Spanish banks ahead of MREL:

Estimating projected issuance for compliance

In response to greater regulatory clarity and favourable market conditions, Spanish banks have already issued over a quarter of their MREL requirements in 2017. The outlook for issuance remains constructive in the coming year, although there is still scope for adjustment to ultimate outstanding MREL funding needs.

Abstract: Having digested the new capital requirements imposed under Basel III, banks are now facing requirements to have easily ‘bail-inable’ instruments for loss absorption purposes in the event of resolution under the so-called Minimum Requirement of Eligible Liabilities (MREL). In recent months, progress has been made on specifying MREL requirements for European banks, and providing sufficient detail to allow for an estimation of Spanish banks’ associated funding requirements for MREL compliance. Based on year-end 2016 data, we estimate an issuance requirement of between 65 and 79 billion euros. Over one-quarter of required issuance was already covered in 2017 in a very propitious market for ‘bail-inable’ liability issues, principally for senior ‘non-preferred’ notes – instruments that have been specifically regulated in Spain (June 2017) as particularly appropriate for the purpose of meeting MREL requirements. Going forward, strong investment appetite and constructive market conditions should underpin continued issuance at favourable terms of the remaining MREL requirements for Spain’s significant banks in the coming year. However, the final levels of bail-inable capital needed for MREL compliance may still vary given that numerous parameters of the regulations have yet to be defined, together with the entity-specific approach taken by European authorities.

MREL: A complement to capital requirements

In order to shore up the new capital requirements imposed by the new Basel III framework in response to the financial crisis, international banking regulations, and European regulations in particular, have introduced additional requirements regarding the composition of banks’ liabilities, specifically the need to have liabilities capable of absorbing losses in the event of resolution.

The rationale for the new requirements lies with an attempt to avoid the massive injections of public capital that numerous countries –not only Spain but virtually every country in Europe and the United States – incurred in the wake of the banking crisis between 2008 and 2012, with the ultimate aim of preventing such a situation from happening again. A first step in this direction is the requirement to hold more and better quality capital, these being the two basic tenets of the new Basel III framework, as outlined by Rojas, Sánchez and Valero in a previous paper for this same publication.

However, it is not just about holding more capital. In addition, banks have to have a second line of liabilities that, without strictly qualifying as capital, can be readily used to absorb losses and to recapitalise the bank once it emerges from resolution.

In short, the idea is to lay the foundations so that in the event of future banking crises, the cost of recapitalisation (and the absorption of the losses preceding that recapitalisation) is shouldered by the banks’ own creditors (‘bail- in’), minimising the need to call on taxpayers (bail-out), so massively resorted to during the last crisis.

It is with this objective in mind that the international regulatory authorities (specifically, the Financial Stability Board or FSB) developed the Total Loss Absorption Capacity (TLAC) concept for systemically important institutions; and in the case of Europe, what is known as Minimum Requirement of Eligible Liabilities (MREL), which is applicable to all European banks unless it is assumed that they would be liquidated on account of not performing a critical function in the financial system. Given that it will be required of virtually every European bank, in this paper we focus on MREL, the progress being made on its defi how Spanish banks are positioned in terms of complying with it and the issues we have been seeing recently in an attempt to advance towards compliance.

In this respect, it is important to note that numerous parameters of MREL have yet to be specified. In fact, the requirements will entail an element of the ‘bespoke’, entity by entity, approach, depending on resolution strategies and systemic importance (their ‘resolvability’), which in all likelihood will not be disclosed by the supervisors. Notwithstanding these unknowns, there is enough information to estimate the approximate magnitude of the funding requirement.

Defining MREL, new developments

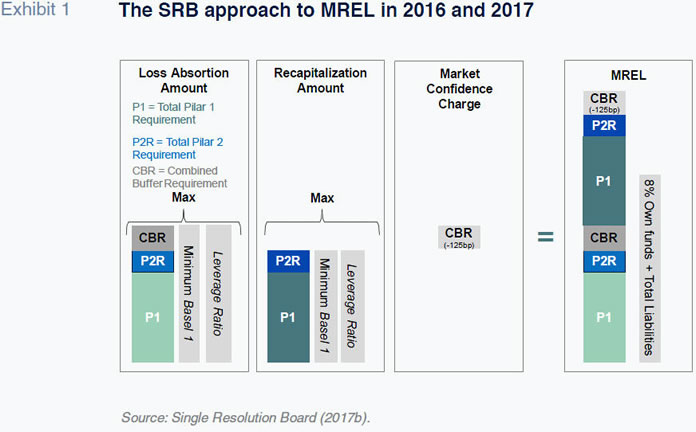

On December 20th, 2017, the European Single Resolution Board (Single Resolution Board, 2017a) published a new guide, fine-tuning that of 2016, on MREL, which includes the basis for its calculation and breaks down its two basic components: a default loss absorbing amount (LAA) and a recapitalisation amount (RCA).

Although the first attempt at defining the base for calculating the MREL requirement considered the use of total assets, the definitive version has opted for risk-weighted assets (RWA), in line with the instrument defined by the FSB for systemic entities (G-SIIs), TLAC. This ensures greater consistency for the entities that must meet and report the two requirements.

In order to calculate the minimum loss absorbing amount, entities must use the highest of the following three measures:

- The sum of the pillar 1 and pillar 2 regulatory capital requirements and the combined buffer requirement (on a fully-loaded basis).

- The Basel 1 floor requirement;

- In a new development, this formula of maximums contemplates the leverage ratio, although this will not take eff until it is a compulsory ratio in the eurozone.

The second core MREL component defined by the SRB is the so-called recapitalisation amount, which reflects the capital needed to meet ongoing prudential requirements after resolution and is the maximum of:

-

The sum of pillar 1 and pillar 2 capital requirements;

-

The Basel 1 floor requirement;

-

And the leverage ratio (again, new).

In addition to the two basic components, MREL contemplates the need to ensure market confidence post-resolution, to which it adds a new ‘market confidence charge’ (MCC), which consists of the combined capital buffer requirement less 125bp.

Notwithstanding these three components which add together to make up MREL, and which we will quantify later, it is important to clarify certain specific aspects.

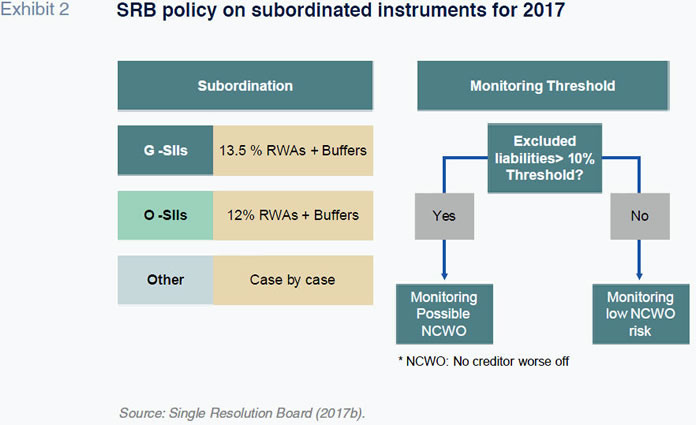

The first relates to the subordination benchmarks. Specifically, to comply with MREL, banks will have to tap the market to issue a minimum percentage of bail- inable instruments depending on their systemic importance. Specifically, for global systemically important institutions (G-SIIs), the subordination benchmark is 13.5% of their risk-weighted assets plus the combined buffer ratio. For other systemically important institutions (O-SIIs), the subordination benchmark is 12% plus the CBR. And for other banks, this requirement will be analysed on a case by case basis.

Elsewhere, the ongoing MREL debate is also taking into consideration the resolution strategies deemed reasonable for one entity versus another and their implications for MREL requirements. Specifically, for entities not considered systemically important, for which it would be logical to believe that the resolution strategy would consist of a trade sale, it is reasonable to assume that, after the resolution losses are absorbed, the bank would be recapitalised by the buyer, as indeed was the case of Banco Popular, which was bought and recapitalised by Banco Santander. If this is the key assumption for these kinds of entities, it does not make sense to require them to maintain the full MREL recapitalisation amount.

In this respect, the most recent report by the EBA on the updated impact of MREL [1] assumes that the resolution funding requirement for entities not categorised as systemically important would be 50% of the theoretically defined amount based on the understanding that these banks would be resolved via trade sales for the most part, such that they would not need to hold bail-inable liabilities in respect of the recapitalisation amount as this process would presumably be handled by the buyer. In this paper, in calculating the bail-inable liability funding needs by entity, we also make this assumption on the understanding that these banks cannot be expected to meet the same requirement as their systemically important counterparts.

In addition, the guide published by the SRB carves out the following liabilities as eligible for MREL calculation: long-term deposits (more than one year) not covered by the Deposit Guarantee Fund and those that have a redemption clause below one year or for which there is no sufficient evidence that they cannot be withdrawn. Elsewhere, it reaffirms the exclusion of structured notes and instruments issued by entities outside of the EU.

Spanish banks, state of play vis-á-vis MREL

Based on the above assessment, we can say that the definitive version of the SRB’s MREL is not quite ready and that each entity’s requirement could well vary as a result of its ‘resolvability’ and/or systemic importance.

Nevertheless, based on the three MREL components defined to date, we have estimated the requirement for each of the Spanish banks subject to direct supervision by the SSM.

The estimates were made on the basis of the assets of each of the 14 most significant banks (which represent over 85% of the Spanish banking sector’s assets) at year-end 2016, as gleaned from their annual financial statements for that year, this being the most recent information available at this time.

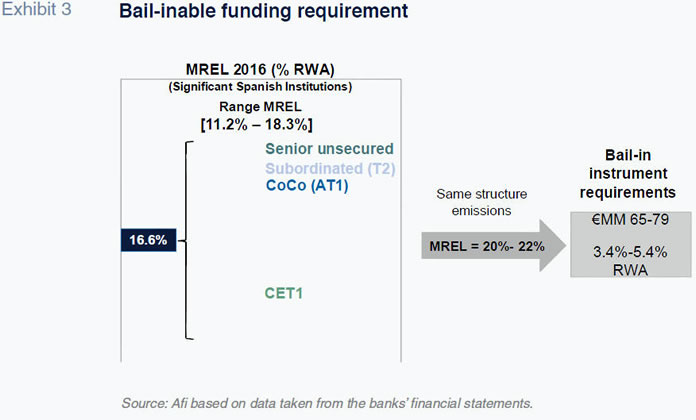

The first source of heterogeneity in the various entities’ MREL requirement stems from the components tied to the pillar 2 capital requirement and capital buffer requirement, both of which are defined specifically for each entity. Factoring in this link to variable pillar 2 and capital buffer requirements, we estimate that the loss absorption amount will range between 10% and 12%, that the recapitalisation amount will range between 8% and 10%, and, lastly, that the market confidence charge will come in at between 1.5% and 2.5%. The sum of these three components will translate, on average for the significant entities, into a requirement for bail-inable instruments of between 20% and 22% of their total RWAs.

As shown in Exhibit 3, at December 31

st, 2016, these 14 significant entities on aggregate presented a volume of bail-inable liabilities equivalent to 16.6% of their RWAs (with a range of 11.2% – 18.3%),

i.e., between 3.4 and 5.4 percentage points below our estimated average requirement.

Of the 14 banks’ bail-inable liabilities, 75% is accounted for by common equity tier 1 capital (CET 1), 6% by convertible bonds, 5% by subordinated bonds and the remaining 14% by senior notes.

Starting from the amount of bail-inable liabilities that each entity already has, and assuming that they all have to reach the range of 20% to 22% estimated as the average benchmark for the sector as a whole, the funding requirement for meeting the MREL requirement would amount to between 65 and 79 billion euros, based on December 2016 data. Next, we analyse how the entities have already made significant progress in 2017 towards closing the gap between the bail-inable liabilities they hold and those they will be required to have when MREL becomes binding.

Banks’ response to MREL

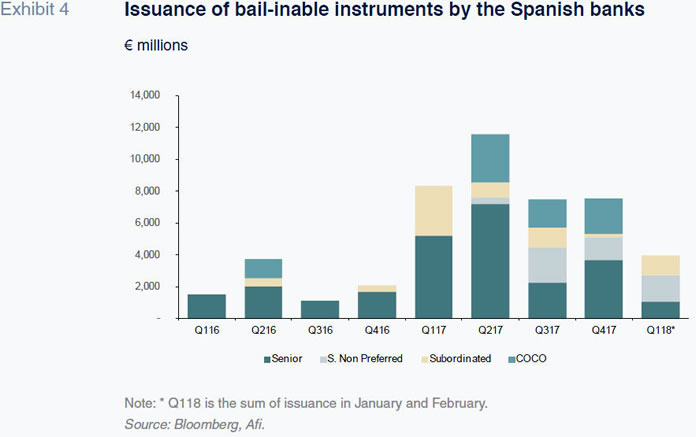

As shown in Exhibit 4, in 2017, Spanish banks stepped up their issuance of liabilities deemed eligible for the MREL ratio, issuing almost 35 billion euros in total, which is more than three times the amount issued in 2016.

As for the types of instruments issued, it is worth noting that Spanish legislation (specifically Royal Decree 11/2017, of June 23rd, 2017, on urgent financial measures) has regulated the possibility of issuing a new instrument that would compute for MREL purposes, namely senior non-preferred instruments.

This legal backing for a new instrument clearly designed to facilitate compliance with the MREL requirement has prompted intense issuance of non-preferred senior instruments, particularly by the larger Spanish banks: issuance of this new instrument totalled 4 billion euros in 2017, a trend continuing in 2018, with a further 1.6 billion euros issued by mid-February 2018. It is foreseeable that this will be one of the core instruments around which the banks articulate their funding plans.

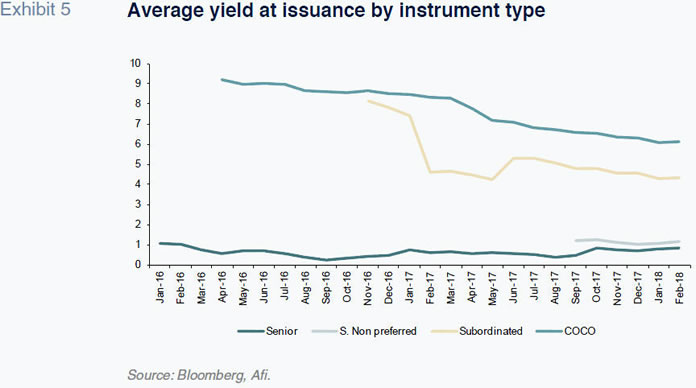

Elsewhere, is it worth analysing the terms on which the Spanish banks have tapped the market. Notably, the terms of issuance, specifically the rate of interest (yield) has trended considerably lower since 2016, evidencing improved market confidence in the banking sector in general and Spanish banks in particular.

Exhibit 5 illustrates how all throughout 2017, market terms were far more favourable than in 2016, marked by a substantial improvement in the instruments that qualify as capital, such as contingent convertible bonds (COCOs) and subordinated bonds.

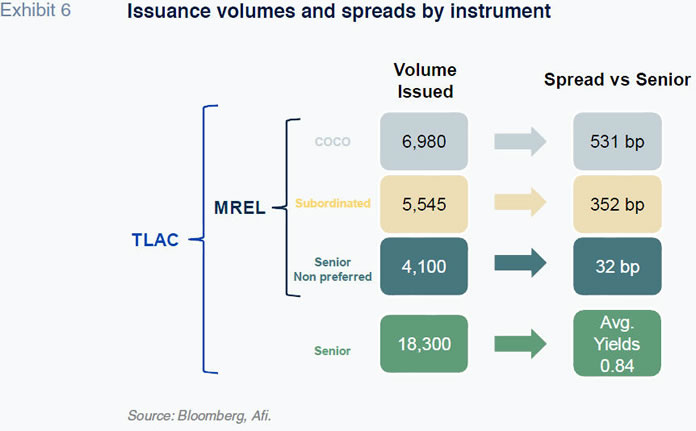

By way of summarising this widespread improvement in issuance terms, Exhibit 6 depicts issuance volumes by instrument type alongside the average issuance yields in 2017. Note in respect of non-preferred senior instruments, by virtue of qualifying as bail- inable instruments, the market priced them at a spread to traditional senior paper of around 30bp.

The improvement in financing terms has facilitated the banks’ task of issuing subordinated instruments in order to meet this new regulatory requirement. And as long as the rate curve remains at an all-time low, it is likely that banks will continue to issue bail- inable instruments in this vein.

Conclusions

In the wake of the new prudential requirements in the capital adequacy arena, the regulations addressing instruments eligible for resolution strategies (MREL) are in the process of being finalised.

The definition of MREL components (loss absorption amount, recapitalisation amount and market confidence charge) was substantially narrowed down at the end of 2017, notwithstanding the adjustments that may ultimately be made for each entity. Based on the newly defined general requirements, we have estimated Spanish banks’ possible bail-inable instrument funding requirement and analysed the issuance activity of 2017 in a bid to meet the expected new requirements.

By our estimates, as of year-end 2016, the significant Spanish banks need to issue between 65 and 79 billion euros to meet the MREL requirement once it becomes binding, which will not be earlier than four years from when each entity is notified of its requirement. In 2017 alone, banks issued a volume equivalent to 25% of that figure, with the issuance of senior non-preferred notes standing out, this instrument having been specifically regulated in Spain, emulating the example set in other countries, as particularly suitable for MREL compliance purposes.

Not only has this issuance effort been intense volume-wise, it is also worth highlighting the fact that investor appetite for these instruments has translated into very favourable issuance terms (interest rates) which in all likelihood will continue to prevail this year, as is foreshadowed by issuance activity during the first six weeks of 2018.

Notes

EBA (December 20th, 2017), Quantitative update of the EBA MREL report (December 2016 data).

References

EUROPEAN BANKING AUTHORITY (2016), Quantitative update of the EBA MREL report.

ROJAS, F.; SÁNCHEZ E., and F. J. VALERO (2018), Basel III reforms and implications for European and Spanish banks.

SINGLE RESOLUTION BOARD (2017a), MREL: Approach taken in 2016 and nest steps.

_ (2017b), Minimum Requiement for Own Funds and Eligible Liabilities (MREL), SRB Policy for 2017 and Next Steps.

Ángel Berges, Alfonso Pelayo and Fernando Rojas. A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.