The Spanish financial system in the new political era

Spain´s financial stability remains intact, underpinned by the ongoing economic recovery. However, concerns over political uncertainty could still place a brake on investment and financing flows, at least over the short to medium-term horizon.

Abstract: Spain´s economic recovery remains on track, but the lack of a majority government following recent elections is giving way to a delicate political balancing act. There are no grounds for concern over the country’s financial stability. Nevertheless, prolonged political uncertainty could slow investment and funding flows. The reforms, restructuring, write-downs and recapitalisations that the Spanish financial sector has undergone over the last four years ensure its foundation. A gradual return to positive year-on-year credit growth is expected between 2016 and 2019. The default rate is projected to drop from 8% in 2016 to around 3% by 2019. The major challenges the sector will need to confront over the next four years will include reactivating lending, raising profitability, privatising nationalised institutions and adapting to increased regulatory pressure. Moreover, Spanish banks must make changes to their business models, adopting a risk-management structure more focused on SMEs and devoting more attention to technological changes in retail services.

Financial stability in a context of political uncertainty

The current transition between two legislative periods is paradoxical. The past four years have been characterised by severe crisis followed by an incipient economic recovery, under a government that guaranteed stability through its absolute majority. The next four years should see the economic recovery gain traction, but have started off with considerable political uncertainty. At present, it is difficult to predict the new political equilibrium, as parties jockey to form coalitions and it is by no means clear that a new round of elections would produce a stable result.

This is clearly an unprecedented scenario for Spain’s democracy, and one that all observers, analysts and investors are watching closely. Uncertainties surrounding the legislative transition in Spain have not gone unnoticed by rating agencies. The day after the elections, December 21st, 2015, Moody’s issued a note saying that the “inconclusive parliamentary election has increased political uncertainty and raised doubts about the future government’s ability and willingness to continue with structural reforms and fiscal consolidation, a credit negative. Forming a new government is likely to be difficult and a failure to do so would lead to a new round of elections and a prolonged phase of political uncertainty.” As Moody’s points out, this also means that “notwithstanding significant progress made, recent years have also seen a sequence of missed fiscal targets, the future likelihood of which will only be increased by an uncertain electoral result.” In any event, for the moment, Moody’s considers that “the positive outlook on Spain’s Baa2 government bond rating balances the country’s improving economic and credit fundamentals and reform progress against the uncertainty over future reform impetus.”

In a similar vein, on the same day, Fitch stated that, “the inconclusive outcome of Spain’s general election increases the related risks of prolonged political uncertainty, and potentially a looser fiscal policy stance and/or a reversal of structural reforms.” Fitch also said that “the recent strong cyclical economic recovery has offset some risks posed by the stalling of fiscal consolidation [...]. Combined with very low interest rates, this has helped reduce budget deficits [...]. But Spain’s fiscal adjustment is still incomplete.” Fitch expects that “in the short run, political uncertainty is likely to have limited impact on fiscal policy as the 2016 budget was approved before the elections. We maintain our baseline assumption that any new government will keep public debt/GDP declining in the latter half of the decade [...]. But an extended period of political uncertainty and the possibility of a partial reversal of reform and consolidation measures could damage economic confidence and reverse the current benign macro-fiscal dynamics.”

How could this situation affect the Spanish financial system? After years of intensive restructuring and recapitalisation, the Spanish banking sector has emerged from the crisis stronger and more resilient. However, there are still major outstanding challenges, such as operational rebalancing (i.e., increasing lending and raising profitability) and privatisation, which must be faced in an environment of increased regulatory pressure, the enduring impacts of the crisis on the strength of credit demand and political uncertainty.

In this context, the following article analyses the implications of the transition between the two legislative periods for the Spanish financial system, and what the years ahead are likely to hold. The exercise is constrained by uncertainty surrounding current forecasts. The article will therefore project financial aggregates for 2016 under a “central scenario” that assumes no political equilibria in the short and medium-term and the resulting implicit cost of this for the economy. It also considers long-term forecasts for 2019, based on a scenario of potential equilibrium of the Spanish economy in a baseline scenario of reasonable political stability. In the case of 2016, the effect of external factors with significant potential impact on the Spanish financial system is also considered, such as instability in China and other emerging markets.

Key issues affecting the Spanish financial sector

The changes the Spanish financial system − and the banking sector in particular − has experienced in recent years have been some of the most intense in its recent history. The effects of the crisis, and the process of “orderly restructuring” begun by the FROB in 2009, have been extensively documented in Spanish Economic and Financial Outlook, but in this instance, we are referring specifically to the processes under way since 2012 and which may, to some extent, continue until 2019.

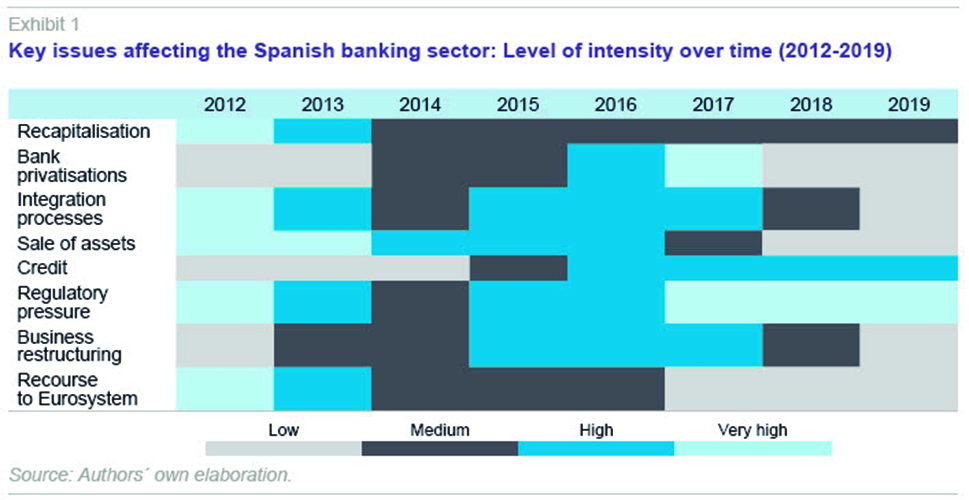

As Exhibit 1 shows, it was in 2012 that the Spanish banking system really began to focus on capital requirements, after several years in which efforts had been dedicated primarily to restructuring. Amid severe pressure in European sovereign debt markets, this was the year in which Spain had to turn to the EU for help to ensure the solvency of its banking sector. This meant signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) that led to the implementation of a series of corrective, preventive and proactive measures, which were supervised and monitored until the end of 2015. However, recapitalisation remains one of the long-term goals due to the presence of worldwide regulatory and market pressure to raise banks’ solvency.

In a number of cases, the recapitalisation process implied the FROB’s entry into financial institutions’ capital. Various measures were taken in 2014 and 2015 − including shares issues by financial institutions − with a view to partial or total privatisation. However, as the MoU indicated, this process may take until the end of 2017. The political uncertainty with which 2016 began leaves much of the capacity for action down to institutions’ own initiative. In this regard, as will be discussed below, the restructuring of the Spanish banking sector is expected to continue, and will include further consolidation for at least the next two years.

Another important issue − partly in response to the demands of the crisis and partly required under the MoU − is the sale of assets by the banks. For the first time in over 70 years, Spanish financial institutions have reduced their assets. This downsizing is linked to the restructuring process, which at the end of the day, reflects the necessary adjustment to the reality of lower demand in the wake of the financial crisis. Selling assets has allowed many financial institutions to obtain resources with which to bolster their solvency, pay down their debt, or offset impairment losses on other investments.

Concerns over the recovery of credit flows have been the main focus of attention. Although credit has been contracting over the last four years, new credit is beginning to grow significantly, with positive changes in balances expected in 2016.

As regards regulatory pressure, the processes of orderly resolution in Spain, under European supervision, have led to a significant increase in regulatory requirements and in 2019, the provisions of the Basel III agenda will shape the intensity of regulation. Aspects not previously considered − and subject to much debate − such as penalising the holding of public debt securities on banks´ balance sheets, may be incorporated.

One increasingly prominent issue, which will also be dealt with specifically below, is the role of Spanish banks in the corporate restructuring processes. In addition to the close links between banks and businesses in Spain, through shareholdings and finance, there are recent regulatory provisions that have fostered the process of resolution of corporate debt.

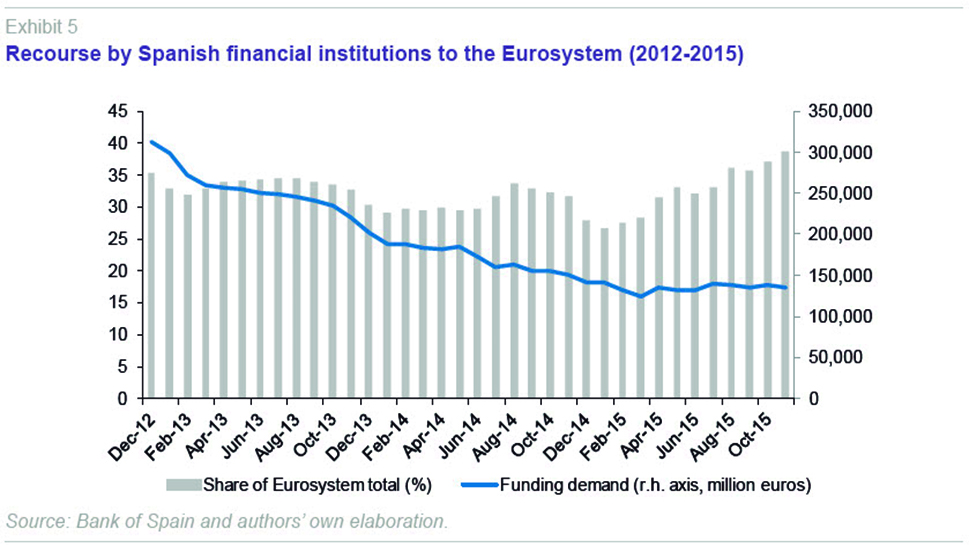

Finally, one key feature of Spanish financial institutions’ activity in recent years has been their dependence on Eurosystem liquidity. As will be discussed below, although this dependence has decreased in absolute terms, it remains significant relative to the rest of Europe.

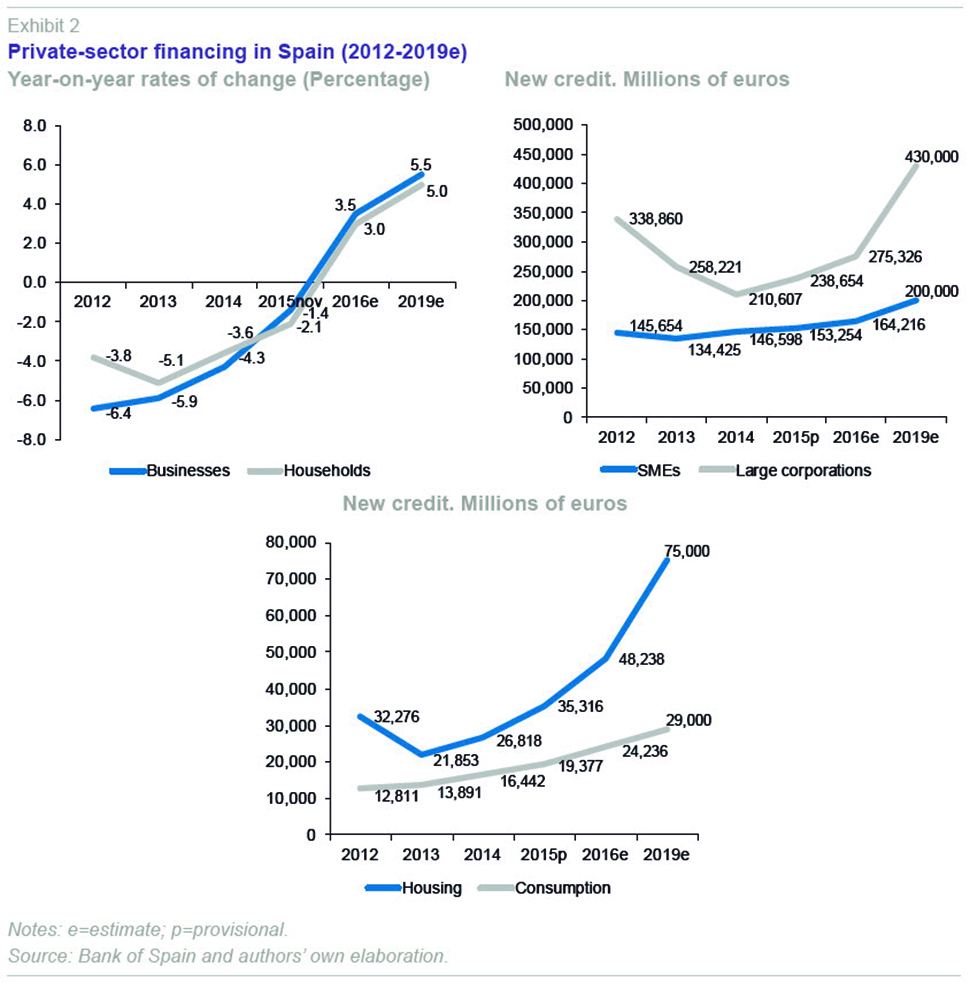

In terms of the quantitative analysis, taking credit as the starting point, private sector finance in Spain registered negative year-on-year rates of change up until November 2015 (the most recent data available), as is shown in Exhibit 2. However, in 2016, these rates are expected to be 3.5% for businesses and 3% for households, with rates of 5.5% and 5%, respectively, anticipated in the longer-term.

In any event, as Exhibit 2 also shows, the number of new credit transactions has been rising significantly since mid-2014, for SMEs and large corporations. In the case of large corporations, debt repayments still seem to be playing a major role, although corporations are expected to account for a significantly larger share of new borrowing in 2019.

As regards new household credit, consumer credit has been growing strongly since 2012, and housing finance has recently started picking up as well. The latter is set to grow considerably in the next few years, although well below pre-crisis rates for now, in line with a more sustainable growth of the residential property sector.

Overall, debt repayments continued to outweigh new transactions in 2015. Although positive rates of change are expected in 2016, they will fall somewhat short of initial estimates as a result of political uncertainty. Much of the sector has shown its willingness to undertake corporate transactions, while a further substantial share is still waiting for its privatisation plans to reach completion. The good news is that the Spanish banking system has made better progress on restructuring than most of its European peers and has enhanced transparency over the quality of its assets to an extent that is unparalleled elsewhere in Europe.

Regulatory pressure is another factor that will have a negative impact on credit. However, this is largely foreseen, and therefore discounted in the forecasts. On this point, is worth mentioning that on December 28th, the Bank of Spain set the capital buffers for systemically important institutions and the countercyclical buffer for 2016. The latter was set at 0%. The buffer for systemically important institutions was set in the range of 0 to 0.25%,depending precisely on how “systemically important” each institution is deemed to be.

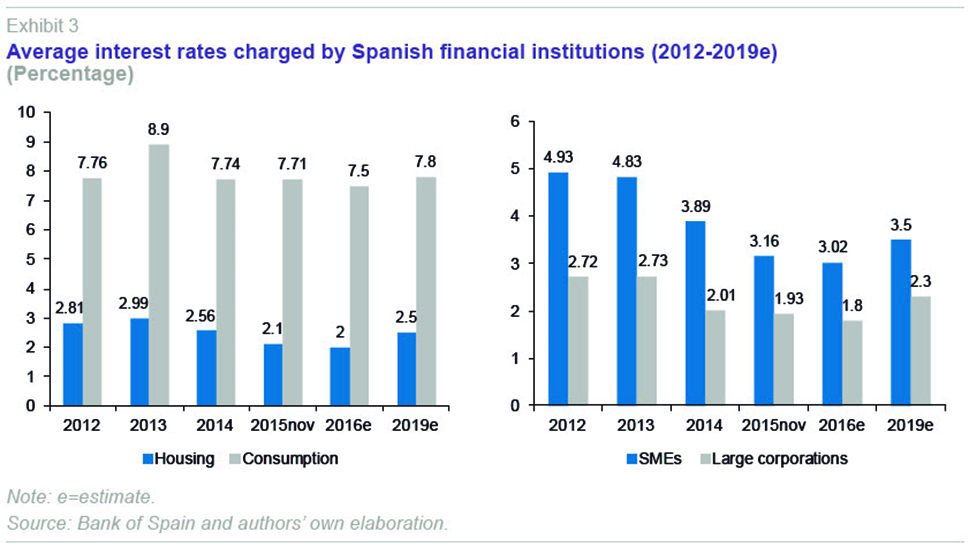

One factor favouring credit growth, however, is the trend in interest rates (Exhibit 3). Since 2013, there has been a substantial reduction in the average rates charged by Spanish financial institutions. Thus, for example, the average rate on consumer credit was 8.9% in 2013, compared with 7.7% at the end of 2015. In the case of housing loans, the average rate fell from 2.9% to 2.1%. In the corporate segment, the average rate for SMEs dropped from 4.83% to 3.16% over the same period, while the rate for large corporations dropped from 2.73% to 1.93%. This downward trend has been continuing for some time, but it may extend into 2016 and reverse somewhat thereafter. Although the ECB is not expected to tighten monetary policy in the medium term, it is possible that the downward trend in rates may bottom out as inflation picks up as expected in 2016.

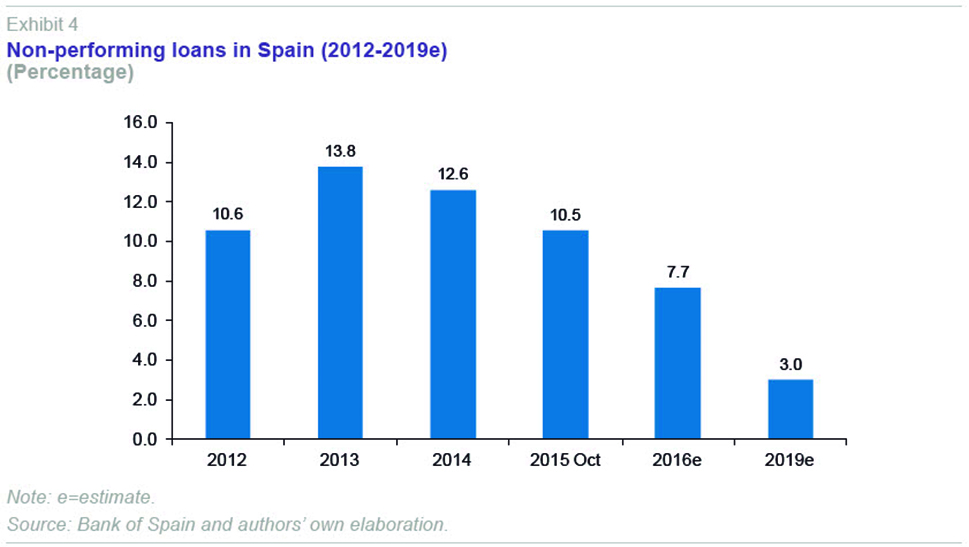

The negative impact of the crisis is also visible in the default rate. The ratio of NPLs to total loans (Exhibit 4) reached 13.8% in 2013 and has been gradually declining since, dropping to 10.5% in October 2015. As the percentage of doubtful loans declines − bearing in mind the likely increase in total credit − it is possible that the ratio will drop to below 8% in 2016 and to around 3% in 2019.

One final important issue concerning credit is the funding available to Spanish banks. The European Central Bank’s stimulus has become essential to maintaining financing flows, and it was particularly significant when sovereign risk tensions peaked in 2012. As Exhibit 5 shows, the share of Eurosystem funding has fallen drastically since 2013, dropping from funding demand of over 300 billion euros in 2012 to demand of around 130 billion euros in late 2015. However, it is worth noting that the Spanish banking sector is still absorbing over 35% of the total of this type of funding.

Structural changes

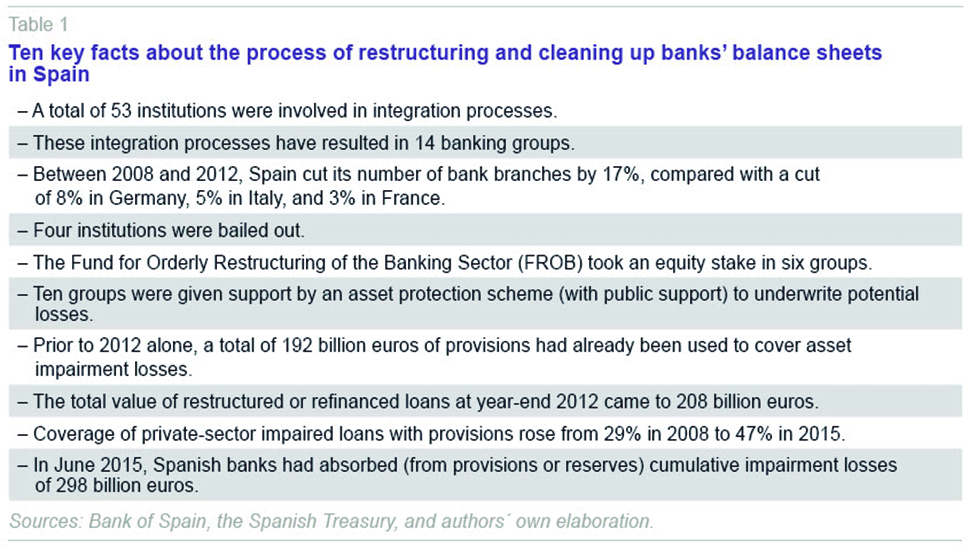

Among the recent developments within the Spanish banking sector, the restructuring process has drawn significant attention. As a consequence of the intensity of the process, as shown in Table 1, there was a sharp reduction in the number of competitors, associated with a significant allocation of resources to restructure balance sheets, largely supplied by financial institutions’ own provisions. Two broad conclusions can be drawn from Table 1:

- No other European country has changed the structure of its banking sector to the degree of that registered in Spain. This restructuring has helped match the supply of financial services to demand, an issue that looks likely to remain unresolved elsewhere in Europe for some time to come.

- The year 2012 was a turning point in the volume of resources devoted to recapitalisations and cleaning up balance sheets. Institutions’ provisions have, in fact, played a fundamental role.

It is worth noting that any effort by banks to restructure and clean up their balance sheets reflects (or in some cases, translates into) another parallel effort by Spanish households and firms. Thus, for example, the efforts made to pay down the debt are evident from the fact that debt levels fell by 453 billion euros between June 2010 and June 2015.

In any event, as far as the structure is concerned, some additional indicators can help better explain recent developments and point to future trends.

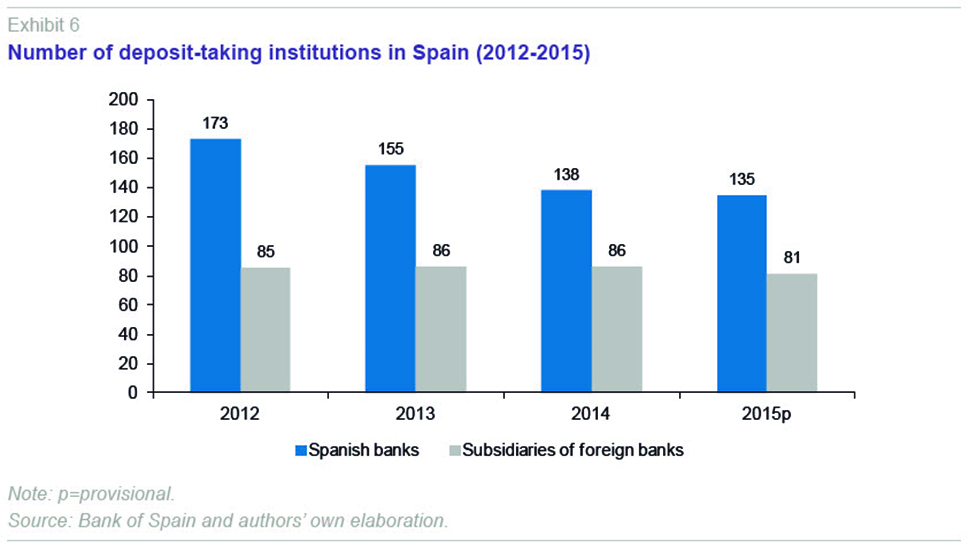

Exhibit 6 shows how the number of Spanish deposit-taking institutions has fallen from 173 in 2012 to 135 in 2015, while the number of subsidiaries of foreign banks has declined from 85 to 81. The Spanish banks include the 53 mentioned in Table 1, which account for the bulk of activity. The number of foreign subsidiaries initially increased, but then fell when a significant number of European banks finally embarked on restructuring plans in 2014 and 2015.

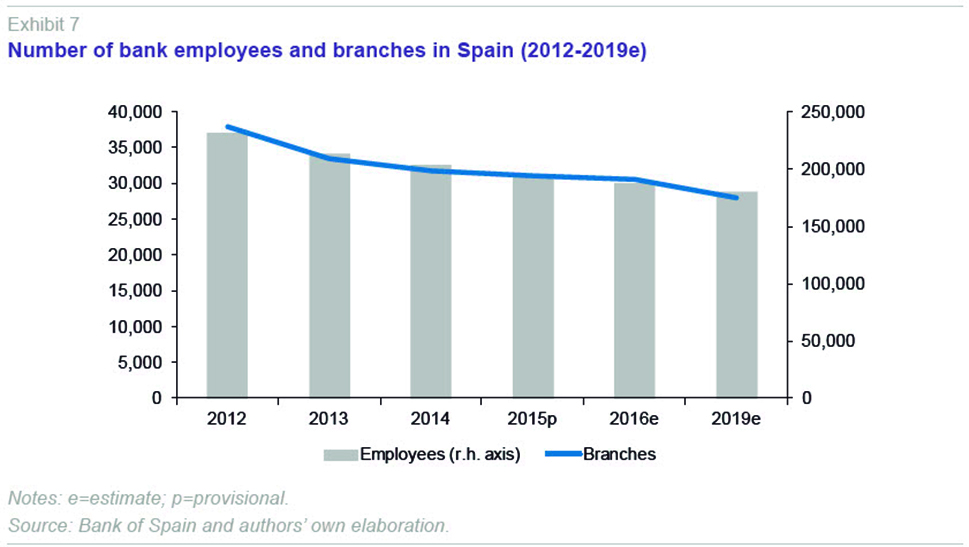

The decline in the number of competitors has been accompanied by a significant adjustment in operational structure (Exhibit 7). Thus, the number of employees has dropped from 231,389 in 2012 to an estimated 194,688 at the end of 2015. The number of branches has also been cut from 37,903 in 2012 to 31,021 in 2015. It should be noted that these adjustments are still ongoing − although the process is not as intense as in previous years − such that by 2019, the number of branches could be around 28,000 and the number of employees 180,000.

Some of these cuts could be considered ‘organic’ in the sense that they are geared towards matching supply to demand in a context in which significant technological change is also under way (this started before the crisis, but is increasingly present in banking operations) and there is growing competition from non-bank operators.

Another part of the structural change may be due to expectations of new bank integration processes in Spain. On this point it is difficult to discern which specific institutions will be affected and how many new major banking groups will be competing in Spain. However, at the geographical scale at which retail financial services compete, the degree of concentration is not as important as the contestability or competitive intensity between rivals at the provincial or regional level. There is international evidence showing there to be sectors in which just five main institutions operate (such as Canada) that are as −or more− competitive than others in which there are hundreds (such as the United States or Germany).

Financing conditions and new dimensions of bank-business relations

As discussed in the preceding sections, the financing conditions for businesses and households are finally improving in the aftermath of the crisis, albeit slowly. The data for businesses confirm that:

- Banks are targeting an increasing share of their new lending to SMEs.

- Interest rates have fallen significantly.

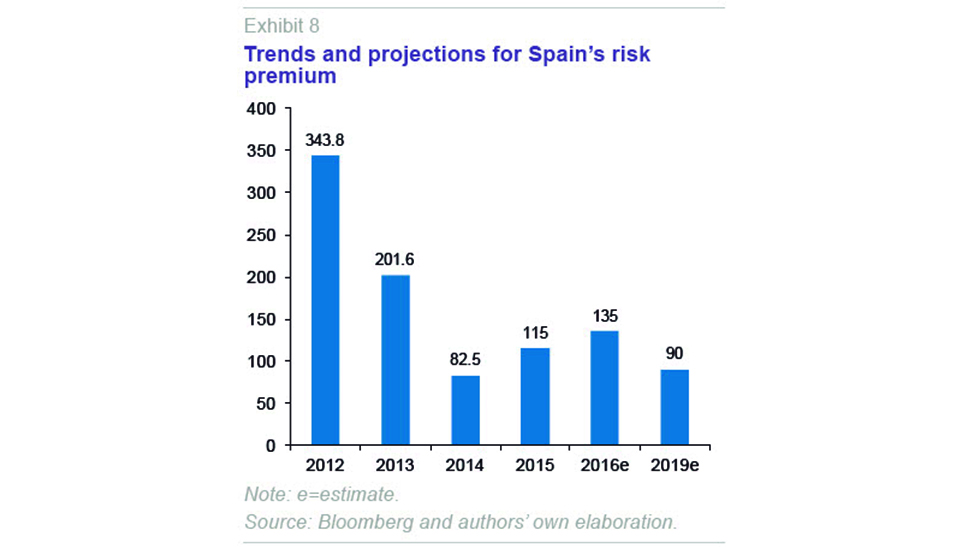

Falling financing costs are basically being driven by the European Central Bank’s expansionary monetary policy and the extraordinary liquidity injections it has been making in recent years. However, it is also worth noting the reduction in country risk − due to its impact on the corporate sector’s ability to obtain finance. Many Spanish companies had difficulty accessing finance throughout 2012 and into 2013 as a result of rising sovereign risk. As Exhibit 8 shows, the risk premium − the spread between Spanish and German ten-year bonds − fell by more than 220 basis points between 2012 and 2015. The risk premium may rise in 2016, at least during the first half of the year, unless political instability is resolved. Over the longer-term, towards 2019, the risk premium is likely to be below 100 basis points, although the horizon is more than long enough for a variety of factors to have an impact on country risk.

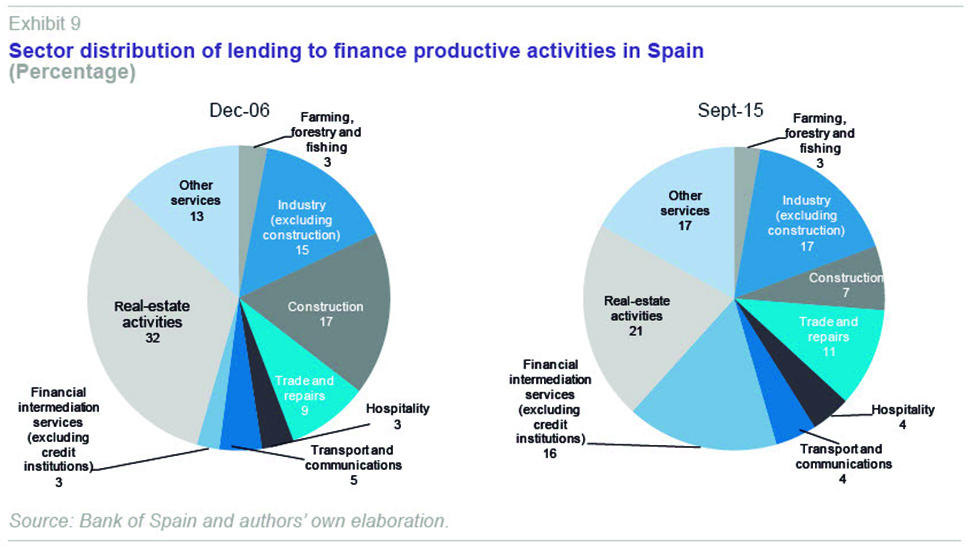

In the context of better financing conditions for businesses, there has also been a change in the composition of the sectors benefiting from bank credit (Exhibit 9). Comparing 2006 (pre-crisis) with the situation in September 2015, lending to real-estate activities can be seen to have declined from 32% to 21% and construction lending from 17% to 7%. The share of lending to industry has risen from 15% to 17%, however. Trade (from 9% to 11%) and other services (from 13% to 17%) have also come to account for a larger share of borrowing. This redistribution across sectors is in line with a process of risk redistribution, reducing the excessive exposure to a single sector (construction and real-estate).

In any event, a fundamental area of change in relations between banks and businesses in Spain lies beyond new lending operations. Namely in the resolution of existing debts. This is an issue of vital importance, not only because it affects how Spanish businesses can reduce their leverage with financial institutions effectively, but also because it determines the viability of a significant number of businesses.

In this regard, Spain recently adopted a number of measures that have led to profound changes in bank-business relations and the process of corporate restructuring.

In 2014, urgent measures were adopted on the refinancing and restructuring of corporate debt, introducing amendments to the law on bankruptcy and civil proceedings to help viable companies renegotiate their debt with the banks or propose debt reductions to avoid bankruptcy proceedings. At present, in 90% of cases, bankruptcy proceedings end with the closure of the business. The bankruptcy law’s requirements were therefore changed so that creditor banks could convert part of their debt (the part that is unsustainable for the company) into equity. This was accompanied by a reduction in the majorities needed for agreements to be binding, so as to make it harder for minority shareholders to block them. The effect of refinancing agreements with a court endorsement can now be extended to dissenting creditors. Banks are also given priority, behind the social security and the tax collection agency, in the event of bankruptcy proceedings.

Banks’ accounting rules have been changed so that when they swap a company’s debt for equity and the company is deemed to be a going concern, they can release the provisions set aside for the loans. The former requirement that an offer for 100% of a company’s capital had to be made when a holding exceeded the 30% threshold has also been eliminated.

The measures adopted have been particularly pragmatic in the context of business resolution processes which are, however, not exclusive to Spain. Indeed, since the end of 2015, there has been increasing concern over companies with a high franchise value in sectors, such as energy or technology that have significant debt levels across various countries. The restructuring options offered by the reforms adopted in Spain may represent an opportunity to establish the viability of these companies rather than end in their closure.

Payment methods as a vehicle for technological change

One last factor broadly impacting the Spanish banking sector is technology. Based on the trend seen in most service sectors, whereby new IT-based channels are being used to offer services, with low or zero marginal costs, new ways in which businesses and individuals can obtain funds have emerged. These include on-line business-to-business (B2B) lending, crowd-funding, and mini-bonds. This diversity of funding sources is challenging banks’ continued hegemony in credit markets. Considering the emphasis from both the public and private domains on the growing importance of alternative funding channels, it is plausible that banks will have a diminishing role in the economy in the not-too-distant future. However, this will not necessarily be the case. Alternative funding channels may eventually complement rather than replace traditional bank finance.

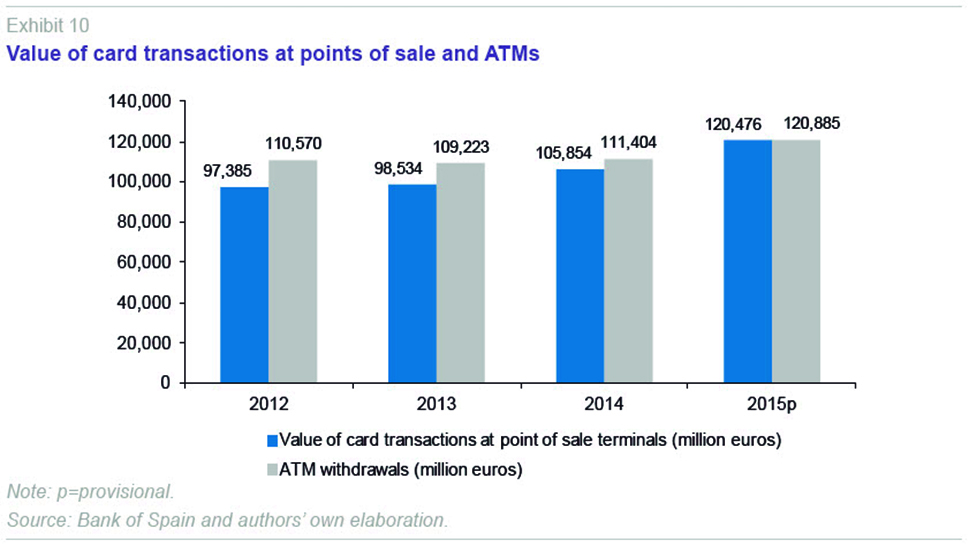

In any event, while alternative financing systems seek to establish themselves both within and outside the banking sector, technological change continues to be focused on payment methods as has largely been the case in recent years. The clearest example is given by card transactions (debit or credit). As Exhibit 10 indicates, after several difficult years as a result of the crisis, card transactions have been increasing since 2012. Volumes came to 97,385 million euros in 2012 and are estimated to rise to 120,476 million euros at the end of 2015. This amount is still slightly less than the total for cash transactions, which are estimated to have come to 120,885 million euros at the end of 2015.

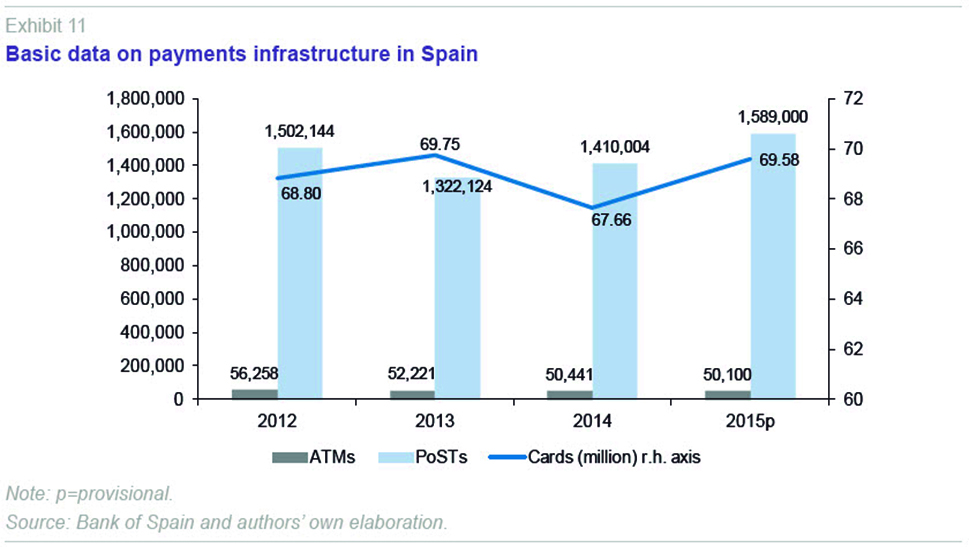

The transition from cash to electronic means of payment is progressing in Spain, although not as fast as might be desired. This issue is by no means a trivial one either for banks or society as a whole. The use of electronic instruments enables substantial savings and has additional advantages in terms of security and in the fight against tax evasion. Although levels of penetration differ, the difficulty of fostering this transition to electronic means of payment is worldwide. Alternatives are increasingly being discussed to encourage the shift, such as tax incentives or making card payments compulsory for certain services. For Spanish financial institutions, this transition is important because, among other things, the country’s investments in payment infrastructure have been among the world’s highest for many years. In any event, there is an additional aspect that needs to be taken into account in the development of this technology. The favoured medium for the development of card payments is the point of sale terminal (PoST). This contrasts with the cash dispenser (ATM), which although it provides other services, encourages cash withdrawals. Financial institutions have two different coexisting objectives: reducing basic branch services that can be performed using ATMs and encouraging the use of PoS terminals. In any event, as Exhibit 11 shows, Spanish financial institutions have reduced their numbers of ATMs from 56,258 in 2012 to an estimated 50,100 at the end of 2015. Meanwhile, the number of PoS terminals has risen from 1,502,144 to 1,589,000. The number of cards held by Spanish consumers rose from 68.8 million to 69.58 million over the same period.

The coming years will see the emergence of new financial technologies, such as mobile payments, which, although they have already been implemented, have yet to achieve widespread adoption. These new devices will coexist with those of other alternative providers, such as Apple Pay and Samsung Pay. This means that banking intermediaries will also face competition from non-bank operators in the payments area in the years ahead.

Conclusions

This article has reviewed the main changes that have taken place in the Spanish financial system − focusing particularly on the banking sector −since 2012, and the outlook − within the constraints of current political uncertainty − over the next four years. At least five conclusions can be drawn from this analysis:

- The political instability following the December 2015 general elections has become a short and medium-term destabilising factor whose long-term consequences are difficult to predict. There are no grounds for concern about financial stability, but it is nevertheless the case that a context of political uncertainty is a brake on investment and funding flows.

- Banking activity between 2012 and 2015 was characterised by restructuring, recapitalisation, reform and recourse to the Eurosystem. Between 2016 and 2019 a progressive return to positive year-on-year credit growth can be expected, compatible with continuing integration and growing regulatory pressure as progress is made towards full compliance with the Basel III solvency and liquidity requirements.

- Substantial efforts have been made to manage defaults and set aside provisions for impaired assets. The default rate can be expected to drop from 8% in 2016 to around 3% by 2019.

- The structure of the banking market has changed substantially, with 53 institutions being involved in integration processes resulting in 14 banking groups. Between 2008 and 2012, Spain cut its number of bank branches by 17%, compared with a cut of 8% in Germany, 5% in Italy, and 3% in France.

- The challenge for the next four years lies in the business, with a risk management structure that is more targeted to, and customised for, SMEs and a stronger focus on the effects of technological change in retail services, beginning with efforts to achieve widespread adoption of electronic payments, perhaps even with public policy support to incentivise less use of cash.

Santiago Carbó Valverde. Bangor Business School and Funcas

Francisco Rodríguez Fernández. University of Granada and Funcas