European and Spanish banks: Dominating the primary debt markets

Favourable market conditions and the need for compliance with regulatory capital requirements have driven a surge in European, and in particular Spanish, banks’ primary debt markets issuance. Even as banks continue to take advantage of newer, less costly MREL-eligible instruments, the estimated shortfall to meeting average MREL levels means European banks will continue to be significant issuers in fixed-income markets over the coming years.

Abstract: Financial markets’ propitious start to the year has led to the intensification of issuance in the European and Spanish primary fixed-income markets. Issuers’ swift reactions to benign market conditions, coupled with strong investor take-up in light of ultra-low rates, has been even more apparent in the banking sector, which has been taking advantage of the momentum to address regulatory pressure deriving from the upcoming deadline for compliance with the resolution directive, specifically, the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL).Within this context, two trends have emerged. On the one hand, having maxed out the allowances for certain instruments (convertibles bonds, CoCos and subordinated debt) that dominated issuance volumes up until 2017, banks are switching to issuance of lower-cost liabilities, such as senior non-preferred debt, which qualifies for MREL purposes. In parallel, there has been a ‘democratisation’ trend in issuance, with smaller-sized entities tapping the markets more than before. According to our estimates, European and Spanish banks will need to raise another 250 billion and 50 billion euros of eligible instruments, respectively, to comply with the MREL deadline set for 2024. Thus, we anticipate banks to remain dominant players in the primary fixed-income markets for the coming years.

[1]

Introduction

The propitious start to the year in the financial markets has prompted intensification of issuance in the European and in Spanish fixed-income markets. That swift reaction to benign market conditions, coupled with strong investor take-up in light of ultra-low rates, has been even more apparent in the banking sector, in Europe and in Spain. The financial sector has been taking advantage of the momentum to address regulatory pressure deriving from the upcoming deadline for complying with the resolution directive, i.e., the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL).

It is worth highlighting two trends attributable to the recent wave of fixed-income issuance by Spanish banks. On the one hand, having issued high volumes of the more subordinated instruments in recent years (CoCos and subordinated bonds), banks are now switching to lower-cost liabilities, such as senior non-preferred debt, which has the added advantage of computing for MREL purposes. On the other hand, the number of issuers has increased considerably and the presence of smaller-sized entities is on the rise.

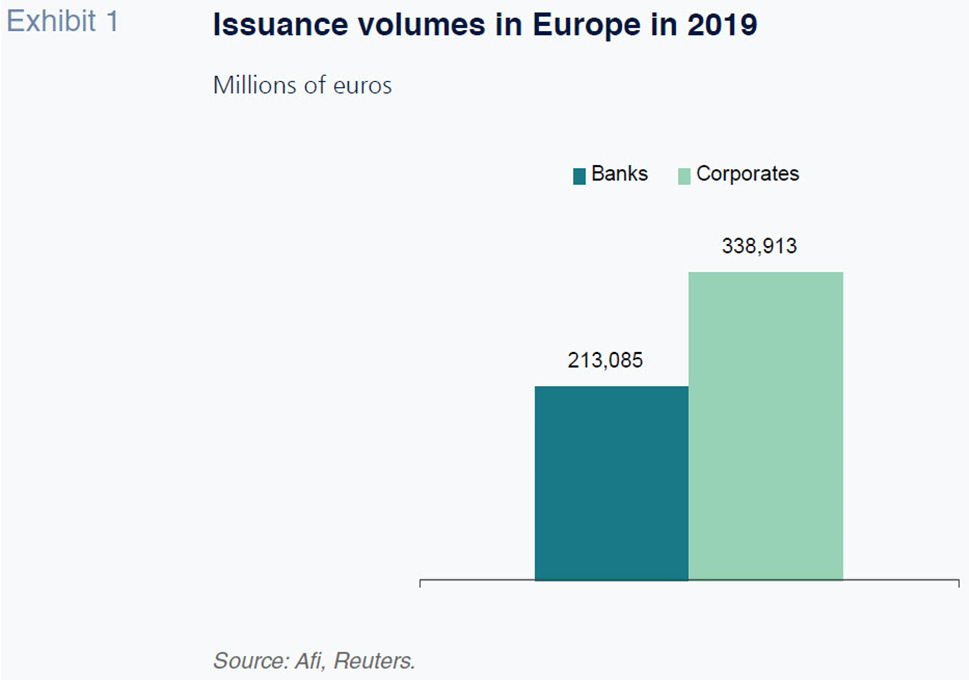

It should not come as a surprise, therefore, that in Spain, to a greater extent even than in Europe, the banking sector has dominated the market of private sector issuers in the early weeks of the year, significantly outweighing issuance across the rest of the corporate universe.

Issuance volumes and yields (‘correlation’ between yields and volumes)

Borrowing conditions have improved considerably in recent months. Two of the key sources of risk weighing on the markets in 2019 dissipated towards the end of the year with: (i) a rapprochement between the US and China, which materialised in phase one of a trade agreement between the two economic powers; and, (ii) definitive approval of an ‘orderly Brexit’.

All of that encouraged issuers to the tap the primary debt markets during the early weeks of the year. Issuance cooled off a little, however, during the second half of January due to fears over the Coronavirus outbreak in China.

Although the banks typically concentrate their issuance volumes in the early part of the year, that effort has clearly been more intense this year. The more than 6 billion euros of debt issued by Spanish banks in January 2020 is triple the amount issued in January 2019. Moreover, Spanish banks issued more debt than all the other private sectors together and accounted for nearly 18% of all debt issued by European banks that month.

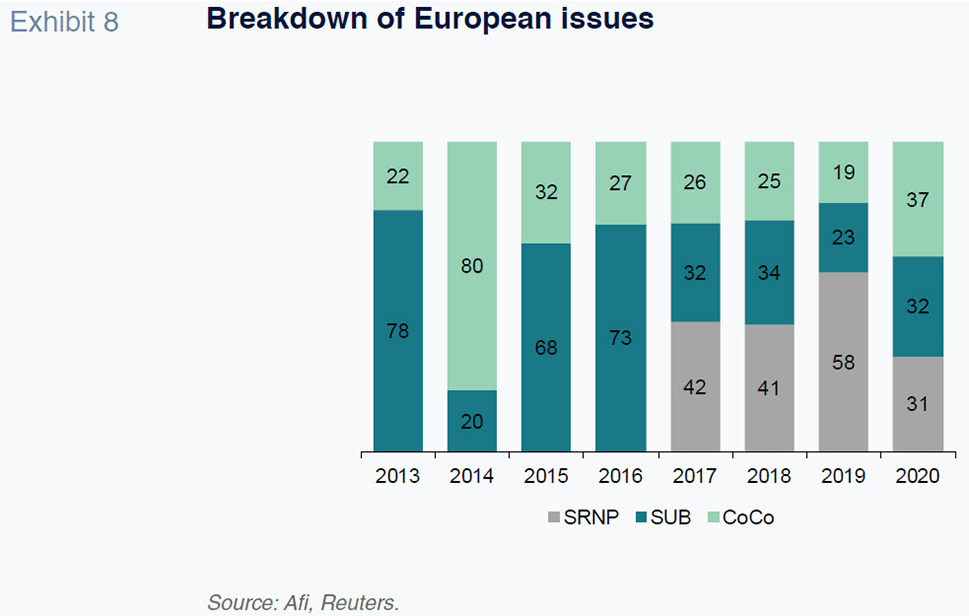

The difference in yields among the various instruments reflects subordination in terms of loss absorption: CoCos being the most expensive, followed by subordinated debt, with senior non-preferred debt in third place – this being the newest instrument to be regulated in Spain. Senior non-preferred debt was made eligible for MREL purposes in Spain in 2017, offering the banks a much more attractively priced alternative to CoCos and subordinated debt, which explains its high issue volumes as of that same year.

Nevertheless, the significant improvement in issuance terms in recent months has made these instruments even more attractive, both for new issuers and for refinancing prior ‘expensive’ issues by exercising the call options they all feature. That is the main factor behind the surge in CoCo issuance observed at the start of 2020, as illustrated in Exhibit 8.

Exercising the call option to refinance on more favourable terms is a logical financial decision, as we have outlined in a prior paper (Berges, Pelayo and Pino, 2019), and is not related to higher or lower capital levels or market signals. The banks simply exercise the call option in the event that it is cheaper to issue new CoCo. Otherwise, the call option is not exercised.

Beyond these decisions, driven by purely financial and market considerations, banks’ issuance plans are being heavily shaped by the implementation timeline and readiness for MREL compliance against the backdrop of the new bank resolution regulations.

MREL: Requirements and readiness

The Minimum Requirement for own funds and Eligible Liabilities (MREL) constitutes an additional regulatory requirement (in addition to the capital requirements) for the banks. It is a preventative measure designed to prepare an entity for a hypothetical declaration by the supervisor that the entity is ‘failing or likely to fail’, thus triggering resolution.

The idea, therefore, is to create a buffer such that the entities have the capacity to absorb enough losses and subsequently recapitalise.

[2] All of which using their own funds and liabilities (bail-in), with the aim of minimising the need to resort to public aid (bail-out), as happened during the last crisis.

The MREL is determined at the individual level (entity by entity) by the Single Resolution Board (SRB) for significant entities, with the national competent authorities determining the thresholds for the less significant entities. The precise level depends on the entity’s risk profile and other aspects that could impede resolution (structural complexity, interconnections, critical functions, etc.), in addition to the chosen resolution strategy.

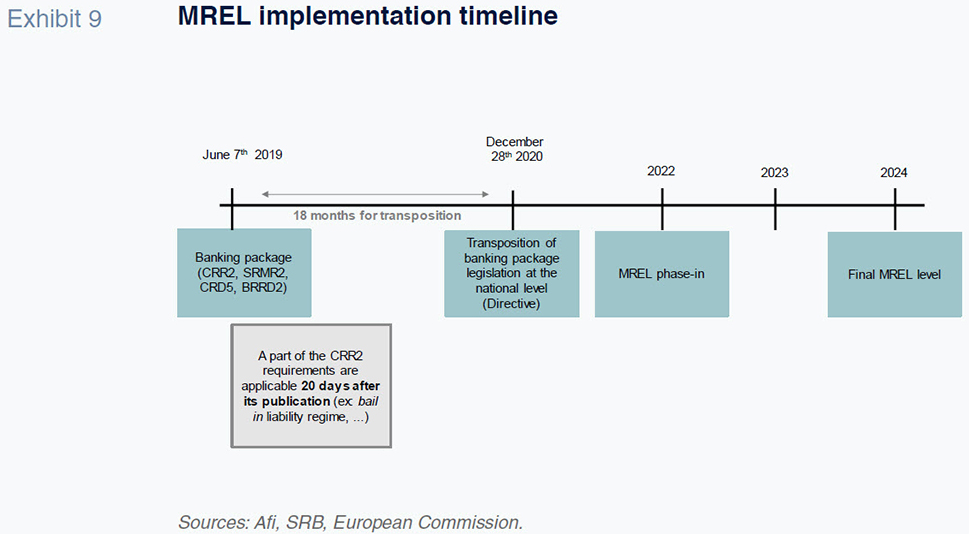

As was the case with the new capital requirements (Basel III), the MREL will be phased in. The phase-in is important as the MREL will require a major effort in terms of the volume of issuance of eligible instruments, which the market will have to digest gradually.

As shown in Exhibit 9, January 1

st, 2024, is the deadline for MREL compliance by the banks, in keeping with the recently published BRRD II, although they have to comply with a binding interim requirement by 2022.

The smaller-sized banks are being allowed a certain amount of flexibility: the authorities could extend the deadline for smaller financial institutions beyond 2024, depending on an entity’s situation, issuance capacity, instrument renewal or financing structure, particularly entities with a predominance of deposits and CET1 capital, i.e., limited access to the markets.

In short, pressing deadlines are prompting banks to shift their issuance strategies to focus on instruments that compute for MREL purposes, buoyed by low rates and investor appetite for the attractive coupons those instruments offer them.

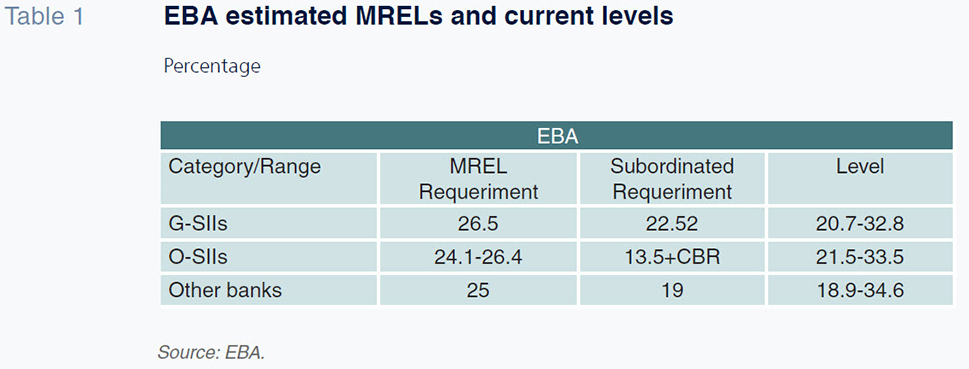

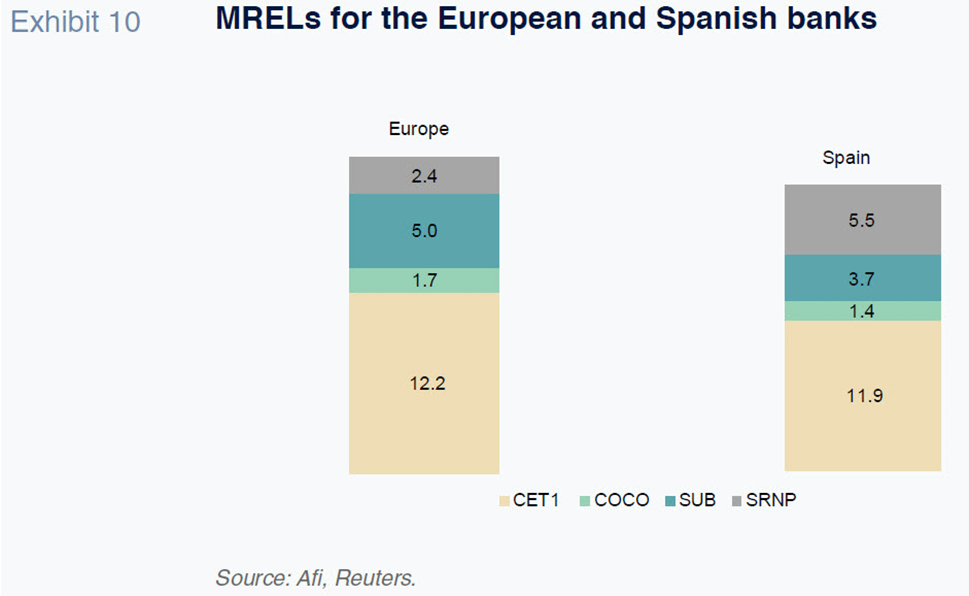

Given the heterogeneity of business models and diversity of internal model calibration, among other factors, as noted before, the MREL will be ‘tailored’ for each entity. Judging by the MREL levels already set for the banks by the SRB and analysing a sample of 30 significant banks in Europe, the MREL calibrated for the European banks is around 26% of their risk-weighted assets on average, compared to 23% in Spain. By way of comparison, Table 1 illustrates the levels reported by the EBA in its recently published EBA Quantitative Report on MREL for the entire sample under the umbrella of the SRB. The EBA estimates the average requirements by three categories: the global systemically important institutions (G-SIIs), other systemically important institutions (O-SIIs) and, other entities (Other). The levels determined are: i) an average of 26.5% for the G-SIIs; ii) between 24.1% and 26.4% for the O-SIIs; and iii) approximately 25% for those categorized as Other.

Beyond the business model considerations or lower complexity vis-à-vis resolution, the lower MREL determined for the Spanish banks relative to their European counterparts may have to do with different risk-weighted asset (RWA) densities. Some of the major European banks are well known for presenting relatively low RWA densities as a result of application of their internal risk models, currently the subject of intense market scrutiny. In fact, the initial attempts at calibrating the MREL referred to total assets, which is a far more transparent metric than RWA. However, the advisability of aligning the MREL with the G-SIIs’ total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) requirements meant that the MREL was ultimately defined as a percentage of RWAs rather than total assets. It may well be that by way of ‘gesture’, the banks presenting less dense RWAs on account of application of their internal models have been asked for a higher MREL.

Regardless, what is important is to analyse the current distance to compliance with those requirements. Exhibit 10 shows that the European banks currently report an MREL of around 23%,

i.e., roughly 3 percentage points below the average threshold. In Spain, the current average MREL is around 19%. The comparison between the current situation (as of year-end 2019 for some of the banks and June 2019 for others) and the estimated average threshold suggests that European banks will have to issue an additional 250 billion euros of eligible instruments, and the Spanish banks, around 50 billion euros. That issuance requirement could rise a little as a result of implementation of the finalization of Basel III (or Basel IV), particularly the introduction of the ‘output floor’ for the RWAs calculated using internal models, which will have a far bigger impact on banks (mainly on the German and French banks) whose RWAs benefit more from those models.

Turning back to the EBA’s analysis, the estimated current situation for each of the three categories is as follows: between 20.7% and 32.8% for the G-SIIs; between 21.5% and 33.5% for the O-SIIs; and between 18.9% and 34.6% for the rest. On aggregate, according to the EBA, the European banks will need to raise around 180 billion euros of eligible funding. The difference between our calculations and those of the EBA may be attributable to:

- Different sample space used in the calculations.

- Our estimates of the MREL currently presented by the banks consider instruments to be eligible down to senior non-preferred debt, i.e., excluding senior preferred debt and corporate term deposits of more than one year.

- We assumed that the CET1 capital [3] used to meet the MREL as a percentage of RWA is not included in the CBR, [4] in keeping with the new banking package. [5]

- As the SRB establishes in the new 2020 policy (on request), the new requirement must comply in parallel, with MREL over the leverage ratio (LRE) in order to complement the MREL over RWAs. As a function of the levels presented by the banks over total exposure (total assets plus off-balance sheet exposures), we have estimated a percentage increase for some of the banks with lower LREs.

Conclusions

European and in particular Spanish banks have taken advantage of the favourable market climate towards the end of 2019 and beginning of 2020 to accelerate their fixed-income issuance. So much so that the the volumes issued by the Spanish banks so far in 2020 exceed the amount issued by the rest of the corporates combined, such that the banks are clearly dominating the primary markets.

Within the issuance volumes, we are witnessing a clear-cut shift towards MREL-eligible instruments, which now consist of more options and on which spreads have narrowed considerably during the past year. That has enabled issuers to refinance their more expensive issues (CoCo) by duly exercising their call options.

In addition to the favourable market context, the intense pace of issuance activity by the Spanish and European banks is being driven by the proximity of the MREL deadlines. We estimate that the Spanish banks will have to issue another 50 billion euros of eligible instruments in order to comply, with the equivalent requirement for European banks as a whole estimated at 250 billion euros.

Notes

This article was completed in the first week of March. At that time, the effects of the current crisis caused by COVID-19 and the decisions made by the different European institutions and governments to counteract them were unknown. However, these decisions do not invalidate the analysis presented below.

This will depend on the resolution strategy, as both the SRB and the recently published BRRD II distinguish between the following situations: full bail-in, sale of business, bridge bank, asset management company. The regulations permit adjustments in the MREL –upwards or downwards– as a function of the chosen strategy.

CET1: Common equity tier 1.

CBR: Capital buffer requirement.

Also contemplated in the consultation on MREL Policy 2020, published by the SRB last February.

References

BERGES, A., PELAYO, A. and PINO, J. (2019). CoCos (AT1) versus capital (CET 1) at Spanish and European Banks. Spanish and International Economic & Financial Outlook.

BERGES, A., PELAYO, A. and ROJAS, F. (2019). Spanish banks ahead of MREL: Estimating projected issuance for compliance. Spanish and International Economic & Financial Outlook.

EUROPEAN BANKING AUTHORITY. (2020). EBA Quantitative MREL Report. EBA/REP/2020/07.

MARTÍNEZ GUERRA, M. (2019). The new European Bank Resolution Directive in the face of MREL adaptation. Spanish and International Economic & Financial Outlook.

SINGLE RESOLUTION BOARD. (2020). Minimum Requirement for Own Funds and Eligible Liabilities (MREL). SRB Policy under the Banking Package.

Desirée Galán, Javier Pino and Fernando Rojas.

A.F.I. - Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.