Social Security budget for 2022: Short-term state support yet a need for structural reform

Thanks to the increase in contributions, the Social Security deficit is projected to fall to 0.5% in 2022. However, the long-term sustainability of Spain’s Social Security will require action on both the expenditure and revenue side that goes beyond recent initiatives.

Abstract: The two main developments in the Social Security budget for 2022 are: (i) the implementation of a new method for revaluation of pensions based on prior-year inflation; and, (ii) growth in state transfers to finance the so-called “undue” expenses being funded by the Social Security and help balance its accounts. Despite the sharp growth in pension spending, the increase in contributions from the state via taxes and the forecast growth in contributions, underpinned by the anticipated economic recovery, are expected to drive a reduction in the nominal deficit to 0.5% of GDP in 2022. However, the shortfall in system contributory revenue relative to expenditure will remain at 1.5% of GDP. Correction of the Social Security’s structural deficit in the medium- and long-term will, therefore, require new measures that will necessarily have to combine actions on the revenue side (even after the recently proposed increase in employer contributions) with others on the spending side, with contributory pensions the primary focus of any future reforms.

Introduction

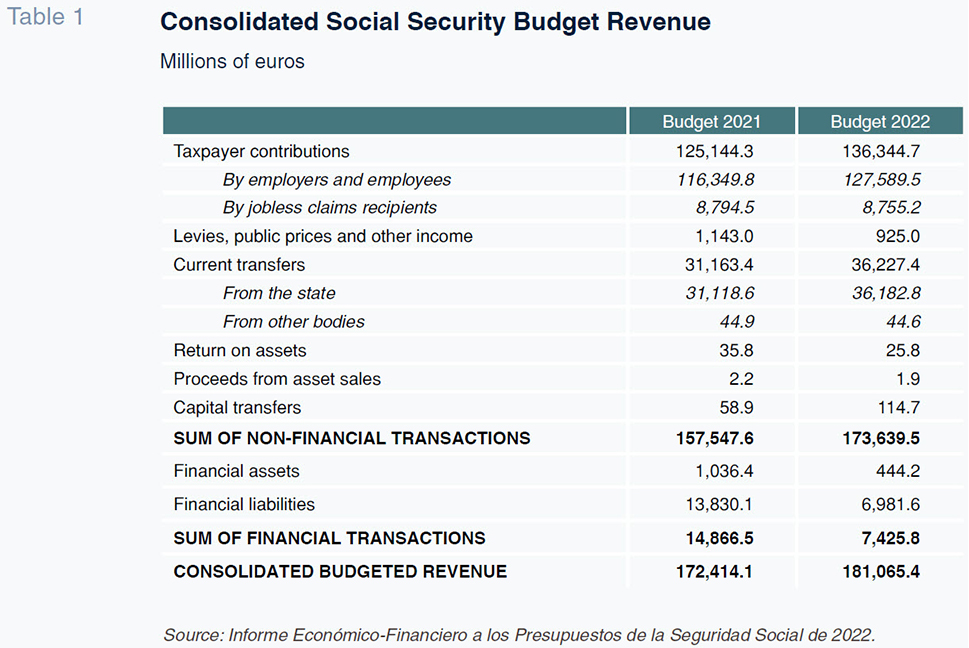

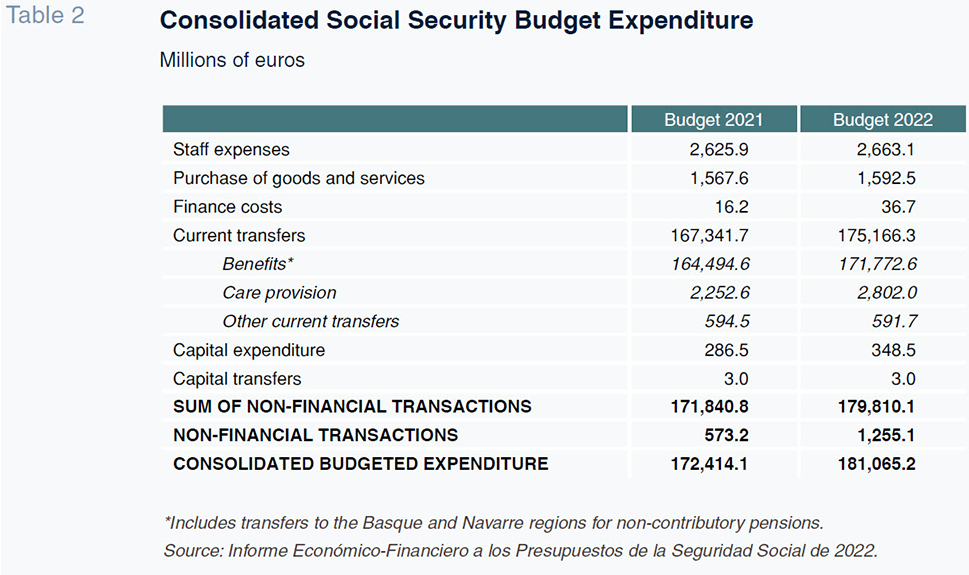

The Social Security administration’s 2022 budget contemplates non-financial expenditure of 179.81 billion euros, growth of 4.6% from 2021. In line with the nature of its functions, the provision of benefits to Spain’s households accounts for the large part of that spending, 171.77 billion euros, which is equivalent to 95.5% of the total. In turn, the system’s overall non-financial income in 2022 is budgeted at 173.64 billion euros, up 10.2% from the revenue budgeted this year. The main revenue sources are social security contributions, at 136.35 billion euros, followed by transfers by the state, at 36.18 billion euros.

The growth differential between revenue and non-financial expenditure (10.2% vs. 4.6%) is attributable to the forecast growth in revenue from contributions of 8.9% and in state transfers of 16.3%, figures that are significantly above the budgeted growth in benefits, of 4.4%. The Social Security deficit is budgeted at 14.29 billion euros in 2021 and is forecast to narrow to 6.17 billion euros next year.

Revenue and expenditure in 2022

A comparison between the revenue forecasts for 2021 and 2022 highlights, above all, the growth in national contributions and in transfers from the state (Table 1). The former calculation is based on the anticipated growth in the number of contributors influenced by the economic recovery, measured in average earned income and across the upper earnings limit. This amount will rise by 1.7% to 4,139.40 euros a month. Meanwhile, the lower earnings limit will be adjusted for the increase in the minimum wage. As for state transfers, the growth stems from the amendment of the General Social Security Act in 2020, which sets new criteria for state transfers to the Social Security, framed by the principle of independence of financing sources.

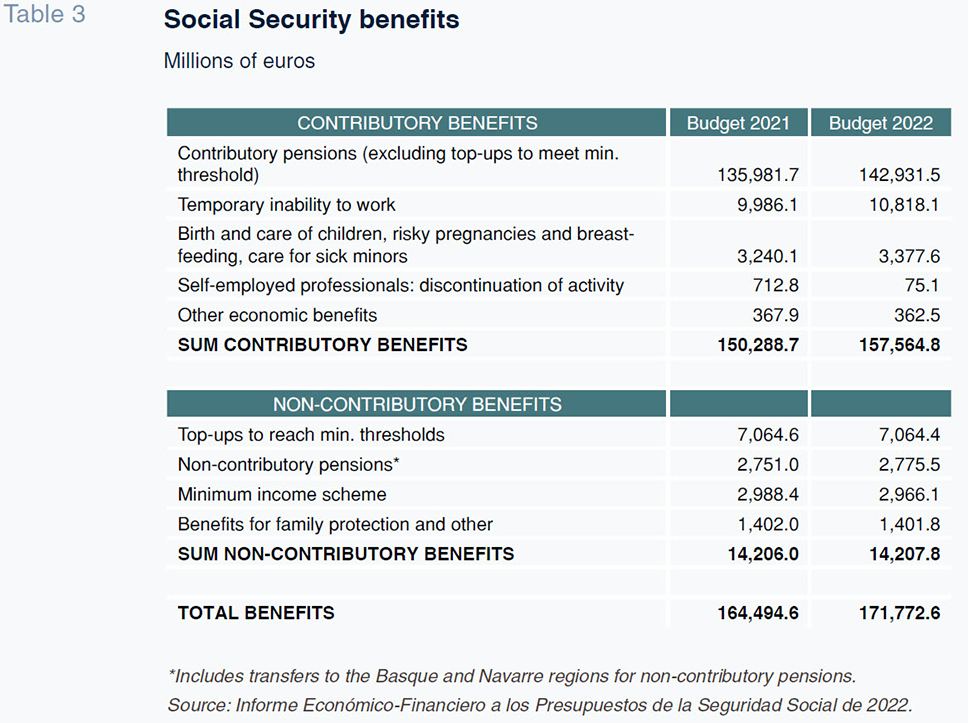

On the spending side (Tables 2 and 3), the growth is attributable to contributory pensions and, to a far smaller degree, the increase in allocations to temporary disability and dependent care benefits. In the case of pensions, three factors underpin the budgeted growth in expenditure: (i) growth in the number of pensioners; (ii) a substitution effect (higher pensions paid to new pensioners relative to those exiting the system); and, (iii) pension revaluation. The fact that a higher number of people with entitlement to a pension will reach retirement age than the number expected to pass away, is expected to drive an increase in the number of pensioners of around 1% in 2022. Based on the monthly 2021 figures released to date, the substitution effect could amount to 1.5%. Lastly, the general pension increase approved by the government –at the average rate of change in CPI in the 12 months to December 2021– could result in a pension hike of around 2.5%. If those assumptions prove correct, spending on contributory pensions would increase by 5% in 2022, which is the figure contemplated in the Social Security budget.

[1] At any rate, the ultimate magnitude of those effects could be affected by the impact of phase one of the pension reforms (currently going through Parliament)

[2] on individuals’ early retirement decisions.

As illustrated in the tables, in 2022, adjustments for inflation will be a key driver of pension spending. Based on the inflation figures through October 2021 (Funcas 2021a) and Funcas’ forecasts for 2022, pensions will be increased by around 2.5%, or by around 3.6 billion euros, in 2022. In addition, the budget for 2021 has to be grossed up by the revaluation guarantee in effect this year, specifically for the difference between final inflation (2.5%) and the initial increase in pensions introduced at the start of the year (0.9%), i.e., around 2.3 billion euros. In total, growth in spending by the Social Security is projected at around 5.9 billion euros, plus another 700 million euros in the state budget corresponding to the increase in the special pension scheme for civil servants for an overall increase in structural public spending of 6.6 billion euros.

Passage of the general state budget for 2022, a process which encompasses the Social Security’s budget, also includes regulatory amendments that affect financial aspects of the pension system in different ways. In addition to the above-mentioned reform in the manner in which contributory pensions are adjusted for inflation, the government has updated the maximum amount (to 7,939 euros a year) of earned income for entitlement to minimum contributory pension top-ups, set new minimum pension thresholds (up 3% from those of last year) and increased by 3% the amount of non-contributory pensions to 5,808.6 euros per annum. In terms of social contributions, the government has increased the upper earnings limit for contributions, which now stands at 4,139.40 euros, and adjusted the minimum threshold by the percentage increase in the minimum wage.

State contributions to a balanced budget: Nominal deficit and contributory deficit

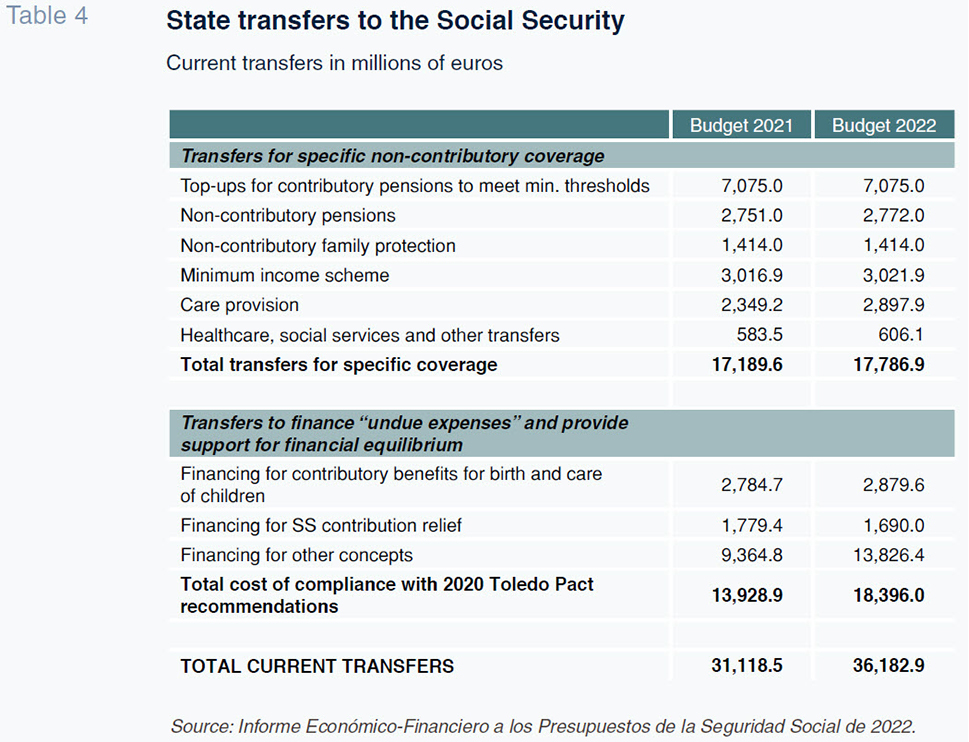

The state’s current transfers to the Social Security are budgeted at 36.18 billion euros in 2022, up 16.3% from 2021 (Table 4). That considerable increase is framed by the effort to finance an increasingly higher percentage of the Social Security’s benefits and services via taxes. A first block of transfers is intended to cover specific types of coverage and stems from the plan to separate sources of financing embarked on following approval of the Toledo Pact in 1995, followed up by Law 24/1997 on the consolidation and rationalisation of the Social Security system. The aim is for the state to cover the country’s non-contributory benefits, which are related to income redistribution and poverty reduction goals. Those benefits include the contributory pension top-ups to reach a minimum threshold, non-contributory pensions, non-contributory family protection benefits, the minimum income scheme and coverage for care provision, among other benefits. In total, that first block sums to 17.79 billion euros in the 2022 budget, which is very similar to the 17.19 billion euros budgeted in 2021 (albeit with the budget for dependency care increasing by 23.4%).

The second block of transfers serves a dual purpose: financing the so-called “undue” expenses and providing support for the Social Security’s financial equilibrium. That second objective was added for the first time in 2018, with an allocation of 1.33 billion euros, and was left in the next two budgets, with allocations of 1.93 billion and 1.33 billion euros in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The 2021 budget, however, changed the concept of the transfer and increased its size to 13.93 billion euros in order to comply with recommendation one of the 2020 Toledo Pact and guarantee the system’s sustainability in the medium- and longer-term. The State Budget Act of 2021 introduced the requirement of an annual transfer to the Social Security to compensate it for the cost implied by reductions in contributions in certain regimes and for certain groups, the coverage of “gaps” in contributions for pension calculation purposes, and other concepts that were not initially specified. The 2022 budget increases the 2021 allocation by a further 32.1% to 18.4 billion euros.

However, the various uses given to these transfers do not only include coverage of “undue” expenses, understood as coverage of social or economic policy goals that do not fit within the classification as “contributory”; they also include other benefits that, while their scope of coverage and size may have been increasing, do form part of the contributory core of the Social Security system. It is reasonable to classify reductions in contributions, the implicit aid given for certain regimes and training contracts, the coverage of contribution “gaps” and the contributory pension top-ups initially conceived of to reduce the gender gap as “undue” functions. In all, they sum to 4.04 billion euros that should not affect contributory pensions. In our opinion, the remaining items, [3] such as the contributory benefit for the birth and care of children, early retirement without pension reduction coefficients, ‘family’ pensions and other contributory benefits, are part of the contributory core, and amount to 14.36 billion euros in total.

The Social Security’s 2022 budget points to a deficit of 6.17 billion euros, down from a deficit of 14.29 billion euros budgeted in 2021. The reduction is attributable to the expected growth in revenue from contributions, coupled with the increase in current transfers from the state, which we have termed the second block of transfers (to cover “undue” expenses and support financial equilibrium). Of the total second block, 14.36 billion euros will generally go to the contributory arena and can therefore be associated with improving the Social Security’s financial health, the “adjusted” deficit in 2022. A proxy for the contributory system deficit would be 20.53 billion euros which is equivalent to 1.6% of the GDP forecast that year by Funcas (2021b). Running the numbers in the same way for 2021, discounting the impact of COVID-19 on the transfers, the “adjusted” contributory deficit would be 2.1% of GDP, higher than that forecast for 2022 on account of lower revenue from contributions and lower transfers of a general nature.

The Social Security has been running a contributory deficit of around 1.5% of GDP on average since 2015. The increase in financing from taxes corrects some of the current imbalance but slightly undermines the contributory nature of the pension system, the largest component of Social Security spending. Meanwhile, the effort made by the state to ensure higher contributions on an ongoing basis will exert pressure on the finances of the state, which, according to the draft budget presented by the government (2021a), will end 2022 with a structural deficit of 4.5% of GDP.

Pension system reform initiatives

The key initiatives of the pension reforms proposed by the government are included in the Operational Arrangements between Spain and the European Commission with respect to the country’s Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan (European Commission, 2021). The government is pursuing the Social Security financial sustainability challenge from a dual perspective. In the short-term, the quest for a balanced budget is being tackled via an increase in state transfers, as stipulated in Law 11/2020 on the general state budget for 2021. The goal is to close the current deficit by covering all of the so-called “undue” expenses, estimated by the government at 22.87 billion euros, from taxes. In reality, to avoid a deficit in 2022, the generalist transfers (i.e., not for specific coverage purposes) would have to exceed 24 billion euros.

In the medium- and longer-term, sustainability requires more far-reaching changes to the system’s parameters. To start, the government would need to eliminate the two axes on which the reforms of 2013 were based: the pension revaluation index and the sustainability factor. The government has divided its strategy into two phases. The first phase entails a draft bill on ensuring pension purchasing power and other measures for reinforcing the financial and social sustainability of the public pension system. At the heart of that reform is an effort to align the effective age of retirement with the ordinary age for entitlement to a pension [4] by revising the pension reduction coefficients in the event of early retirement, whether voluntary or involuntary. In turn, the new measures seek to incentivise working past the state pension age and revise the terms of partial retirement, whereby people can take some of their pension and carry on working. Application of the reduction coefficients for early retirement to pension amounts rather than the regulatory base will affect the largest pensions which were not previously reduced (the changes will, however, be introduced on a staggered basis over a period of 10 years). The draft legislation is rounded out with a new mechanism for increasing pensions annually based on the average year-on-year rate of inflation during the 12 months to December.

In a second phase, as agreed with the two largest trade unions (but not with the employer associations), the former sustainability factor will be replaced with a so-called intergenerational equity mechanism made up of two components. The first is the provision to the Social Security Reserve Fund of an additional 0.6% of the contribution for common contingencies during a period of 10 years (between 2023 and 2032), with 0.5 percentage points charged to employers and 0.1 percentage points charged to employees. The Fund will be used to finance possible deviations in spending from 2033 with respect to the forecasts set down in the European Commission’s Ageing Report, with an annual drawdown limit equivalent to 0.2% of GDP. The second component similarly kicks in from 2033 and involves a possible reduction in the percentage of pension spending over GDP or an increase in contribution rates in the event that the drawdown of Reserve Fund assets where not sufficient to cover possible shortfalls. The specifics of the proposal will be implemented by means of the amendment of the above Bill which is currently making its way through Parliament.

Pending further details about the reform proposals, two questions spring to mind. Firstly, even if the Social Security manages to balance its budget between 2023 and 2032 with the contributions from the state, it is very likely that pension spending will rise steadily to one percentage point of GDP. This would generate additional financing needs that would not be covered by ordinary contributions, trending virtually in line with GDP. Secondly, assuming average annual growth in the contribution bases for common contingencies of 4% (which is roughly the annual average this century), and assuming an average annual return of 3%, the Reserve Fund by the end of 2032 would stand at around 35 billion euros. In the 10 years after 2032, pension spending will continue to grow by an additional one or two percentage points of GDP. However, the Fund will only be sufficient to cover a very small part of the total projected growth in spending and the annual deficits generated. Therefore, the periodic review of the Social Security’s accounts will require, in all probability, the adoption of measures on the spending side even before the end of the period for endowing the newly created Reserve Fund in 2032.

Notes

Spain’s Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility AIReF (2021), is estimating growth in the number of pensioners at 0.8%, a substitution effect of 1.1% and a pension revaluation of 2.1%, for overall growth in pension spending of 4%.

Bill on ensuring pension purchasing power and other measures for reinforcing the financial and social sustainability of the public pension system.

Refer to Informe económico-financiero a los Presupuestos de la Seguridad Social de 2022, p. 46.

In 2022, the legal retirement age will be 66 years and two months for anyone who has been paying in for less than 37 years and six months, and 65 years for those who have paid in for more than 37 years and six months. The gradual application of the 2011 reforms will lift the legal age of retirement to 67 in 2027 for contributors paying in for less than 38 years and six months and 65 for everyone else. The effective retirement age in 2020 was 64.6 years.

References

Eduardo Bandrés Moliné. Funcas and University of Zaragoza