A snapshot of Spain’s mortgage market

The notable recovery in Spain’s housing market is bringing some relief to both banks and households. While the pick-up in the sector has raised concern over whether or not the country is once again building up imbalances, at present there is no clear evidence to support that a property bubble is forming.

Abstract: Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, 20% of every 100 euros of housing loans extended in the eurozone were granted in Spain. Today, five years after the country’s real estate bubble burst, that percentage stands at 5.2%. The housing market is recovering, however, with new housing loans registering double-digit year-on-year growth since April 2018. This has sparked renewed interest in how Spain’s mortgage market compares to other eurozone economies, from business indicators to interest rates to borrowing terms and conditions, bank margins, rejection rates and household debt service ratios, among other indicators. While there has been a notable pick-up in Spain´s mortgage market, the volume of mortgages granted, the size of new mortgages and the financial burden for households are all well below the highs of the past and there are no clear signs pointing to the emergence of another property bubble.

IntroductionIn 2006, at the height of the real estate bubble, mortgages in Spain peaked at 1,342,171 and loans to households for house purchases (mortgages or housing loans) totalled 170 billion euros. After the bubble burst, the number of mortgages plummeted, bottoming out at 199,703 in 2013 (down 85% from 2006). That year, the value of the mortgages extended by Spanish banks amounted to 21.86 billion euros (down 87% from 2006). Since then, the housing market has been recovering little by little, and in 2017 the number of mortgages rose to 312,843. In the first three quarters of 2018, that figure increased 9.7% year-on-year and the value of new loans climbed 14.4% year-on-year to 32.43 billion euros.

[1]

While Spain’s mortgage market is recovering, we are still very far from the business volumes observed before the crisis. In fact, Spanish banks currently account for 5.2% of mortgages granted for the purchase of homes in the eurozone, significantly below its 20% share in 2006. The recovery in house prices and mortgage volumes in recent months (new mortgages are growing in the double digits) has sparked renewed interest in analysing this segment of the loan market. As the banking crisis and excesses of the past fade from view, we can now take a fresh look at how Spain’s mortgage market compares to other eurozone economies, from business activity to interest rates, borrowing terms and conditions, bank margins, rejection rates and household debt service ratios and other indicators.

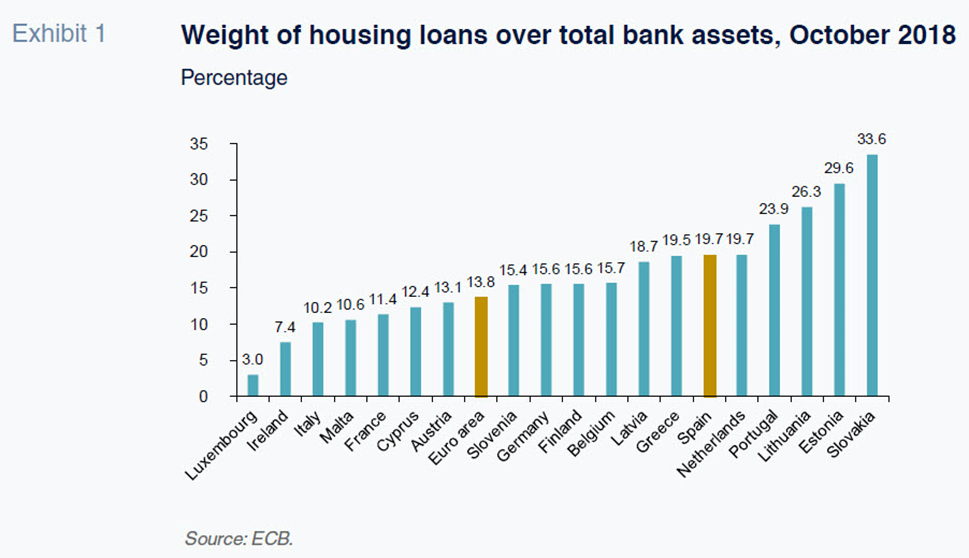

Business activityThe Spanish banking sector ranks sixth in the eurozone in terms of mortgages over total assets (Exhibit 1), a sign of the importance of this segment to Spanish banks’ business. Mortgages currently account for 19.7% of the Spanish bank sector’s assets, which is 5.8pp above the eurozone average and above the levels observed in the main European economies (10.2% in Italy, 11.4% in France and 15.6% in Germany). The overall stock of mortgages stands at 519 billion euros, making Spain the third largest market in size, behind only Germany and France. The mortgage pool peaked at 665.2 billion euros at the end of 2010, but since then has contracted by 22%. Following this contraction, the market has returned to its size in 2006.

Although the deleveraging process began in 2010, the pace of growth had begun to slow much earlier, in the middle of 2006, when the market was expanding at an annual rate of 35% or nearly triple the eurozone average. Growth in the Spanish mortgage market has been trailing that of the eurozone since 2009 (the lag peaked at nearly 7pp at the end of 2017). Although the gap has been narrowing, it remains at 4.7pp. Whereas the eurozone mortgage market registered growth of 3.3% between October 2017 and October 2018, in Spain the market contracted by 1.4%. The contraction in Spain contrasts with expansion of 4.8% in Germany, 7% in France and 1.3% in Italy.

Although the stock of mortgages continues to fall in Spain, new housing loans have been registering strong growth in recent months. Spanish banks extended 14.8% more new housing loans year-on-year in the 12 months to October 2018 and growth has been in the double digits since April of that year. Again, this trend contrasts with that of the eurozone, where new mortgages (trailing 12 months) have been contracting since the end of 2017. By market, new mortgages are contracting in France and Italy and registering modest growth of just 1.7% in Germany. Between November 2017 and October 2018, Spanish banks extended mortgages totalling 43.5 billion euros.

Since the end of 2017, a higher percentage of banks report that demand for mortgages is growing than report the opposite, with a net percentage of 21pp in the second quarter of 2018, albeit falling to 3.4pp in the third quarter. According to Spanish banks, stronger consumer confidence and low borrowing costs and house prices are the factors contributing to increased demand for mortgages.

Interest rates

The rate of interest charged on loans for house purchases has generally tended to be lower in Spain than in the eurozone, typically by around 100 basis points (bp). That spread has narrowed somewhat in the last three years, but remains at 91bp today. The average rate of interest charged on mortgages was 1.21% in Spain as of November 2018 versus 2.12% in the eurozone (Exhibit 2b). That is lower than the rates charged in all the major European bank sectors: 2.45% in Germany, 1.98% in France and 2.01% in Italy. Among the eurozone countries, only Portugal and Finland boast lower mortgage interest rates than Spain.

The situation changes when we look at the new loans being extended by banks rather than the prevailing average rate on the stock of outstanding mortgages. By that measure (November 2018), the rate currently charged in Spain is slightly above the eurozone average (19bp higher): 2.02%

versus 1.83% in the EMU (Exhibit 2a). The Spanish banks are setting a higher rate of interest on new mortgages than their counterparts in Italy (1.91%), Germany (1.88%) and France (1.5%), within an interval marked by two extremes: Greece (3.34%) and Finland (0.89%). Since the middle of 2012, the rates charged in Spain have been very similar to the eurozone average.

Bank margins

The trend and level of margins applied by Spanish banks on mortgages compared to the average (unweighted, as the ECB does not provide the figure for the EMU) for the eurozone bank sectors are related with the interest rate analysis above. Thus, margins have been relatively similar since 2014. They have been largely stable for the last three years at around 180–190bp. The most recent figures (dated October 2018) show a margin in Spain of 190bp, which is 10bp above the eurozone average. Of the 19 EMU countries, Spain ranks thirteenth in terms of margins applied, ahead of Italy (121bp), France (127bp) and Germany (176 bp).

Fixed versus floating rates

Another area of interest when analysing the mortgage market is fixed versus floating interest rates. With the sharp drop in the ECB’s benchmark rate to address the recent crisis (Euribor has been in negative territory since 2016), there is now greater incentive to apply for fixed-rate mortgages to hedge the risk of rate increases in the future. This phenomenon is very evident in Spain: since September 2008, when the ECB began to cut its benchmark rates, the percentage of floating-rate mortgages has fallen by over half, from 90% to 38% by October 2018. The weight of floating-rate mortgages has also fallen in the eurozone on average, although less intensely: from 34.5% to 19.2%. In Spain, floating-rate mortgages have always been in the majority, although this has corrected sharply to move closer in line with the eurozone, particularly since 2012. Since January 2018, the difference has been less than 20bp and since August 2017 fixed-rate mortgages have predominated.

Compared to the rest of the eurozone countries, the percentage of floating-rate mortgages in Spain (38%) is higher than in the biggest economies (30.2% in Italy, 11.5% in Germany and 2.2% in France). This percentage stands at over 90% in Cyprus, Latvia, Finland, Lithuania and Poland.

Non-performing loans

In Spain, non-performance has always been significantly lower on housing loans than in other loan segments, although it has been affected by the economic cycle. This ratio rose from under 1% in 2007, before the start of the crisis, to a high of 6.3% in March 2014 (which was less than half the level of 13.6% at which the NPL ratio peaked for the private residential sector), going on to trend lower to 4.4% in June 2018, 1.9pp below the overall private sector NPL ratio. Of all non-performing loans on the Spanish banks’ books, 29% (23.1 billion euros) are now mortgages, the same percentage as in March 2008, before the crisis.

Loan approval criteria

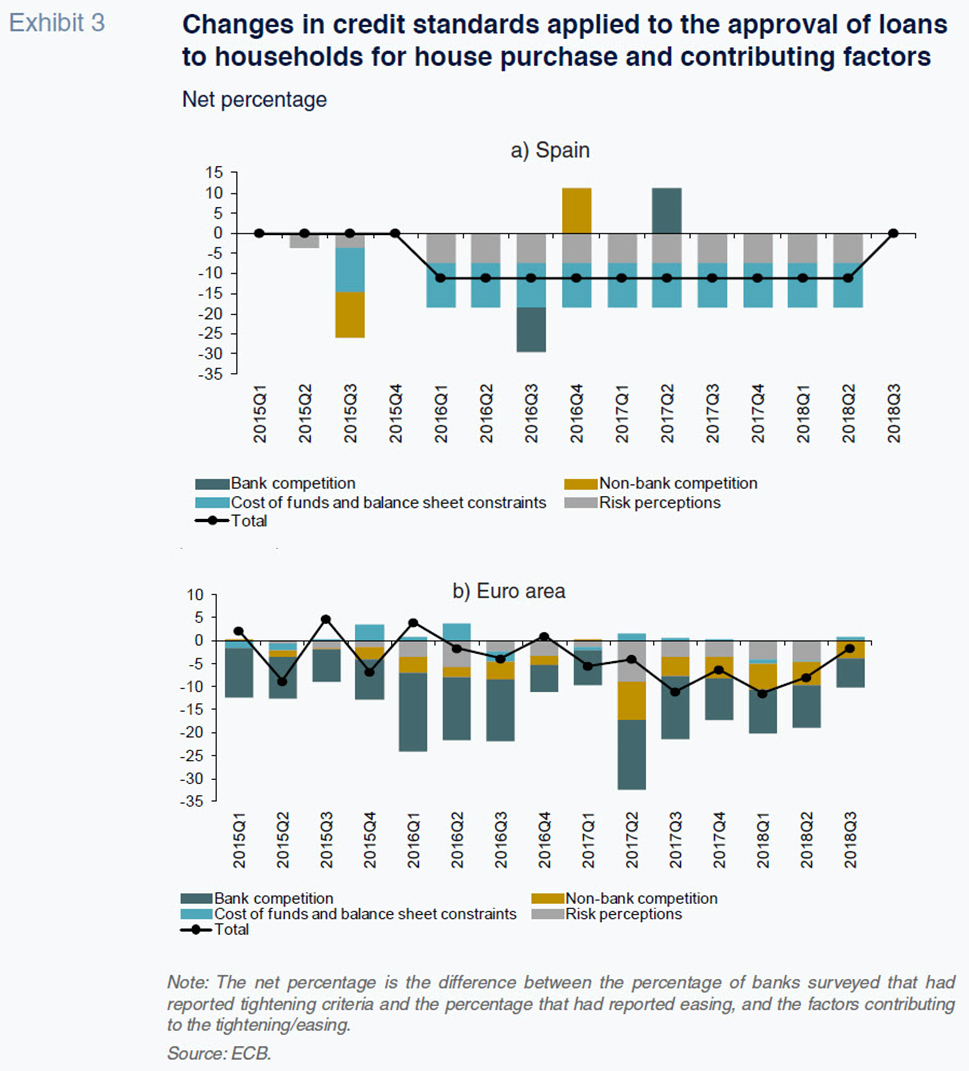

For two and a half years (from early 2016 until the middle of 2018), Spanish banks have been easing the credit standards used to approve mortgages, as the percentage of entities that reported an easing of their criteria to the ECB was 11pp higher than those that had reported a tightening (Exhibit 3). In the third quarter of 2018, the net percentage of responses is zero. Compared to the eurozone average, that easing started sooner in Spain and has been somewhat more intense.

Since 2016, the factors contributing to the easing of the housing loan approval criteria used by Spanish banks have been a perception that transaction risk has diminished and an improvement in the banks’ access to financing. In contrast, in the eurozone, the same trend has been driven above all by growth in competition (from other banks but also from non-banks), but also by a perception of diminished risk.

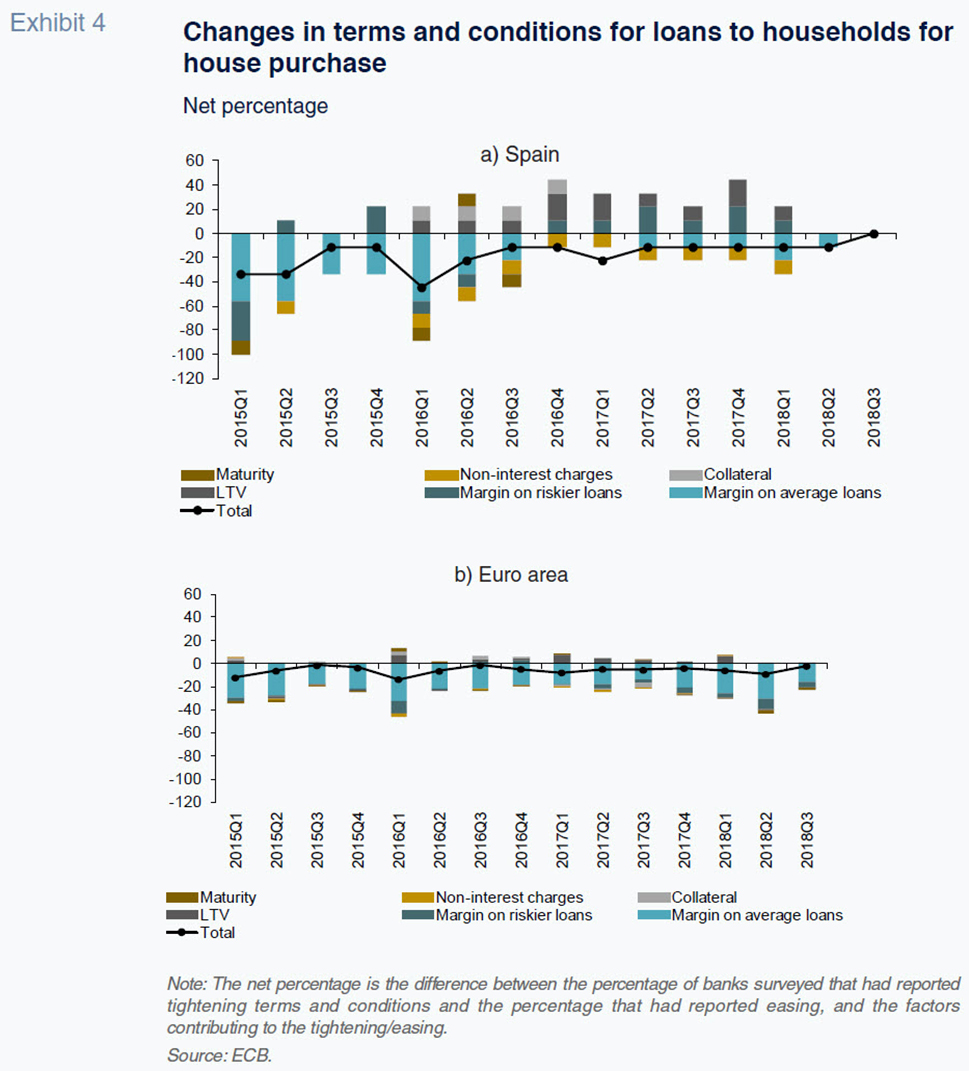

Housing loan terms and conditionsAs Spanish banks have eased their mortgage approval criteria in recent years, they have also been easing loan terms and conditions. Again, they began to do so much sooner and with far greater intensity than their eurozone peers. The improvement has materialised in both the margins applied and in non-interest rate charges (fees and commissions). In contrast, they have become more stringent with collateral, especially loan-to-value (LTV) demands. They are also applying higher margins to riskier loans. By comparison, the easing in the terms and conditions applied by eurozone banks has been shaped primarily by a reduction in margins. However, the scope for improving mortgage terms and conditions appears to be declining: in the third quarter of 2018 (the last ECB bank lending survey conducted), the net percentage of responses was 0 in Spain and −2pp in the eurozone (Exhibit 4).

Mortgage rejection rate

The housing loan rejection rate is another indicator providing valuable information about changes in the banks’ willingness to award mortgages. In Spain, as of the third quarter of 2018, 11pp more banks reported easing their rejection rate relative to those that reported the opposite; the net percentage has been negative nearly every quarter for years. In the eurozone, the net percentage also used to be negative, but less so. However, in the last two surveys conducted in 2018, the net percentage was positive, at 3pp in the most recent quarter. These figures therefore confirm the relatively greater intensity with which Spain is easing access to mortgages, with the percentage of banks reporting higher mortgage application approval rates continuing to outweigh the percentage reporting higher rejection rates.

Mortgage debt service

The recovery in the mortgage market also depends on the debt service burden for the borrower, which depends on several factors: the rate of interest on the loan, the non-interest rate charges (fees and commissions), the amount to be repaid each year and their disposable income. The lower the debt service ratio, the higher, in theory, the demand for mortgages and the lower the transaction risk for banks.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has been estimating and tracking the household debt service ratio quarterly for selected countries, including Spain, since 1999. According to its figures, Spanish households had to earmark 11.9% of gross disposable income to servicing mortgages as of September 2008. The peak hit at the height of the crisis when households were highly leveraged, but since then the debt service ratio has been coming down slowly, bottoming out at 6.6% in March 2018 (latest figure available), a return to 2003 levels.

In 2018, Spanish households’ debt service ratio was similar to that of their counterparts in Germany (6.1%) and France (6.2%), higher than that of Italian households (4.4%) and lower than that of households in the UK (9.4%) and the US (8.2%). Spain stands out globally as one of the countries where the household debt service ratio has fallen most sharply since the 2008 financial crisis. In fact, of the countries tracked by the BIS series, this ratio has fallen by more only in Denmark: 7.5pp compared to 5.3pp in Spain.

Conclusions

- Although the stock of mortgages continues to decline in Spain, new housing loans are recovering, registering double-digit year-on-year growth since April 2018. Despite this growth, the volume of loans extended during the last 12 months (43.5 billion euros) was only a quarter of the volume extended at the peak of 2006, demonstrating that we are still far from bubble-level business volumes. Back then, 20% of every 100 euros of housing loans extended in the eurozone were granted in Spain; today, that percentage stands at 5.2%.

- Although the rate of interest charged on new mortgages is slightly above the eurozone average (2.02% vs. 1.83%), the average rate on outstanding stock on the banks’ books is less (1.21% vs. 2.12%).

- The margin applied by Spanish banks to mortgages has been relatively stable since 2014 and is now similar to the average in the eurozone (just 10bp higher).

- The sharp drop in benchmark interest rates has stimulated a drastic change in the mortgage mix, with the weight of floating-rate loans falling from 90% in 2008 to 38% in 2018. That percentage remains higher than in the main European economies.

- The information provided by the bank lending survey conducted regularly by the ECB clearly shows that the terms of access to mortgages have improved considerably in Spain, even though the banks are now demanding more collateral and charging higher commissions. In parallel, the banks have eased their loan approval criteria and lowered their loan rejection rates

- Spain stands out in the world as one of the countries where the household debt service ratio has fallen the most: in 2018, Spain’s households had to earmark 6.6% of their disposable income to debt servicing (interest expense and principal repayments), 5.2pp less than in 2008.

- Although house prices are recovering, Spain is still far from the levels seen when the real estate bubble burst. In addition, the volume of mortgages granted, the size of new mortgages and financial burden implied for households are all comfortably below the highs of the past. As a result, the overall snapshot gleaned from the universe of available indicators is that there are no objective reasons to believe that a property bubble is forming.

Notes

This paper falls under the scope of research project ECO2017-84828-R under the Spanish Ministry of the Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.

Joaquín Maudos. Professor of Economic Analysis at the University of Valencia, Deputy Director of Research at Ivie and collaborator with CUNEF