Spain and the European Recovery Plan

Given the impact of COVID-19 on Spain’s economy and the country’s fiscal constraints, the ability to access EU-level funding will be key to Spain’s recovery. While there are numerous initiatives Spain could benefit from, the EU Commission will want to see evidence of how this funding will support its twin green and digital transition objectives.

Abstract: OECD forecasts indicate that Spain is one of the countries most impacted by COVID-19. However, its fiscal stimulus measures are small in comparison with other countries, such as the UK and Germany. For this reason, Spain’s recovery will rely heavily on support from EU funds. Given the time-sensitive nature of responding to the pandemic’s economic consequences and the schedule of European Recovery Plan payments, it is essential that Spain accesses other EU funding initiatives. The Spanish government has already expressed its desire to use the SURE scheme, which will be available until the end of 2022, and may also use the ESM credit line, which would provide Spain with 10-year financing on more attractive terms than those offered by the financial markets. However, the ability to tap these EU initiatives will depend on Spain’s capacity to demonstrate the allocation of funds to support the EU’s twin green and digital transition objectives.

Introduction

The OECD’s most recent forecasts (2020) suggest that Spain, France and Italy will be the advanced economies hit hardest by the coronavirus crisis. The OECD has estimated a GDP contraction of over 11% in 2020, and potentially over 14% in the event of a second wave. The IMF forecasts (2020) point in a similar direction, with a contraction in GDP of between 12.5% and 12.8% projected this year in all three countries.

So far, the economic policy response has been faster and more on target than in prior crises. However, the Spanish public sector’s budgetary fire-power faces two comparative disadvantages: a structural deficit of around 3% of GDP, one of the highest in the European Union; and a public debt to GDP ratio of 95.5% at the end of 2019, more than 17 percentage points above the EU-27 average.

The comparison between the public funds earmarked by the core eurozone countries to address the crisis and the impact on their economies highlights the differing fiscal wherewithal for tackling the problem, measured not only by the current state of their public finances (deficit and debt) but also the market’s assessment of the sustainability of those finances, whether via the credit ratings assigned to the debt they issue or the risk premiums priced into their debt instruments.

According to the calculations performed by Anderson

et al. (2020), Spain’s fiscal stimulus measures account for 3.7% of 2019 GDP, which is below levels observed in France (4.4%), the UK (8.0%), the US (9.1%) or Germany (13.3%). The deferral of tax and social security payments in Spain offers an even starker picture, accounting for 0.8% of GDP, far behind Italy (13.2%), France (8.7%) and, again, Germany (7.3%). Lastly, the total funds mobilised via public support mechanisms for the provision of liquidity rank Spain somewhere in the middle (9.2%), well behind Italy (32.1%), Germany (27.2%), the UK (15.4%) and France (14.2%). Countries hit very hard by the pandemic have not been able to respond with fiscal measures in proportion to the intensity of the economic shock they are suffering due to their relatively weaker fiscal position.

[1]

As a result, to avoid an incomplete and asymmetric recovery from the crisis in Europe, it is vital to formulate a strategy that helps member states recover their pre-crisis levels of growth and employment without having to depend on their own financial muscle. As the European Commission itself has acknowledged, such a strategy would also sidestep the negative consequences of an uneven recovery on the internal market and the European project itself.

The Commission’s proposal (2020a, 2020b), while having garnered broad political support within the Union, has been subject to major changes by the European Council held on July 17th-21st. Four aspects were generating debate: the size of the programme and its financing; the mix between direct aid (grants) and loans; the terms and conditions; and, the criteria for allocation among the various countries.

The aim of this paper is to review the content (programmes, budget assignations, execution timeframe, criteria for allocating the funds by country) of the European Recovery Plan as part of the broader European programme to help member states tackle the costs of the health and economic crisis, with particular focus on the opportunities and challenges it poses for Spain.

European funds for supporting income and kick-starting the economic recovery

Europe, heavily criticised for its tardiness and lack of determination in tackling the Great Recession, has reacted decisively to the challenges posed by this unprecedented crisis. The first to react was the European Central Bank (ECB) with a new 750 billion-euro asset purchase programme (PEPP), which it approved in March, granting greater flexibility in terms of asset eligibility and allocation among jurisdictions than previous bond buying initiatives. On June 4th, the ECB increased the size of the programme by 600 billion euros and extended its application until at least the end of June 2021.

The European Union’s response has come in several stages. In mid-March and early April it announced a range of measures, including: activating the Stability and Growth Pact escape clause; allowing more flexible use of the EU budget; approving a Temporary Framework for state aid –permitting member states to step in to help with their companies’ liquidity needs–; and, creating a 2.7 billion-euro Emergency Support Instrument for member states’ health systems. It later eased the rules on the use of EU structural funds, eliminating the joint financing obligation and allowing the transfer of money between funds and regions to meet their particular pandemic-related needs. Then, in early May, the scope of the Temporary Framework for state aid was expanded to allow public intervention in the form of the recapitalisation and acquisition of the subordinated debt of non-financial companies.

In parallel, two pan-European programmes were rolled out to provide member states with access to funds on highly favourable terms: (i) a new instrument for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE), with a budget of 100 billion euros in the form of loans; and, (ii) a 240 billion euro loan through the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) designed to finance direct and indirect healthcare and prevention-related costs due to the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, the activities of the European Investment Bank (EIB) were reinforced with a 25 billion euro guarantee fund, which could generate up to 200 billion euros of new financing. The goal of these programmes is to cover potential liquidity needs, albeit at the cost of increasing member states’ borrowings, competing therefore with the availability of funds issued through the ECB.

The SURE Instrument, the ESM credit line, and the EIB guarantee scheme comprise between them a package of measures which can be used by member states throughout 2020 without special conditionality attached. The potential to mobilise 540 billion euros of loans is a good first step in responding swiftly to the fallout from the crisis.

Even though attention has focused almost exclusively on the European Recovery Plan –also known as Next Generation EU– in recent weeks, it is important to note that regardless of how long it takes to finally approve it, and the amendments it may suffer along the way, the financing will not arrive immediately. A reading of the various documents written by the Commission points to a dichotomy between the continuous calls for speed in processing and rolling out the funds as a prerequisite for the success of the overall plan, on the one hand, and the desire to tie the aid to medium- and long-term reform plans aimed at fostering the transition towards a greener, more digital and more resilient economy.

It is for that reason that we believe that the package of measures endorsed by the European Council on April 23rd (SURE, ESM credit line and EIB guarantees) may prove a valuable tool in funding a portion of the national fiscal stimulus measures without having to wait for the European Recovery Plan to materialise. The Spanish government has already expressed its desire to use the SURE scheme, which will be available until the end of 2022, and may also use the ESM line, although it has not yet formally stated its intention to do so. The Spanish Treasury’s financing effort in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis has increased gross issuance by 104.54 billion euros compared to initial forecasts, which would put public debt this year 20 percentage points higher than the debt to GDP ratio observed in 2019.

However, as the ESM itself has noted (2020a), despite the increase in debt triggered by the coronavirus crisis, Spain’s public debt is sustainable in the medium- to longer- term (10 years). Specifically, 50% of its debt is held by residents and the take-up in the markets for recent Treasury issues, which were raised on very favourable terms, has been strong. In addition, the ECB’s intervention in the form of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) is playing a key role in stabilising the eurozone’s bond markets.

Without getting into political considerations, the use of the ESM credit line set to support businesses during the crisis could facilitate funding equivalent to up to 2% of Spanish GDP (nearly 25 billion euros) at below-market rates. Moreover, it could be made available immediately in exchange for simply committing to reinforce the Spanish economy’s economic and financial fundamentals. By way of comparison, the Spanish government has approved a 16 billion euro COVID-19 fund for transfer to the regions to finance the pandemic’s main costs and the associated collapse in revenue.

The ESM funds are, therefore, an alternative that is not subject to special conditionality rules and are available if necessary to support the healthcare system as it grapples with the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19. The credit line would potentially provide 10-year financing at a total cost equivalent to 0.07% -0.08% for seven-year paper. At least 11 countries in the eurozone, including Spain, would be able to secure financing on more attractive terms than those offered by financial markets (ESM, 2020b).

The European Recovery Plan: Next Generation EU

Having acknowledged the need for more forceful intervention that puts member states on an even footing in terms of their ability to support a recovery, the European Union has drawn up an ambitious Recovery Plan as part of its Multi-Annual Financial Framework. The Plan has the support of France and Germany, who had previously presented an initiative endowed with 500 billion euros and targeted at the sectors and regions most affected by the pandemic.

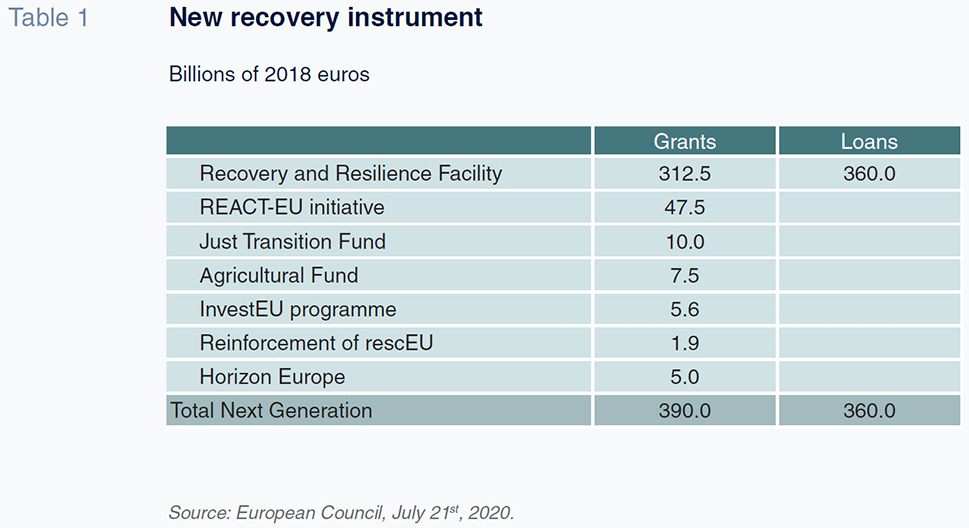

Whereas the 2021-2027 Multi-Annual Financial Framework had a budget of 1.074 trillion, the financial instrument proposed by the Commission in response to the COVID-19 crisis (Next Generation EU) amounts to 750 billion euros between 2021 and 2024. It is a one-off emergency programme that marks a quantitative and qualitative leap in EU dynamics which puts European political and economic policy in a new realm that will require funding, political guidance and, as a prerequisite, consensus between the member states.

Table 1 shows the budget allocations contemplated for each of the initiatives and programmes.

Although the Multi-Annual Financial Framework runs from 2021 to 2027, each line of initiative has its own execution timeline. However, the idea is to allocate the vast majority of the funds earmarked to the Next Generation EU programme before December 31st, 2024, since, as the document itself emphasises, the success of the various initiatives depends not only on the funds and policies put into play but also the speed with which they are deployed.

Although the idea was to concentrate the allocation of 90% of the funds in the next two years, the timetable contemplated in the Next Generation EU programme distributes the actual outlays over a time horizon of at least seven years so that its effective availability will be spread out throughout the entire 2021-2027 Multi-Annual Financial Framework. For example, in the case of the initiatives targeted explicitly at helping member states with their recovery, the 312.5 billion euros included in the form of grants are scheduled for allocation in the amount of 70% in the first two years but their payment during those first two years represented just 24% of the total in the Commission’s proposal.

Spain should be one of the biggest beneficiaries in terms of the volume of funds allocated, due to the impact of COVID-19 on its healthcare system and the devastating impact on GDP and employment levels. However, the allocation criteria contemplated by the European Commission are not in all instances directly related with the prevailing crisis and vary depending on thevarious programmes’ objectives. For the direct aid in support of member states’ recovery efforts (312.5 billion euros in total), the allocation criteria in 2021 and 2022 are: population, the inverse of GDP per capita and the average rate of unemployment during the last five years, all relative to the EU averages and subject to certain limits in the case of the last two variables. In the allocation for 2023, the criteria will be the loss in real GDP observed over 2020 and the cumulative loss over the period 2020-2021. As for the REACT-EU initiative (47.5 billion euros), allocation will be based on the contraction observed in GDP and in total youth unemployment as a result of the pandemic. On the basis of the above criteria, and those that may conceivably be used to allocate funds from the other programmes (not all of which are explicit in the Commission documents), Spain may receive around 72.7 billion euros of grants: 59 billion from the Recovery and Resilience Facility, 12.4 billion from ReactEU and the rest from other programmes. Lastly, given that the allocation of the loans under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (360 billion euros) is subject to a ceiling of 6.8% of each countries’ gross national income, Spain could apply for more than 70 billion euros.

The schedules for the disbursements included in each programme’s annexes reveal that the availability of the funds will be tied to delivery of a series of milestones and objectives by member states. The documents also suggest that the use of the funds should be interpreted more as a supply-side policy underpinned by green and digital transition and economic resilience targets rather than as an exercise designed to stimulate a demand-fuelled recovery.

The European Recovery Plan can therefore be characterised more as a financial framework for member states’ supply-side policies (i.e., reforms) than a form of fiscal stimulus for urgent economic recovery, although the multiplier effect of the public investments contemplated on each country’s and the bloc’s GDP is undeniable. The simulations run by the European Commission (2020c) on the macroeconomic impact of a 750 billion euro recovery plan with 93.5% of the funds in the form of public investment point to an impact of between 2.8 and 4.2 percentage points of GDP between 2021 and 2024 for the group of highly-indebted countries, which includes Spain, alongside Italy, Portugal, Greece and Cyprus. The impact also depends on the Plan’s ability to mobilise private investment and assumes that all of the funds are invested during the first four years.

Programme timing, recommendations and assessment criteria

The deployment of the funds, which will be spread out over seven years, will be subject to delivery of certain objectives and a strict reform programme marked by precise implementation milestones. The evaluation and approval of the programmes, their monitoring, and the release of the funds as the milestones are met will fall within the remit of the European Commission and Council.

The recovery plans drawn up by each member state will be integrated into their respective national reform programmes, which are presented annually along with the updated stability programmes. The Commission and Council will then make their recommendations, which will be incorporated into the national plans. The documents that flesh out the Recovery Plan anticipate that the assessments of the national programmes will factor in their alignment with the priorities identified at the European level, particularly with respect to the twin green and digital transition, the long-lasting effects of the measures, their coherence and the ability to substantiate the sums requested in the form of reform and investment proposals.

Against that backdrop, on May 20th, 2020, the European Commission published the Council Recommendation on the 2020 National Reform Programme of Spain (European Commission, 2020d). This document refers to the Country Report on Spain published on February 26th, 2020 (European Commission, 2020e), as part of its assessment of the progress made on structural reforms as part of the so-called 2020 European Semester Framework for the coordination of economic policies across Europe. It is worth taking a look at the key points made in these documents insofar as they contain some of the criteria which in all likelihood will be used to analyse the programmes presented by Spain under the scope of the European Recovery Fund.

By way of example, some of the lines of initiative falling under the scope of the funds allocated to supporting member states’ recovery and resilience, which is the largest ‘pot’ of funds contemplated within the Plan (655 billion euros), condition the EU aid on the reform proposals contemplated in the European Semester and the twin green and digital transition objectives. By the time the Spanish government presents its draft budget for 2021 in Brussels, it will need to include the investment and reform programme for Spain with all the corresponding requirements and financing formulae.

As noted in the Communication from the Commission (2020a) COM(2020) 456 Final, the three political principles that should inspire the states’ reform strategies and long-term growth plans are the European Green Deal; digitalisation of the economy; and, a fair and inclusive recovery, all of which underpinned by an effort to build a more resilient European economy by focusing on strategic sectors and areas. Those principles are bound to shape the European authorities’ assessments of the national programmes presented in a bid to obtain the new European funds.

Recovery and resilience

The Council Recommendation on the 2020 National Reform Programme of Spain (European Commission, 2020d), issued on May 20th, 2020, outlines the lines of initiative that should be prioritised for access to the recovery funds: (i) the front-loading of public investment projects and the promotion of private investment in order to drive demand; and, (ii) support for companies in the sectors hardest hit by the crisis. Importantly, these investment initiatives must be strategically oriented. Although the Commission wants all EU countries to focus on these requirements, it is more pressing in its recommendations for Spain on account of its distance from European trends. Specifically, Spain must increase productivity and foster innovation, guided by the twin digital and green transition objectives.

In the context of the European Semester, the European Commission (2020e) has highlighted the scant growth in the productivity of the Spanish economy in recent years. In pinpointing some of the reasons for that shortfall, it warns of shortcomings in the field of innovation where Spain’s performance is below the EU average. In particular, it notes the slow digital uptake in the SME segment, the low number of ICT experts, and the drag implied by overly-high reliance on temporary contracts among employees, which exacerbates inequalities and labour poverty. Hence, its insistence on supporting the digitalisation of businesses, notably SMEs and micro-enterprises.

The European Union also underlines the need to reinforce research and innovation governance at all levels, specifically the importance of increasing cooperation between research centres and the business community, raising the share of students in science and digital technologies, and increasing the attractiveness of vocational education. In short, it calls on Spain to refocus the resources earmarked to the research effort and enhance education and skills training so as to drive productivity gains.

Cohesion and REACT-EU

The tremendous impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain has exposed, in the opinion of the Commission, existing structural shortcomings in health infrastructure, regional disparities in health spending, physical resources and staff, coordination issues between the different levels of government and the need to reinforce primary care and develop e-health. The core lines of initiative of the European Recovery Plan prioritise investment in the healthcare sector, which the Spanish authorities must address.

Regional cohesion also features in the agenda and observations formulated by the European Commission, which advocates for stronger cooperation between the different levels of government. This could be accomplished through projects aimed at reducing the digital divide between urban and rural areas, investing in rail for freight transport and ensuring equal access to digital learning for students in rural areas and from vulnerable households. Education therefore emerges as an area of strategic importance for any investment projects presented in Europe.

In the broadest sense, the promotion of inclusive growth entails lowering the incidence of poverty and social exclusion, reforming assistance and reinsertion programmes for the long-term unemployed, temporary workers and the self-employed, and reducing disparities in regional minimum income schemes.

Just Transition Fund

The transition towards a carbon-neutral and digitalised economy are two of the objectives which the European authorities have frequently cited as conditions for accessing the recovery funds. The European Recovery Plan explicitly contemplates the allocation of funds to projects aimed at a just transition and a specific regime under the aegis of the Invest EU programme.

Spain is one of the member states with greatest exposure to climate change and the Commission has flagged the importance of new measures designed to accelerate the transition in the areas of sustainable mobility, decarbonisation of energy and building energy efficiency.

The European Commission has issued a raft of recommendations along these lines. In the context of higher public and private investment, execution of those recommendations could be accelerated to boost the economic recovery and create new jobs. This would include investments in energy infrastructure, the reduction of energy consumption in private and public buildings, sustainable transport, the development of renewable energies, water and waste management, circular economic initiatives, etc.

Conclusion

The scale of the challenges facing the Spanish economy as a result of the COVID-19 crisis will require the entire arsenal of expansionary monetary and fiscal policy in order to repair the economic and social damage caused by the pandemic, facilitate the return to a stable growth path, and tackle the reforms needed to deliver the twin green and digital transition objectives. On the monetary front, the European Central Bank has expanded its asset repurchase programme twice and passed a package of exceptional measures that provide considerable relief to debt issuers in the eurozone countries with the highest risk premiums. Fiscal policy, however, remains part of national policy, which means that the health crisis has the potential to become an asymmetric shock which undermines the position of those countries with less firepower for reactivating their respective economies. This necessitates the deployment of the European financing programmes in order to mobilise funds that help the national productive sectors make the required adjustments, overcome the effects of the economic shutdown, resume a sustainable growth trajectory, and support job creation.

The European Union has responded faster and more forcefully than in previous crises due to the destructive and unprecedented impact of the pandemic. The Commission itself has acknowledged that the biggest spending programme in its entire history –the European Recovery Plan– needs to be cast in terms of a European public good with benefits that will extend to all of the member states’ economies irrespective of the amounts ultimately allocated to each.

Spain stands to receive grants equivalent to 5.8% of its GDP in 2019 and loans equivalent to up to 6.8% of its GNI.

However, the Plan suffers from three problems that seriously limit its capacity as an instrument for economic recovery. Firstly, its amount: 5.4% of EU-27 GDP does not seem to be a sufficient stimulus to tackle a crisis of this size. Second, its implementation schedule, too long to cope with the immediate needs to boost demand in the countries most affected by the pandemic. And third, its orientation, more concerned with medium-term reforms, than with ensuring the immediate reactivation of the economy. It would be advisable, therefore, to complete the Plan with other fiscal stimulus programs, with more immediate execution and aimed at mitigating the effects on the productive and social sectors hardest hit by the crisis.

The urgency of the situation therefore warrants making the most of the programmes already on offer by the European Union in 2020 via a package of measures approved in May: the SURE Instrument, the ESM credit line and the EIB guarantees.

While the European Recovery Plan is being negotiated, all levels of government should prepare to leverage the full potential of the Plan and articulate a roadmap for a sustainable economic recovery.

Notes

Note that the estimates for national fiscal support in response to the pandemic may vary relative to earlier estimates published by Funcas in other publications, as these figures are being constantly updated.

References

ANDERSON, J., BERGAMINI, E., BREKELMANS, S., CAMERON, A., DARVAS, Z., DOMÍNGUEZ JÍMENEZ, M. and MIDõES, C. (2020). The fiscal response to the economic fallout from the coronavirus. Bruegel Datasets, June 4th. Retrievable from: https://www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/covid-national-dataset/ESM. (2020a). Assessment of public debt sustainability and COVID-related financing needs of euro area Member States. Retrievable from:

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/annex_2_debt_sustainability.pdfEUROPEAN COMMISSION. (2020a). The EU budget powering the recovery plan for Europe. COM(2020) 442 final, May 27

th, 2020. Retrievable from:

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:4524c01c-a0e6-11ea-9d2d-01aa75ed71a1.0018.02/DOC_1&format=PDF— (2020b). Europe’s moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation. COM(2020) 456 final, May 27

th, 2020. Retrievable from:

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0456&from=ES— (2020c). Identifying Europe’s recovery needs, SWD(2020) 98 final, May 27

th, 2020. Retrievable from:

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/assessment_of_economic_and_investment_needs.pdf— (2020d). Council Recommendation on the 2020 National Reform Programme of Spain and delivering a Council opinion on the 2020 Stability Programme of Spain, COM(2020) 509 final, May 20

th, 2020. Retrievable from:

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/2020-european-semester-csr-comm-recommendation-spain_es.pdf — (2020e). Country Report Spain 2020. Commission Staff Working Document, European Semester 2020, SWD(2020) 508 final, February 26

th, 2020. Retrievable from:

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/2020-european_semester_country-report-spain_es.pdf EUROPEAN COUNCIL. (2020). Special Meeting of the European Council (17-21 July 2020). Conclusions.

GOVERNMENT OF SPAIN. (2020).

2020 Stability Programme Update. Kingdom of Spain. Retrievable from:

https://www.mineco.gob.es/stfls/mineco/comun/enlaces /destacados/20200430_PROGRAMA_ESTABILIDAD.pdfIMF. (2020).

Reopening from the Great Lockdown: Uneven and Uncertain Recovery, June. Retrievable from:

https://blogs.imf.org/2020/06/24/reopening-from-the-great-lockdown-uneven-and-uncertain-recovery/MEDE. (2020b).

Out of the box: a new ESM for a new crisis, June. Retrievable from:

https://www.esm.europa.eu/blog/out-box-new-esm-new-crisisOECD. (2020).

Economic Outlook, 107, Preliminary version, June. Retrievable from:

https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/0d1d1e2e-en.pdf?expires=1592811782&id=id&accname=guest &checksum=C30C32A1CFAB0388F2C8C1146B3EF9F0

Eduardo Bandrés. Funcas and University of Zaragoza

Lola Gadea. University of Zaragoza

Vicente Salas. University of Zaragoza

Yolanda Sauras. Economic and Social Council of Aragon