertheless, employment has yet to recover to pre-crisis levels. The number of people employed in Spain peaked during the third quarter of 2007 at 20.8 million, after which it dramatically declined to a low of 17 million in the first quarter of 2014. Since then, employment has been trending higher, reaching 19.5 million in the third quarter of 2018 (the most recent figure available). This implies another 1.3 million jobs still need to be created in order to return to the pre-crisis employment level.

The gap is even wider if we consider the fact that despite emigration and the decline in immigration, the working-age population has continued to increase. As a result, the employment rate (i.e., the number of people in work as a percentage of the working-age population) stands at 62.3%, compared to 65.9% in the third quarter of 2007. To get back to that previous level, the Spanish economy would have to generate an additional 2.2 million jobs.

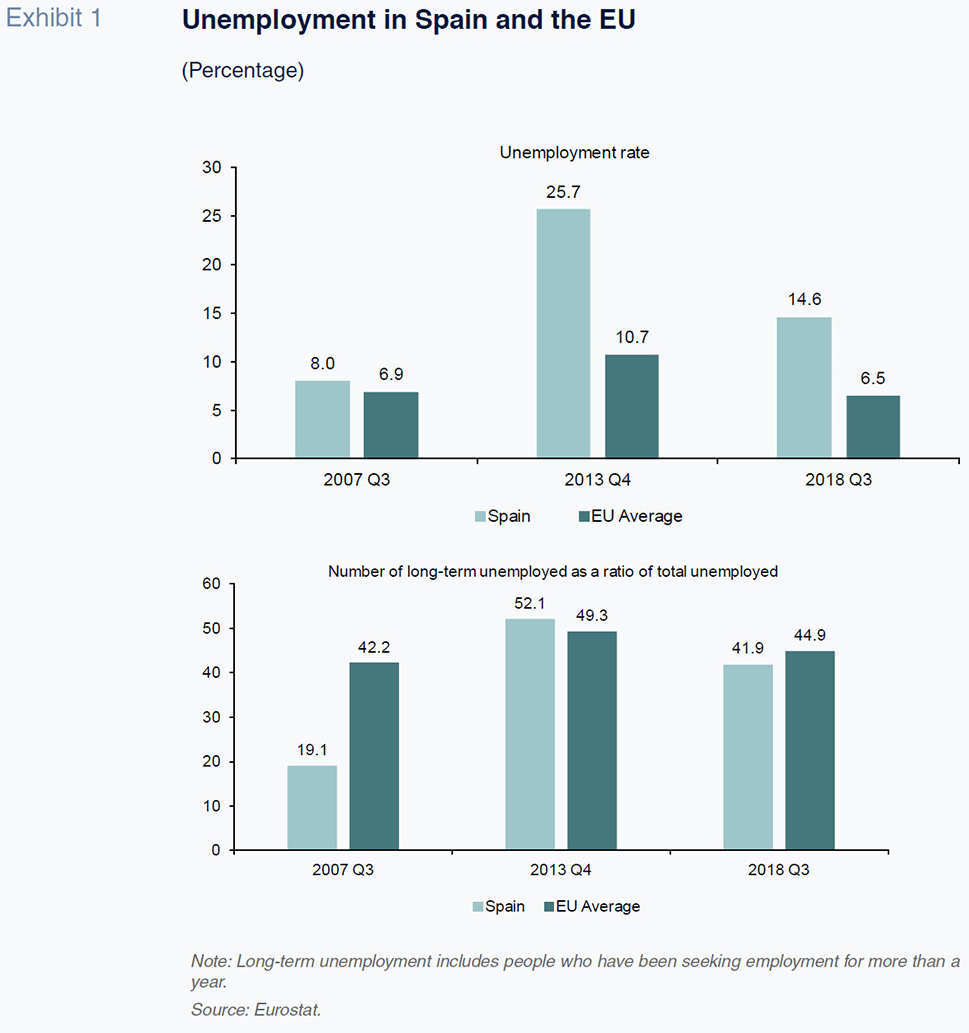

As for unemployment, its responsiveness to the business cycle has been even more pronounced (Exhibit 1). During the recession, the number of job-seekers increased by over 4.3 million, which is higher than the number of jobs lost, as well as being a European record. In contrast, the subsequent growth has been accompanied by a contraction in unemployment to the tune of around 3 million. No other developed country has achieved a decrease of that magnitude.

Even so, the unemployment rate is still significantly higher than it was before the crisis. The reason is that during the crisis, unemployment increased at an average pace of over three percentage points per annum, which is faster than the improvement sustained during the recovery. Consequently, Spain’s unemployment rate is still one of the highest in the developed world. Within Europe, it is second only to Greece.

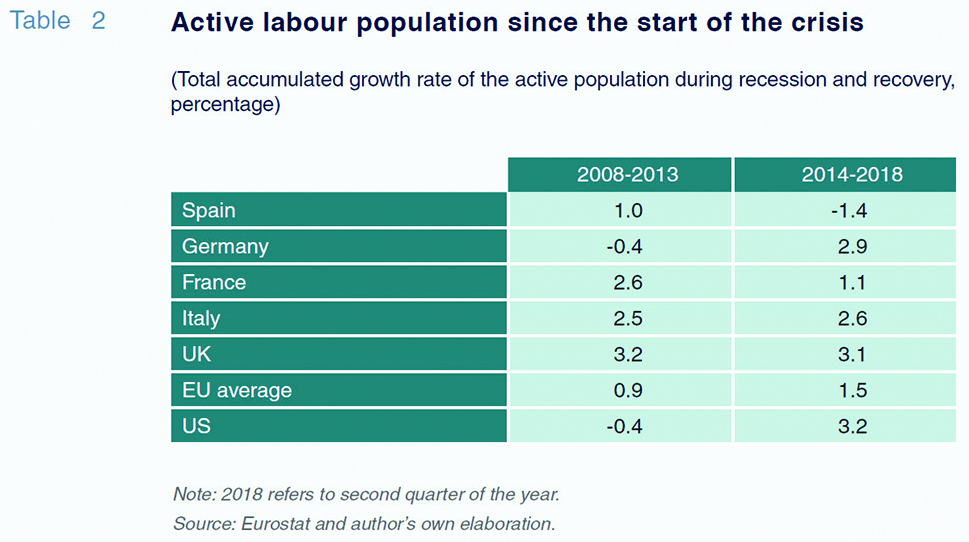

The exceptional pro-cyclical response in unemployment reflects a curious trend in the participation rate (

i.e., the percentage of the working-age population that engages actively in the labour market, either by working or looking for a job). In theory, the number of labour force participants tends to drop during recessionary periods, as long-term job seekers become discouraged and certain groups at risk of exclusion (young people without higher education, single parents with small children and people living in depressed areas) encounter difficulties in finding work (Duval, Eris and Fuceri, 2010). Conversely, growth is usually accompanied by higher participation levels. In short, the participation rate is supposed to be pro-cyclical, as is the case in countries such as the US (Table 2).

However, in Spain the opposite has been the case. The labour force participation rate continued to climb during the recession, which is largely attributable to the trend-increase in female labour participation. Another reason relates to the structural change among older workers (over the age of 55), who are opting to prolong their working lives. The level of participation of older workers has increased in recent years, which is important in the context of population ageing. This trend contrasts with the early retirement or exit from the labour force observed in several European countries, such as Austria and Belgium, as well as in prior recessions in Spain.

It is harder, however, to account for the stagnation in the participation rate during the current period of growth. One explanation is the tendency for young people to extend their study periods. Whereas nearly half of the group aged between 15 and 24 participated in the labour force before the crisis, the latest numbers suggest that just one-third of this age bracket currently does. This is the lowest rate among European countries. Only Italy has suffered a significant decrease in the rate of participation of its young people since the start of the crisis. That said, this is not a new trend.

Another contributing factor is the drop in the participation rate of prime working-age men. This is a indeed a new phenomenon in Spain, and also one that has been observed in other regions like the US and Northern Europe (Winship, 2017).

Regardless, the current labour force participation rate in Spain compares favourably with those in neighbouring countries. It is at the high end of the ranking in Europe and significantly above the participation rates in Belgium, France and Italy. Only Germany and the Scandinavian countries present significantly higher participation rates.

Putting together all these trends, the deficit of jobs among young people appears to be a key factor behind the overall employment gap. Indeed, quantitatively, the employment gap between Spain and the European average is largely attributable to results on the youth employment front. The reduction in the youth participation rate may reflect growth in the time spent in the education system, which would be a good thing from the standpoint of the country’s potential output. As we will see later, however, this is not the only explanation.

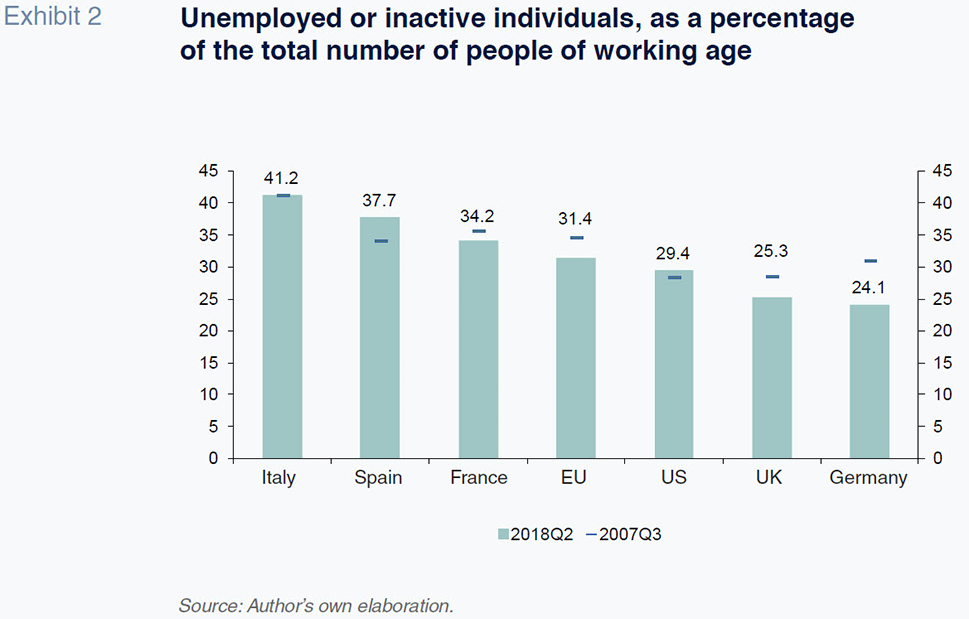

Key structural challengesBeyond the economic cycle, Spain’s persistently high level of unemployment is a cause of concern. Combining unemployment and labour force inactivity (Exhibit 2), we see that the employment deficit is indeed high by international comparison. There is a risk that prevailing imbalances will self-perpetuate, so that economic growth alone will not be sufficient to remedy them.

Risk of perpetually high unemployment

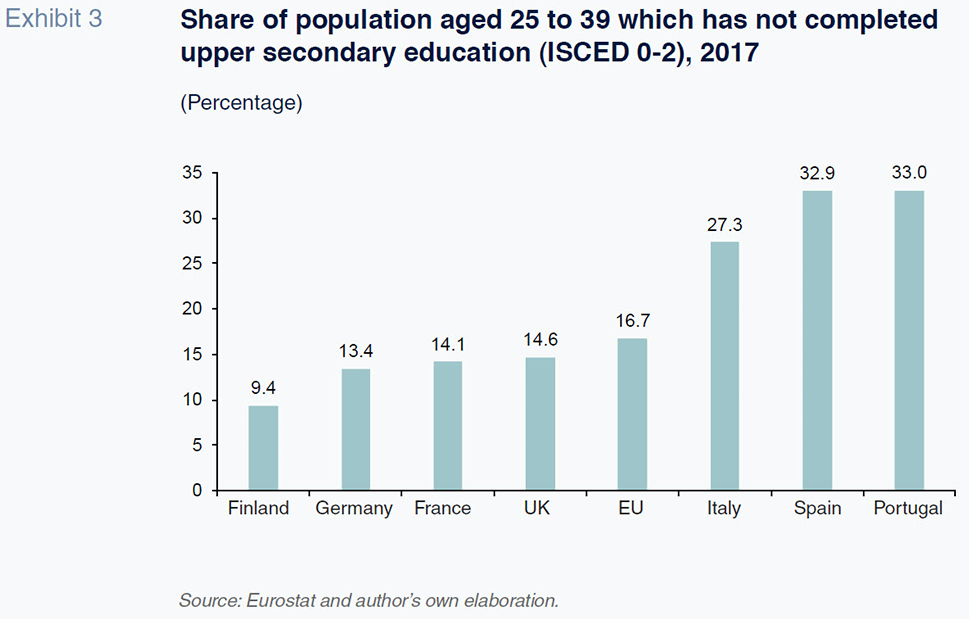

Analysis of recent trends points to mixed findings regarding whether structural unemployment has increased as a result of the crisis. Some characteristics of unemployment in Spain suggest this may indeed be the case. Firstly, the level of education of many job-seekers is relatively low. Indeed, although education levels have improved substantially, the results are uneven. The average training level attained by the Spanish working-age population is still well below the European average (Exhibit 3). Nearly 3 out of every 10 people of working age have only achieved a level of ‘lower secondary education’ or less (ISCED levels 0 to 2), which is virtually the European record, only ahead of Portugal. Moreover, this situation is barely improving as the percentage of early leavers from education is still 36% among Spaniards aged between 25 and 39. These educational shortcomings have ramifications for the job market. Additionally, 53% of job-seekers have credentials below secondary education levels, the highest percentage in Europe after Malta. Regrettably, adult vocational training fails to offset the deficits in early education, with vocational training only accentuating these initial inequalities.

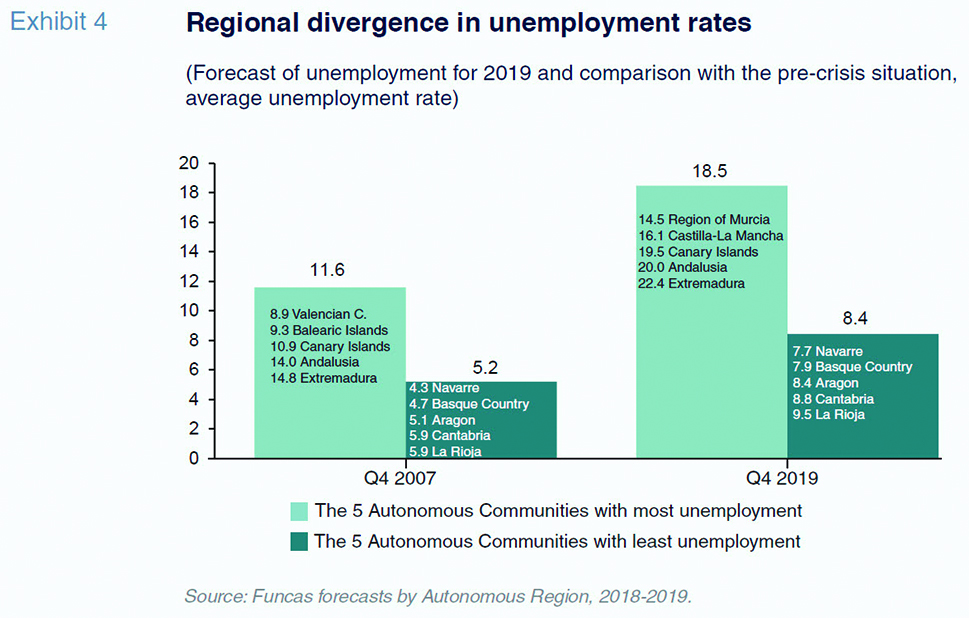

Secondly, regional imbalances have become more pronounced. The rate of unemployment in the hardest-hit regions stands at 18.5%, which is approximately 10 percentage points higher than the best-performing regions. However, this difference stood at just six percentage points prior to the real estate bubble bursting (Exhibit 4).

Other unique trends have emerged in the Spanish labour market (Torres, 2018 and Funcas, 2018). To start with, despite the vigorous growth sustained during the current phase of recovery, most of Spain’s autonomous regions continue to suffer from a serious shortfall of jobs. This is most evident in the south of the country and the Canary Islands compared to Madrid or the northeast of the country. Those regions that fail to remedy this job deficit run the risk of secular stagnation, as seen in Italy’s Mezzogiorno.

Meanwhile, other parts of Spain are beginning to experience a scarcity of workers. The unemployment rates in Navarre, the Basque region, Aragon, Cantabria, La Rioja and the Balearic Islands are close to their pre-crisis levels, with unemployment expected to fall below 10% by the end of 2019. Given the prospect of a shortfall of workers, companies will be left with no choice but to increase their productivity. That will open the door to wage increases and favour mobility on the part of job-seekers from other regions. Otherwise, growth in those regions will hit a ceiling.

The rural and inland expanses that are facing depopulation are a separate matter. Although employment in these regions is barely rising, labour force shrinkage is translating into a considerable drop in unemployment. Rural provinces such as Lugo and Soria present some of the lowest rates of unemployment. In these regions, the challenge is to maintain their population levels and attract new, young workers.

As a result, the gap between regions in terms of employment and population could become a key source of imbalance in the Spanish job market and undermine efforts made to combat unemployment.

Though the growing skill gaps and regional differences point in the direction of higher structural unemployment, other indicators paint a more optimistic picture. This is notably the case with recent trends in long-term unemployment –which warrants close attention on account of its social, human and economic impacts (Junankar, 2011). The empirical evidence suggests that people who have been looking for work for more than one year (the long-term unemployed) tend to experience mental health issues and a loss of self-esteem as a result of their job situation. The studies also show that these job-seekers face numerous obstacles in finding work. As a result, they tend to remain unemployed or are forced out of the job market due to discouragement or loss of job skills. In Germany, for example, long-term employment is relatively unresponsive to economic improvement. That country’s long-term unemployment rate has barely come down in recent years. Long-term unemployment is even more inert in France and Italy.

However, the Spanish labour market appears less vulnerable to the risk of self-perpetuating long-term unemployment. For example, half of the decline in total unemployment recorded during the recovery is due to a decline in long-term unemployment. The flow figures also show that the probability of finding work again is relatively high by international comparison. This result cannot be attributed to active public policies, whose effectiveness presents room for improvement. Among the possible factors, the following stand out: hiring dynamism; the existence of sectors, such as the hospitality sector which are capable of taking on people out of work, albeit somewhat seasonally; society’s resilience to the unemployment phenomenon, particularly in comparison with other countries, such as the Netherlands where prolonged joblessness is considered a serious stigma and disability, resulting in entitlement benefits.

Regardless, the responsiveness of long-term unemployment to the cycle may indicate that structural unemployment is not as high as some estimates have suggested (see for example, Romero and Fuentes, 2017). The moderate evolution of wages, suggestive of significant labour market slack, points in the same direction.

Temporary work

As mentioned above, the extreme pro-cyclical nature of employment in Spain is a significant vulnerability for the country’s economy. One of its structural causes is the temporary nature of many of the jobs created. Short-term contracts, of which many last less than a week, temp work, dependent self-employment and job switching are phenomena that are deeply entrenched in the Spanish job market.

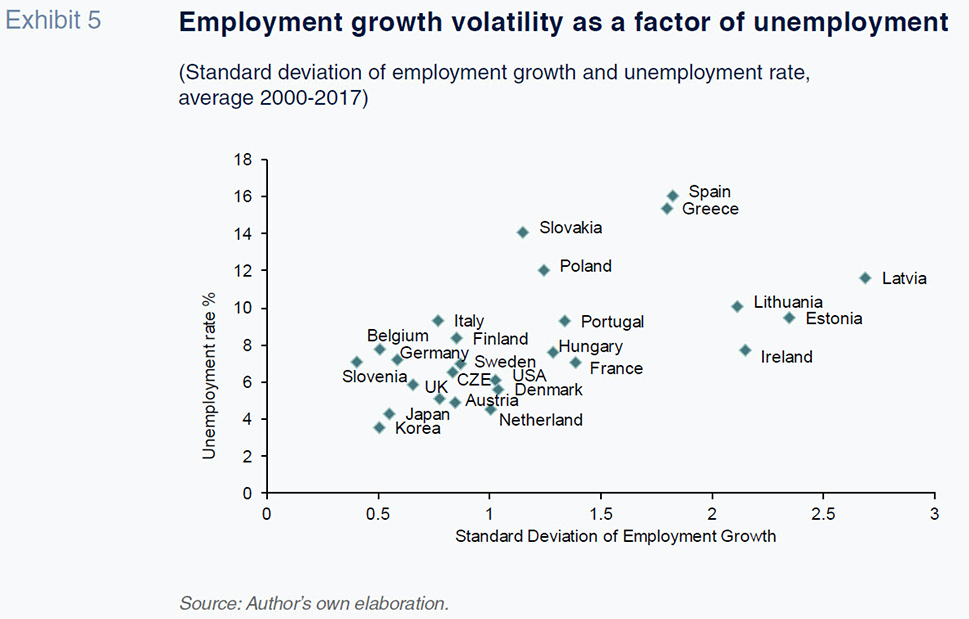

Importantly, temporary arrangements translate into higher volatility in job creation. And volatility tends to lead to higher unemployment: the net balance between periods of growth and contraction indeed appears to be negative. This is the logical outcome as the adjustments made via headcount reductions (rather than work redistribution or wage flexibility) tend to be costly in terms of long-term unemployment. The fact is that there is an empirical cross-country correlation between job volatility and the unemployment rate (Exhibit 5).

Although the incidence of these temporary arrangements has fallen slightly since the start of the year, we cannot say there has been a break with respect to this long-term trend. Young people are the main victims of these precarious arrangements. As already noted, the young were the age group most affected by the crisis in quantitative terms, despite the fact that the percentage of young people neither in employment nor in education (NEETs) has fallen substantially during the last five years, converging towards the European average. The young, however, continue to face two key challenges. Firstly, the percentage of early leavers from education is among the highest in Europe. The main reason for this is the draw of finding paid work, albeit relatively unskilled. Secondly, the jobs they do find when they enter the labour force tend to be precarious.

Low productivity and low wages

All of these imbalances are contributing factors to the scant growth in Spain’s labour productivity. Job volatility leads to a loss of human capital and business initiatives that would boost productivity. The shortcomings in the educational system drain human resources as well as curtail economic efficiency and deepen social inequalities. Finally, the persistence of high unemployment erodes the scope for tax collection, undermining the resources available for productivity-enhancing investment.

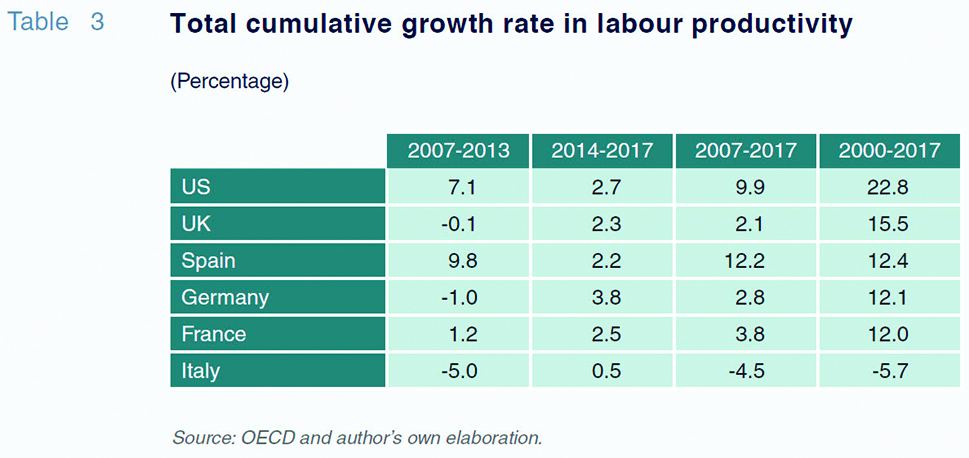

Labour productivity has not grown enough to drive convergence with Europe’s more prosperous economies (Table 3). Moreover, by definition, the trend in productivity limits wage growth. In the context of high unemployment, growth in remuneration has lagged even the weak growth in productivity (Table 4).

The relative stagnation of productivity is particularly worrying in the context of rapid technological change, which requires, inter alia, secure labour mobility paths, strong generic skills so as to adapt to change, new skills that respond to emerging requirements and a responsive enterprise environment which is capable of seizing upcoming opportunities. As noted, however, these are areas where the Spanish labour market exhibits important weaknesses.

To understand the consequences of present barriers to productivity growth in Spain, it is crucial to highlight the deep transformations which are associated with ongoing technological changes. First, the digital economy implies significant change to production patters, towards increasing fragmentation (ILO, 2015). It will impact the universe of enterprises, which can fragment the production process through value chains. This is the so-called outsourcing phenomenon, where tasks previously performed in the same enterprise can be divided and distributed among different production units. Outsourcing also leads to interconnected production organisation methods so that countries do not necessarily compete with each other but rather find themselves in an environment of mutual relations. Another dimension of the outsourcing process is the tendency to participate directly in the productive process via platforms. It is no longer necessary to work for a firm under a traditional arrangement in order to provide services or goods to consumers. What counts in the digital economy is joining an economic exchange platform. In reality, a company’s productivity no longer depends on the size of its production unit or stock of capital but rather the density of its network connections.

The process, as measured by the incidence of global value chains, is on the rise, but is not recent (World Bank, 2017). The trend first emerged around 20 years ago, coinciding with the proliferation of information and communication technology. What is new, however, is that production fragmentation has spread and deepened to the point of challenging the traditional production model, which was consistent with stable long-term employment relationships. Which is to say that the worker can now find himself the smallest link in a value chain, all the more so in countries like Spain with widespread temporary employment arrangements.

Second, artificial intelligence represents a far greater shift than the digital economy –one for which Spain is not very well placed for the time being. It is likely to initiate an evolution towards an interconnected model populated by smaller productive units and framed by an environment of smooth-flowing economic relations. This may imply a disruptive leap, calling into question economic growth as we know it, i.e., a process of capital accumulation that requires a significant human effort in terms of savings, investment and work.

For one thing, many of the job-intensive sectors where Spain has a comparative advantage may replace people by machines (large parts of industry, services that do not require face-to-face interactions, such as logistics, etc.). Algorithmic processes are becoming increasingly powerful and may surpass human intelligence in countless automatable tasks (i.e., those entailing a degree of routine and repetition). Industrial robots, self-driving cars, voice and image recognition software and the use of sensors in commerce are just a few everyday examples of how artificial intelligence is becoming increasingly present in our lives.

As artificial intelligence advances, machines and algorithms will acquire the ability to learn, thereby taking on more sophisticated tasks. Machines are learning how to react to external events so as to improve their performance with a minimum of human intervention. In the phase of “advanced learning”, the accumulation of capital will be largely endogenous. Artificial intelligence thus has the potential to take over many non-automatable tasks. Ultimately, artificial intelligence could replace much of the existing tasks, although not others.

[2] Depending on the policy response (in terms of skills’ development, mobility, investment in innovation, and competition policy), there should be enough jobs for all. Otherwise, we could reach a situation of excess labour supply. This is also why it is so important to lift all the barriers that presently hinder productivity in Spain.

The main activities that will remain in the productive sphere are those that by their very nature require a human presence. In theory, they include the sectors that issue collective standards across all areas of society (politics, medicine, law, privacy protection,

etc.). It is also probable that care work and all manner of activities based on interpersonal relationships will create many jobs. Human-led innovation, in both fundamental and applied research, will also increase in importance. It is therefore essential for Spain to facilitate business creation and innovation in these sectors which hold the strongest job potential. Productivity is not just a matter of improving efficiency in existing industries and jobs. It also –and increasingly— necessitates an ability to move investment and jobs into new areas of activity which benefit the most from change.

[3]

Prospects

Despite numerous legislative reforms, some of the main traits of the Spanish labour market have proven surprisingly stubborn over the last few decades. Employment tends to respond pro-cyclically, such that unemployment comes down quickly during times of growth and vice versa during episodes of recession. Considering a full cycle, the average rate of unemployment is high and labour productivity gains are scant. Meanwhile, the incidence of temporary work arrangements is among the highest in Europe, which translates into inequalities and weak wage growth at the aggregate level. Importantly, this paper detects a cross-country correlation between the pro-cyclicality of the labour market (as measured by the degree of employment volatility) and the rate of unemployment.

One of the more encouraging developments is the increase in the female participation rate, which is currently among the highest in Europe, and in older worker attachment. Another positive trend is the responsiveness of long-term employment to economic growth. In other countries, long-term unemployment is more inert, implying the risk of labour force exclusion (the hysteresis phenomenon).

However, the situation is changing rapidly as a result of the technological revolution underway, which makes it more urgent to initiate a fresh reform agenda to cement the achievements made and correct the remaining structural imbalances. The shortcomings in terms of education and training, the quality of the jobs on offer, mobility and the emerging regional gaps are some of the key areas of unfinished business.

In the absence of inclusive reforms, the Spanish labour market will continue to enjoy impressive results in the short run, i.e. as long as the expansionary phase continues, which is until 2020 according to most analysts. However, a reversal of the cycle would, once again, provoke disproportionate job losses, thus undoing all the gains laboriously won over the past few years. On top of these cyclical fluctuations, a status quo scenario would considerably reduce the benefits, in terms of both job quality and real incomes, which can be grasped from the technological revolution which is underway.

A policy action scenario, while not altering the positive short-term prospects, would help make the labour market more resilient to shocks while also paving the way to higher productivity and adaptive capacity to new technology. There is still significant room to move along that path, but the window of opportunity is getting smaller.

Notes

The author would like to thank Romain Charalambos for his valuable research assistance.

There could be a relative abundance in terms of the production of goods and services, helping to resolve the issue of scarcity, the economy’s biggest problem. Only natural resources can limit the expansion of automated production.

In the sectors that comprise the non-automated economy, artificial intelligence will be used to complement human intervention (World Economic Forum, 2018). However, some researchers believe that artificial intelligence may also breach these barriers. They maintain, for example, that robots will have the ability to formulate collective standards (so-called collective artificial intelligence). This entails complex ethical conundrums.

References

DUVAL, R.; ERIS, M., and D. FURCERI (2010), “Labour Force Participation Hysteresis in Industrial Countries: Evidence and Causes,”

https://www.oecd.org/eco/growth/46578691.pdfFUNCAS (2018), “Regional economic forecasts. 2018-2019,” Funcas, retrieved from

https://www.funcas.es/Indicadores/Indicadores_img.aspx?Id=4&file=0ILO (2015). “The changing nature of jobs,” retrieved from

https://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/2015-changing-nature-of-jobs/WCMS_368640/lang--en/index.htmJUNANKAR, P. N. RAJA (2011), The global economic crisis: Long-term unemployment in the OECD,

IZA Discussion Papers, No. 6057, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-201111072659ROMERO, M., and D. FUENTES (2017), “Spain´s structural unemployment rate: Estimates, consequences and recommendations”,

Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook (SEFO), March.

TORRES, R. (2018), “Paradojas territoriales del Mercado laboral español” [Spanish labour market: regional paradoxes],

El País, November 11th, 2018, retrieved from

https://elpais.com/economia/2018/11/09/actualidad/1541768094_950143.htmlWINSHIP, S. (2017), “What’s Behind Declining Male Labor Force Participation?,”

Federal Fiscal Policy Research Paper, retrieved from

https://www.mercatus.org/publications/declining-male-labor-force-participation-jobsWORLD BANK (2017), “The Global Value Chain Development Report,”

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/tcgp-17-01-china-gvcs-complete-for-web-0707.pdfWORD ECONOMIC FORUM (2018), “The Future of Jobs Report 2018,” Center for New Economy and Society,

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2018.pdf

Raymond Torres. Director for Macroeconomic and International Analysis, Funcas