The Spanish housing market post COVID-19

While COVID-19 did lead to an initial correction in Spain’s housing market, costs of home purchases have continued to rise, albeit with some differences across regions and type of housing. This has furthered a debate around housing affordability, including some misguided calls for rent controls.

Abstract: Surprisingly, COVID-19’s effect on the Spanish real estate market has been limited. The pandemic occurred during the “mature” housing cycle phase in terms of prices and transaction volumes. While GDP contracted by 17.8% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2020, the contractions in construction and property services amounted to 22.8% and 6.3%, respectively. Between June and September, both activities have recovered, registering growth of 24.8% and 6.4%, respectively. COVID-19 did, however, change the nature of the housing market, with rising demand for larger homes due to home working and declining demand for holiday homes thanks to mobility restrictions. Importantly, significant disparity in house prices exists across Spain’s regions. As well, the pandemic had a greater adverse impact on prices of new builds compared to existing homes. That said, COVID-19 had a more uniformly adverse effect on rental prices. In general, the pandemic has shone a spotlight on housing affordability issues, which Spain had been wrestling with since before the onset of COVIID-19, with numerous initiatives introduced to protect tenants during the crisis. While rental controls have been fl this would only lead to reduced supply and, ultimately, price growth, further hurting affordability.

Introduction

The financial crisis left a number of economic imbalances with a considerable social impact. The property market spent two decades working through the ensuing problems, in their various manifestations. Firstly, there was the imbalance created by the inordinate growth in construction and in prices, and, subsequently, the loan non-performance sustained when the property bubble burst. The social impact was similarly imbalanced: evictions increased and, despite the price correction, housing, whether for purchase or rent, remained out of reach for large swaths of the population.

The effect of COVID-19 on the property market originates from the closure of businesses, loss of jobs and restrictions on mobility. In theory, those are temporal issues. However, there are concerns that they could lead to a legacy of more permanent damage. Although the response to this crisis in the form of support mechanisms has been swifter than in the financial crisis, there remain many unanswered questions. Despite the progress being made on the vaccination front, the economic and social effects of the pandemic remain significant and are being felt in the real estate market. As a result, the Spanish government has extended some of the housing-related social relief measures until at least August, as outlined in this paper.

According to the Bank of Spain, the housing market was particularly affected in 2020 because of its position in the housing business cycle. The pandemic occurred during the “mature” phase in terms of prices and transaction volumes (Alves and San Juan, 2021). While GDP contracted by 17.8% year- on-year in the second quarter of 2020, the contractions in construction and property services amounted to 22.8% and 6.3%, respectively. Between June and September, both activities recovered, registering growth of 24.8% and 6.4%, respectively. However, the new restrictions introduced in the wake of the fresh outbreaks in the autumn and winter of 2020 once again took a toll, albeit a more moderate one than during the initial lockdown. In the first quarter of 2021, the construction sector contracted by 4.2% and property services, by 0.5%. The Bank of Spain also noted that the pandemic has triggered changes in the types of housing in demand, shaped by the circumstances created by the lockdown and home-working phenomenon. However, as shown in this paper, the price correction has been considerably less intense than during the financial crisis. What has not changed, however, is the disparity in price trends from one region to another. On the credit side, growth has been, in general, lukewarm, even though monetary policy continues to foster lax lending conditions. As well, we are beginning to see some signs of tighter lending conditions.

Situation and outlook

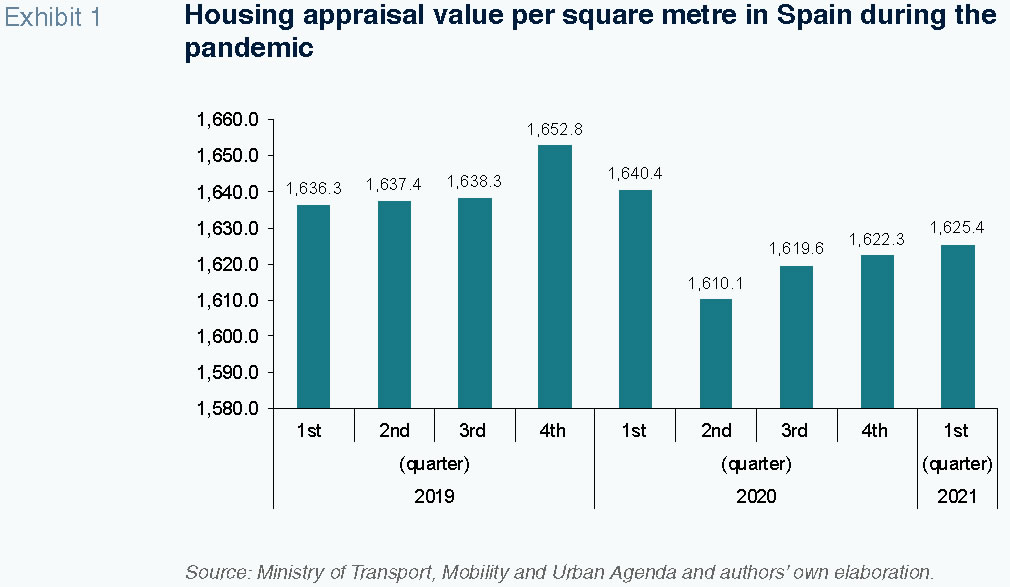

Spain lacks a uniform and detailed body of statistics for house prices and other indicators. [1] As a result, it is necessary to rely on a range of diff public and private sources to monitor unfolding trends. One key source for prices is the appraisal values published by the Ministry of Transport, Mobility and Urban Agenda. Exhibit 1 illustrates the trend in those values before and after the pandemic. Although the variations are not very significant, the exhibit shows how the negative impact was concentrated in the fi and, above all, second quarters of 2020. The average appraisal value of unsubsidised housing decreased from 1,652.8 euros/m2 in the last quarter of 2019 to 1,640.4 in the first quarter of 2020 and 1,610.1 in the second quarter. Since the third quarter of last year, appraisals have been recovering gradually.

Nevertheless, significant price disparity persists from one region to another. During the first quarter of 2021, when the appraisal value averaged 1,625.4 euros per square metre, the figure was 2,598.6 euros in Madrid, compared to just 833.5 euros in Extremadura. Regional house price disparity is more pronounced than that observed in income and wages and therefore signals differences in housing affordability that have been growing for some time.

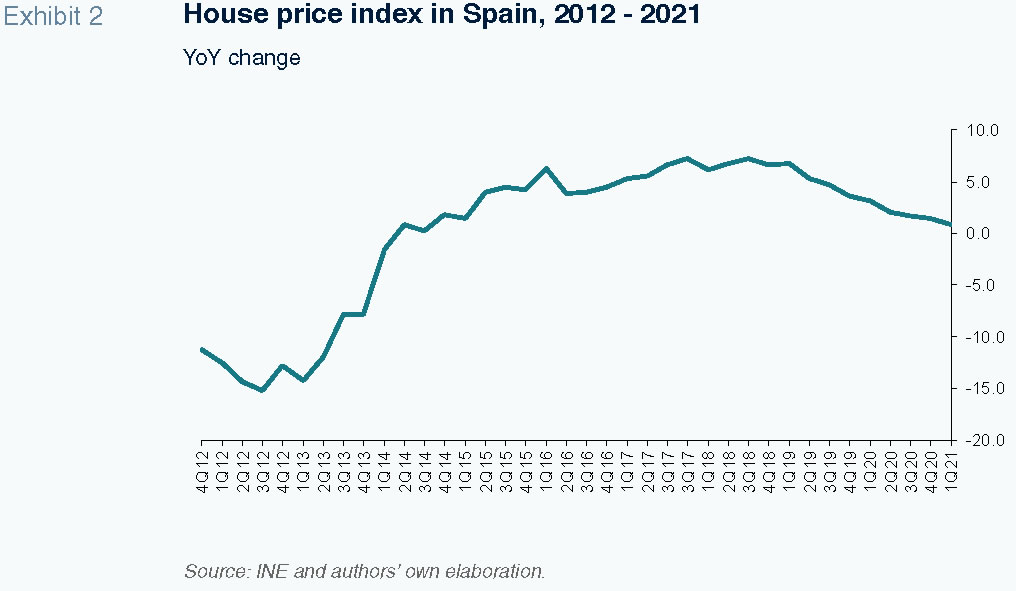

Another source is the house price index compiled by the National Statistics Office, INE. The INE builds its indicator from registry data, making adjustments for the quality of the properties (hedonic modelling). Although there tends to be discrepancy between actual sales values and those reported for property registry purposes, this index does provide a snapshot of the trend in prices over time. Exhibit 2 shows the year-on-year movement in the index. In keeping with the thesis that the property market was reaching a level of maturity or even exhibiting some softness toward the end of 2019, the exhibit shows that growth began to dip under 5% in the final quarters of 2019, with that slowdown continuing and accelerating since the pandemic, easing to 0.9% in the first quarter of 2021.

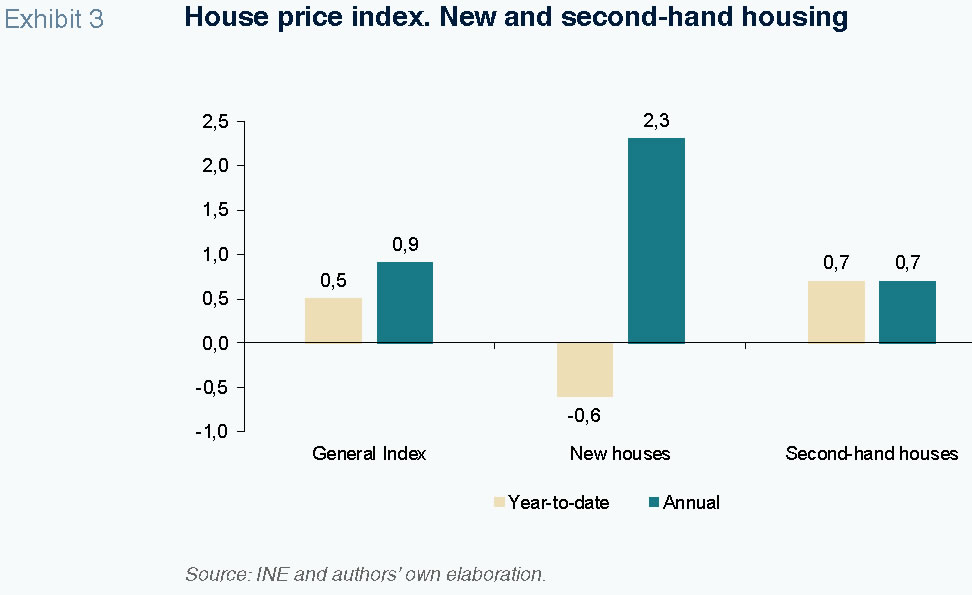

To zoom in on where the price correction has taken place, Exhibit 3 distinguishes between new and second-hand housing. That analysis shows it is the new housing market that sustained a price correction (of 0.6% between January and April 2021), whereas second-hand house prices continued to eke out moderate growth (0.7%). This suggests a degree of retrenchment with respect to new housing developments in an environment of uncertainty for construction, with more limited effects on existing houses.

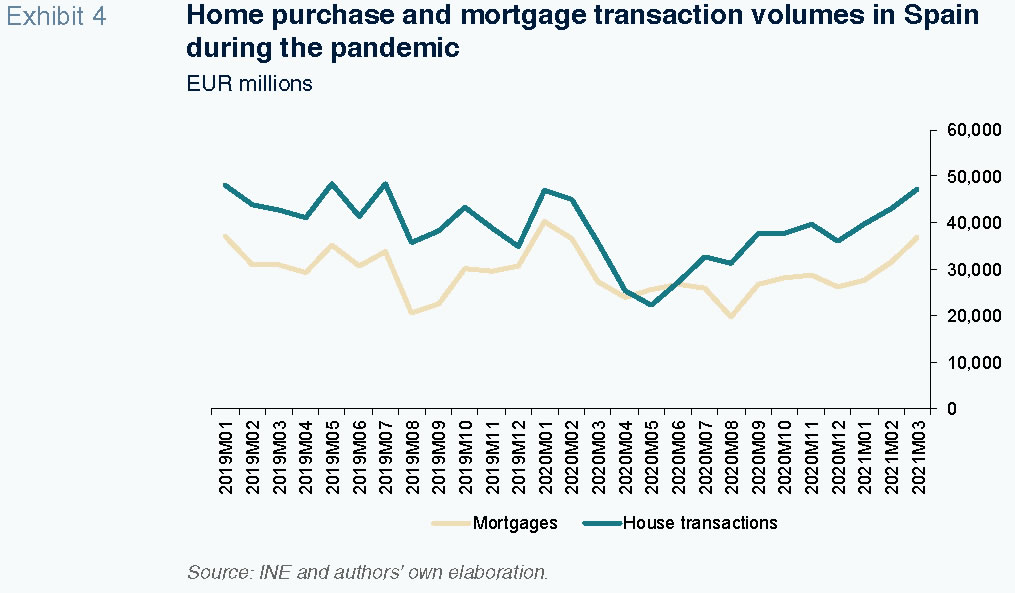

In order to assess what has happened in transaction volumes and mortgage lending, Exhibit 4 compares the number of mortgages and home sales. The first point to note is that both transaction and mortgage volumes are returning to pre-pandemic levels, although the recovery has further to run in 2021 and 2022. Secondly, the number of transactions is significantly higher than the number of mortgages arranged. Although the correlation is imperfect, it suggests that a lot of the transactions are not being carried out by households in need of financing but rather investors (including institutional investors) that can afford to pay for their acquisitions without relying on a mortgage.

The pandemic has probably had a bigger impact on the rental market than on home ownership as the restrictions on mobility and the remote working phenomenon have boosted rental vacancies and fuelled price cuts. Although there are no official statistics, certain online portals such as Fotocasa maintain that rents may have fallen by around 8% or 10% in Madrid and Barcelona during the pandemic. That same platform estimates that despite the appearance of some recovery early on in the year, rental prices in Spain ended May at 10.42 euros/m

2, which is down 0.2% from April, marking the fourth consecutive month of price correction.

The pandemic has also slowed the momentum in holiday home rentals. This is likely due to lockdowns and mobility restrictions.

According to the INE, in February 2021, 294,698 such homes were listed on online platforms, homes with a total of 1,495,578 places (an average of 5.1 per house). By comparison with August 2020, the number of holiday home listings has fallen by 8.3%. The regions with the highest number of listings are Andalusia (61,574), Catalonia (54,646) and Valencia (49,757).

Conclusion: Housing policies and forecasts

Although the figures suggest the pandemic has had a limited impact on the property market, with transactions slowing and price growth easing, the ad-hoc eff of lockdowns, namely mobility restrictions and job losses, have once again shone the spotlight on aff issues that Spain had already been wrestling with before the onset of COVID-19. As a result, the Spanish government has opted to extend some of the relief measures put in place for more vulnerable groups of the population. In the rental market, tenants can ask for an extraordinary extension of their lease agreements for up to six months which landlords are obliged to accept on the same terms as the existing agreement, unless they can substantiate they need the property for their own use. It has also extended the stay on evictions and foreclosures until August 9th and rolled over the measures for the deferral of rent for vulnerable households who rent from companies, public entities or large landlords. The temporary financing aid in the form of loans guaranteed by the Official Credit Institute, ICO, for low-income tenants (interest- and commission-free loans with a maturity of between six and ten years) has also been extended. The size of those loans is up to 100% of six months’ rent under lease agreements for primary residences, with a ceiling of 5,400 euros, or 900 euros per month.

As for the market outlook, the growth in average unsubsidised house prices is estimated at around 1% in 2021, with a slightly stronger performance of 1% to 2% forecast for 2022. The construction industry looks set to receive a boost in the months to come with up to 1 billion euros of funds from the Recovery and Resilience Facility earmarked to residential building refurbishment and energy conversion.

There is also talk of a number of different initiatives to alleviate the housing affordability problem, particularly in regions characterised by scarce supply and high prices. There are initiatives afoot under the umbrella of the State Housing Plan in collaboration with the regional and local governments to make publicly developed housing available for rent. The Ministry of Transport, Mobility and Urban Agenda, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Digital Transformation and SAREB, Spain’s so-called bad bank, have entered into an agreement to make 5,000 new homes, extendible to 10,000 in the medium-term, available to the regional and local authorities. The Ministry will partially bear the costs of the transfer, refurbishment and work needed to guarantee the habitability of the homes. Those homes will be leased at discounted rents to people facing affordability problems.

There is less agreement about the advisability of rent regulations. The evidence gleaned from the leading academic studies and recent experiences in other European countries is that rent controls and regulations tend to lead to counter-productive decreases in supply and increases in prices.

Notes

For more information about the variety of statistics and their limitations, refer to Carbó Valverde and Rodríguez Fernández (2015).

References

Santiago Carbó Valverde and Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas