The greening of the ECB

Christine Lagarde has signaled her desire to ‘green’ the European Central Bank (ECB), a statement that has both garnered applause from climate change activists and alarmed orthodox monetarists. While the ECB does have a dual mandate and numerous instruments at its disposal to achieve Lagarde’s objectives, there is concern that such actions could undermine the political independence of the central bank.

Abstract: Incoming ECB President Christine Lagarde has signaled a commitment to ‘green’ the ECB. In this regard, the ECB could potentially support efforts to adapt to climate change through changes to supervisory requirements, credit rating agencies’ methodologies, and/or its own formulas for macro-prudential supervision. It could even intervene in financial markets under a ‘green’ asset purchase program, however this could potentially create distortions, while effectiveness would be conditioned on the timing of such programs. The institution could even consider the use of its own investment portfolio to meet such objectives, creating a signalling effect. Nevertheless, to date, former ECB presidents have interpreted this dual mandate as prioritizing price stability over any economic policy objective. Thus, critics have expressed concern that going beyond that, i.e., with the ECB’s foray into climate change activism, could undermine the political independence of the central bank.

Introduction

Christine Lagarde is not Mario Draghi. She admitted as much in her first encounter with the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee of the European Parliament. During the question and answer session, she joked with committee members that she is still learning German and hopes one day to be able to answer their questions in that language. She also joked that she is still learning to speak like a central banker. That language is very precise, she insisted:

“So bear with me, show a little bit of patience, don’t over-interpret, if I may say so. I will have my way of also addressing some of the key issues that have to do with monetary policy.” [1]

Lagarde repeated this theme in her first press conference last December. She told the assembled journalists that they are an important audience, but that she also must speak to a wider public. She explained that this is likely to create confusion, particularly as she acclimates to her new position. And she admitted that she has not yet mastered the many details related to the conduct of monetary policy or the deeper infrastructure that underpins European financial markets. She is learning, but by her own admission, she is not there yet.

[2]

Lagarde’s rhetoric reveals her intentions both to disarm her critics and to achieve her central objective — to bring the European Central Bank closer to the people of Europe; to make the ECB more relatable and more transparent; and to help the people understand both not just that monetary policy is ‘important’, but that it is also relevant. As Lagarde deepens her knowledge of monetary policy, so will the rest of Europe.

The fight against climate change is another tool that Lagarde has at her disposal. During her confirmation hearings before the European Parliament last October, Lagarde announced her intention to use whatever instruments the ECB has at its disposal to help ‘in sustaining global cooperation’ to prevent climate change.

[3] She reiterated that commitment when she testified before the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee and again in her press conferences in December and in January. Moreover, she has linked this commitment to a strategic review of the conduct of monetary policy — putting everything on the table, including the definition of the ECB’s policy objective.

This commitment has attracted considerable attention.

[4] It has also created some uncertainty in the markets about what the ECB can do and how much that effort might change (or challenge) the conduct of monetary policy. That uncertainty revolves around three issues: the ECB’s mandate; its instruments together with its functioning as an institution; and its political independence.

The ECB’s dual mandate

The Statute of the ESCB agreed at the time of the Maastricht Treaty gives the European Central Bank a dual mandate with a clear hierarchy. As Article 2 of the Statute makes clear:

"The primary objective of the ECB shall be to maintain price stability. Without prejudice to the objective of price stability, it shall support the general economic policies in the Union with a view to contributing to the achievement of the objectives of the Union as laid down in Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union." [5]

When that Statute was drafted, Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union (originally numbered Article 2) included a broad range of issues running from cohesion across countries to sustainable growth and employment. In the years that preceded the start of Europe’s economic and monetary union, the European Council continued to broaden the range of economic policy objectives. Meanwhile, the Council of Economic and Finance Ministers (ECOFIN Council) gave more precise structure in the elaboration of Broad Economic Policy Guidelines as part of the pattern of macroeconomic policy coordination.

The problem for the first ECB Governing Council as it began to meet in 1998 just prior to the launch of the single currency was to choose between the ever-widening policy objectives set out in the Treaty (and referred to by the Statute) or the more precise policy guidelines set out by the ECOFIN Council. It was also to decide how to explain which of the Broad Economic Policy Guidelines the ECB would support provided it had met its objective of price stability.

For then German Finance Minister Oskar Lafontaine, this problem was not theoretical. He wanted the ECB to focus on unemployment and to lower interest rates accordingly (Jones, 2000). This brought Lafontaine into conflict with then ECB President Wim Duisenberg. Duisenberg was uncomfortable announcing that the ECB had achieved price stability when the Governing Council was still trying to understand the new aggregates used to measure price inflation across the monetary union and when it was only just starting to experiment with a dual approach to defining what price stability means, using both expected inflation over the medium-term and a targeted growth rate for the broad monetary aggregate (M3). In response to Lafontaine’s insistence that the ECB do more to tackle unemployment as part of its dual mandate, Duisenberg argued that the ECB’s contribution to the European Union’s broader economic objectives is the achievement of price stability:

“A climate of price stability is the best thing we can deliver; and to the extent that we deliver price stability, then, as the Treaty says, without prejudice to the price stability, monetary policy should and will contribute to the other economic roles as specified in Article 2 [now Article 3] of the Treaty on European Union.” [6]

Duisenberg reiterated that argument about the ECB’s dual mandate throughout his time as ECB president and long after Lafontaine resigned from the German Finance Ministry. Moreover, both Jean-Claude Trichet and Mario Draghi picked up on that refrain. In this way, successive ECB presidents tied the two sides of the ECB’s dual mandate together so tightly that it became easy to ignore the fact that the ECB even has a dual mandate. Instead, it became commonplace to assert that the ECB’s mandate is to secure price stability.

This tension shows up clearly when Lagarde talks about the possibility for the Governing Council to support the Green Deal of the European Commission. On the one hand, Lagarde is quick to point out that such support is possible insofar as the ECB has a dual mandate. On the other hand, she is quick to insist that the ECB’s mandate is to ensure price stability.

For those who worry most about fighting climate change, only the broader mandate is important. They want to see how much and how quickly the ECB can throw its weight behind their goals. Their goal is to encourage Lagarde to take action. For those who focus more narrowly on price stability, the question is how to enforce this priority. Even accepting that the dual mandate allows the ECB to support the broader economic policies of the European Union, they want a clear sense of how the Governing Council will know it has achieved the goal of price stability; they also want to know how the Governing Council should determine whether efforts to support the fight against climate change will not get in the way of that objective.

A choice of instruments

The debate between climate change activists and orthodox monetarists has a technical dimension insofar as it touches on the whole range of instruments deployed by central banks, including the ECB, from financial supervision to outright asset purchases and open market operations. Each of these instruments has a powerful impact on the financial economy. As a result, each is also surrounded by controversy. Hence the opportunities for effective central bank involvement are more limited than many might anticipate (Honohan, 2019).

For example, the ECB can support efforts to adapt to climate change by requiring banks to build climate risks into their supervisory requirements; the ECB can also encourage other financial market participants like credit ratings agencies to make the role of climate risks more explicit in their analysis; and, it can add climate risks to the formulas it uses for broader financial stability planning or macro-prudential supervision. Such actions will create incentives for financial institutions to reallocate their portfolios away from assets that foster climate change and also from assets that are exposed to the negative consequences of any damage done to the environment — and toward assets that help to mitigate climate change or to respond to any necessary adaptation or adjustment. The question here is whether the regulators, the credit ratings agencies, or the financial institutions fully understand the risks involved in a process so large and so complex. There is good reason to believe they do not – in which case, the first requirement is to begin sorting out what kind of modeling or conceptual foundations are necessary to differentiate between how different firms are exposed to potential losses and what kind of systemic implications such losses entail (Bolton et al., 2020).

The ECB can also intervene more directly in financial markets. For example, the Governing Council can lower the haircuts charged on (or reduce the eligibility requirements for) ‘green’ assets pledged as collateral in routine financial operations. Alternatively, the Governing Council can skew the structure of its direct asset purchases away from ‘brown’ industries and toward assets created to support ‘green’ finance initiatives. As Lagarde has been quick to admit, however, the challenge in this area is three-fold:

- First, the European Commission has not come out with a clear ‘taxonomy’ of which assets are ‘green’, which are ‘brown’, and which fall into the shades in between. Moreover, this taxonomy is not a simple matter of categorizing the firms that create these assets: even otherwise ‘brown’ firms are involved in ‘green’ ventures and so it is important ‘to be extremely granular’, borrowing one of Lagarde’s phrases, in examining the uses of the asset in order to avoid creating perverse incentives. [7] There has been progress made in negotiations between the Council and the European Parliament, but the final legislation is still to be completed and will not come into effect until the end of 2021. [8] Hence, relying on the commercial paper side of the ECB’s asset purchasing program is anything but straightforward.

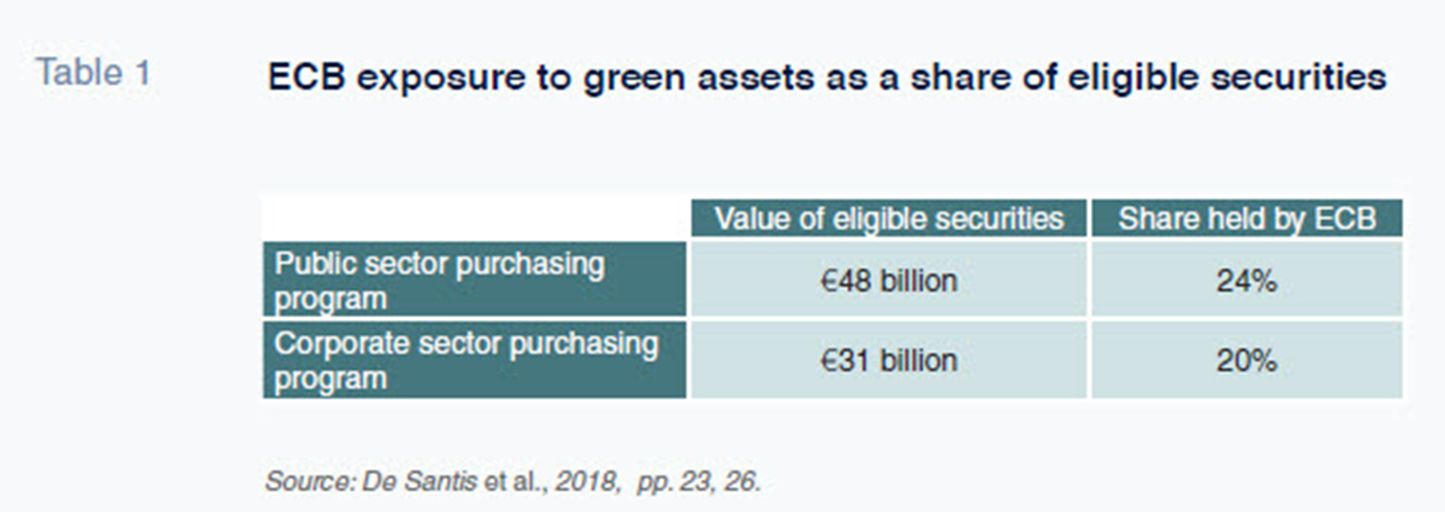

- Second, the European Central Bank has a responsibility to avoid creating market distortions and the supply of tailor-made ‘green’ assets is simply to small for the ECB to intervene in an effective manner. The bank has already purchased some of these assets, both from the corporate sector and from the official sector, including the European Investment Bank; indeed, analysis published by the ECB in 2018 shows that the percentage of ‘green’ assets already acquired is on a par with ECB holdings of other assets (De Santis et al., 2018). Doing any more would threaten to distort markets. Worse, there is little evidence that it will generate much of a positive effect in terms of relative financing costs (Honohan, 2019).

- Third, the large-scale asset purchasing program is designed to be temporary rather than permanent. At some point in the future, the ECB will seek to scale down its balance sheet as part of the normalization of monetary policy. In turn, this will require the ECB to scale down both the net purchases and eventually also the holdings of any green assets. By implication, the effectiveness of any ECB intervention through outright purchases will be only temporary as well and also subject to reversal. These actions may be unpopular –particularly among climate activists, as noted by Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann– but, as Lagarde has insisted repeatedly, the ECB’s responsibility for price stability comes first. [9]

Another instrument that the ECB could consider is its own investment portfolio –meaning, not the balance sheet that it holds for the Eurosystem as a whole, but the assets it acquires to fund operational expenses, pensions and the like. These ‘other assets’– in the language of the ECB’s annual report

– are worth roughly €20 billion. Their purpose is to maximize risk-weighted return in order to ensure that the ECB meets its financial obligations as reported in profits and loss. Just over 60 percent of these assets have a maturity of one year or more (ECB, 2019). And, Lagarde has suggested, it should be possible to skew the distribution of this portfolio toward the acquisition of ‘green’ assets:

“[W]e clearly also have to include climate change imperatives in our investment operations –the ones we do for our own portfolio– and we also have to include that in the management of the pension fund.” [10]

Such a change in the investment of ‘other assets’ would not implicate the conduct of monetary policy but would instead touch upon the ECB as an institution. The result would not be as dramatic as further operations on the balance sheet for monetary policy operations, but it would be non-negligible. As Lagarde put it in her January press conference: “small rivers make very large oceans eventually when they are protected.”

[11] To give a sense of the relative magnitudes, Table 1 provides estimates from the ECB of the total stock of ‘green’ assets eligible for inclusion in both the corporate sector asset purchasing program and the public sector asset purchasing program together with the percentage already held by the ECB on its monetary policy portfolio. The scale is closer to the size of the ‘other assets’ portfolio than might be imagined. Moreover, such a change in investment policy would send an important signal of the ECB’s determination –as an institution– to lend its weight to the fight against climate change and to set an example for others to follow.

Political independence

The symbolism of directing the ECB as an institution would fit well with one of the key objectives of Lagarde’s agenda – to bring the institution closer to the people. Indeed, it would work much better than any attempt to qualify the use of monetary policy instruments with the goal of underpinning green finance. Most importantly, such an act would help to insulate the ECB from engaging too openly in distributive politics. If the Governing Council can use its large scale asset purchasing program to nurture green finance, then it could also use its balance sheet to encourage greater regional cohesion or social solidarity – two goals that lie at the core of the broader economic objectives in the Treaty on European Union and that have been decided time and again by European institutions.

The problem is that even a marginal use of the ECB’s monetary instruments to support other economic objectives opens a Pandora’s box of political considerations. That is why successive ECB Presidents have chosen to tie the two sides of the bank’s mandate so closely together. It is why Jens Weidmann expressed concern that “a monetary policy which pursues explicitly environmental policy objectives is at risk of being overburdened.”

[12] And it is why Lagarde “agree[s] with Mr. Weidmann” that “we can be effective in participating in the fight against climate change … [but] this … does not turn us into having, as mandate number one, the fight against climate change.”

[13] The ECB can help improve the models that are used to understand the risks involved, it can look at the margins of its monetary policy activities to see where they might have some positive influence, and it can commit itself as an institution to set an example and to serve as a focal point for coordination.

Doing any more than that, however, would bring the ECB into the realm of political decision making and it would jeopardize the bank’s political independence. The result would be to make the ECB more controversial and not less. It would also make it harder for European citizens to understand why the Governing Council is doing what it is doing. These things all run against one key element of Lagarde’s agenda – bringing the ECB closer to the people.

By contrast, relying more heavily on symbolic and institutional commitments pushes in the opposite direction. As the former Irish Central Bank Governor Patrick Honohan (2019) argues:

“Central banks that have bought private securities as part of their monetary policy are behind the curve… and, in their attempt to be market neutral, risk being seen as opposed to a growing consensus for the need for private and public actions to address climate change. The opportunity for signaling endorsement of this consensus has not yet been seized. To protect their public standing they should seek a way of rejoining a more centrist position…; this too should be possible without compromising their independence from government—and indeed could ultimately strengthen broad support for that independence.”

Honohan suggests that this more centrist position could be in the form of “any new round of asset purchases” (which is the text removed in the second ellipsis). Since the goal is symbolic, however, a clear institutional commitment to greening the ECB may offer better signaling. Indeed, that seems to be where Lagarde is headed.

Notes

‘Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs,’ p. 17.

Weidmann’s speech on climate change, given in Frankfurt on 29 October 2019, is available here: https://www.bis.org/review/r191029a.htm. See also Martin Arnold and Olaf Storbeck, ‘Weidmann opposes using monetary policy to fight climate change,’

Financial Times (29 October 2019)

https://www.ft.com/content/60d9832c-fa3f-11e9-a354-36acbbb0d9b6. Lagarde’s response to this argument came in the question and answer from her hearing before the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee of the European Parliament. See, ‘Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs,’ pp. 13-14.

Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs,’ p. 14.

‘Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs,’ p. 13.

References

BOLTON, P. et al. (2020). Central Banking and Financial Stability in the Age of Climate Change. Basle: Bank for International Settlements.

DE SANTIS, R. A., et al. (2018). Purchases of Green Bonds under the Eurosystem’s Asset Purchase Programme. Economic Bulletin, No. 7. Frankfurt: European Central Bank, pp. 21-27.

ECB. (2019). Annual Accounts of the ECB 2018. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

HONOHAN, P. (2019). Should Monetary Policy Take Inequality and Climate Change into Account?’ PIIE Working Paper 19-18. Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics (October).

JONES, E. (2000). The Politics of Europe 1999: Spring Cleaning. Industrial Relations Journal, 31(4), pp. 247-261.

Erik Jones. Professor of European Studies and International Political Economy at the School of Advanced International Studies of The Johns Hopkins University