Tapping into know-how and innovation through corporate venturing

To thrive in an era of rapid technological change, companies have two main options – to innovate from within or to grow externally, through partnerships with innovators. One of the more novel options for external growth is corporate venturing, which blends the financing and expertise from experienced corporates with the fresh ideas and business approaches of start-ups.

Abstract: Intense competition in developed markets has pushed companies to innovate and add value to their offerings. They need to focus their efforts on bringing something new to market, improving their productive processes, enhancing their services and honing their management style. In this environment, corporate venturing provides a tool that ticks all those boxes for investors, while also fostering business initiative. Corporate venturing entails investment by established companies in high-tech or otherwise ground-breaking start-ups. However, it is more than just financing. Corporate venturing provided by enterprises constitutes a formula for innovation articulated around financial and strategic criteria. The two principles converge around the search for returns in the context of new technologies, business models, talent and sources of innovation. In short, corporate venturing does not simply seek returns driven by multiple expansion or M&A-driven returns, as may be the case with private equity or venture capital funds; it also strives to acquire knowledge and know-how and foster collaboration. It is, in sum, a new way of tapping innovation. From the standpoint of entrepreneurs, this formula offers clear-cut advantages in terms of access to the business ecosystem, the corporates’ management experience and contacts, while giving them the ability to scale up their projects, share know-how and tap into growth opportunities. In Spain, the number of start-up investment rounds reached 385 in 2021, which is 78 transactions more than closed in 2020 with a record level of funds raised totalling €4.21 billion. Going forward, the outlook appears bright for this form of corporate cooperation and development.

Introduction

We are going through a period of unprecedented technological transition, replete with changes as convulsive as the digitalisation of our surroundings, blockchain, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI), to name a few. Some of these technologies have been accelerated by the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, and technology is advancing in all sectors of the economy, requiring markets everywhere to relentlessly pursue innovation. In such an environment, a wide variety of opportunities inevitably emerges. The landscape for entrepreneurs and investors alike is fast-changing and dynamic and requires specific skillsets, including flexibility and the ability to adapt.

In such an environment, companies are being forced to seek out new strategies in order to meet these demands and remain competitive. Moreover, increased social awareness, and the resulting requirements arising from this trend, is adding another virtue to corporate venturing as it is a model that supports business creation and fosters ground-breaking initiatives. These and other questions are pushing established companies to scrutinise the entire spectrum of growth opportunities, and embrace new ways of innovating that can boost returns and respond to the prevailing circumstances.

Two paths to growth: Internal and external development

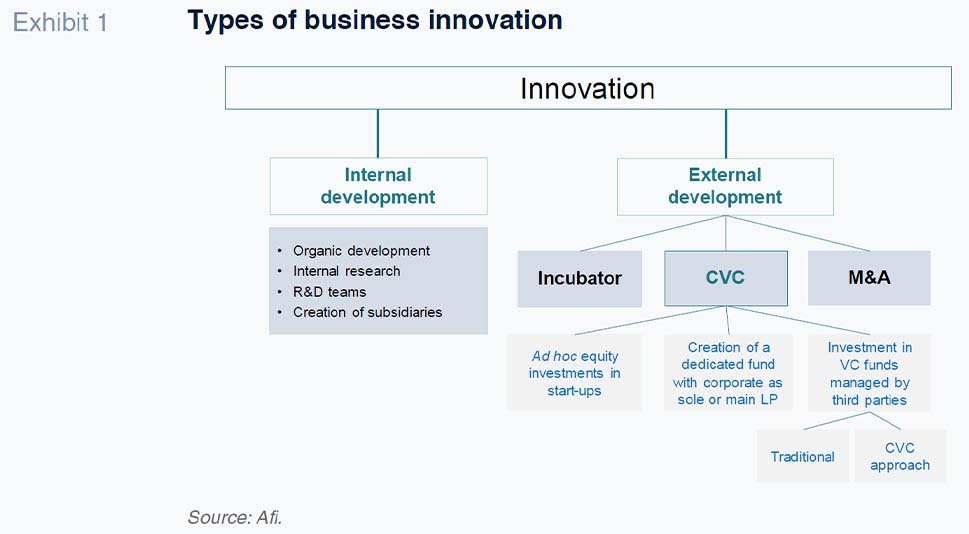

In response to this complex situation and the need to implement innovative processes, companies face two main paths to growth: internal and external development.

Internal development involves tapping innovation through a company’s internal research and development (R&D) capabilities, retaining full control over all projects. However, the fact that legacy companies tend to operate with more static or established structures can make it harder for them to tackle disruptive, paradigmatic change. R&D-led innovation requires the exclusive use of in-house resources and dedicated teams. Both the funds and teams tied up in the R&D effort belong to the company, free from any outside interference.

External development, on the other hand, can be approached in three main ways:

- Incubators. These are platforms created within a company with the goal of spawning new enterprises with innovative ideas (i.e., seed companies) by providing training, advice, access to finance and a network of contacts. Media exposure enhances their positioning without generally, but not always, taking in capital. Incubators are not external arms of the corporate venturers, but rather internal platforms set up by the companies themselves in order to maintain close contact with the entities participating in a given project. The start-ups being incubated are given access to the logistics networks, technology and know-how of the incubator firm, which in turn benefits from the innovation that is developed.

- Mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Here, the idea is to acquire a stable and long-lasting equity interest in an innovative company. If a company purchases a majority stake, it will gain significant control and play an active role in the target’s corporate governance, along with the ability to influence its strategic decisions. The M&A route also offers the ability to incorporate proven businesses and skills faster than would otherwise be possible, which is an advantage in terms of the time needed to create internal propositions from scratch. However, an M&A investment requires more exhaustive analysis of the universe of potential investments, as this route lends itself to a smaller number of transactions than corporate venturing. This, in turn, involves higher levels of risk.

- Corporate venture capital (CVC). As previously defined, corporate venturing constitutes a firm’s investment arm, with a focus on start-ups willing to cede part of their capital in exchange for financing. However, the crux of this form of investing is not just the financing extended or raised via the equity investment, but also purposely includes the synergies that can arise from collaboration between the two parties.

Corporate venture capital: A new way to tap innovation

Operationally, corporate venture investments can be structured in different ways:

- Through ad hoc investments in start-ups in the form of direct equity investments (usually, but not exclusively, minority interests). These are sporadic investments that do not have a genuine corporate venturing programme articulated around pre-defined investment criteria behind them.

- The use of a specific fund set up specifically for corporate venturing purposes. Equity interests and control arrangements vary under this formula. This method is characterised by the fact that a company’s investments are made systematically and articulated around a programme for investing in start-ups. Note that when we talk about the creation of a special-purpose vehicle for corporate venturing, the entity incorporated is usually independent, other than in ownership terms, from the investing firm, i.e., it has its own organisational and reporting structure similar to that of a mutual fund, and a specific investment policy (committed capital, investment timeframes and amounts, target sectors and markets, etc.)

- Investments in third-party venture capital funds specialised in start-ups with high growth potential. Firms tend to select funds with a similar sector focus to their own.

In the first two instances, known as direct corporate venturing, common advantages include ulterior financial and strategic returns, access to disruptive technology and products that are hard to generate internally, direct access to the company’s everyday business management and internal information, ad hoc involvement in decision-making and the scope for taking on co-investors to bring in additional capital and/or strategic support – higher in the case of the Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) route. Among the possible disadvantages, the most obvious are the lack of diversification (albeit higher relative to the M&A route) and the need to devote higher volumes of resources to generate returns. Indeed, it is customary to set up specific teams to spearhead the corporate venturing effort.

As for investing in third-party private equity funds, the scope for portfolio diversification and for value and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) maximisation is higher than via the first two alternatives. Transactions tend to be faster paced and more systematised, but this is at the cost of closer corporate/investor contact with investees, while management is focused exclusively around the generation of financial returns. This is because the manager has a single mandate –to maximise returns– which somewhat undermines one of the prime virtues of corporate venturing: access to innovation. Nevertheless, the investor can, depending on the transparency and access to the management team, get detailed information about the investees and take advantage of that knowledge from a strategic standpoint. In addition, the fund may offer its own investors preferential co-investment rights.

The rest of this paper focuses on the first two corporate venturing options: ad hoc investments in start-ups and the creation of special purpose funds to invest in start-ups, which are the purest manifestations of corporate venturing.

As already noted, those strategies do not pursue purely financial ends, but rather seek strategic gains, such as up-close exposure to new technologies and business models and ways to capture talent and/or innovation capabilities. They offer access to new and highly innovative products, services and techniques that may end up being incorporated into the investor entity’s business model. They also tend to have a positive impact on the corporate’s brand image by shining the spotlight on its engagement with new (sector-related) business and value creation.

For entrepreneurs, corporate venturing provides, first and foremost, funds to finance their development. However, here too, the benefits transcend the financial sphere. The investor firms support their progress by contributing to their business development, opening business opportunities, sharing their experience and know-how, implementing marketing strategies, professionalising their management and lending brand association. All this is vital during the initial phases of a company’s development and is perhaps even more important than the capital the investor injects.

Collaboration and synergies between corporates and start-ups

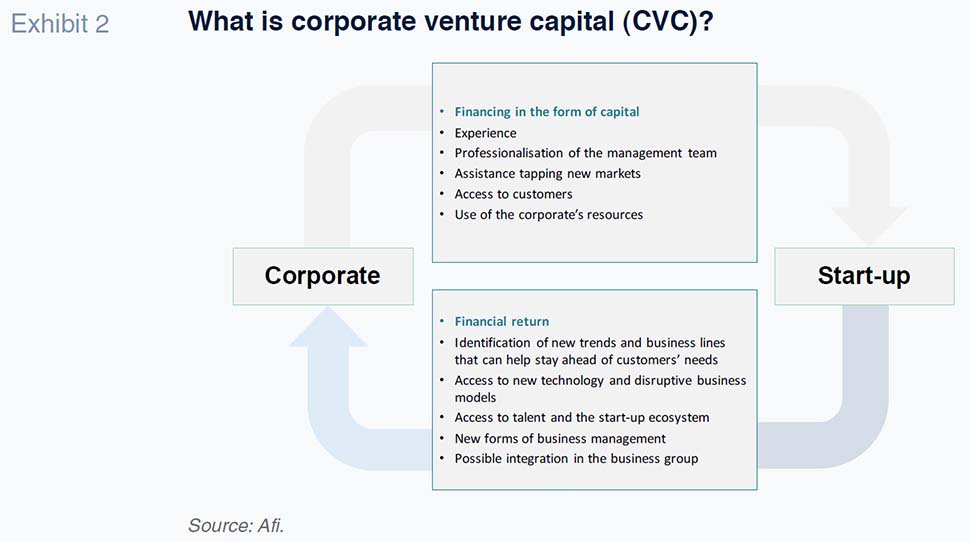

The dual investment-innovation dynamic intrinsic to corporate venturing can unlock strategic synergies. The synergies in the fields of innovation and know-how are of particular interest.

From the corporate investor’s standpoint, beyond a possible financial return, potential benefits include:

- Identification of new trends and business lines that can help it stay ahead of their customers’ needs. Direct contact with start-ups brings the corporates a fresh perspective, providing them with visibility into new market trends and how to satisfy their customers’ needs.

- Access to technology and disruptive business models. Businesses with established cultures and track records tend to get stuck in their ways, but engagement with newer companies can shake up this stagnation. Also, incorporating the technology acquired through corporate venturing in their productive processes opens access to innovation that sometimes cannot be attained by simply investing in R&D.

- Access to talent and the start-up ecosystem. Contrary to appearances, the external talent of the start-up is not meant to replace or undermine the investor’s in-house talent; rather, to stimulate competition between the two teams and foster a joint approach to the challenges at hand.

- New forms of business management. The manner in which start-ups and corporates approach the culture of a business tends to differ, and corporate venturing provides the opportunity to meld these outlooks to enrich cooperation between the two firms. Just as the investing corporate contributes experience and know-how to the management of the investee, a matter we will discuss further on, the latter can bring a fresher and more creative decision-making approach.

- Possible integration in the business group. In the event that the synergies between the two parties end up being significant and they come to view their collaboration as long-lasting, the possibility of integrating the start-up into the business group becomes worth assessing. Such a development not only implies a clear-cut more advantageous than R&D investing in financial terms, it also represents the successful culmination of a joint collaboration and growth process.

Secondly, the advantages for the start-up include the following:

- Experience. The habits and capabilities established by the corporate over its business trajectory (which are sometimes very long) are immediately transferred in the form of information, know-how and support for the start-up, providing valuable assistance for its business activity.

- Professionalisation of the management team. Just as the start-up can shake up the way processes are managed, the investing entity typically has a solid management style and track record to offer that the investee can avail themselves of as they see fit.

- Use of corporate resources. Corporate assets, specifically teams, resources and financial wherewithal, can also be used by the start-up. Some of the formalities and costs the start-up faces can be overwhelming and the corporate venturer can lend financial support.

- Assistance tapping new markets. Beyond the specific use that may be given to the funds raised during the financing round, which often include growth in new markets, the business activities of the investing corporate often offer opportunities for diversification in different sectors and even geographies, and the association between the two firms provides a reputational gain for the start-up.

- Access to customers. Investees gain access to a new network of contacts once they begin to collaborate with the investor.

Corporate venture capital around the world: Origins and current situation

Although it is difficult to pinpoint the exact origins of this approach to innovation, there are examples of CVC dating to the early twentieth century, such as the acquisition of a start-up at the time, General Motors, by DuPont. One hundred years on, corporate venturing continues to register vigorous growth.

In fact, corporate venturing is currently at its most buoyant, garnering a lot of media attention. According to JCR (2020), the number of publications about CVC increased by 18% between 2015 and 2019 and was mentioned in the media over three times more frequently and has been covered at prestigious conferences such as the Mobile World Congress.

CB Insights (2020) reports that, despite the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the volume of corporate venture investments increased by 23% year-on-year in 2020 to $73 billion worldwide. That momentum remains ongoing, with corporate venture investments hitting a new record in 2021 (CB Insights, 2021). In the first half of 2021 alone, CVC transactions amounted to $79 billion, representing approximately 2,100 deals.

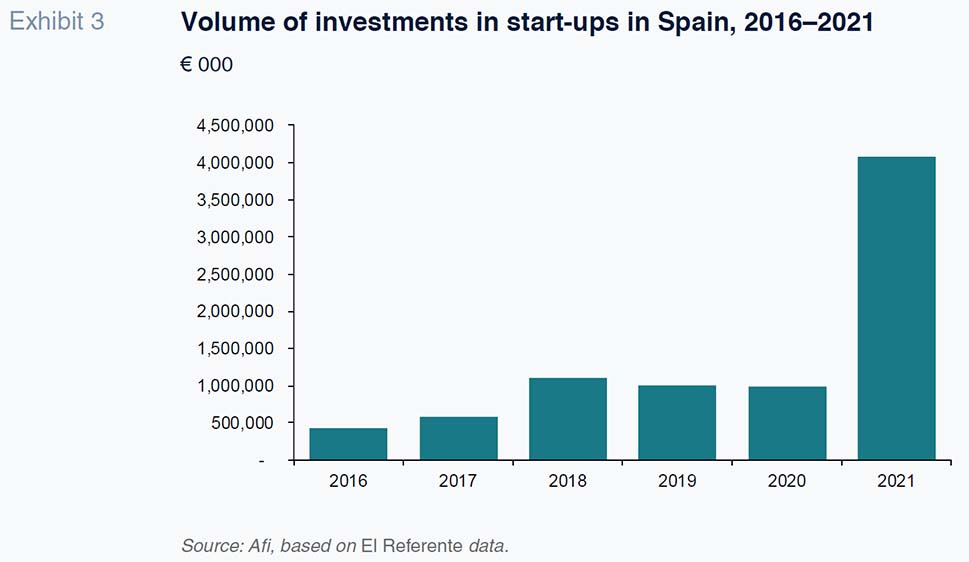

In Spain, according to data published by El Referente (2021), the number of start-up investment rounds reached 385 in 2021 (real data as of December), which is 78 transactions more than closed in 2020. As for the volume invested in Spain, 2021 was also a record year, with funds raised totalling €4.21 billion. To put that figure in context, the volume of investments raised in 2021 alone was higher than the volume accumulated during the three previous years, which just topped the €3 billion mark.

Underpinning these metrics is exponential growth in the number of investment arms created by all sorts of companies.

Some of the highest profile examples on the international stage include Intel, Microsoft and Google. In the early 1990s, Intel set up its corporate venturing division called Intel Capital (formerly CBD), which is currently one of the most sophisticated in the market. In total, Intel’s corporate investment arm has created four investment funds with a particular focus on technology start-ups (telecommunications and software infrastructure). The number of investments made over the life of the division totals nearly 1,900, with exits totalling 570, and valued at over $150 billion.

Technology giant Google created Google Ventures in 2009 to invest in sectors such as e-commerce, health and life sciences, software, cybersecurity, developer operations, data analysis, AI, robotics and quantum computing. Today, it has invested in over 300 companies with more than $8 billion under management, having overseen 48 exits via IPOs and completed more than 180 M&A transactions.

Back in 2016, Microsoft set up a fund to invest in early-stage enterprise software companies known as M12 (formerly Microsoft Ventures). The vehicle invests in start-ups with a focus on business applications, cloud infrastructure, cybersecurity and identity, data analysis and AI, developer tools and healthcare and life sciences, to name a few. Since its creation, Microsoft’s CVC arm has invested in over 100 start-ups, notably including Aqua, WorkSpan, 1910 Genetics and Acerta.

Here in Europe, Siemens’ CVC programme stands out. The German tech company set up its dedicated division, Next47, in 2016, focusing on start-ups devoted to AI and decentralised electrification. Next47 boasts €1 billion of funding and currently has over 35 start-ups in its portfolio.

The Spanish market has also seen its fair share of corporate venturing, with several large and medium-sized enterprises putting significant amounts into their various vehicles across a variety of sectors including the automotive, energy, retail, tourism, financial and tech industries, as well as the circular economy.

In the financial sector, both Santander and BBVA are active in CVC. The former launched its first investment arm, Santander InnoVentures, in July 2014, endowing it with €100 million. It was replaced by a new fund in 2020, Mouro Capital (€400 million), with a mission to invest above all in fintech start-ups. BBVA, meanwhile, in addition to its annual innovation programme for entrepreneurs, Open Talent, finances fintech start-ups via the North American private equity manager, Propel Venture Partners. The Spanish bank has also entered the Chinese innovation market, specifically the AI segment, after investing $50 million in Sinovation Fund IV (Sinovation Ventures). This was an example of a corporate investment in a private equity fund managed by third parties, the third avenue of external development.

As for the universe of non-financial corporates, the efforts of Iberdrola and Telefónica stand out. Since 2008, the former has been focusing, through its investment arm, Perseo, on financing projects that seek to make the energy model sustainable, with a total budget of €125 million. The latter has been managing a genuine CVC ecosystem since 2016 via Telefónica Open Future, which focuses on early-stage start-ups – Telefónica Innovation Ventures, which invests directly in technology start-ups and indirectly via the main private equity funds in which TIV is in turn an investor; and Telefónica Tech Ventures, which focuses on start-ups in the cybersecurity field.

A newer example of corporate venturing in the industrial arena is Enagas whose dedicated Emprende division searches for new business models aligned with its diversification strategy and its goal of adopting disruptive technology early on. Enagas’ effort is subdivided into two programmes: Open Innovation Projects, which seeks innovation in collaboration with technology centres, universities, suppliers and public institutions; and Ventures, through which the energy company invests directly in start-ups, with a current portfolio of 14 investees and another eight under incubation.

While we have only provided examples of large multinational corporates, an increasing number of medium-sized companies are also rolling out corporate venture programmes, with the aim of building a position in niches of interest to their sectors or in adjacent industries of importance to their future strategies. Medium-sized enterprises stand to benefit, in particular, from corporate venturing thanks to the greater savings compared to in-house R&D investments and greater efficiency in terms of tapping technology and innovation.

Conclusions

Intense competition prevailing across developed markets has pushed companies to innovate and add value to their offerings. They need to focus their efforts on bringing something new to market, improving their productive processes, enhancing their services and honing their management style. In this environment, corporate venturing provides a tool that ticks all those boxes for investors while also fostering business initiative.

Corporate venturing is clearly a win-win for corporates and start-ups alike. It is a model that gives corporates access to innovation and technology, both of which are destined to be cornerstones of their business activities for years to come. From the standpoint of entrepreneurs, this formula offers clearcut advantages in terms of access to the business ecosystem, the corporates’ management experience and contact networks, while giving them the ability to scale up their projects, share know-how and tap into growth opportunities.

The corporate venturing mechanism appears to be a clear formula for satisfying investors’ innovation requirements. Going forward, the outlook seems bright for this form of corporate cooperation and development, not only to bring businesses closer to cutting-edge technology, but also to tap into alternative talent and management approaches whereby companies with markedly different experience and maturity collaborate to promote enterprise and business creation.

References

BBVA OPEN TALENT (2021). Open talent platform metrics.

https://openinnovation.bbva.com/es/open-talentCB INSIGHTS (2020). The 2020 Global CVC Report.

https://www.cbinsights.com/research/report/corporate-venture-capital-trends-2020/CB INSIGHTS (2021). The 2021 Mid-Year Global CVC Report.

https://www.cbinsights.com/research/report/corporate-venture-capital-trends-h1-2021/EL REFERENTE (2021).

https://elreferente.es/inversiones/inversion-startups-anual/ENAGAS EMPRENDE (2021). Enagas Emprende portfolio and metrics.

https://emprende.enagas.es/GV (2021). Google Ventures portfolio and metrics.

https://www.gv.com/INTEL CAPITAL (2021). Intel Capital portfolio and metrics.

https://www.intelcapital.com/#stats

M12 (2021). M12 portfolio and metrics.

https://m12.vc/MOURO CAPITAL (2021). Mouro Capital portfolio and metrics.

https://www.mourocapital.com/NEXT47 (2021). Next47 portfolio and metrics.

https://next47.com/SIOTA, J., ALUNNI, A., RIVEROS-CHACÓN, P., WILSON, M. and

DINNETZ, M. K. (2020).

Corporate Venturing, Insights for European Leaders in Government, University and Industry. Publications Office of the European Union.

TELEFÓNICA (2021). Telefónica Innovation Ventures.

https://www.telefonica.com/es/compromiso/innovacion/telefonica-ventures/

Ignacio Astorqui, Isabel Gaya and Íñigo Morón. A.F.I. – Analistas Financieros Internacionales, S.A.